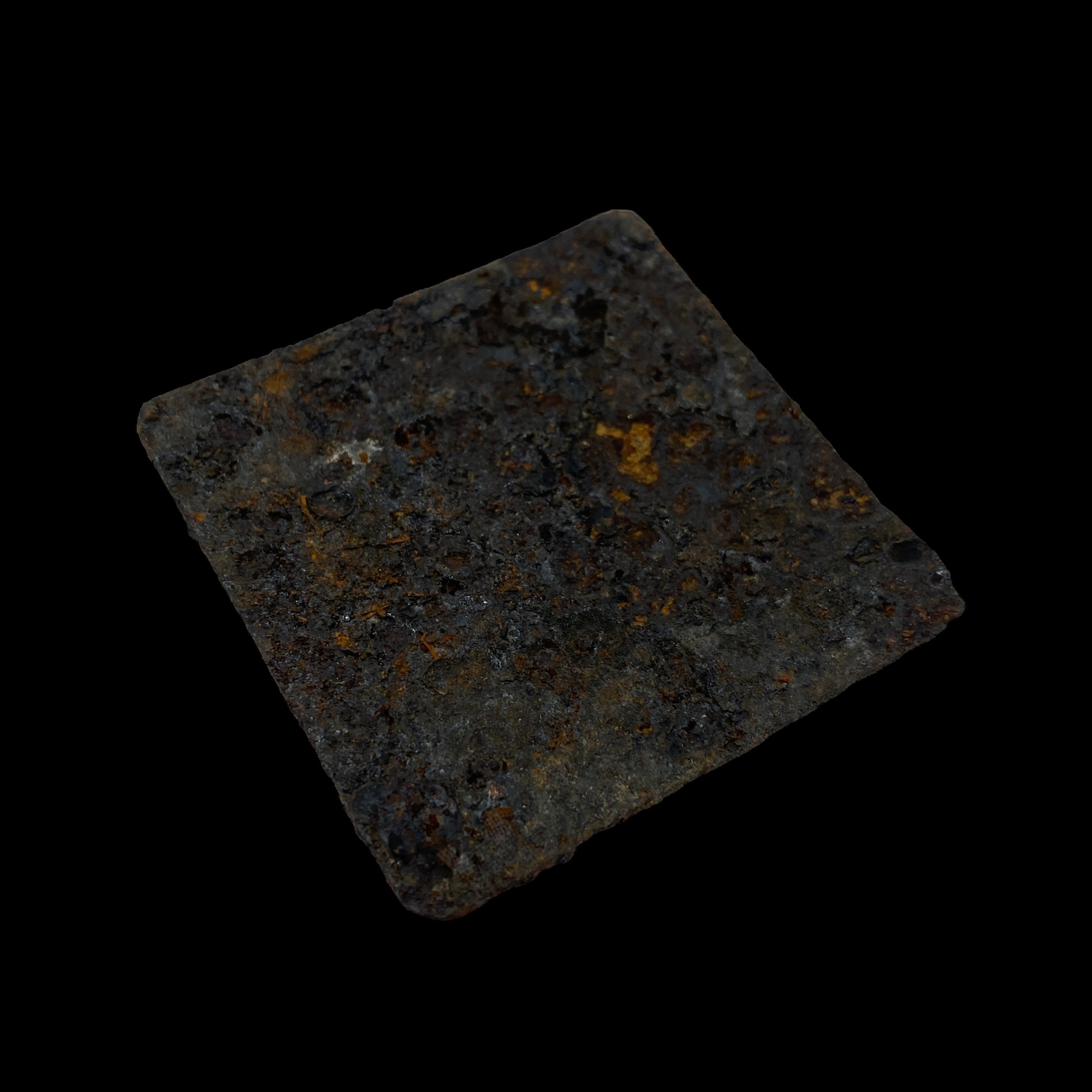

RARE! WWII 1944 D-Day U.S. Glider Pilots FLAK Jacket steel Platee Recovered Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy

RARE! WWII 1944 D-Day U.S. Glider Pilots FLAK Jacket steel Platee Recovered Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy

Comes with C.O.A.

This incredible and very historic WWII D-Day artifact is a U.S. glider pilots FLAK jacket steel plate that was recovered at Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy région, northwestern France.

During World War II, the United States developed and issued FLAK jackets to protect their soldiers from enemy shrapnel and bullets. These jackets were made of multiple layers of steel plated material and were highly effective in saving lives on the battlefield. One group of soldiers who benefited from these jackets were the glider pilots who participated in the D-Day landings near Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy.

*The FLAK jackets proved to be highly effective in protecting the glider pilots during the Normandy landings. Many pilots reported being hit by shrapnel or bullets, but were able to continue their missions thanks to the jackets. One pilot, Lieutenant Colonel Charles H. Young, credited his FLAK jacket with saving his life when his glider was hit by anti-aircraft fire during the landing at Sainte-Mère-Église.

Glider pilots played a crucial role in the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6th, 1944. They flew unarmed gliders, filled with troops and supplies, behind enemy lines in order to deliver reinforcements and equipment to the troops on the ground. The pilots were exposed to great danger during these missions, as they had to navigate through anti-aircraft fire and enemy fighters without the benefit of guns or armor.

To protect the glider pilots during the D-Day landings, the United States Army Air Forces issued them with FLAK jackets. These jackets were made of a combination of nylon, steel plates, and other materials designed to stop shrapnel and small-arms fire. They were relatively lightweight and easy to wear, which was important for pilots who needed to move around in cramped cockpits.

The use of FLAK jackets by glider pilots during the D-Day landings near Sainte-Mère-Église highlights the importance of protective gear in modern warfare. Without these jackets, many pilots would have been killed or seriously injured during the dangerous missions they undertook. The success of the FLAK jackets in this context also demonstrates the importance of continuous innovation and improvement in military technology, as the United States was able to develop and issue effective protective gear to its soldiers during a critical moment in the war.

In conclusion, the use of FLAK jackets by glider pilots during the D-Day landings near Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy was a critical factor in the success of the Allied invasion. These jackets saved many lives and allowed the pilots to complete their missions despite the danger they faced. The development and deployment of these jackets is a testament to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the United States military during World War II.

Sainte Mere Eglise was a strategic crossroads town situated along the N13, the road that led to Utah and Omaha beaches which if assaulted and captured from German troops would provide a vital exit road for the landing troops from Utah Beach.

In total now 432 Dakota planes of the 101st were heading toward the Cotentin Peninsula. Roughly ten minutes after the 101st, the men of the 82nd Airborne Division were to board another 377 planes (some sources give 369, not to mention 52 gliders with heavy equipment) for takeoff from five airfields in Lincolnshire.

At the same hour as the men of the 505th 3rd Battalion were securing the streets of Sainte-Mère-Église from the Germans and were to raise the Stars and Stripes above the town, a few dozen of mostly wooden gliders of the 82nd Division were descending toward the dropping zone ‘O’ Apr. at 4:00-4:10 a.m. June 6. ‘Operation Detroit’ was the second of the three successive airborne assaults after ‘Operation Boston’ itself and the latter ‘Elmira’ (further delivering of the soldiers and heavy equipment). ‘Operation Detroit’ was aimed to supply the paratroopers (who had landed at the night) with ammunition, radio equipment, and light vehicles such as jeeps, machine guns, and artillery pieces. The 52 C-47 with the gliders (each plane carried one) did depart from England at 1:20 and had to fly the same route as the paratroopers before them, facing the same fierce anti-aircraft fire from the ground. In total, 16 guns (of 57mm caliber) of the 80th Airborne Anti Aircraft Battalion along with 220 men, 22 jeeps as light vehicles, and more than ten tonnes of ammunition and equipment for the paratroopers were now on the planes. Despite clouds and the German anti-aircraft fire from the ground, twenty-three gliders managed to touch the ground actually within dropping zone ‘O’ and 9 others touched the ground in a 3km radius. The majority of them suffered damages, including the fact that at least half of the equipment was now out of order. Six or seven of the 16 guns were put into action by noon on June 6. Three soldiers lost their lives during the landing and another few dozen (some estimated 23 figures) were wounded.

The Mission:

Mission Boston was assigned to the 82nd US Airborne Division and the capture of Sainte Mere Eglise to the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Their other objective was to seize the eastern ends of the bridges spanning the Merderet River at Chef-du-Pont and La Fière. These were the only two bridges that could sustain the crossing of the river with armor. The drops of the 82nd Division were scheduled five hours before the landings. Mission Albany would precede Mission Boston by one hour. The paratroopers of the US 101st Airborne were to destroy the batteries in Saint-Martin-de-Varreville and Mésières, capture the Douve River’s lock at La Barquette, two footbridges spanning the river at La Porte and the bridges that spanned it at Sainte-Come-du-Mont. Finally, they were to capture the causeways that linked Utah to the inland to allow the landing troops exit the beach.

The disastrous drops:

In the early hours of June 6 (between 00.50am and 1.40am) the pathfinders were dropped behind the enemy lines in order to prepare the drop zones. At 1.40am the men of the 82nd U.S. Airborne Division were dropped off over the Merderet River and marsh. The poor weather conditions – low cloud on the northern part of the Cotentin Peninsula and ground fog over the drop zones – altered the visibility of the marker flares installed by the pathfinders. Heavy German anti-aircraft fire added to the situation. As a result, the drops of both the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were scattered over an area four times larger than the scheduled one. Indeed, the aircraft carrying the paratroopers found themselves under severe anti-aircraft enemy fire, as soon as they approached the coasts. The 505th was the only Regiment to be dropped almost accurately to the northwest of Sainte Mere Eglise! Many paratroopers from the 101st Airborne touched ground near Sainte Mere Eglise, far west from their planned drop zone.

Sainte Mere Eglise – 1.00am to 4.30am:

At 1.00am the constant enemy shelling – or maybe one of the marker flares dropped by the pathfinders – triggered a fire in one of the houses situated by the church in Sainte Mere Eglise. This obviously raised the alarm among the inhabitants and the Germans positioned in the village. Soon the fire wreaked havoc upon the town. Tragically, it also lightened up the sky and allowed the Germans to locate the paratroopers of the 2nd Battalion of the 505th PIR, as they were coming down. Numbers of paratroopers were therefore riddled with bullets before reaching the ground. Others landed on trees or utility poles and were killed before they could even undo their parachutes. Tragically others landed straight into the inferno. They were eventually rescued by 158 paratroopers of the 3rd Battalion of the 505th Parachutist Infantry Regiment and elements from the 101st Airborne, all placed under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Krause. The men encircled Sainte Mere Eglise and seized the village at 4.30am, making about 30 prisoners. Sainte Mere Eglise became known to the world after the film The Longest Day because of the paratrooper John Steele of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Steele indeed landed on the church’s steeple and pretended to be dead to avoid being shot by the Germans. He stayed put, hanging in the air, for two long hours and watched helplessly as the Germans shot his comrades around him. The Germans, however, took him as a prisoner, but not for long. Steele managed indeed to escape and joined his Division when it entered the village at 4.30am. A German counterattack was neutralised on June 7. Sainte Mere Eglise is proud to be one of the first Norman towns liberated on D-Day.