*(SOLD)* VERY RARE! (MINT CONDITION) 1944 1st Edition D-Day Operation Neptune BIGOT Map Omaha Beach WEST (Vierville-sur-Mer)

*(SOLD)* VERY RARE! (MINT CONDITION) 1944 1st Edition D-Day Operation Neptune BIGOT Map Omaha Beach WEST (Vierville-sur-Mer)

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

Titled “Titled “OMAHA BEACH-WEST (Vierville-sur-Mer)” this original, ultra rare, and museum-grade TOP-SECRET “BIGOT” D-Day amphibious beach chart vividly illustrates the intensive planning and operational accuracy that was behind Operation Neptune, the largest amphibious seaborne invasion in history. Prepared by the Commander Task Force 122, April 21, 1944 this near mint condition and double sided WWII Omaha Beach BIGOT map is a rare 1st edition BIGOT map…meaning it was one of the first D-Day maps produced by the BIGOT department that showed an incredibly large section of the Omaha Beach and the now designated landing craft areas. It includes all of the landing craft specified/designated landing areas from Vierville sur-Mer to le-Haut Chemin including: DOG RED, DOG WHITE, DOG GREEN, & CHARLIE. Many thousands of lives depended upon the success of the operation – millions in fact, it was thus vital that this map contained as much information possible of this Normandy coastal section to insure the most military success for the Allied Powers.

Paratroopers dropped in behind enemy lines an hour or so after midnight. Infantry and tanks hit the beaches at dawn. On Utah Beach, the men rapidly overwhelmed the surprised defenders, suffering roughly 170 casualties. The scene at Omaha Beach was dramatically different. Some 24 miles away, the troops there endured withering fire from a determined German defense, leaving some 2,000 men as casualties. Airborne troops suffered the worst, with 2,499 casualties. In all, more than 4,400 Allied troops were killed on D-Day.

DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT THE CREATION OF THIS 1944 WWII D-DAY BIGOT MAP:

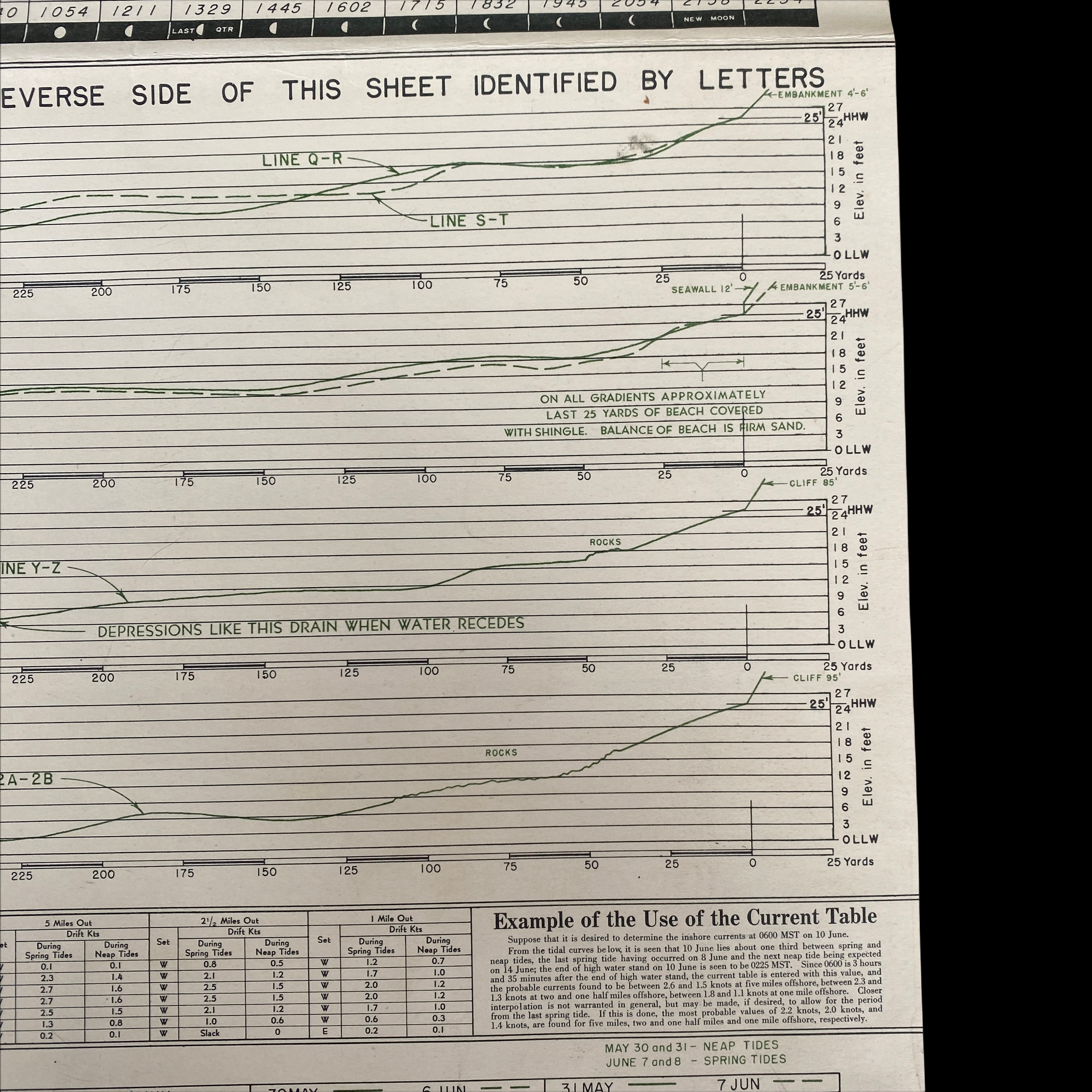

The BIGOT map is an extremely detailed topographical map, with roads and built-up areas in black, green indicating different types of vegetation; and brown indicating elevations and topographical features, including the steep bluffs overlooking the beach. A variety of dashed lines in the water indicate depths at low (brown) and high (blue) tides.

Below each map is a profile view of the coastline to facilitate navigation by the landing craft, with the practical note “Building landmarks, especially near the beach, may be destroyed before any craft land. Terrain features, therefore, are much more reliable for visual navigation.” These photos would have been taken from midget submarines with a crew of two, and sometimes four men, at great risk to their lives. These British sailors were among the relatively unknown heroes of D-day.

Below the title brief note hints at the complex, multi-layered information-gathering effort that yielded the BIGOT maps. The BIGOT maps were the product of a multilayered TOP SECRET effort: Starting with existing base maps and hydrographic data, largely supplied by the British Hydrographic Office, military cartographers and artists added data from aerial reconnaissance surveys by Allied warplanes, including extraordinarily dangerous low-level overflights. To these were added information from a host of other sources, including reconnaissance of the beaches by commandos (“frogmen”) and reports from French Resistance fighters.

The reverse side of each BIGOT map had detailed hourly currents, beach gradients, and tidal stages.

“BIGOT” CLASSIFICATION:

“Top Secret – Bigot” was the Allies’ highest level of secrecy during WWII. The Bigot List was a list of a very exclusive group of named individuals who were the only persons allowed to know both the proposed sites and dates of the D-Day Landings. Because of the danger of capture by the Germans the only person on the Bigot List allowed to go outside mainland Britain is believed to be Winston Churchill and as a safeguard his personal bodyguard was instructed to shoot the Prime Minister if there was any danger of him falling into enemy hands. BIGOT was a World War II security classification at the highest level of security - above Top Secret.; BIGOT stood for the British Invasion of German Occupied Territory, was chosen by Churchill before America came into the War and remained the security classification even when Eisenhower took over the planning role.

In “Untold Stories of D-Day” in the June 2002 issue of National Geographic Magazine, Thomas B. Allen wrote about the Neptune Bigot maps: “One simple word, BIGOT, is stamped in big letters across the Operation Neptune Initial Joint Plan of February 12, 1944, and from then until June 6, that stamp appeared on all supremely secret pieces of paper handled by D-Day planners. If any of those papers or maps had fallen into enemy hands, the invasion would have failed or been scuttled… BIGOT was a code word within a code word, a security classification beyond Top Secret. When planners adopted Neptune as the code word for the naval and amphibious aspects of the invasion, they realized that greater protection had to be given to any document or map that even hinted at the time and place of D-Day. They chose the odd code word BIGOT by reversing the letters of two words—To Gib—that had been stamped on the papers of officers going to Gibraltar for the invasion of North Africa in November 1942. Those who were to get date-and-place information were given special security background checks. If they qualified, they were described as ‘Bigoted…

The BIGOT maps and documents were created in isolated cocoons of secrecy. One was hidden in Selfridges department store in London. BIGOT workers entered and left Selfridges by the back door, many of them knowing only that they were delivering scraps of information that somehow contributed to the war effort. Others with BIGOT clearances worked on Allied staffs scattered around London and southern England. So restricted was the BIGOT project that when King George visited a command ship and asked what was beyond a curtained compartment, he was politely turned away because, as a sentinel officer later said, ‘Nobody told me he was a Bigot.’

But nothing was more secret—or more vital to Operation Neptune—than the mosaic of Allied intelligence reports that cartographers and artists transformed into the multihued and multilayered BIGOT maps. On them were portrayed details of Hitler’s vaunted Atlantic Wall, a network of coastal defenses, designed to repel invaders. To discover what the Allied invaders faced, American, British, and French operatives risked their lives—and sometimes gave their lives—in the process of filling in the BIGOT maps. Revelations about Normandy’s undulating seafloor came from frogmen who also got sand samples on beaches patrolled by German sentries. Such BIGOT map notations as ‘antitank ditch around strongpoint’ or ‘hedgehogs 30 to 35 feet (9 to 10 meters) apart’ were often the gifts of French patriots.” Notations in red on the map here offered to include: “Probably Mined” and three areas marked “Drainage Ditch.” Allen writes that “French laborers conscripted by the Nazis paced distances between obstacles or kept track of German troop movements… BIGOT maps began with information gleaned from old scenic postcards of the Normandy coast and charts from the Napoleonic era. Next came the special deliveries from the French Resistance. Then in mid-May 1944, BIGOT mapmakers asked for low-level aerial photos of the coast. Pilots trained to fly at 10,000 feet, called this wave-top flying ‘diving’ because they felt that in their unarmed and unarmored aircraft they were rolling the dice with death.

H-Hour 0630

Lead Allied assault forces

1st US Infantry Division, troops from 29th US Infantry Division, US Rangers

German Defenders

Troops from 352nd Infantry Division and 716th Infantry Division

Objectives

US forces aim to advance inland and gain control of the main east-west road. Further to the west, US Rangers land at Pointe du Hoc with the mission of scaling steep cliffs and disabling the large German guns situated on top of them, which could otherwise fire at Allied ships.

Hourly Timeline of D-Day Landing on Omaha Beach:

0300

Landing ships miles offshore begin lowering the landing craft that will take the assault infantry to the beach. Many troops have to climb down cargo nets from the ships into the landing craft.

0335

Bomber aircraft of RAF Bomber Command attack a range of targets in the whole landing area.

0455

The first waves of landing craft head for the beach.

0550

USS Nevada bombarding a German gun battery in Normandy with her 14 inch guns. (Photo: Conseil Régional de Basse-Normandie / US National Archives)

Allied warships begin bombarding German defenses in the Omaha area. Some German gun batteries try to fire back but are temporarily silenced.

0550

Despite the rough seas, most of the 64 DD (amphibious) tanks begin to launch into the water around 5,000 yards out. Many sink as they approach the beaches, meaning that the infantry will have fewer tanks to support them as they land.

0556

Nearly 450 American heavy bomber aircraft drop bombs, but they fall too far inland (5km) rather than in the beach area. Due to low cloud, the aircraft add a brief delay to dropping their bombs, to ensure they do not hit any friendly forces.

0600

Support landing craft begin to fire guns and rockets against German defences along the beach.

0630

US infantry begins landing on Omaha Beach. They have to cross around 300 yards of beach before they can find a little cover in the form of a shingle bank and sea wall. Many are killed by the fire of German defenders, or lose their weapons and equipment in the confusion.

0700 – 0800

Enemy fire and a higher than expected tide make it difficult for the Americans to clear away beach obstacles, which are increasingly covered by the tide. Many of the larger landing craft have to wait offshore rather than landing their troops because they cannot get through the obstacles.

0710

2nd US Rangers arrive at Pointe du Hoc, and begin climbing the cliffs so they can attack the coastal gun battery on top.

0745

2nd US Rangers have scaled the cliff. They find that the coastal guns have been removed, but later find them inland and destroy them.

0800 – 0900

US troops are still struggling to gain a foothold in the main beach landings. Eleven destroyers come closer inshore to fire their guns directly at German strongpoints to aid the troops. Gradually small groups of US infantry begin to advance off the beach, where there are weaker spots in the German defences.

1100 – 1200

US troops start to get to the top of the bluffs (hills at the back of the beach). However many are still disorganised. Surviving German troops in the beach defences start to surrender (though some hold out until late afternoon).

1300

The road inland at St Laurent is clear, so that vehicles can move up it and support the infantry.

2000

During the afternoon, engineers have managed to clear more routes through the beach obstacles and more routes off the beaches that vehicles can use. US troops capture several villages just behind the beach.

2400

Omaha Beach: At the end of D-Day: Due to the difficulties experienced by US troops at the start of the landings, the Americans have only advanced about one mile inland in most places. The beachhead is not yet secure and is still shelled by German artillery. However German forces here are also off balance, and not yet able to make a strong counter-attack. At Pointe du Hoc, 2nd US Rangers have destroyed the long range coastal guns and held out against strong counter-attacks, losing 90 out of the 225 men who had originally landed. Troops from the main beach landings have not yet linked up with them.

2400

Casualties at Omaha Beach on D-Day: Total casualty figures for D-Day were not recorded at the time and are difficult to confirm in full. The US Army has lost 3,686 casualties including around 777 killed. Other Allied losses include 539 naval and 10 air forces casualties. The German have lost over 1,000 casualties.

General Summary of D-Day Operations on Omaha Beach:

On the morning of June 6, 1944, two U.S. infantry divisions, the 1st and the 29th, landed at Omaha Beach, the second to the west of the five landing beaches of D-Day. Opposing the landings was the German 352nd Infantry Division. Of its 12,020 men, 6,800 were experienced combat troops, detailed to defend a 53-kilometer (33 mi) front. The German strategy was based on defeating any seaborne assault at the water line, and the defenses were mainly deployed in strongpoints along the coast. Casualties on Omaha Beach were the worst of any of the invasion beaches on D-Day, with 2,400 casualties suffered by U.S. forces. And that includes wounded and killed as well as missing. There is no concrete number for the German forces that were killed at Omaha Beach. Those records simply did not exist, and entire German units were wiped out virtually to a man. Any best estimate at the German losses on D-Day is a guess.

D-Day and Omaha Beach:

Omaha Beach linked the U.S. and British beaches. It was a critical link between the Cotentin Peninsula, also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, and the flat plain in front of Caen. Omaha was also the most restricted and heavily defended beach. For that reason, at least one veteran U.S. Division (lst Infantry Division) was tasked to land there. The terrain was difficult. Omaha beach was unlike any of the other assault beaches in Normandy. Its crescent curve and unusual assortment of bluffs, cliffs and draws were immediately recognizable from the sea. It was the most defensible beach chosen for D-Day; in fact, many planners did not believe it a likely place for a major landing. The high ground commanded all approaches to the beach from the sea and tidal flats. Moreover, any advance made by U.S. troops from the beach would be limited to narrow passages between the bluffs. Advances directly up the steep bluffs were difficult in the extreme.

German strongpoints were arranged to command all the approaches and pillboxes were cited in the draws to fire east and west, thereby enfilading troops while remaining concealed from bombarding warships. These pillboxes had to be taken out by direct assault. Compounding this problem was the allied intelligence failure to identify a nearly full-strength infantry division, the 352nd, directly behind the beach. It was believed to be no further forward than St. Lo and Caumont, 20 miles inland. The V Corps was assigned to this sector. The objective was to obtain a lodgment area between Port-en-Bessin and the Vire River and ultimately push forward to St. Lo and Caumont in order to cut German communications (St. Lo was a major road junction). Allocated to the task were 1st and 29th Divisions, supported by the 5th Ranger Battalion and 5th Engineer Special Brigade.