*(SOLD)* VERY RARE 1944 1st Edition D-Day Operation Neptune BIGOT Map Utah Beach NORTH (Ravenoville)

*(SOLD)* VERY RARE 1944 1st Edition D-Day Operation Neptune BIGOT Map Utah Beach NORTH (Ravenoville)

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

Titled “Titled “UTAH BEACH-NORTH (Ravenoville)” this original, ultra rare, and museum-grade TOP-SECRET “BIGOT” D-Day amphibious beach chart vividly illustrates the intensive planning and operational accuracy that was behind Operation Neptune, the largest amphibious seaborne invasion in history. Prepared by the Commander Task Force 122, April 21, 1944 this near mint condition and double sided WWII Utah Beach BIGOT map is a rare 1st edition BIGOT map…meaning it was one of the first D-Day maps produced by the BIGOT department that showed an incredibly large section of the Utah Beach and the designated landing craft areas. Many thousands of lives depended upon the success of the operation – millions in fact, it was thus vital that this map contained as much information possible of this Normandy coastal section to insure the most military success for the Allied Powers.

Utah, the westernmost of the five landing beaches, is on the Cotentin Peninsula, west of the mouths of the Douve and Vire rivers. The terrain between Utah and the neighboring Omaha was swampy and difficult to cross, which meant that the troops landing at Utah would be isolated. The Germans had flooded the farmland behind Utah, restricting travel off the beach to a few narrow causeways. To help secure the terrain inland of the landing zone, rapidly seal off the Cotentin Peninsula, and prevent the Germans from reinforcing the port at Cherbourg, two airborne divisions were assigned to airdrop into German territory in the early hours of the invasion.

DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT THE CREATION OF THIS 1944 WWII D-DAY BIGOT MAP:

The BIGOT map is an extremely detailed topographical map, with roads and built-up areas in black, green indicating different types of vegetation; and brown indicating elevations and topographical features, including the steep bluffs overlooking the beach. A variety of dashed lines in the water indicate depths at low (brown) and high (blue) tides.

Below each map is a profile view of the coastline to facilitate navigation by the landing craft, with the practical note “Building landmarks, especially near the beach, may be destroyed before any craft land. Terrain features, therefore, are much more reliable for visual navigation.” These photos would have been taken from midget submarines with a crew of two, and sometimes four men, at great risk to their lives. These British sailors were among the relatively unknown heroes of D-day.

Below the title brief note hints at the complex, multi-layered information-gathering effort that yielded the BIGOT maps. The BIGOT maps were the product of a multilayered TOP SECRET effort: Starting with existing base maps and hydrographic data, largely supplied by the British Hydrographic Office, military cartographers and artists added data from aerial reconnaissance surveys by Allied warplanes, including extraordinarily dangerous low-level overflights. To these were added information from a host of other sources, including reconnaissance of the beaches by commandos (“frogmen”) and reports from French Resistance fighters.

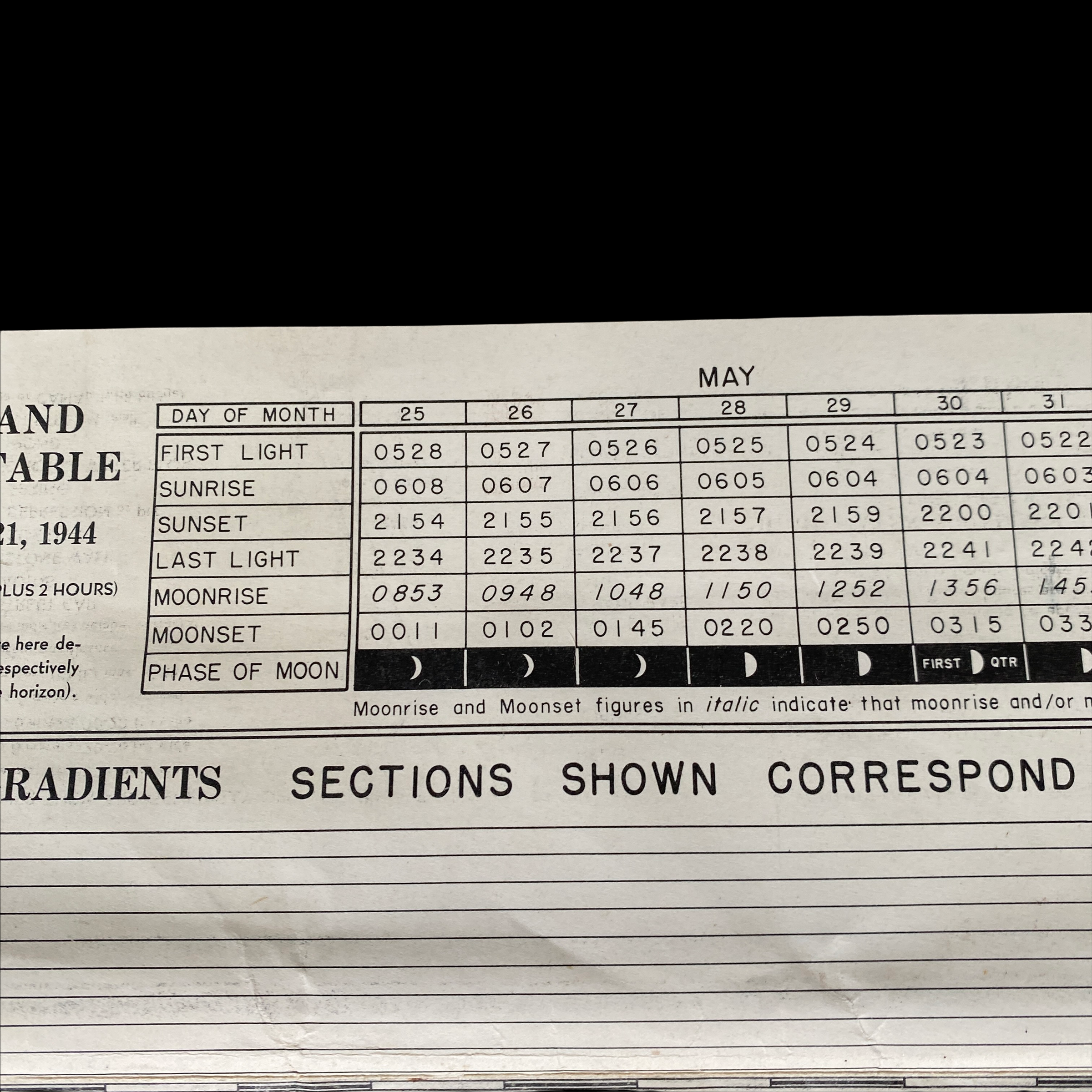

The reverse side of each BIGOT map had detailed hourly currents, beach gradients, and tidal stages.

“BIGOT” CLASSIFICATION:

“Top Secret – Bigot” was the Allies’ highest level of secrecy during WWII. The Bigot List was a list of a very exclusive group of named individuals who were the only persons allowed to know both the proposed sites and dates of the D-Day Landings. Because of the danger of capture by the Germans the only person on the Bigot List allowed to go outside mainland Britain is believed to be Winston Churchill and as a safeguard his personal bodyguard was instructed to shoot the Prime Minister if there was any danger of him falling into enemy hands. BIGOT was a World War II security classification at the highest level of security - above Top Secret.; BIGOT stood for the British Invasion of German Occupied Territory, was chosen by Churchill before America came into the War and remained the security classification even when Eisenhower took over the planning role.

In “Untold Stories of D-Day” in the June 2002 issue of National Geographic Magazine, Thomas B. Allen wrote about the Neptune Bigot maps: “One simple word, BIGOT, is stamped in big letters across the Operation Neptune Initial Joint Plan of February 12, 1944, and from then until June 6, that stamp appeared on all supremely secret pieces of paper handled by D-Day planners. If any of those papers or maps had fallen into enemy hands, the invasion would have failed or been scuttled… BIGOT was a code word within a code word, a security classification beyond Top Secret. When planners adopted Neptune as the code word for the naval and amphibious aspects of the invasion, they realized that greater protection had to be given to any document or map that even hinted at the time and place of D-Day. They chose the odd code word BIGOT by reversing the letters of two words—To Gib—that had been stamped on the papers of officers going to Gibraltar for the invasion of North Africa in November 1942. Those who were to get date-and-place information were given special security background checks. If they qualified, they were described as ‘Bigoted…

The BIGOT maps and documents were created in isolated cocoons of secrecy. One was hidden in Selfridges department store in London. BIGOT workers entered and left Selfridges by the back door, many of them knowing only that they were delivering scraps of information that somehow contributed to the war effort. Others with BIGOT clearances worked on Allied staffs scattered around London and southern England. So restricted was the BIGOT project that when King George visited a command ship and asked what was beyond a curtained compartment, he was politely turned away because, as a sentinel officer later said, ‘Nobody told me he was a Bigot.’

But nothing was more secret—or more vital to Operation Neptune—than the mosaic of Allied intelligence reports that cartographers and artists transformed into the multihued and multilayered BIGOT maps. On them were portrayed details of Hitler’s vaunted Atlantic Wall, a network of coastal defenses, designed to repel invaders. To discover what the Allied invaders faced, American, British, and French operatives risked their lives—and sometimes gave their lives—in the process of filling in the BIGOT maps. Revelations about Normandy’s undulating seafloor came from frogmen who also got sand samples on beaches patrolled by German sentries. Such BIGOT map notations as ‘antitank ditch around strongpoint’ or ‘hedgehogs 30 to 35 feet (9 to 10 meters) apart’ were often the gifts of French patriots.” Notations in red on the map here offered to include: “Probably Mined” and three areas marked “Drainage Ditch.” Allen writes that “French laborers conscripted by the Nazis paced distances between obstacles or kept track of German troop movements… BIGOT maps began with information gleaned from old scenic postcards of the Normandy coast and charts from the Napoleonic era. Next came the special deliveries from the French Resistance. Then in mid-May 1944, BIGOT mapmakers asked for low-level aerial photos of the coast. Pilots trained to fly at 10,000 feet, called this wave-top flying ‘diving’ because they felt that in their unarmed and unarmored aircraft they were rolling the dice with death.

D-Day and Utah Beach:

Airborne landings begin 0015

H-Hour, beach landings 0630

Lead Allied assault forces:

Airborne landings: 82nd & 101st US Airborne Divisions

Beach landings: 4th US Infantry Division

German defenders:

Troops from 709th Infantry Division, 91st Airlanding Division and 6th Parachute Regiment

Objectives:

Only four causeways lead away from the beach through an area that has been flooded by the German defenders. The US Airborne forces land early in the morning to take control of the inland ends of these causeways, as well as other key roads and bridges. They then have to hold these objectives until troops from the beach landings can reach them.

Hourly Timeline of D-Day Landing on Utah Beach:

0015

The first airborne pathfinders (101st US Airborne Division) land by parachute and quickly set up beacons to guide in the main body of airborne troops.

0019

The main body of 101st US Airborne Division begins landing by parachute and glider several miles behind the beaches. Many of the airborne troops are widely scattered and will take hours to re-group. Some paratroopers drop into flooded areas and drown.

0200

The main force of 82nd US Airborne Division begins landing. Some land in and around the town of Sainte Mère Église, a key objective.

0335

Heavy bombers of RAF Bomber Command attack German coastal gun batteries near Utah Beach. Their aim is to disable these batteries so they cannot fire on US troops who will land on the beaches in a few hours' time.

0405

Landing ships miles offshore begin lowering the landing craft that will take the assault infantry to the beach. Many troops have to climb down cargo nets from the ships into the landing craft.

0435

First waves of landing craft head for the beach.

0536

Allied warships begin firing their guns against the German defences. There are exchanges of fire between several warships and German coastal guns.

0600

Support landing craft begin firing guns and rockets against German defences along the beach.

0630

The first US troops (8th Regimental Combat Team) come ashore on schedule, but land at least 1,500 yards to the south of the intended sector. Fortunately this area is more lightly defended than their original objective. Shortly afterwards, most DD (swimming) tanks land successfully, though later than originally planned.

0800

Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt orders in follow-up troops. He decides to continue at the new landing site rather than reverting to the original one. US engineers are clearing beach obstacles so that follow-up landing craft can get to the beach in more safety.

0900 – 1000

US troops begin moving off the beach, along two of the four causeways. Meanwhile further inland, German forces fiercely counter-attack the positions held by US airborne troops.

1100 – 1200

As US troops advance further inland there is still some German resistance and artillery fire. Some Americans wade through flooded areas in order to reach their objectives. US troops advancing off the beach link-up with 101st US Airborne Division.

2100 – 2300

The final US airborne troops arrive by glider to reinforce 82nd Airborne Division.

2400

Utah Beach: At the end of D-Day: After being scattered during their landings, only 2,500 out of 6,600 US airborne troops have so far regrouped. Troops who landed on the beach have reached 101st US Airborne Division, but have not yet fully linked up with 82nd US Airborne Division who landed further to the west.

2400

Casualties at Utah Beach on D-Day: Total casualty figures for D-Day were not recorded at the time and are difficult to confirm in full. In the airborne landings 2,499 men became casualties, including 238 killed. Of the troops landing on the beaches, 589 were casualties including 197 who died. At Utah Beach there were also 235 naval and 340 air forces casualties. German losses here are unknown.

Forces involved:

There are two sectors on Utah: Uncle Red and Tare Green, located between the towns of Les Dunes-de-Varreville (North) and La Madeleine (South). These beaches are defended by the 709th german infantry division which has installed seven strongpoints. Two coastal artillery batteries, located at Montebourg and Saint-Marcouf, can open fire on this beach, since these guns have a firing range of almost 30 kilometers. The 7th U.S. Army of Major General J. Lawton Collins will be engaged first. It is composed of the 8th, 22nd and 12nd infantry regiments of the 4th american infantry division led by Major General Raymond O. Barton. These units will launch the attack of Utah Beach on D-Day in order to capture the landing beach sectors, then to establish a solid beachhead and to carry out the junction with the airborne troops of the 82nd and 101st American airborne divisions.

The assault must take place early in the morning at 6.30, a timetable that corresponds to the lowest tide. The Allies voluntarily choose this moment because the defenses of beaches installed by the Germans are clearly visible at low tide. Thus, the engineers can clear breaches on the beach in order to disembark the reinforcements.

The assault:

Tuesday June 6, at 3 o’clock in the morning, the U fleet (Utah) arrives near the Cotentin beaches and damps at approximately 18 kilometers off the coast, a distance which limits the effectiveness of the German coastal batteries. The sunrise comes at 05:58 a.m. exactly, 28 minutes after the beginning of the bombardment of the German positions by the allied warships. This huge bombardment follows air raids carried out by thousand of allied bombers.

American soldiers of the 1st and 2nd Battalions (8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division) who have embarked into the landing crafts are witnessing these bombardments which plow the French soil and fill the sky with immense plumes of smoke. Even though many of them suffer from a terrible seasickness, they are relieved to see their objectives under such a rain of steel. Two squadrons of amphibious “duplex drive” tanks are launched three kilometers from the shore and have to reach the beach areas by their own means thanks to two propellers and a rubber skirt. They progress in two waves of assault: the first one is composed of twelve “duplex drive” tanks and the second one is composed of sixteen identical tanks).

But the amphibious tanks are falling behind and are soon overtaken by the landing craft of the 2nd Battalion which take the lead of the offensive on the beach area nicknamed “Uncle Red”.

The 2nd Battalion lands on “Uncle Red” sector south-east of Saint-Martin-de-Varreville. The 1st Battalion lands fifteen minutes later on “Tare Green” beach area, east of Saint-Martin-de-Varreville, simultaneously with the amphibious tanks belonging to the 70th Tank Battalion (squadrons A and B). The latter reach the beach and immediately engage the opposing positions.

During the first minutes of the 4th Infantry Division’s landing on Utah Beach, the German shots are numerous but not very precise. Gradually, German machine guns leave room for random but deadly explosions of shells fired by field guns belonging to the German 709. Infantry Division.

These guns open fire from positions a few kilometers west of the landing beach (notably near Brécourt manor) and are camouflaged so that the Allied aircraft patrolling the Norman sky do not spot them.

Very quickly, the beach is under control. The tide is low and discovers the beach defenses over a distance of nearly 300 meters between the dunes and the sea. The fifth assault wavelands half an hour after H Hour. At 7:30 am, engineers open gaps through the beach obstacles allowing the landing crafts to approach without a hitch.