1943 ‘RESTRICTED’ Marshall Islands Campaign Pilot's Waterproof Survival Bail Out Map (Kwajalein Jaluit, Makin) - Lt. Moore - U.S.S. Enterprise (CV-6) Air Group

1943 ‘RESTRICTED’ Marshall Islands Campaign Pilot's Waterproof Survival Bail Out Map (Kwajalein Jaluit, Makin) - Lt. Moore - U.S.S. Enterprise (CV-6) Air Group

Size: 8 x 8 inches

Letter of Authenticity included.

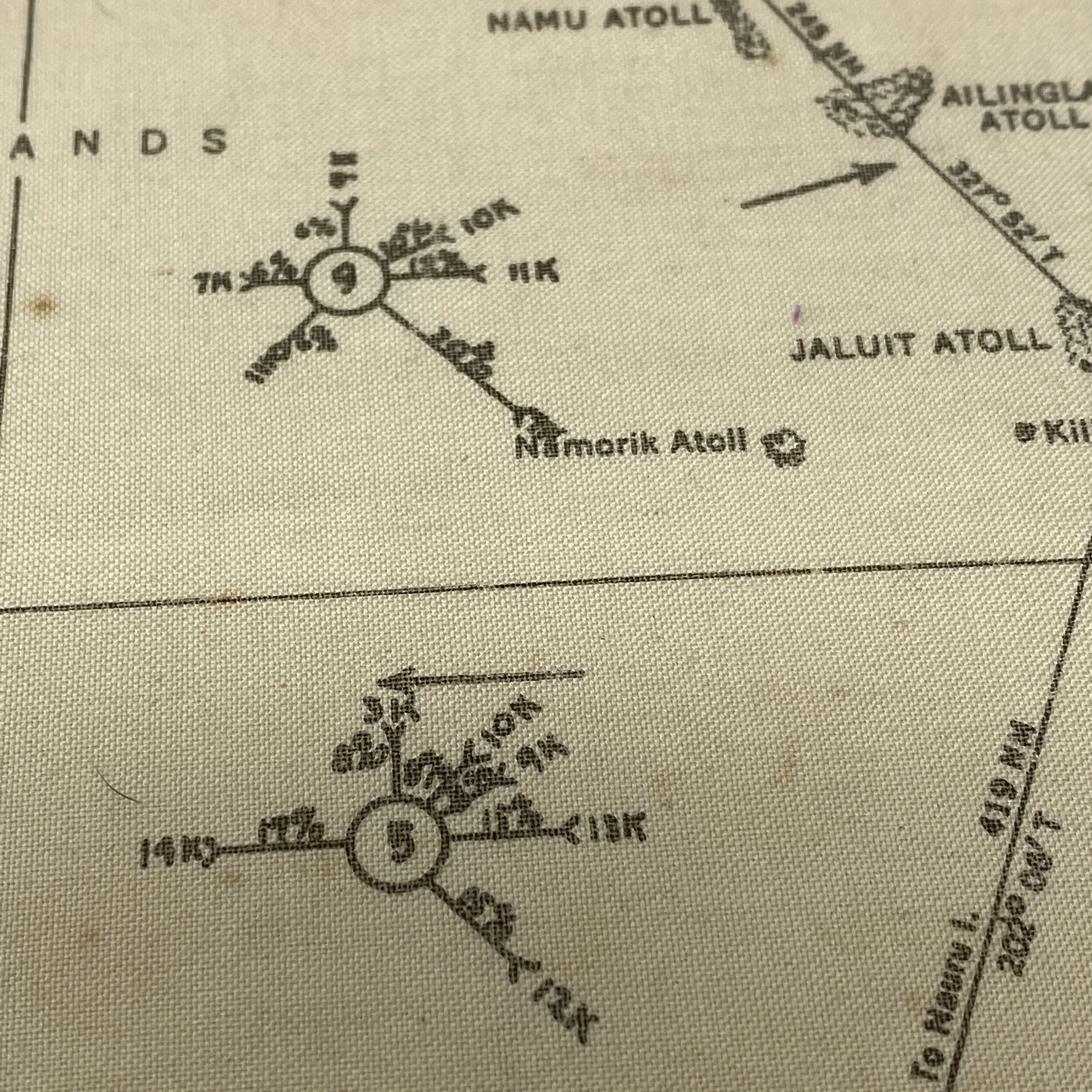

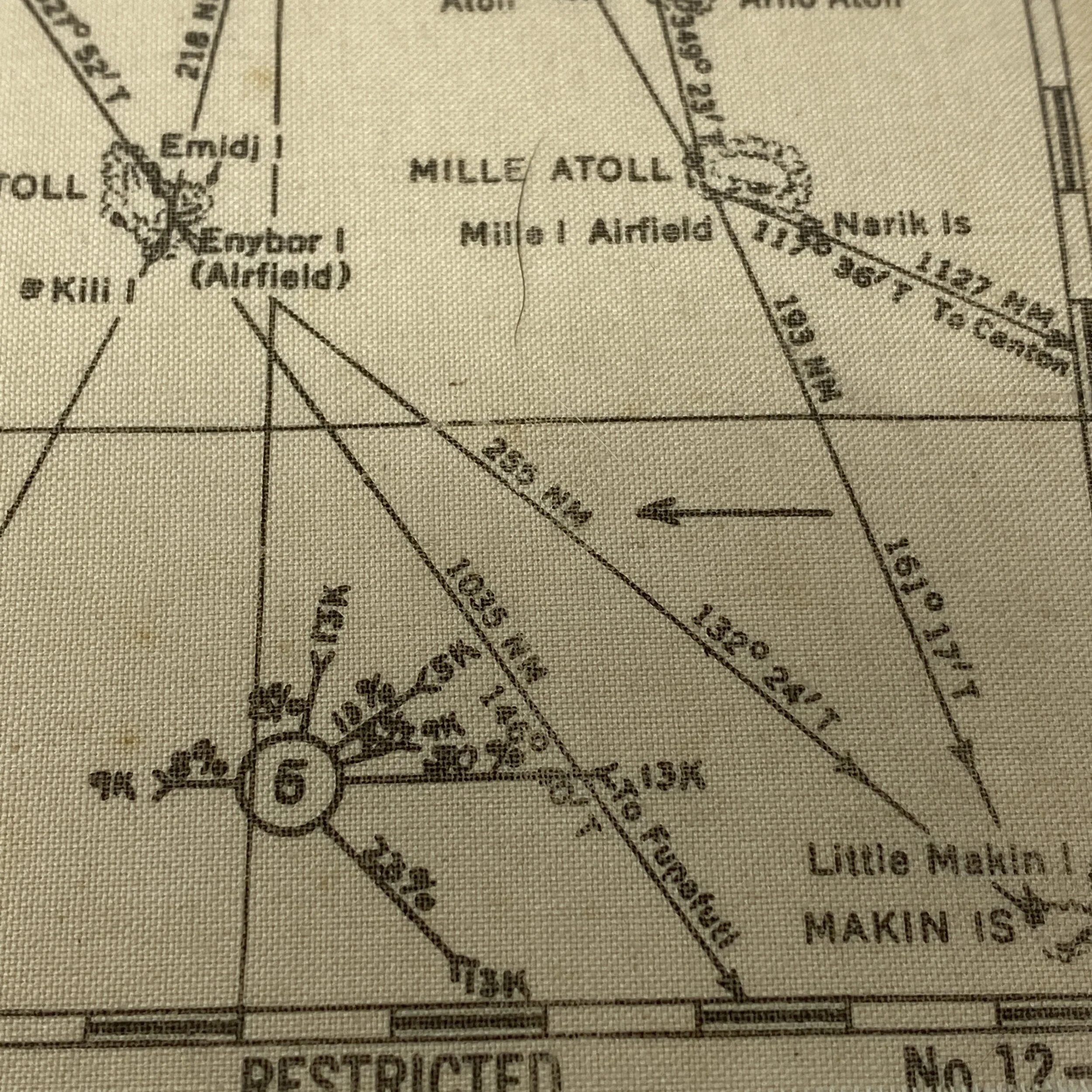

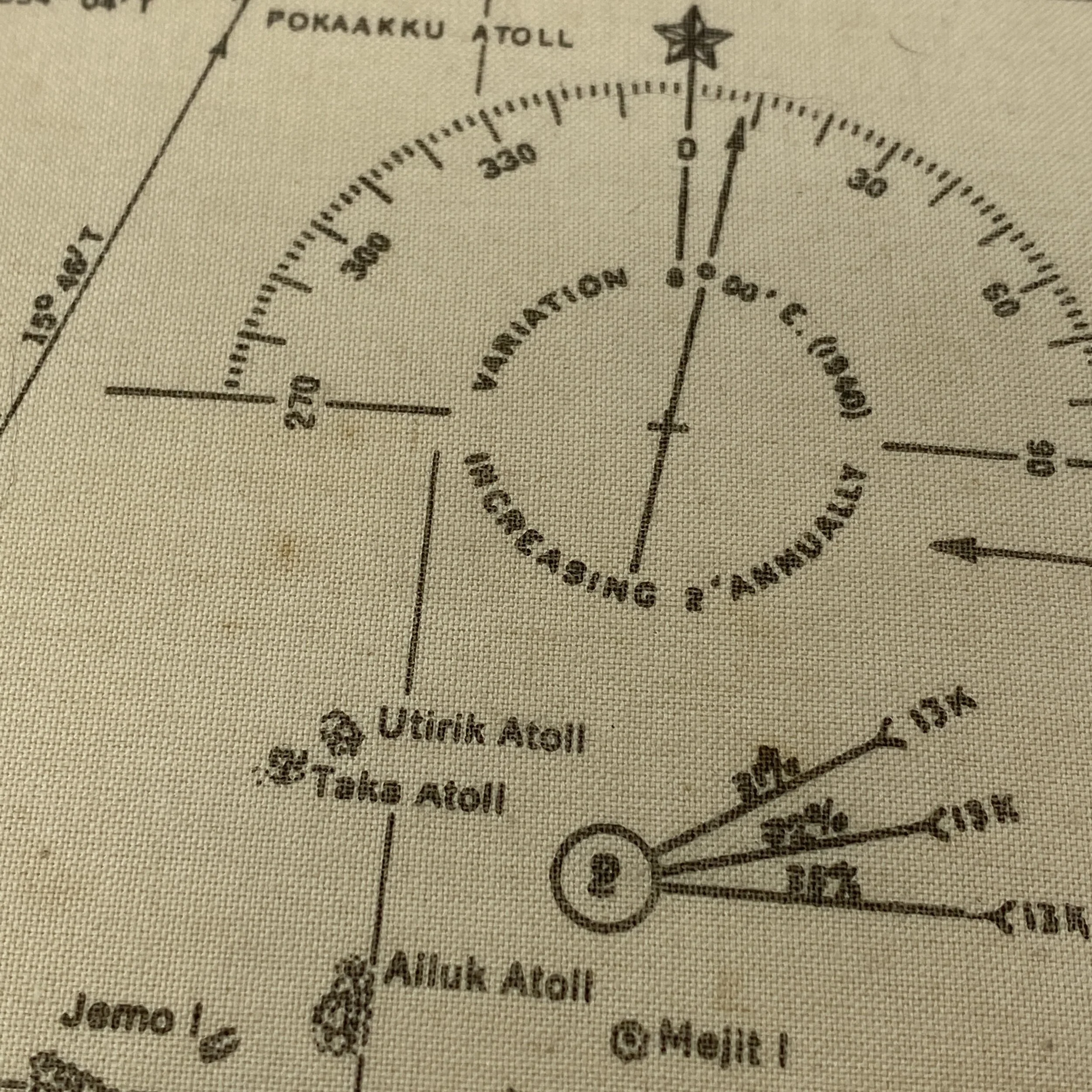

*USS Enterprise waterproof cloth pilot map shows the combat area and general map view of the Pacific Theater Marshall Islands Campaign (Kwajalein Jaluit, Makin, etc.). This pilot’s map features compass navigational aids located near the outside edge to aid carrier pilots in navigation while on attack missions and patrols against Japanese Naval and Air and defensive island installations in the area. This cloth map served as a survival and bail out map if the pilot were shot down in the Marshall islands region.

This extremely rare ‘RESTRICTED’ marked World War II cloth printed map was printed by the N.A.C.I. - Hydrographic Office and is dated July 1st, 1943. In the actual USS Enterprise ‘After Action’ reports it states, “It is recommended that "Top Secret" material - Operation Plans and Orders - be reclassified downward to "Secret or Confidential" prior to the start of an operation by a sufficient length of time to permit of adequate and timely distribution to subordinate officers and pilots concerned.” Maps and documents marked “Restricted” were done so when inside the designated combat area shown.

This map titled “Marshall Islands” was carried and used by Lt. Moore who served as an American pilot on the USS Enterprise (CV-6) Air Group. This rare waterproof survival cloth map was carried by Lt. Moore as U.S. aircraft patrols and search and destroy missions were conducted by the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and its Air Group during the USS Enterprise and its air group support U.S. and Allied efforts against the Japanese in their Marshall Islands Campaign. In order to preserve this survival map it was printed on a waterproof and weatherproof tan fine silk cloth and was usually worn around the necks (if long enough) or stuffed inside the pocket of the pilot. While there is no documentation of Lt. Moore being shot down in the Pacific Theater, this is the exact specially map and produced cloth map that would have been carried by every single one of the USS Enterprise (CV-6) Air Group pilots and crew. It was a good thing if you never needed to use this cloth map.

USS Enterprise and Kwajalein:

Like an athlete at the peak of her condition, Enterprise was tirelessly in action for the entire year. In January she raided Taroa, in the Marshall islands, and then sailed north to pound Kwajalein atoll in preparation for its occupation. In February, she launched raid after raid against Truk, Japan's feared mid-Pacific fortress, breaking her own record for the tonnage of bombs dropped in a single day, and launching the first night bombing attack in the history of naval warfare.

B3-2. Planes from ENTERPRISE bombed and strafed shore installations on Moloelap, Wotje and Kwajalein in the Marshalls, and bombed and torpedoed several enemy ships including one cruiser and two submarines. The raid set back Japanese plans for strengthening bases in the West Central Pacific, and provided the first good news after the disaster at Pearl Harbor. The opposite result might have occurred if ENTERPRISE had not successfully evaded two determined bombing attacks from Japanese land-based planes, receiving only minor damage from a near-miss.

G4-1. On 1 November, ENTERPRISE departed Puget Sound for Pearl Harbor where on 10 November she joined the task force which was to support the landings on Tarawa, Makin and Apamama in the Gilbert Islands. On board were newly organized teams of night fighters, "Bat Teams," each consisting of a radar-equipped Avenger torpedo plane and two Hellcat fighters. ENTERPRISE planes struck at Makin during the three-day period 19-21 November and during the nights of 24, 25 and 26 November her night fighters successfully repulsed attacks by Japanese torpedo bombers against the task force. ENTERPRISE withdrew on the afternoon of 28 November, her part in the operation against the three islands completed. On the way back to Pearl Harbor she circled north of the Marshalls in order to launch a strike against shipping and shore installations on Kwajalein. She arrived in Pearl Harbor 9 December.

G4-2. ENTERPRISE departed Pearl Harbor 16 December to participate in the landings on Kwajalein in the Marshalls. Operating to the south and west of the islands, she provided planes for the bombardment of enemy aircraft and ground installations, for combat air patrol, anti-submarine patrol, photographic reconnaissance and for direct support of landing troops. The Japanese offered comparatively little resistance. No special night fighters were required and the occupation was completed by 4 February.

USS Enterprise and Jaluit:

G4-3. On 16 February, planes from ENTERPRISE participated in strikes against shipping and oil storage installations at Truk. Although the major units of the Japanese Fleet had already left that base, six enemy combatant ships and many enemy auxiliaries were sunk or damaged. The strikes continued through the seventeenth. Then the U.S. carriers and their escorts retired rapidly to the northeast, pausing to launch two strikes against shore installations on Jaluit, 20 February.

In Enterprise, Halsey and his Chief of Staff, CDR Miles Browning, had developed a plan for the raid. The Yorktown force - commanded by Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher - would target Makin, in the Gilbert Islands, and Jaluit and Mili in the southern Marshalls. Halsey and Enterprise, accompanied by Spruance's cruisers, set their sights on Wotje and Taroa (in the Maloelap atoll) in the northern Marshalls. As the Marshalls were suspected of being well-defended, this seemed like a long enough list of targets. New intelligence received January 27, courtesy the submarine Dolphin SS-169, indicated they were not so heavily fortified as once thought, and reported significant enemy air and shipping activity at Kwajalein Atoll, 150 miles due west of Wotje. Browning - a brilliant and aggressive tactician at a time when the Navy desperately needed such men - convinced Halsey to add Kwajalein to his target list.

USS Enterprise and Taroa:

In Enterprise, Halsey and his Chief of Staff, CDR Miles Browning, had developed a plan for the raid. The Yorktown force - commanded by Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher - would target Makin, in the Gilbert Islands, and Jaluit and Mili in the southern Marshalls. Halsey and Enterprise, accompanied by Spruance's cruisers, set their sights on Wotje and Taroa (in the Maloelap atoll) in the northern Marshalls. As the Marshalls were suspected of being well-defended, this seemed like a long enough list of targets. New intelligence received January 27, courtesy the submarine Dolphin SS-169, indicated they were not so heavily fortified as once thought, and reported significant enemy air and shipping activity at Kwajalein Atoll, 150 miles due west of Wotje. Browning - a brilliant and aggressive tactician at a time when the Navy desperately needed such men - convinced Halsey to add Kwajalein to his target list.

Doing so entailed considerable risk. In order to bring Kwajalein within range of her bombers, Enterprise would have to operate dangerously close to enemy bases on Wotje and Taroa. Now, though, it was apparent that not striking Kwajalein would be just as dangerous. No matter what, Enterprise would be in range of enemy land-based bombers from the atoll. It was imperative that enemy airfields on Kwajalein and the other islands be struck, and struck hard, before they had opportunity to launch possibly killing blows against the vulnerable carrier.

For two more days, the two task forces cruised northwest together, the most notable event being Enterprise refueling underway the night of January 28. Under the best conditions - in daylight - refueling underway is a dangerous, exacting task. On this day, the oiler Platte did not finish refueling the other ships in TF 8 until after sunset. Enterprise eased alongside Platte at 1600 that night and steamed at her side for the next five-and-half-hours, the first capital ship in history to refuel underway at night. In another two years, this capability - refined and repeated until it was a matter of course - would enable US Navy warships to operate far from friendly anchorages for a month or more at a time, but on this night minds were on more immediate concerns.

On January 29, Yorktown, Enterprise, and their respective task forces parted ways, and early the next morning swept across the International Date Line into January 31. With less than 24 hours remaining before their first offensive mission of the war, the men of Enterprise and her Air Group prepared. Fighting Six installed homemade armor - literally made of boilerplate - behind the seat of each Wildcat, a vital if weighty addition their Japanese counterparts would never consider. Halsey ordered each ship rigged for towing and for being towed, not wanting to waste a minute should any ship need help escaping after the raid. Navigators and airmen poured over aged maps, picking out reefs and targets. At 1830, Task Force 8 began its final run-in to the launching point, the ocean waves hissing past hulls at 30 knots, each of Enterprise's four 13-ton propellers revolving 275 times a minute.

The night passed uneventfully until, at 0220, the officer of the watch reported sand blowing in his face. Halsey ordered the ship's position checked: its course based on old maps of questionable accuracy, the ship could have been moments from running aground. The officer then thought to taste a few grains of the "sand". Finding they were suspiciously sweet, he soon traced their source to a sailor on watch, stirring sugar into his coffee. Forty minutes later, at 0300, the ship's crew was awakened, and the Big E - still underway - prepared to launch her first strikes of the war.

The first missions were timed to reach their targets throughout the northern Marshall Islands simultaneously, just before 0700: the same time that Spruance's cruiser force was to commence bombardment of Wotje and Taroa. At 0430, Enterprise turned into the wind. Thirteen minutes later, six F4F Wildcats roared into the black night for Combat Air Patrol, followed immediately 36 Scouting Six and Bombing Six SBDs led by Enterprise Air Group commander CDR Howard L. Young. Just after 0500, a second strike of nine TBD Devastators from Torpedo Six, and an SBD delayed by engine trouble, rumbled down the Big E's flight deck. These 46 planes formed up in the dark - no easy task - and headed for Kwajalein Atoll, 155 miles away. At 0610, still nearly an hour before sunrise, twelve Fighting Six Wildcats were launched for Wotje and Taroa. One Wildcat pilot, ENS David W. Criswell, apparently became disoriented in the dark. His plane stalled shortly after takeoff and plunged into the sea: Criswell was never found. Considering the limited training given pilots in night operations before the war, it's remarkable there weren't further mishaps.

On this first strike, each Devastator torpedo plane was armed with three 500 lb instantaneous-fused bombs - rather than the usual torpedo - while the Dauntlesses each lugged a single 500 lb bomb as well as two 200 lb bombs. The Wildcats carried two 100 lb bombs each.

As the planes droned through the pre-dawn darkness, Spruance's cruisers closed range with Wotje and Taroa: Northampton and Salt Lake City would take Wotje, while Chester and several destroyers sidled up to Taroa.

Shortly before 0700, Gene Lindsey's torpedo planes broke off from the main body of Dauntlesses and headed for Kwajalein anchorage, some 44 miles south of Roi at the northern end of the atoll. "Brigham" Young's SBDs, meanwhile, grappled with darkness, low-lying fog, and decades-old maps, trying to identify Roi itself. At 0705, seven minutes after the strikes were scheduled to begin, and - more importantly - after the defenders on the ground had been alerted to their approach, they succeeded.

In a steep, gliding run, LCDR Halstead L. Hopping led his division of six SBDs through increasing anti-aircraft fire, releasing his bombs over the enemy's airfield, where even as the attack begin, fighters were scrambling into the air. As the lead plane, Hopping's SBD drew much of the defenders' fire and plunged into the sea after releasing its bomb: Hopping and his gunner, RM 1/c Harold Thomas, were lost. Scouting Six continued the attack, with Earl Gallaher and C. E. Dickinson each leading six SBDs into the fray. The bombers pummeled the airfield - destroying an ammunition dump, two hangars, and a radio station - and swung back around to strafe the base and parked planes on the ground. Enemy fighters and anti-aircraft fire claimed three more SBDs, but Enterprise's airmen put on a spirited defense and claimed three "Claudes" in exchange.

With Roi in a shambles, seven marauding VS-6 SBDs - their big 500 lb bombs still slung under their bellies - made off for Kwajalein anchorage, where more substantial targets had been reported by Torpedo Six commander Gene Lindsey. Discovering several merchant ships, submarines, and the cruiser Katori in the anchorage, Lindsey had immediately called for more planes. Over Roi, Young picked up and repeated Lindsey's alert - "Targets suitable for heavy bombs at Kwajalein anchorage" - before detaching Bombing Six with the seven accompanying Scouting Six planes. Young's broadcast was heard aboard Enterprise, where the remaining nine VT-6 Devastators were armed with torpedoes and readied for launch.

Lindsey's Devastators had surprised the anchorage, damaging several of the ships there while encountering only poorly-directed defensive fire. Bombing Six, led by LCDR William R. Hollingsworth, and the remaining planes of VS-6, followed up with a dive-bombing attack from 14,000 feet. On their departure, the transport Bordeaux Maru and subchaser Shonan Maru appeared to be sinking, a half dozen other ships were damaged, and 90 men including the area commander lay dead.

Comprehensive WWII combat history of USS Enterprise (CV-6):

The Yorktown class aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise (CV-6) was commissioned at Newport News, Virginia, on May 12, 1938. Relocating to the Pacific, she was at sea during the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Three days after, she became the first U.S. Navy warship to sink a Japanese warship, submarine I-70, and later that month participated in the Wake Island expedition. In April, Enterprise covered the Dootlittle Raid on Japan and participated in the Battle of Midway that June, where her planes helped sink three Japanese aircraft carriers and a cruiser. During the Guadalcanal Campaign, she covered the landings and participated in the battles of Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz Islands. Despite being damaged in both battles, she launched aircraft to assist the ships involved in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. In late 1943 and early 1944, Enterprise took part in the Gilberts and Marshall invasions and air attacks on the Japanese in the Central and Southern Pacific. In the summer of 1944, she participated in the Marianas operation and the Battle of the Philippine Sea, followed with the largest naval battle in history, the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October.In February 1945, Enterprise took part in the Iwo Jima invasion, then raids on the Japanese home islands and the Okinawa campaign in April. Due to damage received by two kamikaze attacks in April and May, she returned to the United States with the distinction of being the most decorated U.S. Navy warship during the war. Following Japan's surrender, she helped transport U.S. servicemen back to the United States. Decommissioned in February 1947, Enterprise was re-designated (CVA-6) in October 1952 and then to (CVS-6) in August 1953. Despite efforts to turn her into a museum ship, she was sold for scrapping in July 1958.