RARE! WWII USS Solace (AH-5) Original TYPE ONE Iwo Jima Invasion Photograph

RARE! WWII USS Solace (AH-5) Original TYPE ONE Iwo Jima Invasion Photograph

Comes with a C.O.A. and a full historical write-up.

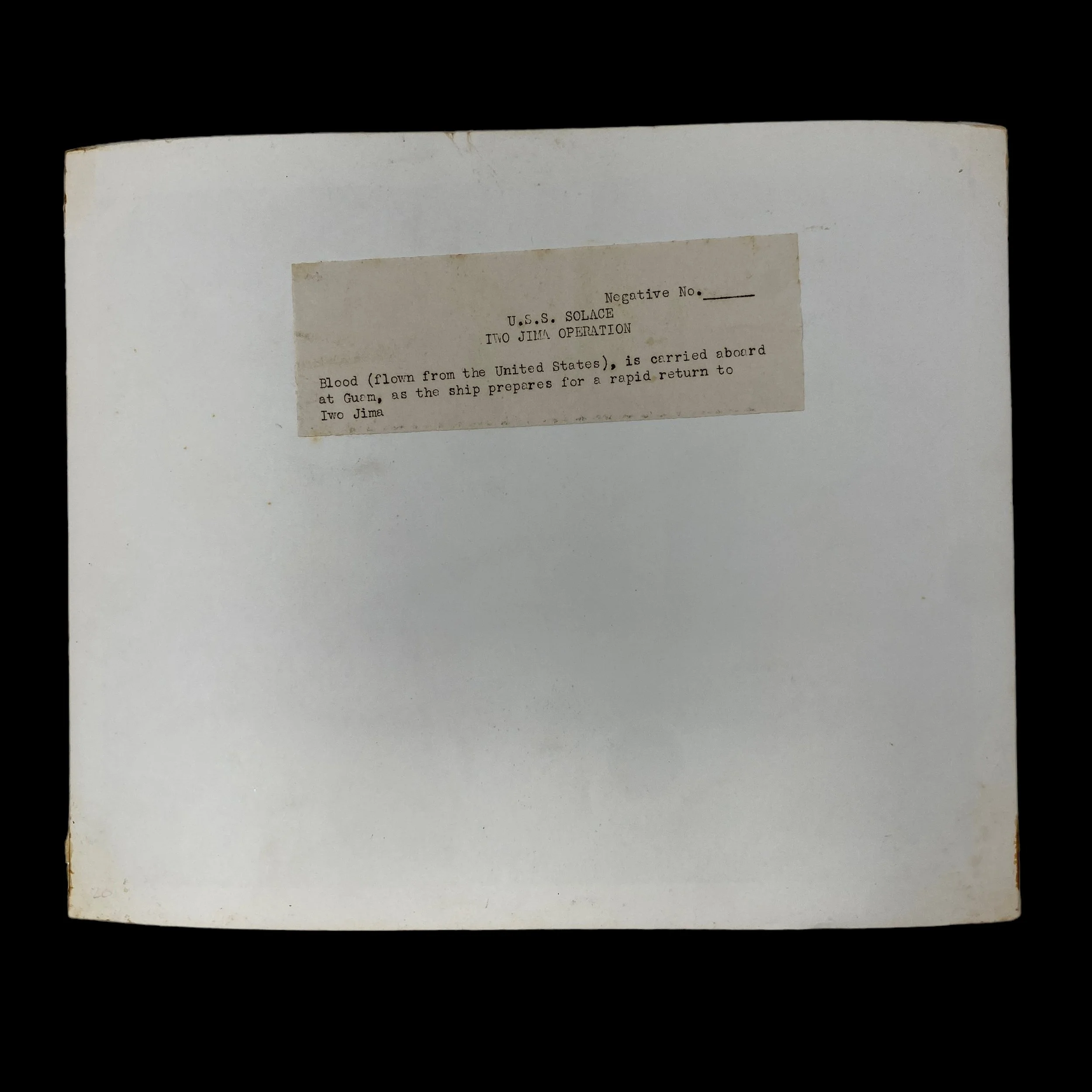

This incredibly rare and museum-grade WWII original TYPE ONE Iwo Jima photograph is one of only a few handfuls of original TYPE ONE original Iwo Jima invasion photographs availbe in the public sector. Taken directly by the USS Solace and marked “USS SOLACE - IWO JIMA OPERATIONS” with the original paper backing this photograph shows soldiers loading supplies aboard to Guam to return to aid in the Iwo Jima invasion.

“The USS Solace proceeded to Guam and was dispatched from there to Iwo Jima, arriving on 23 February. Solace anchored within 2,000 yards (1,800 m) of the beach, but enemy shells fell within 100 yd (91 m) of her, and she was forced to move further out. The first wounded were brought on board within 45 minutes of her arrival, and she sailed for Saipan the next day, loaded to capacity. She made three evacuation trips from Iwo Jima to base hospitals at Guam and Saipan, carrying almost 2,000 patients, by 12 March. The island was declared secure on the 15th.”

Full Combat History of the USS Solace:

Solace was at Pearl Harbor during the attack of 7 December 1941. As an unarmed hospital ship, she was unable to participate in defending against the Japanese aircraft. A crew member filming from the deck of that ship, an Army medical doctor named Eric Haakenson, captured the precise moment of USS Arizona's explosion.[3] She immediately sent her motor launches with stretcher parties to the stricken and burning battleship Arizona to evacuate the wounded, and pulled men from the water which was covered in burning oil. After several trips to Arizona and West Virginia, the boat crews then assisted Oklahoma.[4] Honoring the rules of the Geneva Convention, the attacking Japanese aircraft did not hit Solace due to her white paint and red crosses. She was one of the few ships not damaged during the attack.

In March 1942, Solace was ordered to the South Pacific and preceded to Pago Pago, Samoa. From there, she sailed to the Tonga Islands, arrived at Tongatapu on 15 April, and remained there until 4 August. On that day, she got underway and steamed, via Nouméa, New Caledonia, to New Zealand. She arrived at Auckland on the 19th and discharged her patients. From then until May 1943, Solace shuttled between New Zealand, Australia, New Caledonia, Espiritu Santo, the New Hebrides, and the Fiji Islands, caring for fleet casualties and servicemen wounded in the island campaigns under desperate circumstances. For example, on 14 January 1943, one hospital corpsman and 99 patients were transferred aboard from U.S. Advanced Hospital Base Button at Espiritu Santo with 369 patients already on board, far exceeding official patient capacity.[5] Patients whom she could not return to duty shortly were evacuated to hospitals for more prolonged care.

From June–August, she operated as a station hospital ship at Nouméa. On 30 August, Solace sailed to Efate, New Hebrides, and performed the same duties at that port until sailing for Auckland on 3 October. On the 22nd, the hospital ship departed New Zealand and proceeded via Pearl Harbor to the west coast of the United States. She arrived at San Francisco on 9 November; disembarked her patients; and, on the 12th, sailed for the Gilberts.

Solace arrived at Abemama Island on the 24th, embarked casualties from the Tarawa campaign, sailed the same day for Hawaii, and arrived at Pearl Harbor on 2 December.

On 17 December, Solace sailed from Oahu with embarked patients to be evacuated to the U.S. She arrived at San Diego on 23 December 1943.

Solace remained in San Diego until she sailed on 15 January 1944 for the Marshall Islands. She arrived at Roi on 3 February and departed the next day with a load of wounded for Pearl Harbor. She was there for one day, returned to Roi on 18 February, then proceeded toward Eniwetok on the 21st. After picking up 391 casualties (of whom 125 had been brought by landing craft directly from the beachheads at Eniwetok and Parry Island), she returned to Pearl Harbor on 3 March.

Solace was next ordered to Espiritu Santo and arrived there on 20 March. During the next nine weeks, she shuttled between New Guinea, the Admiralty Islands, and Australia. She was back at Roi on 6 June and departed there nine days later for the Marianas. The hospital ship anchored in Charan-Kanoa Anchorage, Saipan, on 18 June. While the shores and hills were still under bombardment, she began taking on battle casualties, many directly from the front lines. When she sailed for Guadalcanal on the 20th, all of her hospital beds were filled, and there were patients in the crew's quarters. Altogether, the ship was caring for 584 men. Solace returned to Saipan from 2–5 July and embarked another load of wounded whom she took to the Solomons. From there, she was routed to the Marshalls arriving at Eniwetok on the 19th. Two days later, she sailed for Guam. Between 24 and 26 July, she took on board wounded from various ships and the beachhead for evacuation to Kwajalein. Solace was back at Guam from 5–15 August where she picked up 502 casualties for evacuation to Pearl Harbor.

Solace was at Pearl Harbor from 26 August – 7 September, when she left for the Marshalls. She arrived at Eniwetok on the 14th. Three days later, she was ordered to sail immediately for the Palaus. She arrived off Peleliu on the 22nd, anchored 2,000 yd (1,800 m) from the beach, and began loading wounded. All stretcher cases (542) were put on board Solace. She headed for Nouméa on the 25th and arrived on 4 October. The ship was back at Peleliu from 16 to 27 October tending wounded and then sailed to Manus.

Solace stood out of Seeadler Harbor on 29 October, bound for the Caroline Islands. From 1 November 1944 – 18 February 1945, she served as a station hospital ship at Ulithi, providing medical and dental care for the 3rd and 5th Fleets. She proceeded to Guam and was dispatched from there to Iwo Jima, arriving on 23 February. Solace anchored within 2,000 yards (1,800 m) of the beach, but enemy shells fell within 100 yd (91 m) of her, and she was forced to move further out. The first wounded were brought on board within 45 minutes of her arrival, and she sailed for Saipan the next day, loaded to capacity. She made three evacuation trips from Iwo Jima to base hospitals at Guam and Saipan, carrying almost 2,000 patients, by 12 March. The island was declared secure on the 15th.

Solace steamed to Ulithi and joined the invasion fleet for Okinawa Gunto. She arrived at Kerama Retto on the morning of 27 March and began bringing patients on board from various ships. In the next three months, the ship evacuated seven loads of casualties to the Marianas. On 1 July, she sailed from Guam to the west coast, via Pearl Harbor. Solace arrived at San Francisco on 22 July and was routed to Portland, Oregon, for an overhaul that lasted until 12 September. She was then assigned to "Operation Magic Carpet", transporting homecoming veterans from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco. She returned to San Francisco from her last voyage on 16 January 1946 and was routed to Hampton Roads, Virginia.

Pre-Invasion Bombardment:

Initial carrier raids against Iwo Jima began in June 1944. Prior to the invasion, the 8-square-mile island would suffer the longest, most intensive shelling of any Pacific island during the war. The 7th Air Force, working out of the Marianas, supplied the B-24 heavy bombers for the campaign.

In addition to the air assaults on Iwo, the Marines requested 10 days of pre-invasion naval bombardment. Due to other operational commitments and the fact that a prolonged air assault had been waged on Iwo Jima, Navy planners authorized only three days of naval bombardment. Unfavorable weather conditions further hampered its effects. Despite this, VADM Turner decided to keep the invasion date, 19 February 1945, as planned, and the Marines prepared for D-day.

D-day:

More than 450 ships massed off Iwo as the H-hour bombardment pounded the island. Shortly after 9:00am, Marines of the 4th and 5th Divisions hit beaches Green, Red, Yellow and Blue abreast, initially finding little enemy resistance. Coarse volcanic sand hampered the movement of men and machines as they struggled to move up the beach. As the protective naval gunfire subsided to allow for the Marine advance, the Japanese emerged from their fortified underground positions to begin a heavy barrage of fire against the invading force.

The 4th Marine Division pushed forward against heavy opposition to take the Quarry, a Japanese stronghold. The 5th Marine Division’s 28th Marines had the mission of isolating Mount Suribachi. Both tasks were accomplished that day.

The Battle Continues:

On 20 February, one day after the landing, the 28th Marines secured the southern end of Iwo and moved to take the summit of Suribachi. By day’s end, one third of the island and Motoyama Airfield No. 1 was controlled by the Marines. By 23 February, the 28th Marines would reach the top of Mount Suribachi and raise the U.S. flag.

The 3d Marine Division joined the fighting on the fifth day of the battle. These Marines immediately began the mission of securing the center sector of the island. Each division fought hard to gain ground against a determined Japanese defender. The Japanese leaders knew with the fall of Suribachi and the capture of the airfields that the Marine advance on the island could not be stopped; however, they would make the Marines fight for every inch of land they won.

Lieutenant General Tadamishi Kuribayashi, commander of the Japanese ground forces on Iwo Jima, concentrated his energies and his forces in the central and northern sections of the island. Miles of interlocking caves, concrete blockhouses and pillboxes proved to be some of the most impenetrable defenses encountered by the Marines in the Pacific.

The Marines worked together to drive the enemy from the high ground. Their goal was to capture the area that appropriately became known as the “Meat Grinder.” This section of the island included three distinct terrain features: Hill 382, the highest point on the northern portion of the island; an elevation known as “Turkey Knob,” which had been reinforced with concrete and was home to a large enemy communications center; and the “Amphitheater,” a southeastern extension of Hill 382.

The 3d Marine Division encountered the most heavily fortified portion of the island in their move to take Airfield No. 2. As with most of the fighting on Iwo Jima, frontal assault was the method used to gain each inch of ground. By nightfall on 9 March, the 3d Marine Division reached the island’s northeastern beach, cutting the enemy defenses in two.

On the left of the 3d Marine Division, the 5th Marine Division pushed up the western coast of Iwo Jima from the central airfield to the island’s northern tip. Moving to seize and hold the eastern portion of the island, the 4th Marine Division encountered a “mini banzai” attack from the final members of the Japanese Navy serving on Iwo. This attack resulted in the death of nearly 700 Japanese and ended the centralized resistances of enemy forces in the 4th Marine Division’s sector. The 4th Marine Division would join forces with the 3d and 5th Marine Divisions at the coast on 10 March.

Operations entered the final phases 11 March. Enemy resistance was no longer centralized and individual pockets of resistance were taken one by one. Finally on 26 March, following a banzai attack against troops and air corps personnel near the beaches, the island was declared secure. The U.S. Army’s 147th Infantry Regiment assumed ground control of the island on 4 April, relieving the largest body of Marines committed in combat to any one operation during World War II.

Background: The invasion of Iwo Jima:

Iwo Jima, whose name translates as “Sulfur Island,” was an important midway point between South Pacific bomber bases that were already in the hands of the Allies and the Japanese home islands. 700 miles from Tokyo and 350 from the nearest U.S. airbase, with a central plain suitable for large runways, American planners viewed it as a valuable target. Following months of bombardment, the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions began landing on the island on February 19, 1945.

Despite the sophistication of the American intelligence effort and the overwhelming force brought to bear, the invasion was extraordinarily costly. American planners failed to understand the defensive strategy of Japanese General Kurabayashi or the complexity and extent of the Japanese fortifications, which included a huge network of linked underground bunkers, well-hidden and -protected artillery positions, interlocking fields of fire, and some 11 miles of tunnels. They also vastly overestimated the impact of the months-long pre-invasion bombardment, which left these fortifications largely intact on the day of the invasion. Indeed, one recent writer quotes Admiral Chester Nimitz, American Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, as having said “Well, this will be easy. The Japanese will surrender Iwo Jima without a fight.” (Derrick Wright, The Battle for Iwo Jima, p. 51)

The battle for the island was among the bloodiest of the Pacific Theater of the Second World War. In total, more than 6,800 U.S. Marines lost their lives and more than 19,000 were wounded, while a staggering 18,000 of the roughly 20,000 Japanese defenders were killed. In light of these terrible losses, there was, and still is, dispute about whether the invasion had been merited.

In all, a rare photographic artifact from one of the great battles of the Second World War.