WWII 1945 German POW Revised "Cologne Story" US-British Surrender SHAEF Leaflet

WWII 1945 German POW Revised "Cologne Story" US-British Surrender SHAEF Leaflet

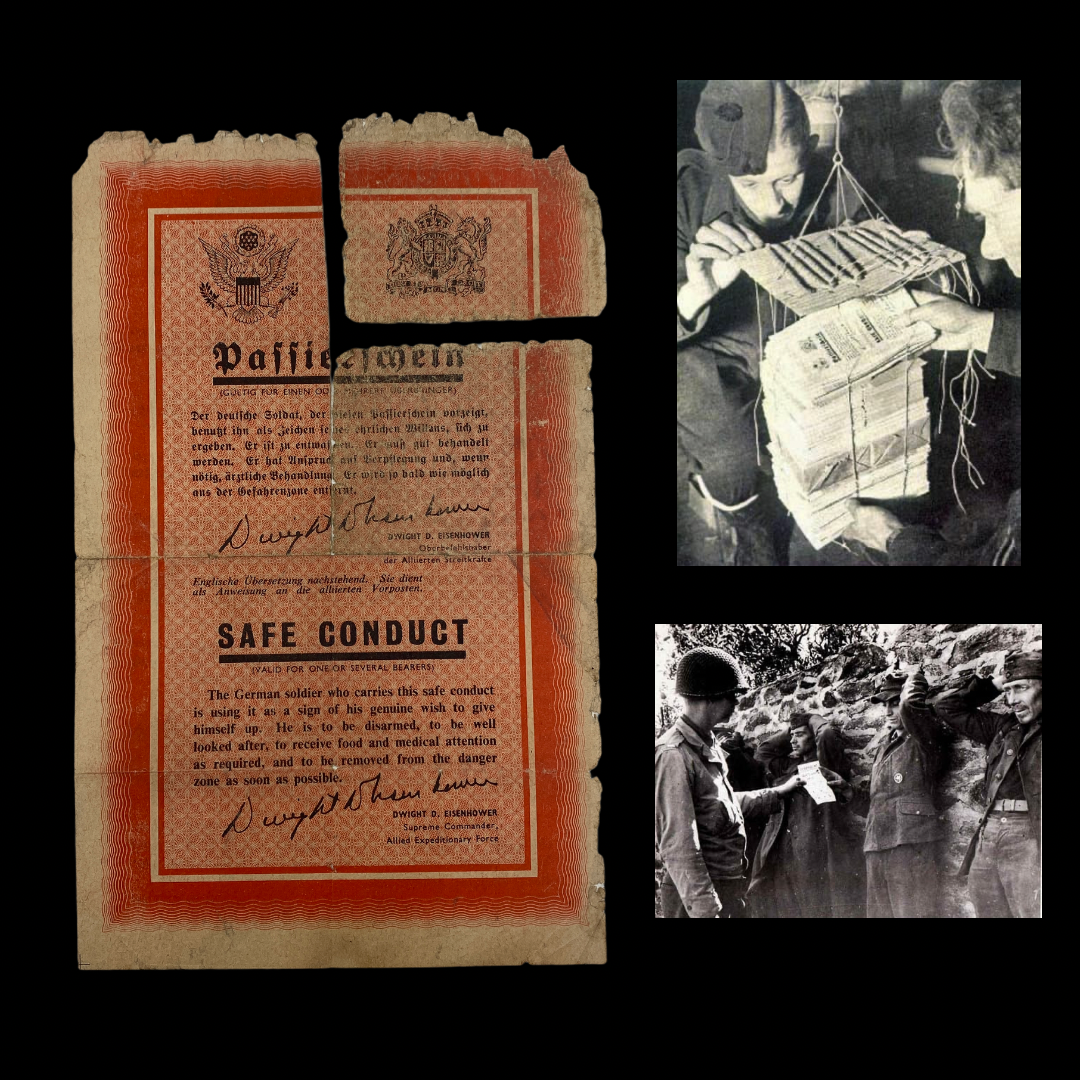

Printed in Waterlows of London, this safe-conduct surrender leaflet (US/GB ZG90K 1945) was a combined US-British SHAEF leaflet that was airdropped on German positions. First produced and distributed soon after the Normandy invasion, the early Passierschein contained the seal of the United States and the British royal crest; its text, in English and German, directed Allied frontline troops to give good treatment to surrendering Germans. As the campaign continued, a series of improvements was made in the leaflet, based on results of prisoner-of-war interviews. Martin Herz recalled that by the time the Passierschein went into its sixth printing, the following changes had been made: (a) the German text was placed above the English; (b) a note specifically stated that the English text was a translation of the German; (c) General Eisenhower's signature was added; (d) his name was spelled out after it had been learned Germans did not recognize his handwriting; (e) the leaflet color was changed from green to a more conspicuous red; (f) under the word “Safe Conduct,” a note was added stating that the document was valid for “one or several bearers.” Continuous interrogations of the German prisoners had netted these improvements.

Rarer printed version with an amazing historically documented story!

Robert Visser, an eighteen-year-old Dutch student who had been arrested by the Germans in November 1944 saw the ZG-90 passierschein in action. He says in part:

On 2 March 1945 there was intensive shelling of Oberaussem, located between Aachen and Cologne. The Germans and Americans were shooting at each other with howitzers. There were four German soldiers in the shelter that were uncertain about what to do. I talked to them and suggested that if they intended to fight they should leave the shelter and not expose the civilians to harm. I also told them that I could speak English and could assist them in surrendering. After some back-and-forth talk they informed me that they would not fight and intended to surrender. They had copies of the ZG-90 “safe conduct” leaflets that had been dropped by the millions from Allied planes. These safe conduct passes were addressed to German soldiers and told them that they would be treated humanely if they surrendered.

About 4:30 p.m. we heard machine guns just outside the shelter. Then the door to the shelter splintered and the area near the door was sprayed by machine gun fire.

On some other Allied propaganda leaflets it was stated that those who wanted to surrender needed to shout as loud as possible “Ei Sorrender.” I took that message to heart and started yelling as loud as I could “I surrender! We surrender!” The German soldiers shouted “Wir Ergeben Uns.” After a short time, which seemed like an eternity, we heard the words, “Come here.” I told the German soldiers to raise their arms and marched them outside. The three American soldiers burst out laughing when they saw my disheveled personage bringing out four frightened prisoners of war. The GI’s shook my hand, patted me on the back and started playing Santa Claus. They gave me chewing gum, cigarettes, grapefruit juice and a can of corned beef. The two soldiers and sergeant were from the 395th Regimental Combat Team attached to the Third Armored Division.

The translated German text on the back reads:

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW REGARDING PRISONERS OF WAR

(According to the Hague Convention, 1907, and the Geneva Convention, 1929)

1. From the moment of surrender, German soldiers are regarded as P.O.W.s and come under the protection of the Geneva Convention. Accordingly, their military honor is fully respected.

2. P.O.W.s must be taken to assembly points as soon as possible, which are far enough from the danger zone to safeguard their personal security.

3. P.O.W.s receive the same rations, qualitatively and quantitatively, as members of the Allied armies, and, if sick or wounded, are treated in the same hospitals as Allied troops.

4. Decorations and valuables are to be left with the P.O.W.s. Money may be taken only be officers of the assembly points and receipts must be given.

5. Sleeping quarters, accommodation, bunks and other installations in P.O.W. camps must be equal to those of Allied garrison troops.

6. According to the Geneva Convention, P.O.W.s must not become subject of reprisals nor be exposed to public curiosity. After the end of the war they must be sent home as soon as possible.

Soldiers in the meaning of the Hague Convention (IV, 1907) are: All armed persons, who wear uniforms or any insignias which can be recognized from a distance.

RULES FOR SURRENDER

To prevent misunderstanding when surrendering, the following procedure is advisable: Lay down arms, take off helmet and belt, raise your hands and wave a handkerchief or this leaflet.

By the time the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the British, French and Russians had already printed and dropped a host of surrender leaflets on the German Army. The leaflets were of different sizes, colors, texts, and even the surrender instructions were different. There was no overall guidance, and certainly no uniformity. This all changed with the arrival of American troops in the United Kingdom and the strong alliance between the U.S. and British psy-warriors. For the first time the two allied nations worked together to prepare a standardized safe conduct leaflet that would be exactly the same wherever used. The final version of the "passierschein" has been called the most effective single leaflet of the war. It was considered so powerful that in 1944 the Allied Supreme Headquarters issued a directive forbidding reproduction of the safe conduct pass on other leaflets. They wanted to protect the authenticity of the document.

The story of the "passierschein" ("safe conduct pass") for Germany is interesting because of the alleged belief on the part of the Allies that the German officer or soldier would react in a positive way to an official-looking document. Therefore, the Americans and British collaborated to produce a fancy official document bearing national seals and signatures that would rival a stock certificate. They produced the leaflets late in the war in various formats with different code numbers. Germans liked things done in an official and formal manner, even in the midst of chaos, catastrophe, and defeat.

The Allied obliged, and gave the Germans various forms of very official-looking ‘surrender passes.’ One is printed in red and has a banknote-type engraving which makes it resemble a soap-premium coupon. This safe conduct pass was generally regarded as the most successful leaflet produced by the Psychological Warfare Branch of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF)…everything about the leaflet was designed to appear authoritative: the format handsomely engraved on good paper in a rich color, has been described as "looking like a college diploma. In phrasing Safe-Conducts, Allied leaflet writers considered it essential to expound constantly the good treatment theme and Allied adherence to the Geneva Convention. These promises were printed on the back of the pass. Sometimes, however, the leaflets seemed to promise so much (i.e., hospital care, mail privileges, education) that the Germans were skeptical.