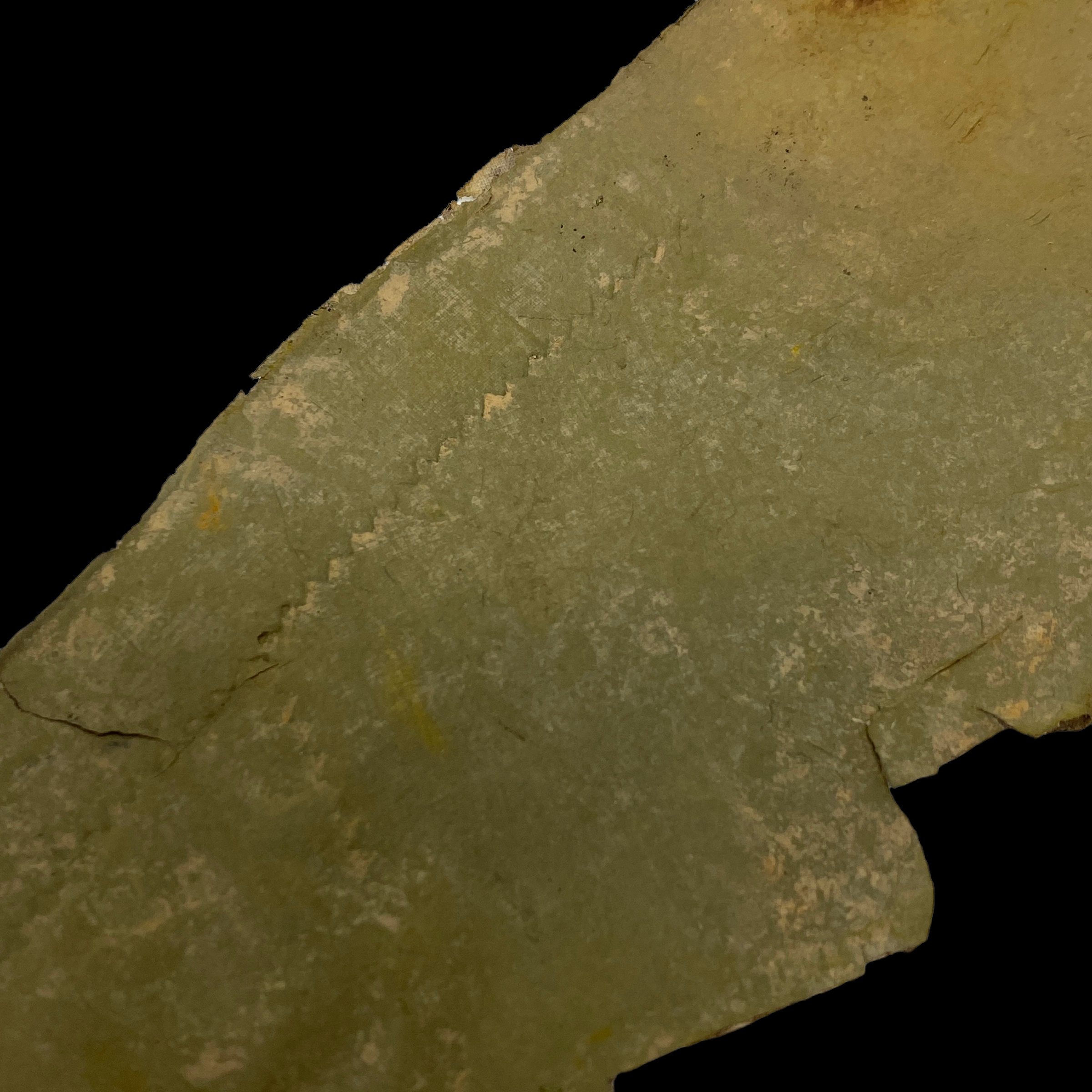

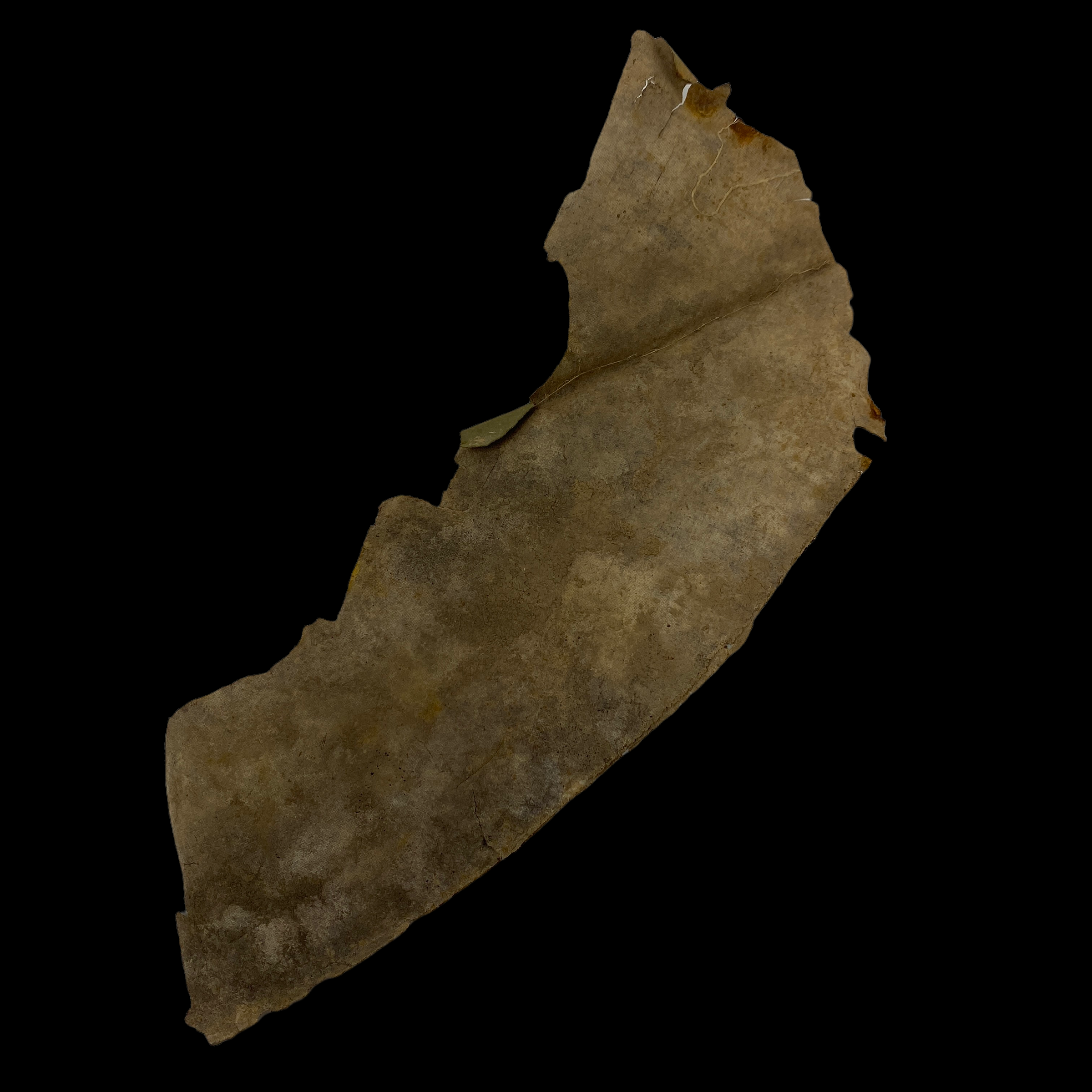

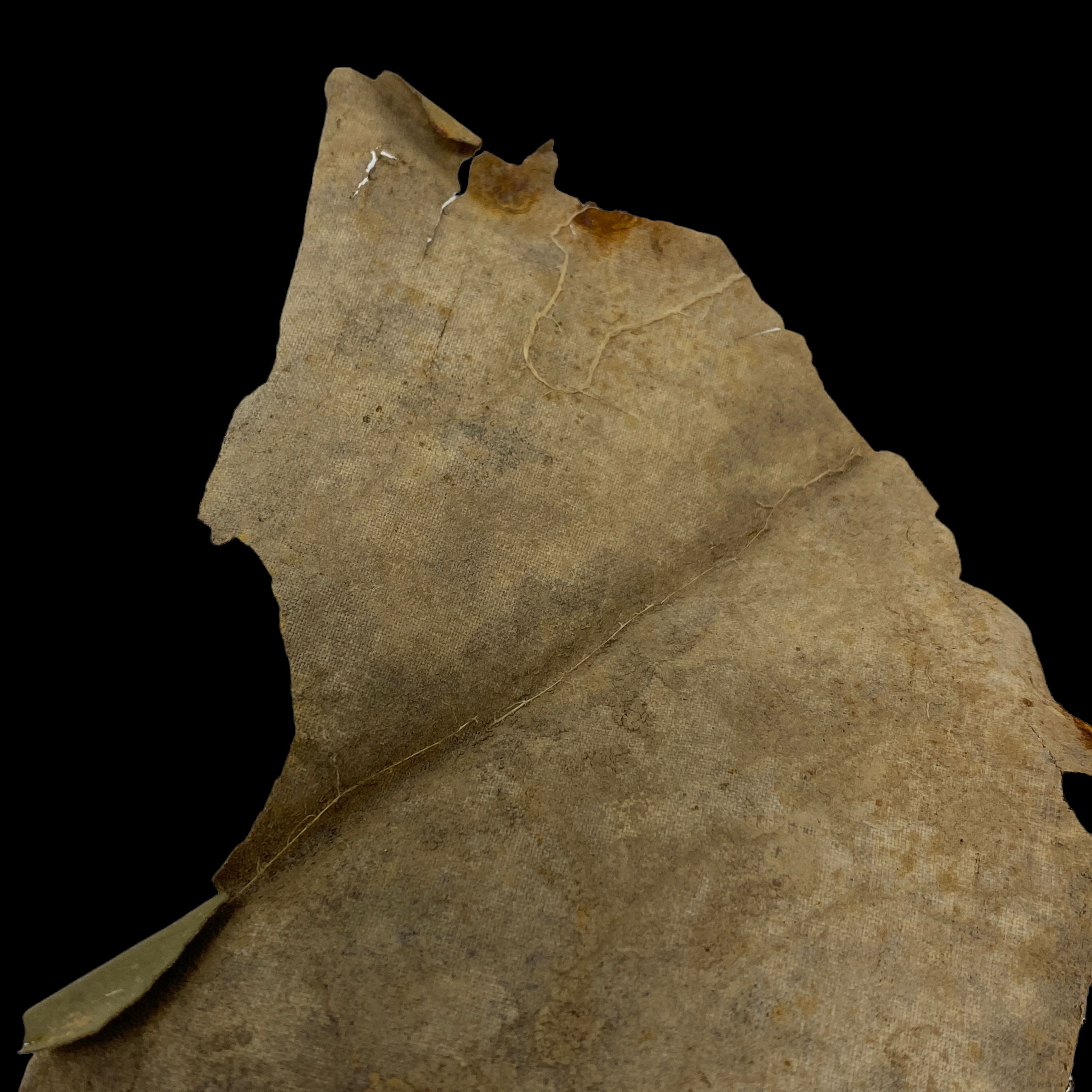

EXTREMELY RARE! WWII 1944 Operation Market Garden Waco CG-4 Glider Canvas Fabric #003

EXTREMELY RARE! WWII 1944 Operation Market Garden Waco CG-4 Glider Canvas Fabric #003

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

This incredibly rare and museum-grade Waco CG-4 glider fabric was recovered from one of the Allied gliders that participated in the infamous 1944 airborne assault of Operation Market Garden, one of the largest airborne operation in history. This fabric is the outside camouflaged/painted fabric and was recovered from one of the Operation Market Garden glider landing zones.

On the morning of September 17, 1944, three divisions of the First Allied Airborne Army—the U.S. 101st and 82nd Airborne and the British 1st Airborne—began flying from bases in England across the North Sea to the Netherlands. The 101st Airborne was tasked with capturing Eindhoven, as well as several bridges over the canals and rivers north of that town, while the 82nd Airborne was ordered to capture territory around Nijmegen, including a key bridge over the River Waal.

Expendable American combat gliders were used on some of the most dangerous missions of the war, that of landing troops and equipment miles behind enemy lines. Towed into the air by tug aircraft, CG-4’s went into operation in 1943 during the Allied invasion of Sicily. They also played a critical role in the D-Day assault on June 6, 1944 and in other major airborne operations in the European and Pacific theatres. Glider landings were extremely hazardous due to heavy anti-aircraft fire, air traffic congestion and small landing zones often with obstructions. It was not considered desirable duty.

Code-named Market Garden, the offensive called for three Allied airborne divisions (the “Market” part of the operation) to drop by parachute and glider into the Netherlands, seizing key territory and bridges so that ground forces (the “Garden”) could cross the Rhine. Delivering over 34,600 men of the 101st, 82nd and 1st Airborne Divisions and the Polish Brigade. 14,589 troops were landed by glider and 20,011 by parachute. Gliders also brought in 1,736 vehicles and 263 artillery pieces. 3,342 tons of ammunition and other supplies were brought by glider and parachute drop.

The First Allied Airborne Army had been created on 16 August as the result of British requests for a coordinated headquarters for airborne operations, a concept approved by General Eisenhower on 20 June. The British had strongly hinted that a British officer – Browning in particular – be appointed its commander. Browning for his part decided to bring his entire staff with him on the operation to establish his field HQ using the much-needed 32 Horsa gliders for administrative personnel, and six Waco CG-4A gliders for U.S. Signals' personnel. Since the bulk of both troops and aircraft were American, Brereton, a U.S. Army Air Forces officer, was named by Eisenhower on 16 July and appointed by SHAEF on 2 August. Brereton had no experience in airborne operations but had extensive command experience at the air force level in several theaters, most recently as commander of Ninth Air Force, which gave him a working knowledge of the operations of IX Troop Carrier Command.

Market would be the largest airborne operation in history, delivering over 34,600 men of the 101st, 82nd and 1st Airborne Divisions and the Polish Brigade. 14,589 troops were landed by glider and 20,011 by parachute. Gliders also brought in 1,736 vehicles and 263 artillery pieces. 3,342 tons of ammunition and other supplies were brought by glider and parachute drop.

To deliver its 36 battalions of airborne infantry and their support troops to the continent, the First Allied Airborne Army had under its operational control the 14 groups of IX Troop Carrier Command, and after 11 September the 16 squadrons of 38 Group (an organization of converted bombers providing support to resistance groups) and a transport formation, 46 Group.

The combined force had 1,438 C-47/Dakota transports (1,274 USAAF and 164 RAF) and 321 converted RAF bombers. The Allied glider force had been rebuilt after Normandy until by 16 September it numbered 2,160 CG-4A Waco gliders, 916 Airspeed Horsas (812 RAF and 104 U.S. Army) and 64 General Aircraft Hamilcars. The U.S. had only 2,060 glider pilots available, so that none of its gliders would have a co-pilot but would instead carry an extra passenger.

Because the C-47s served as paratrooper transports and glider tugs and because IX Troop Carrier Command would provide all the transports for both British parachute brigades, this massive force could deliver only 60 percent of the ground forces in one lift. This limit was the reason for the decision to split the troop-lift schedule into successive days. Ninety percent of the USAAF transports on the first day would drop parachute troops, with the same proportion towing gliders on the second day (the RAF transports were almost entirely used for glider operations). Brereton rejected having two airlifts on the first day, although this had been accomplished during Operation Dragoon, albeit with slightly more daylight (45 minutes) and against negligible opposition.

17 September was on a dark moon and in the days following it the new moon set before dark. Allied airborne doctrine prohibited big operations in the absence of all light, so the operation would have to be carried out in daylight. The risk of Luftwaffe interception was judged small, given the crushing air superiority of Allied fighters but there were concerns about the increasing number of flak units in the Netherlands, especially around Arnhem. Brereton's experience with tactical air operations judged that flak suppression would be sufficient to permit the troop carriers to operate without prohibitive loss. The invasion of Southern France had demonstrated that large scale daylight airborne operations were feasible. Daylight operations, in contrast to those in Sicily and Normandy, would have much greater navigational accuracy and time-compression of succeeding waves of aircraft, tripling the number of troops that could be delivered per hour. The time required to assemble airborne units on the drop zone after landing would be reduced by two-thirds.

IX Troop Carrier Command's transport aircraft had to tow gliders and drop paratroopers, duties that could not be performed simultaneously. Although every division commander requested two drops on the first day, Brereton's staff scheduled only one lift based on the need to prepare for the first drop by bombarding German flak positions for half a day and a weather forecast on the afternoon of 16 September (which soon proved erroneous) that the area would have clear conditions for four days, so allowing drops during them.