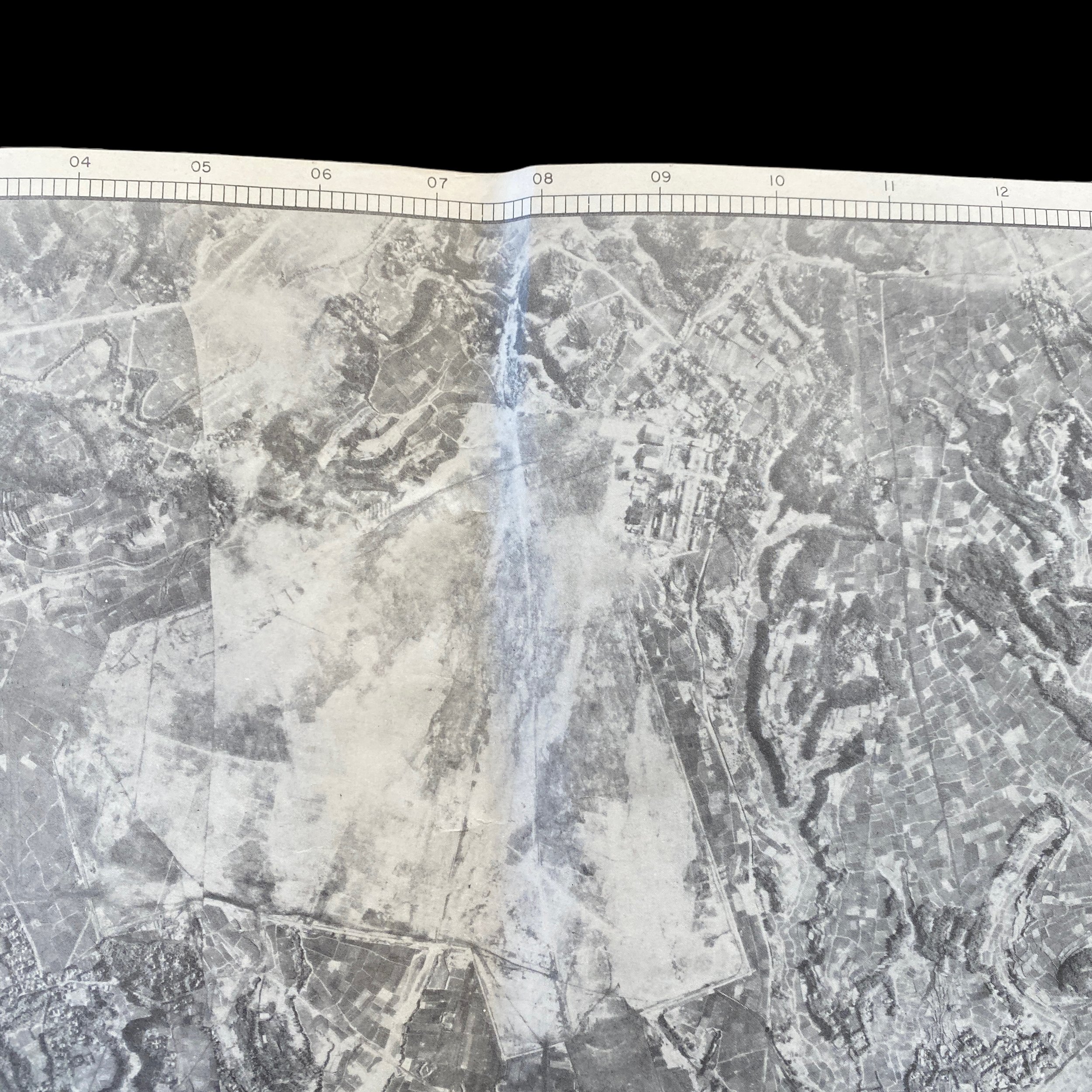

RARE! WWII 1945 B-29 Navigator XXI Bomber Command SOUTH KYUSHU AREA (CHIRAN AIRFIELD) JAPAN Target Air Raid Mission Target Photo Map*

RARE! WWII 1945 B-29 Navigator XXI Bomber Command SOUTH KYUSHU AREA (CHIRAN AIRFIELD) JAPAN Target Air Raid Mission Target Photo Map*

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

These XXI Bomber Command target photo maps rarely come up for sale in the public sector. This is a once in a timeline chance to own a piece of B-29 WWII history.

B-29 Air Raid on SOUTH KYUSHU AREA - CHIRAN AIRFIELD

This incredibly scare and museum-grade ‘RESTRICTED’ WWII XXI Bomber Command (20th Air Force) TARGET AERIAL PHOTO MAP CHART was used during the USAAF long-range bombardment operations, against Japan until mid-July 1945. The XXI Bomber Command was headquartered at Harmon Field, Guam, in the Mariana Islands.

Dated May 1945 and titled “SOUTH KYUSHU AREA - CHIRAN AIRFIELD AREA - TARGET NO. 90.38 URBAN”, this A-2 SECTION was produced in limited quantities with previous aerial reconnaissance mission photos by the 3rd Photo Reconnaissance Squadron taken on March 18th, 1945.

This navigators and bombardier aerial photo chart map was specifically creating using the most updated military intelligence in order to give B-29 Superfortress aircraft the most accurate target information. This was done for fast and effective target identification as well as accurate navigation and bomb/incendiary accuracy. These target photo charts were handed to B-29 crews during the target mission briefing and were then carried on the B-29 aircraft to used during the raid itself.

These aerial photo charts were referenced during pre-mission briefings as well as when the bombardier was approaching the target. This was meant to provide the B-29 bombardier with the most real view of his target for the best target identification. The most important primary target buildings were always outlined and marked with a number to be referenced on the target key.

History of XXI Bomber Command B-29 Air Raids on SOUTH KYUSHU AREA - CHIRAN AIRFIELD:

Chiran Air Base, Kyushu was used by Japanese kamikaze pilots to launch planes during Japans Operation Divine Wind to launch planes from mainland japan on suicide missions on USN forces off Okinawa.

The Konan mission was run as a diversion for the last B-29 strikes against Kyushu airfields; on the same day, 11 May, Nimitz released XXI Bomber Command from support of ICEBERG. Arnold immediately reconfirmed current target directives, with the aircraft industry and the principal urban areas as the priority objectives.20 With the two most important engine factories stilled, LeMay chose to concentrate on the great urban areas; his highly successful campaign, already described,* absorbed most of the command's energies from 14 May to 15 June, and except for an abortive mission against the Tachikawa Aircraft Company on 19 May,21 no precision attacks were scheduled until 9 June. The success of the recent strikes, however, had shown that daylight missions could play an important role in an articulated program. In part, the improvement in bombing had resulted from better weather and from better forecasting. Crews had gained confidence from the occasional fighter escort and greater skill with lead-crew training and with combat experience. Finally, there was the change in tactics which had lowered the mean bombing altitude from 30,000 to 20,000 feet and at times sent bomber formations in much lower. This increased the danger both from enemy fighters and flak, but like LeMay's other calculated risks, it paid off in effectiveness without undue cost: of 1,433 B-29's airborne against industrial targets between 24 March and 19 May, only 20, or 1.3 per cent, were lost to all causes.

Japan had entered the war with about 6,000,000 tons of shipping, to which 823,000 were added by seizures during the early conquests. This sizable merchant marine was divided about equally between the army, navy, and civilian pools; the lack of a common control made for inefficient employment, and the failure of a plan to return needed tonnage to civilian use put a continuing burden on Japanese industry, Long-range shipbuilding programs and facilities were grossly inadequate for a major war, and no provision had been made for a convoy system; consequently, Japan was wholly unprepared for the Allied attacks on shipping which began immediately after Pearl Harbor. Even in 1942, sinkings exceeded replacements and thereafter the net losses increased in spite of redoubled efforts in the shipyards (which produced by V-J Day 4,100,000 tons of ships) and in spite of the establishment of convoy routes. Until late in the war, and for the whole of the war, the submarine was the chief killer, but it was ably seconded and made more effective by Navy, AAF, and Marine planes. The steady war of attrition was punctuated by especially heavy losses inflicted during the amphibious campaigns and the great carrier strikes which began in 1944. As early as December 1943 the Japanese started closing down convoy routes; by the following September they had abandoned regular contact with the South and Southwest Pacific and the mandated islands. The Philippines campaign produced a crisis, destroying 1,300,000 tons of shipping and threatening the routes southward to the Indies. The capture of Iwo Jima and the imminent assault upon Okinawa completed the stoppage of regular traffic to the south: harbors on Tokyo and Ise bays became less active and the convoy routes southward from Kyushu to Formosa to Singapore were given up. By March 1945, according to Japanese sources, thirty-five out of forty-seven regular convoy routes had been closed down; an additional burden had been put, where possible, on Japan's inadequate rail system, and traffic between the home islands and the Outer Zone was confined to the Yellow Sea, the Tsushima Strait, and the Sea of Japan. This situation enhanced the importance of ports on the Asiatic side of Kyushu and Honshu and in the Inland Sea, a sheltered natural canal which had long been the vital central link in Japan's transportation system. The southern entrances into the Pacific at either end of Shikoku were no longer used, and the great bulk of Japanese shipping passed through the eastern narrows, Shimonoseki Strait.