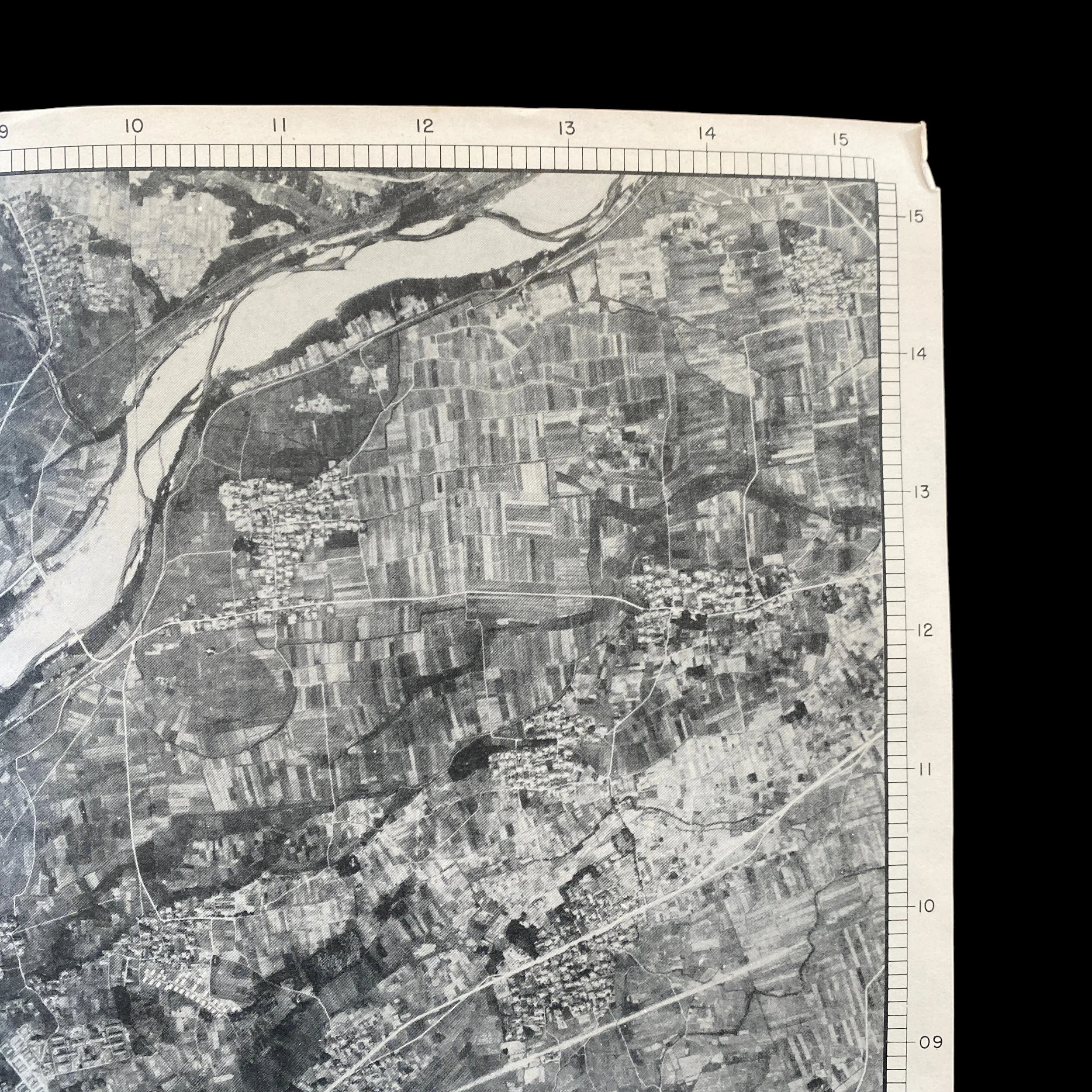

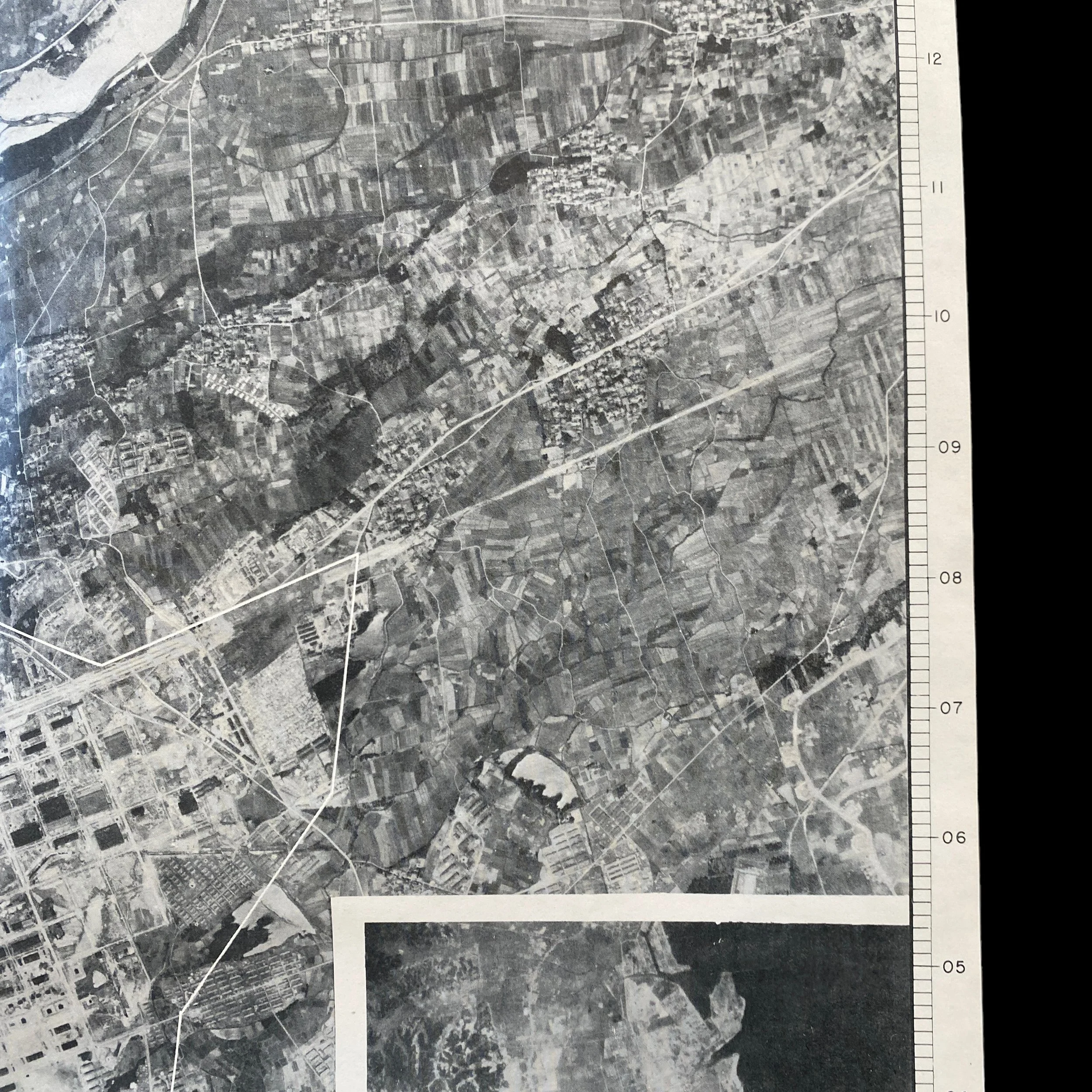

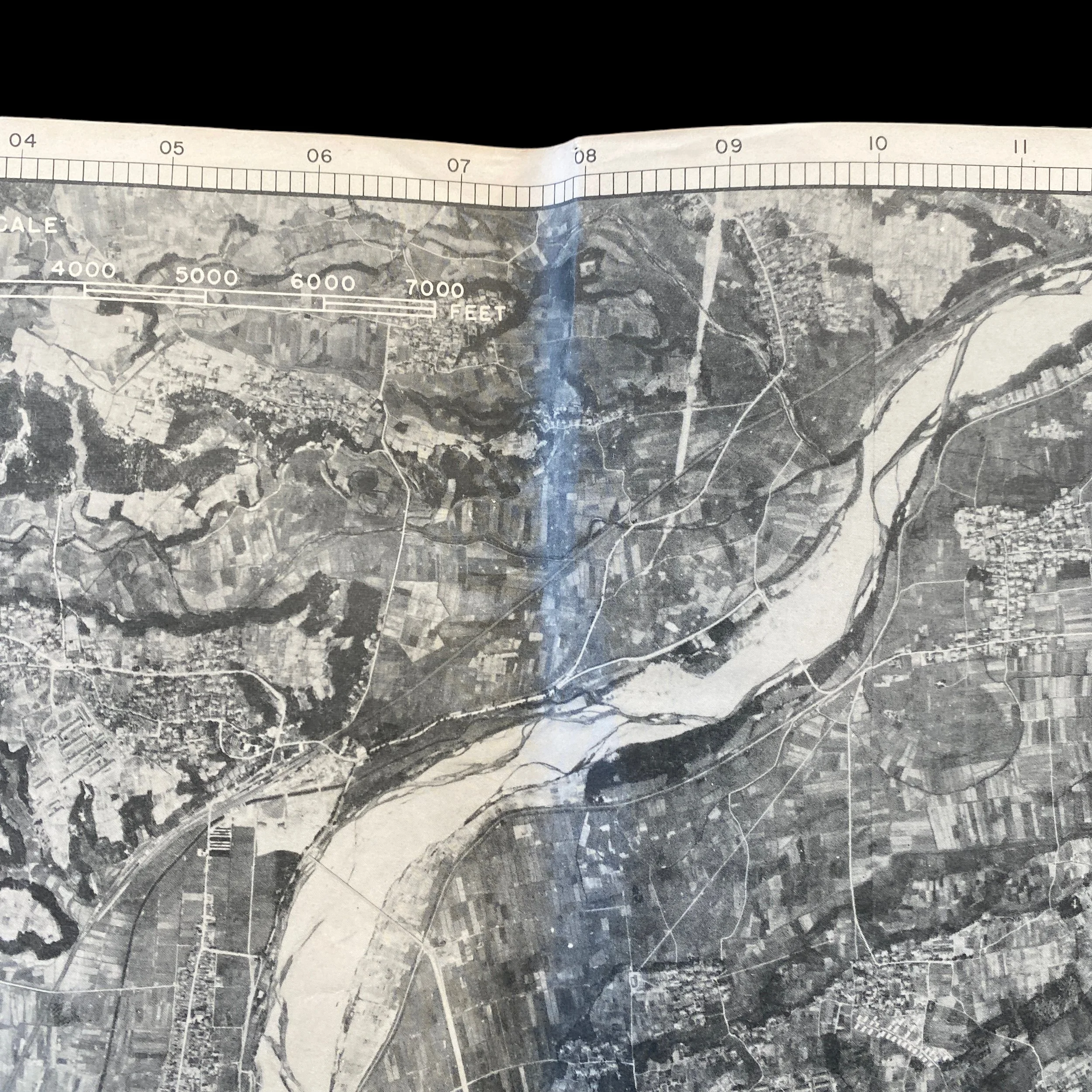

RARE! WWII 1945 B-29 Navigator XXI Bomber Command NAGOYA (SUZUKA NAVAL ARSENAL) JAPAN Target Air Raid Mission Target Photo Map*

RARE! WWII 1945 B-29 Navigator XXI Bomber Command NAGOYA (SUZUKA NAVAL ARSENAL) JAPAN Target Air Raid Mission Target Photo Map*

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

These XXI Bomber Command target photo maps rarely come up for sale in the public sector. This is a once in a timeline chance to own a piece of B-29 WWII history.

Mission #248 - B-29 Air Raid on NAGOYA (SUZUKA NAVAL ARSENAL)

This incredibly scare and museum-grade ‘RESTRICTED’ WWII XXI Bomber Command (20th Air Force) TARGET AERIAL PHOTO MAP CHART was used during the USAAF long-range bombardment operations, against Japan until mid-July 1945. The XXI Bomber Command was headquartered at Harmon Field, Guam, in the Mariana Islands.

Dated July 1945 and titled “NAGOYA (SUZUKA NAVAL ARSENAL) AREA - TARGET NO. 90.20 URBAN”, this A-2 SECTION was produced in limited quantities with previous aerial reconnaissance mission photos by the 3rd Photo Reconnaissance Squadron taken on May 10th, 1945.

This navigators and bombardier aerial photo chart map was specifically creating using the most updated military intelligence in order to give B-29 Superfortress aircraft the most accurate target information. This was done for fast and effective target identification as well as accurate navigation and bomb/incendiary accuracy. These target photo charts were handed to B-29 crews during the target mission briefing and were then carried on the B-29 aircraft to used during the raid itself.

These aerial photo charts were referenced during pre-mission briefings as well as when the bombardier was approaching the target. This was meant to provide the B-29 bombardier with the most real view of his target for the best target identification. The most important primary target buildings were always outlined and marked with a number to be referenced on the target key.

History of XXI Bomber Command B-29 Air Raids on NAGOYA (SUZUKA NAVAL ARSENAL):

The weather had held up somewhat better than had been expected, allowing five daylight missions in April, three in May, four in June. Thereafter almost a month passed before visual conditions again obtained. On 24 July the command put up 625 planes, directed against 7 targets in the Nagoya and Osaka areas. The attacks were coordinated with a two-day carrier strike in the Inland Sea region. Targets for the B-29's were chosen to give the several formations a wide choice according to local conditions, but in each case the force assigned was considered heavy enough to destroy its primary target.35 Weather turned out spotty; 26 aircraft dropped 166 tons on targets of opportunity and 573 dropped 3,539 tons on primary visual or radar targets.36 The Sumitoma Metal Company's propeller factory, whence most of the machine tools had been removed, was completely wrecked.37 Kawanishi's Takarazuka plant lost most of its buildings and no effort was made subsequently to repair them.38 The Osaka arsenal, though cloud-covered and attacked by only part of the assigned force, suffered additional damage amounting to 10 per cent of the original roof area.39 Aichi at Eitoku sustained its heaviest damage of the war, damage which was superfluous because of previous dispersal.40 Nakajima at Handa, struck for the first time, lost its principal assembly buildings, but the attack came too late in the war to have much direct effect on production.

LeMay's operational plan, as he described it in a directive to the 313th Wing on 2 3 January, was conceived as a four-phase program: 1) 15 February to 15 March, training; 2) 16 to 31 March, partial blockade with standard mines; 3) 1 April to 31 May, complete blockade with new-type mines; and 4) 1 June and after, "further mining."102 His target list, based on Navy studies, was in the following order of priorities: Shimonoseki, Bisan Seto, Kobe-Osaka, Hiroshima-Kure, Sasebo, Nagasaki, Nagoya, Tokyo-Yokohama, Yokosuka, Tokuyama, and Shimizu.103 This program Arnold approved, but Norstad made it clear that the commitment to mining was an experimental one which should not be allowed to interfere with established bombardment policies, as some in Washington feared might happen.104 In spite of these misgivings in Arnold's headquarters, LeMay went on with his preparations and on 11 March ordered the 313th Wing to execute its first two mining missions, coded appropriately STARVATION I and II, between 22 and 27 March; later the dates were postponed to between 27 March and 1 April.105 The target was the Shimonoseki Strait, always an important thoroughfare but at the end of March, for reasons that may be described briefly, certainly the most important shipping center in the Empire.

LeMay's directive of 18 April called for repeat missions to Shimonoseki, for blockading completely the approaches to Kobe and Osaka, and for laying only attrition fields at Tokyo, Yokohama, and Nagoya harbors. The latter objectives reflected an appreciation of current traffic patterns which has been validated by Japanese statistics made available after the war. Kobe and Osaka, at the eastern end of the Inland Sea, constituted together a shipping area second only to Shimonoseki Strait; the other ports, opening on the Pacific, had declined to where they were not worth an intensive campaign. Expressed in terms of the monthly average in the peak year 1942, tonnage handled in March 1945 was as follows: Kobe, 71.7 per cent; Osaka, 48.1; Yokohama, 11.6; Nagoya, 4.7; Tokyo, 2.3.114

The missions were not run until early May when the strikes in support of ICEBERG were tapering off. On the 3d, 88 B-29's sowed 668 mines, with good patterns in the Kobe-Osaka area and Shimonoseki's Minefield L; on the other side of the strait, where only 17 of 30 planes assigned were able to attack, the field was not a tight one. On this mission the new A-6 pressure mechanism was used for the first time, and when a string of mines equipped with it fell into shallow water, the device was considered compromised.115 On 5 May, eighty-six B-29's planted mines in eight fields. At Tokuyama, Aki-nada, Bingo-nada, and Shodo-shima-Bisan Seto, the patterns were good, but at four port areas--Nagoya, Kobe-Osaka, Hiroshima-Kure, and Tokyo--results were less satisfactory.116

The Japanese city of Kobe was attacked by 331 B-29s on the night of March 16/17, 1945, with a resulting firestorm that destroyed roughly half its area, killing 8,000 and leaving 650,000 homeless. On May 13, 1945, a fleet of 472 B-29s struck Nagoya by day, followed by a second raid at night on May 16 by 457 B-29s. The two raids on Nagoya killed 3,866 Japanese and rendered another 472,701 homeless. A daylight incendiary attack on Yokohama on May 29 sent 517 B-29s to that city escorted by 101 P-51s fighter planes. This force was intercepted by Japanese Zero fighters, sparking an intense air battle in which five B-29s were shot down and another 175 damaged. The 454 B-29s that reached Yokohama struck the city’s main business district and destroyed 6.9 square miles of buildings with more than 1,000 Japanese killed.

In “The Fog of War” film, one of Robert McNamara’s “lessons” comes about midway in the film – Lesson No.5, that “proportionality should be a guideline in war.” And for this lesson, McNamara draws on the LeMay firebombing campaign, offered in the film clip below. In the clip, McNamara describes the firebombing of Tokyo and other cities, listing the percent of each Japanese city destroyed and naming similar-sized U.S. cities for comparison purposes: Tokyo, roughly the size of New York City, was 51% destroyed; Toyama, the size of Chattanooga, 99% destroyed; Nagoya, the size of Los Angeles, 40% destroyed; Osaka, the size of Chicago, 35% destroyed; Kobe, the size of Baltimore, 55% destroyed, and others. And as he concludes, McNamara emphasizes this was all before the nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nagoya, Japan / 40% destroyed by air raids.