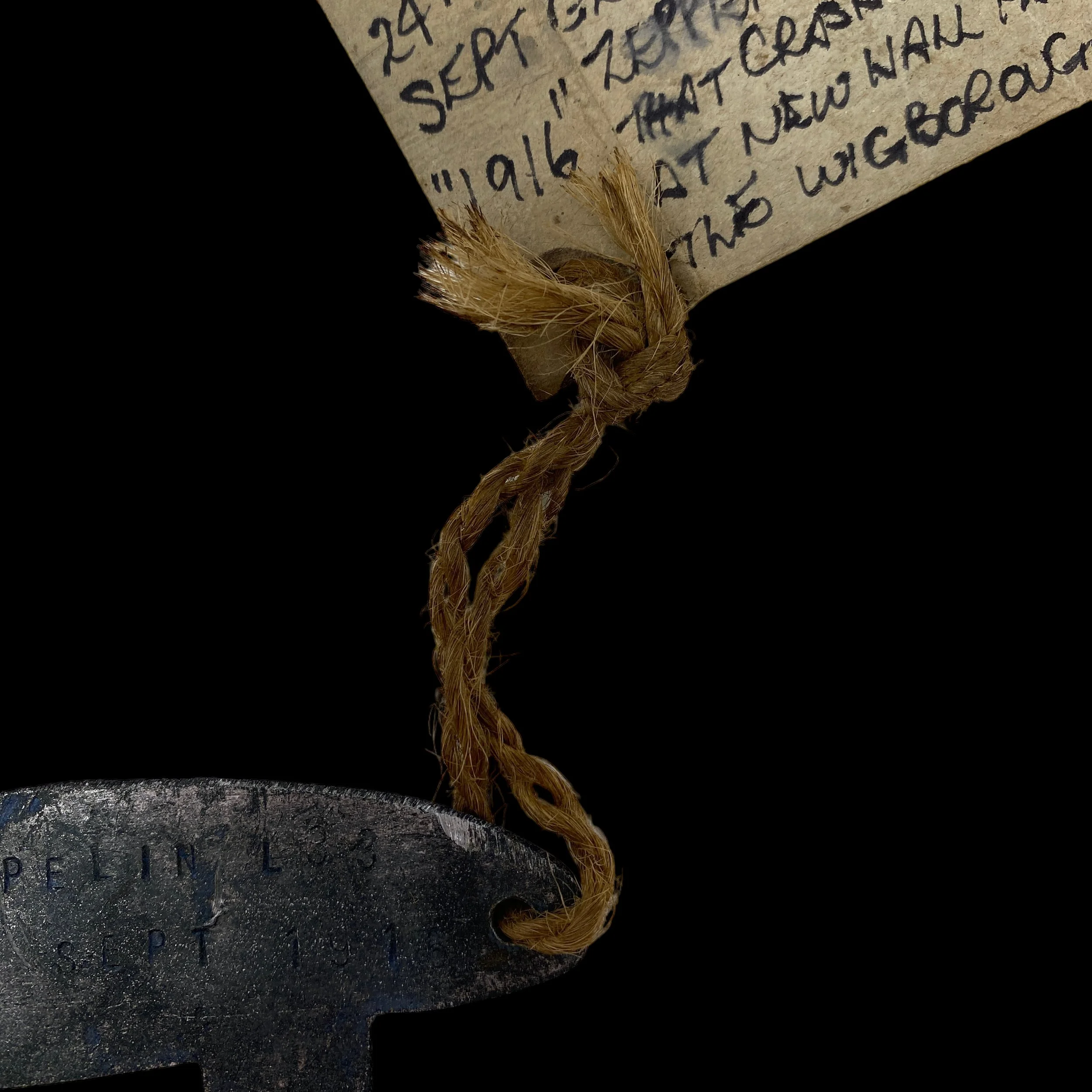

VERY RARE! WWI September 1916 German Zeppelin L33 Autumn Offensive "LONDON RAID" Shot Down Wreckage Relic

VERY RARE! WWI September 1916 German Zeppelin L33 Autumn Offensive "LONDON RAID" Shot Down Wreckage Relic

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

“The third raiding period began when 12 navy airships headed for Britain late in the afternoon of September 23. The navy crews had been dismayed by the destruction of SL-11 three weeks previously, but that had been a wooden army ship. Certainly such a thing could not happen to the veteran navy captains in their true Zeppelin airships. The new L-30 class ships, led by Heinrich Mathy in the L-31, worked their way southward and crossed the southern English coast. This route assured a strong tail-wind and speedy flight past the most dangerous anti-aircraft areas over London. The other smaller Navy ships; L-13, L-14, L-16, L-17, L-21, L-22 and L-23 took the direct route into the Midlands, with only the L-17 causing any casualties at Nottingham. Captain Alois Böcker in the L-33 was the first to arrive over the capital. He dropped most of his bomb-load on the East End around Bow and Stratford, with the airship crew reporting visible fires and explosions with each bomb burst . However a shell from the defenses over Bromley exploded inside the ship, causing tremendous physical damage but no fires. She dropped much of her water ballast which was reported by British ground spotters as a smoke screen, and made her way eastward losing 800 feet of altitude each minute. After a dangerous encounter with a British airplane which pumped several drums of Brock-Pomeroy ammunition into L-33 to no effect, the airship came to earth at Essex where Böcker and his men jumped to the ground and fired several flares into her. They were promptly captured as L-33 burned to the ground having landed mostly intact.”

This incredibly rare and museum-grade WWI artifact is an original wreckage fragment of the infamous German Zeppelin L33 that was shot down on the night of 24 September 1916, following an aerial raid attack on London. German Zepplin L33 was apart of the German Autumn Offensive in 1916. The Autumn Offensive was poised to create havoc and devastation across England and London.

Crashing near the small village of Little Wigborough the airship had been on a bombing raid over London and was returning to Germany. She was, however, hit by gunfire over the East End and she then struggled to stay aloft. Losing height over Mersea Island, L33 came to earth straddling the lane to Little Wigborough Church and only a few yards from New Hall Cottages. The German Zepplin L33 crew all escaped from the airship and the German Captain, Aloys Bocker, went to the cottages to warn them that he was about to set the airship on fire. They were somewhat terrified and did not answer the door - but occupants and cottages all survived the resulting inferno. Captain Bocker then marched his crew along the lane - until they were met by Special Constable Edgar Nicholas. The German crew surrendered. Edgar Nichols was soon joined by Special Constable Elijah Trailer and then by Police Sergeant Ernest Edwards who was on leave, staying in the lane. The crew were marched to Peldon Post Office and then on to Mersea Island. The Military met them at the Strood and took over.

The loss of both L-32 and L-33 had a serious negative effect on morale. The crash of an army airship was one thing, but the loss of two veteran navy captains, their crews and their new ships was altogether different. The next raid, just two nights later was far more cautious. Captain Ganzel of the L-23 was dismissed after the raid due to his erratic behavior. His nerves were wrecked and he was transferred to surface fleet duty. Horst von Buttlar in the L-30 made a cautious approach near the English coast at Cromer, dropped his bombs in the sea and turned back. Mathy in L-31 made an audacious attack on Portsmouth, a previously untouched target. Unfortunately for him, the searchlight defenses were very strong and he mistakenly dropped his bombs into the harbor instead of on the Navy yard. The British, who knew from intercepts that it was Mathy were so astonished at not being accurately bombed that they thought it must have been a reconnaissance flight; a tribute to their personal opinion of Mathy.

The End of Zeppelin L33: THE END OF ZEPPELIN L33 (The Authentic account):

Zeppelin L33 was commanded by Kapitan - Leutenant Bocker.

During the daylight hours of Saturday September 23rd. 1916 the weather was ideally suited for an airship attack on London.

Three zeppelins, the L31, L32 and L33 were directed to the area North East of the capital.

The L33 was fired upon by a British Naval Vessel as she approached the British coast near Foulness. This defensive action was unsuccessful however and L33 continued on course.

About 10.4Opm L33 dropped incendiary flares over Upminster and bombs were dropped on Sutton's Farm Aerodrome, Hornchurch.

The attack continued for over an hour and was continued in a zig-zag pattern over Woolwich and West Ham.

It is generally agreed that this attack resulted in 11 persons being killed and 25 injured. The attack was not of course received passively. A considerable barrage of anti-aircraft fire was directed at L33 which resulted in several of her gas bags being punctured and a propeller being damaged.

Shortly after midnight L33 turned to the East and attempted a run for the coast as she was now losing gas at an alarming rate. While over Kelvedon common L33 was again fired upon and Bocker was obliged to order all the water ballast to be discharged in an attempt to gain height. Just West of Chelmsford L33 was attacked by a B.E.2c aeroplane piloted by 2nd. Lieutenant Alfred Brandon. Brandon zoomed in tor the attack only to have his Lewis gun leap out of its mounting and nearly falling overboard. He managed to re-establish his gun and continued his attack until a gun malfunction and temporary engine failure forced him to disengage.

Bocker and his crew were by now desperately worried by the amount of gas lost and all loose equipment was ordered to be jettisoned. (There is also an unconfirmed report that an unpopular crew member was threatened with an early quick descent.)

The residents of Broomfield were surprised to find metal bars and tools in their gardens. The villagers of Boreham were the fortunate recipients of a machine gun. All this action did not stop the craft sinking however and this resulted in both Wickham Bishops and Tiptree each receiving a machine gun.

About 1.15am Bocker identified the estuary at West Mersea almost by dangling his foot in it by now and it was obvious that he would never be able to reach his home base. Bocker unloaded his remaining bombs into the sea and then turned back inland towards Mersea.

The L33 crash landed just South of Wigborough Church coming to rest across two two fields and completely blocking the lane to the church.

Bocker was aware that, although damaged, his Zeppelin would be a rich prize indeed for the British. Accordingly he arranged for the craft to be burned. Before firing his flare pistol into the hydrogen filled Zeppelin, Bocker knocked on the door of a nearby cottage in order to evacuate the residents in view of the likelihood of a gigantic explosion. The occupants were however too scared to open the door to a party of German soldiers and remained inside.

The explosion of the airship was heard several miles away but fortunately there was only one slight casualty, a small dog which was tied to its kennel at the cottage had its hair singed.

Bocker then collected his crew together and commenced to march them towards Colchester.

Having travelled about half a mile they were met by Special Constable Edgar Nicholas, who, having heard the explosion, was on his way to investigate.

Nicholas ignored Booker's request to be taken to Colchester and started to march them towards Peldon. On the way they were met by Sergeant Edwards of the Metropolitan Police. Sergeant Edwards was in fact on leave from duty and lived nearby.

Together the two Policemen continued to march the commander and his crew towards Peldon.

Anticipating the need for reinforcements PC Charles Smith of Peldon had made his way to Peldon Post Office on hearing the Zeppelin explode and was attempting to put a call inrough to his superiors for instructions when the crew of the airship arrived. After some little time it became apparent that PC Smith was going to be unable to contact anyone else for help and attempts to call up a military unit at West Mersea were unsuccessful.

Alfred Wright then volounteered to ride off on his motorcycle to fetch help. He set off but regrettably was involved in a collision with another vehicle shortly after leaving the post office. Mr Wright broke both legs in this accident and died from his injuries two months later. The wreckage of the Zeppelin had to be cut through to allow his funeral to reach the church.

Eventually PC Smith was able to get a call through and was instructed to march the captured crew to the Strood at Mersea where he would be met by a Military escort.

This he did, unarmed, and with the help of a few special constables who had by now arrived on the scene.

For his coolness and judgement in dealing with this matter PC Smith was awarded the medal of merit and promoted to Sergeant with immediate effect by the Chief Constable.

The wreckage of the airship drew thousands of visitors in the following weeks and a sum in the region of £80.00 was collected from them in donations. This money was given to the Red Cross.

German Zeppelins During WWI:

At the start of World War One, lighter-than-air technology was older than other aviation technologies of the time and it showed much promise. The airships built by the Zeppelin Company in Germany were gigantic machines by the standards of the day, and they were seen as tangible fruits of the inevitable march of progress. An airship had graceful lines, enormous size, and a characteristic sound; the drone of their great multiple propellers beating the air. People seeing them were caught in a spell, so impressive was the very sight of a zeppelin. The heavier-than-air aircraft of the day were still rather flimsy machines, barely strong enough to carry one or two people. It is no surprise then, that these lighter-than-air vessels capable of lifting several tons were seen as the wave of the future for aviation.

As the war progressed, the German navy and army each built their own mutually exclusive airship fleets. The navy zeppelins however, were usually of aluminum Zeppelin Company manufacture, whereas the Army often used the wooden Shutte-Lanz or "SL" ships rejected by the Navy due to their excessive weight. Both services began conducting bombing missions over England, believing that aerial bombing would ultimately destroy that country's industrial base. This overconfidence in the effectiveness of turn-of-the-century high explosives paralleled similar beliefs in most military circles at the time. It all combined into a powerful sensation that the awe inspiring airships could never fail in whatever task they chose. For the first year, it seemed they might be right. German airships ranged over England impeded only by the weather. Flying heavier-than-air biplanes at night was a still a very dangerous practice and the few planes able to find the airships could do little more than put a few small holes in them.

By 1916, there were two generations of German airships employed in combat. The L-13 through L-24 were older ships, which made up the majority of any attack force. The newest ships were the L-30's, of which five had been built; the L-30, L-31, L-32, L-33 and L-34. High hopes were pinned on these latest vessels. They were far larger than the previous generation of zeppelin, with a hydrogen capacity of 1,589,000 cubic feet, which gave them a much greater bomb payload. They were however, only marginally faster and could climb no higher than their predecessors, something not considered necessary at the time. No attempt was made to anticipate the British reaction to being bombed with impunity. Since all past methods of destroying zeppelins involved shooting them full of holes, increased lifting capacity was considered to be an adequate solution. It would soon be discovered however, that Great Britain had found a way to ignite the flammable hydrogen gas which gave all zeppelins their lifting power.

In the summer of 1916, three new types of British machine gun ammunition which had been under development for years became available for general use. Two types, named "Pomeroy" and "Brock," after their inventors, were explosive bullets. The third, called "Buckingham", was a phosphorus incendiary bullet. Any one of these bullets was only marginally effective when fired at a zeppelin, but when mixed they formed a lethal combination. The explosive rounds blew holes in the zeppelin's gas cells, allowing the hydrogen to escape and mix with oxygen to form an explosive mixture. The incendiary bullets then ignited the mixed gases. This new mixed ammunition package was to become Great Britain's wonder weapon against airships

Autumn Offensive:

In the summer of 1916, the new L-30 class ships were delivered to the German Navy and the leader of airships, Peter Strasser, planned an all out offensive against England. He was determined to show once and for all that the zeppelin fleet could pour enough explosives onto targets in England to make a material difference in the war. There was no doubt as to their morale benefits, the German people loved the zeppelin fleet and each raid was greeted with the greatest fanfare throughout Germany. However the British population was seething with anger; when one airship crashed at sea a civilian British trawler nearby violated the code of the ocean by not rescuing the airship's crew, standing by to watch them drown instead.

Three raids were carried out during the first raiding period in the Autumn and Summer of 1916. On July 31, August 2 and August 8, Navy airships arrived over Britain during late evening and returned to German airspace by morning. These raids were uneventful both in the amount of damage caused to ground targets or airships. As in many previous missions, the airships continued to overestimate the damage they inflicted, often not realizing that their bombs were dropping into the sea. However, they also suffered little or no damage from the still ineffective British air defenses.

The second raiding period began with another marginally effective raid on August 24, followed on September 2 by the largest zeppelin raid of the war. Late on the afternoon of that day, 12 Navy airships; L-11, L-13, L-14, L-16, L-17, L-21, L-22, L-23, L-24, L-30, L-32 and SL-8 were all sent into the air. For once, army ships were also to attack the same night. Four Army airships: LZ-90, LZ-97, LZ-98 and the SL-11 took off from their bases and headed for England. The sixteen ships carried a total of 32 tons of bombs.

LZ-98, commanded by Ernest Lehmann, future commander of the airship Hindenburg, approached from the southeast arriving over the Thames River at Gravesend. Believing that he was over the London dockyards he dropped his bombs and made off to the northeast, briefly encountering a British aircraft piloted by Second Lieutenant William Robinson before escaping into the clouds.

The third raiding period began when 12 navy airships headed for Britain late in the afternoon of September 23. The navy crews had been dismayed by the destruction of SL-11 three weeks previously, but that had been a wooden army ship. Certainly such a thing could not happen to the veteran navy captains in their true Zeppelin airships. The new L-30 class ships, led by Heinrich Mathy in the L-31, worked their way southward and crossed the southern English coast. This route assured a strong tail-wind and speedy flight past the most dangerous anti-aircraft areas over London. The other smaller Navy ships; L-13, L-14, L-16, L-17, L-21, L-22 and L-23 took the direct route into the Midlands, with only the L-17 causing any casualties at Nottingham. Captain Alois Böcker in the L-33 was the first to arrive over the capital. He dropped most of his bomb-load on the East End around Bow and Stratford, with the airship crew reporting visible fires and explosions with each bomb burst . However a shell from the defenses over Bromley exploded inside the ship, causing tremendous physical damage but no fires. She dropped much of her water ballast which was reported by British ground spotters as a smoke screen, and made her way eastward losing 800 feet of altitude each minute. After a dangerous encounter with a British airplane which pumped several drums of Brock-Pomeroy ammunition into L-33 to no effect, the airship came to earth at Essex where Böcker and his men jumped to the ground and fired several flares into her. They were promptly captured as L-33 burned to the ground having landed mostly intact.

Mathy in L-31 arrived an hour after Böcker. At 12:15 A.M. he reported seeing an airship (it was indeed Böcker in L-33) to the east with large fires burning on the ground in her wake. He followed a course over Streatham, Brixton and Kennington, dropping most of his bomb load on the highway running through there. He then made his escape over northern London at maximum speed. At 1:15 a.m., Mathy saw another airship over what he thought was Woolwich. It was Captain Werner Peterson in the L-32, which burst into flames and crashed to earth as Mathy and his crew looked on. Mathy's report on the event was terse but there was no doubting its traumatic effect on the crew.

L-32 had come onshore after circling for about an hour. Peterson's last radio message received was garbled, but it is possible that L-32 had engine trouble and circled until repairs were made. Up to that point he and Mathy's ship had been cruising together. When L-32 broke out of the cloud cover over the Thames River she was spotted almost immediately and pinned in the searchlight beams of the city's eastern defenses. Peterson may have realized his danger because L-32 dropped her bombs in rapid succession and turned toward the sea while attempting to gain altitude. First Lieutenant Frederick Sowery was in the air that night and nosed his British built BE2c 4112 biplane toward the zeppelin which was so dazzlingly illuminated by the searchlights. After firing two drums of Brock-Pomeroy ammunition at the airship, he made a third pass, firing into the side of the zeppelin until he saw flames on its outer fabric. L-32 quickly caught fire and with her hydrogen burning off like a blowtorch she dropped slowly to the ground near Snail's Hall farm, Billericay, killing all on board. After "firing" the zeppelin, Sowery dropped a red verys light (flare) and then landed at Sutton's farm. Officers of the Naval Intelligence Division were first on the scene and despite the heat, they raced through as much of the wreckage as possible (seen at left). They were rewarded with a copy of the German Navy cipher book, which Peterson had allowed on board the L-32 against regulations. It will never be known why he allowed it, if he even knew that it was on board. Its capture was a boon to the Royal Navy code breakers.

The loss of both L-32 and L-33 had a serious negative effect on morale. The crash of an army airship was one thing, but the loss of two veteran navy captains, their crews and their new ships was altogether different. The next raid, just two nights later was far more cautious. Captain Ganzel of the L-23 was dismissed after the raid due to his erratic behavior. His nerves were wrecked and he was transferred to surface fleet duty. Horst von Buttlar in the L-30 made a cautious approach near the English coast at Cromer, dropped his bombs in the sea and turned back. Mathy in L-31 made an audacious attack on Portsmouth, a previously untouched target. Unfortunately for him, the searchlight defenses were very strong and he mistakenly dropped his bombs into the harbor instead of on the Navy yard. The British, who knew from intercepts that it was Mathy were so astonished at not being accurately bombed that they thought it must have been a reconnaissance flight; a tribute to their personal opinion of Mathy.