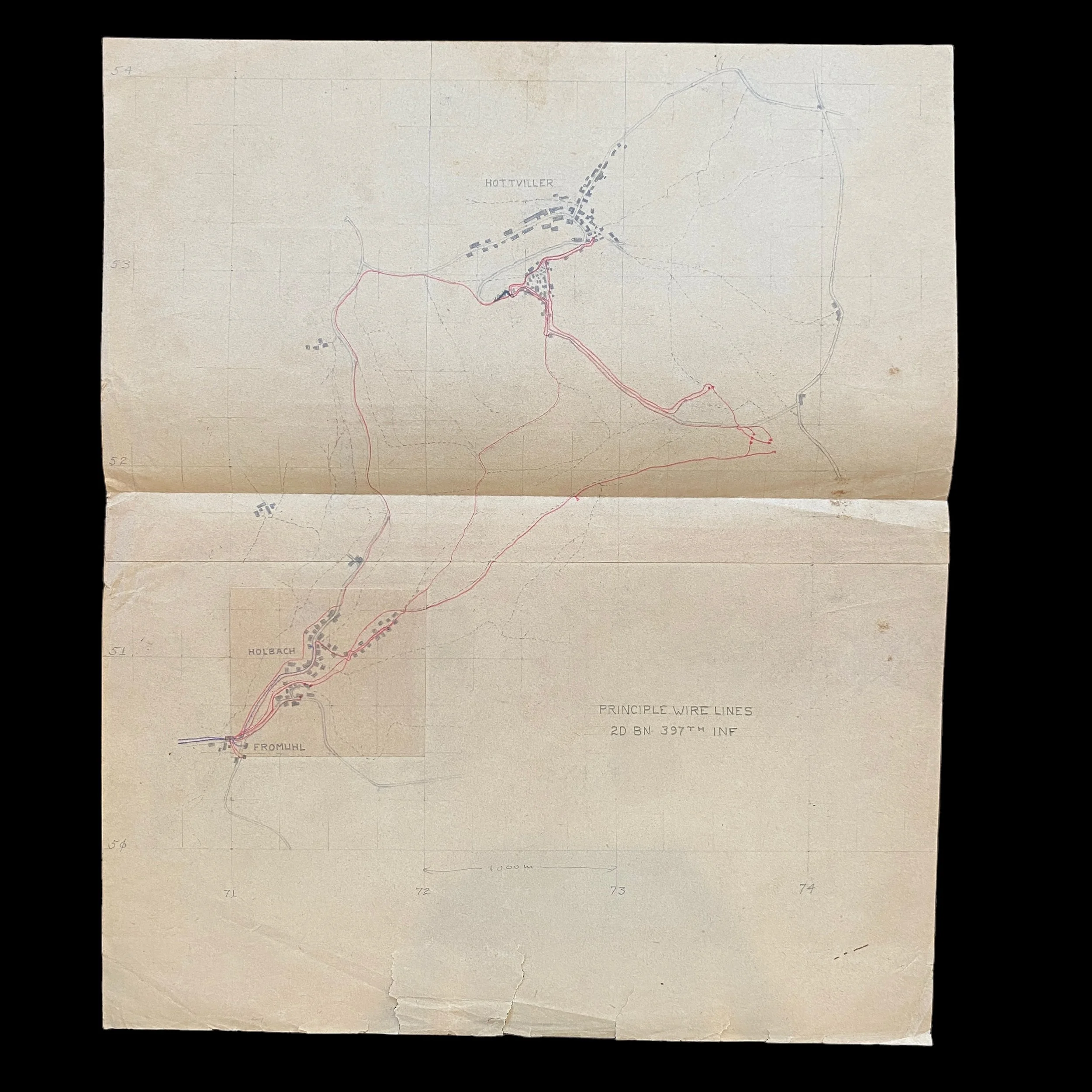

VERY RARE! WWII Operation Undertone 397th Infantry Regiment 100th Infantry Division Hand-Drawn "PRINCIPLE WIRE LINES” Front-Line Communication Map

VERY RARE! WWII Operation Undertone 397th Infantry Regiment 100th Infantry Division Hand-Drawn "PRINCIPLE WIRE LINES” Front-Line Communication Map

Comes with C.O.A.

*The entire division hit the line again Dec. 3 with one of the toughest missions any division had been assigned. Relieving the 44th Inf. Div. of part of its sector, the 100th was to drive northeast and breach the Maginot Line near Bitche, the heart of the entire fortifications system.

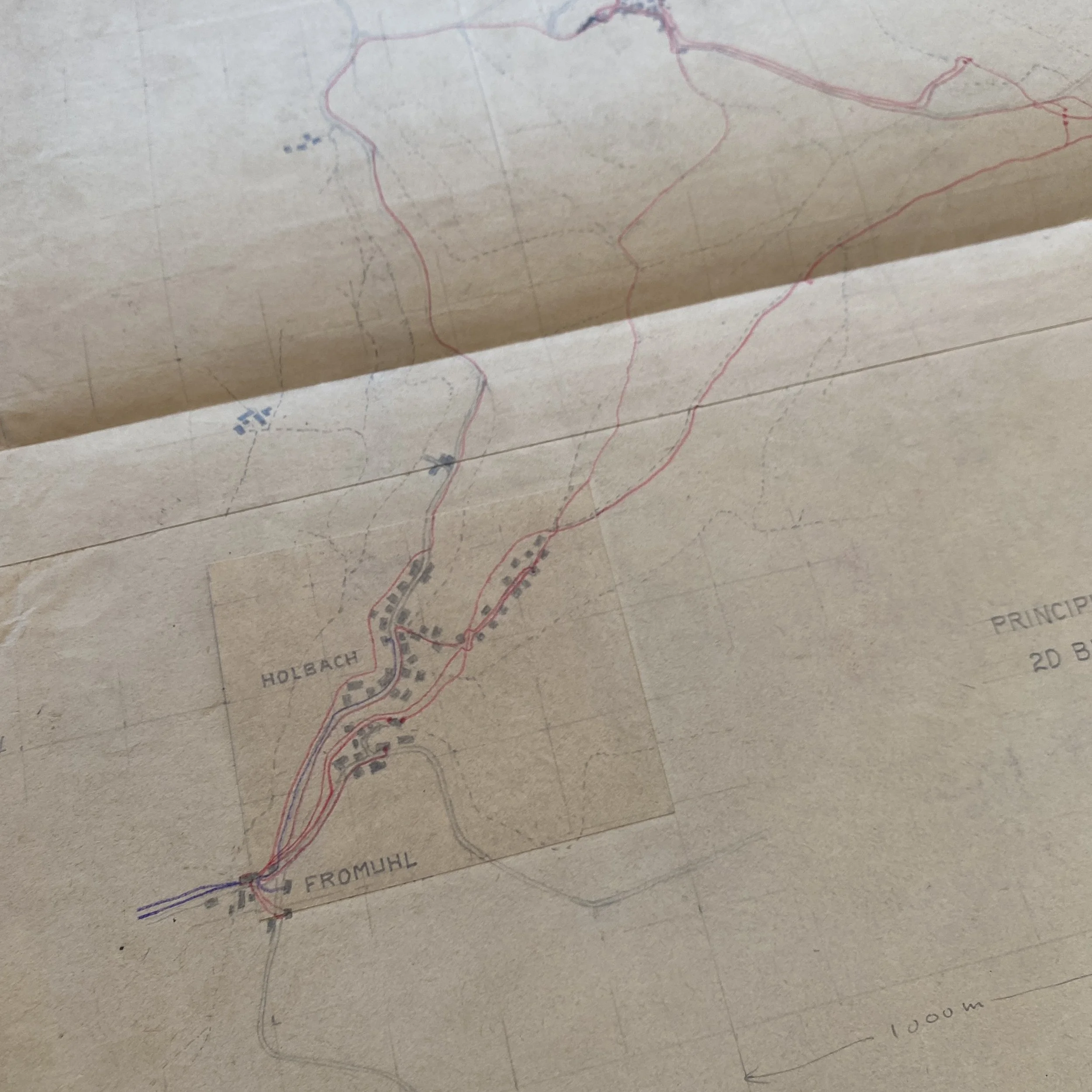

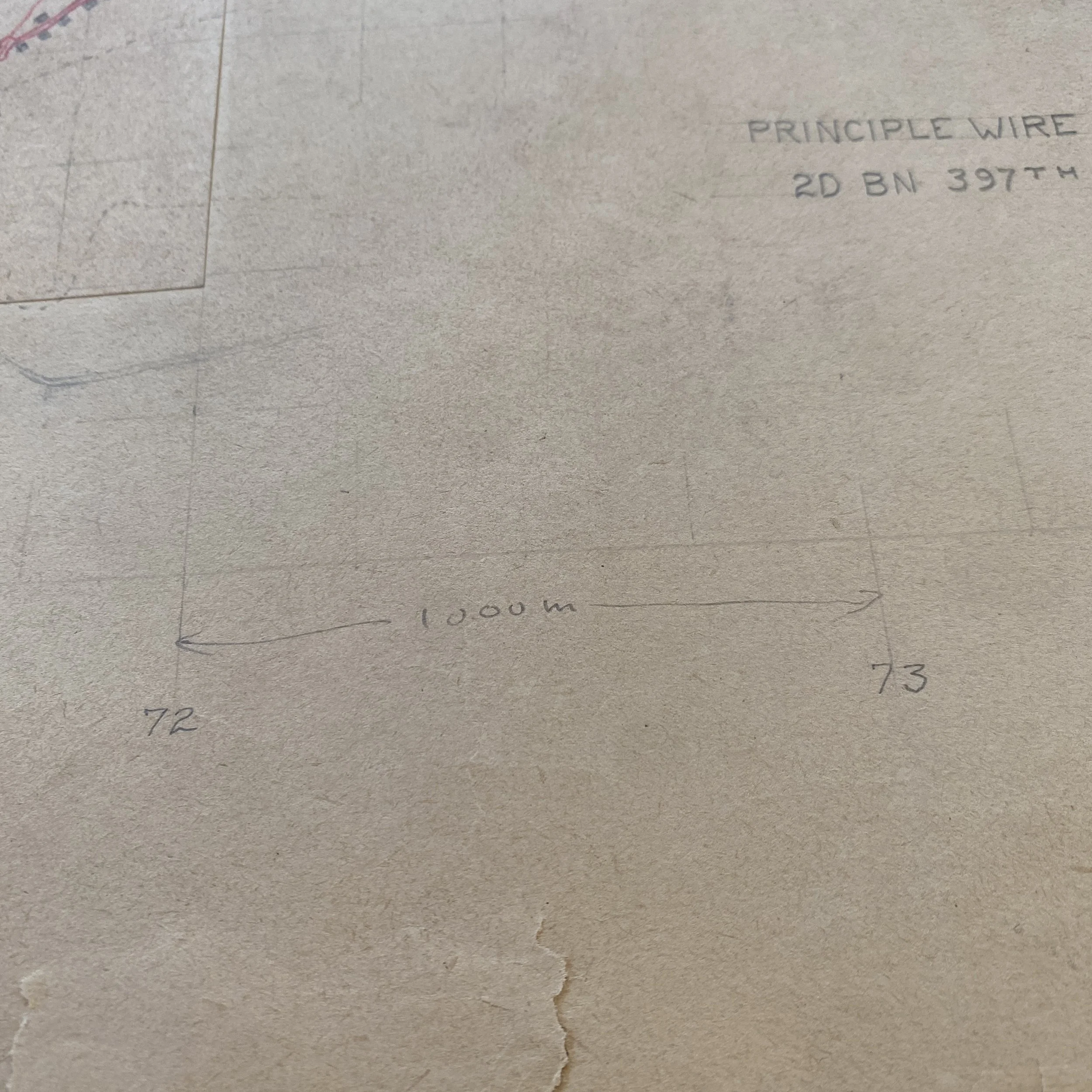

This incredibly rare and museum-grade WWII hand-drawn Rhineland Campaign combat map was used by the 2nd Battalion - 397th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division as Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third Army and U.S. Infantry and Armored Divisions advanced from France into Belgium and Germany.

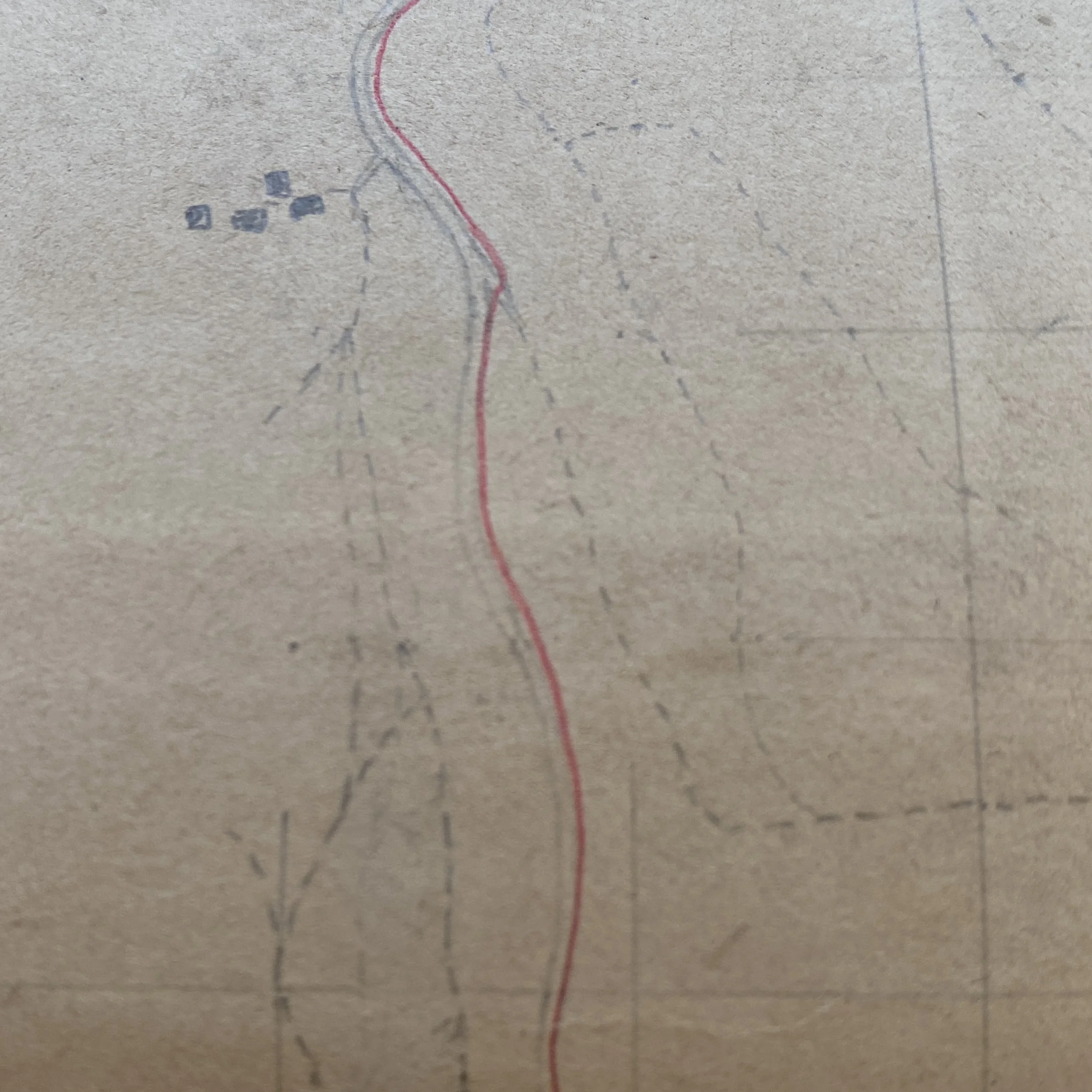

This extremely rare hand-drawn combat map shows the “PRINCIPLE WIRE LINES” that were used for effective combat communication on the front line of advancing U.S. Infantry and Armored Divisions.

This map shows the towns of FROMUHL, HOLBACH, & HOTTVILLER (located four miles northwest of Bitche) as Patton’s Third Army made their advance during Operation Undertone.

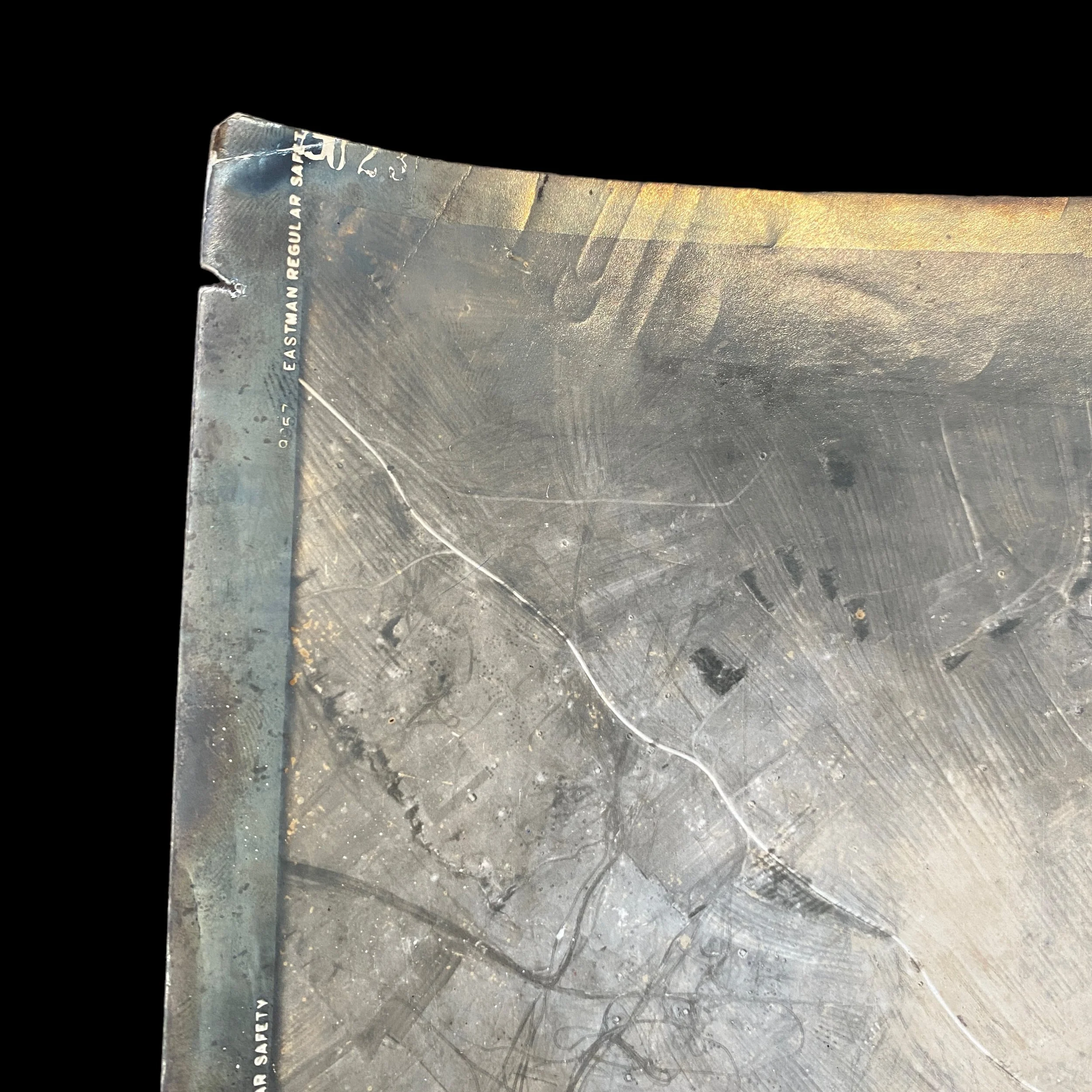

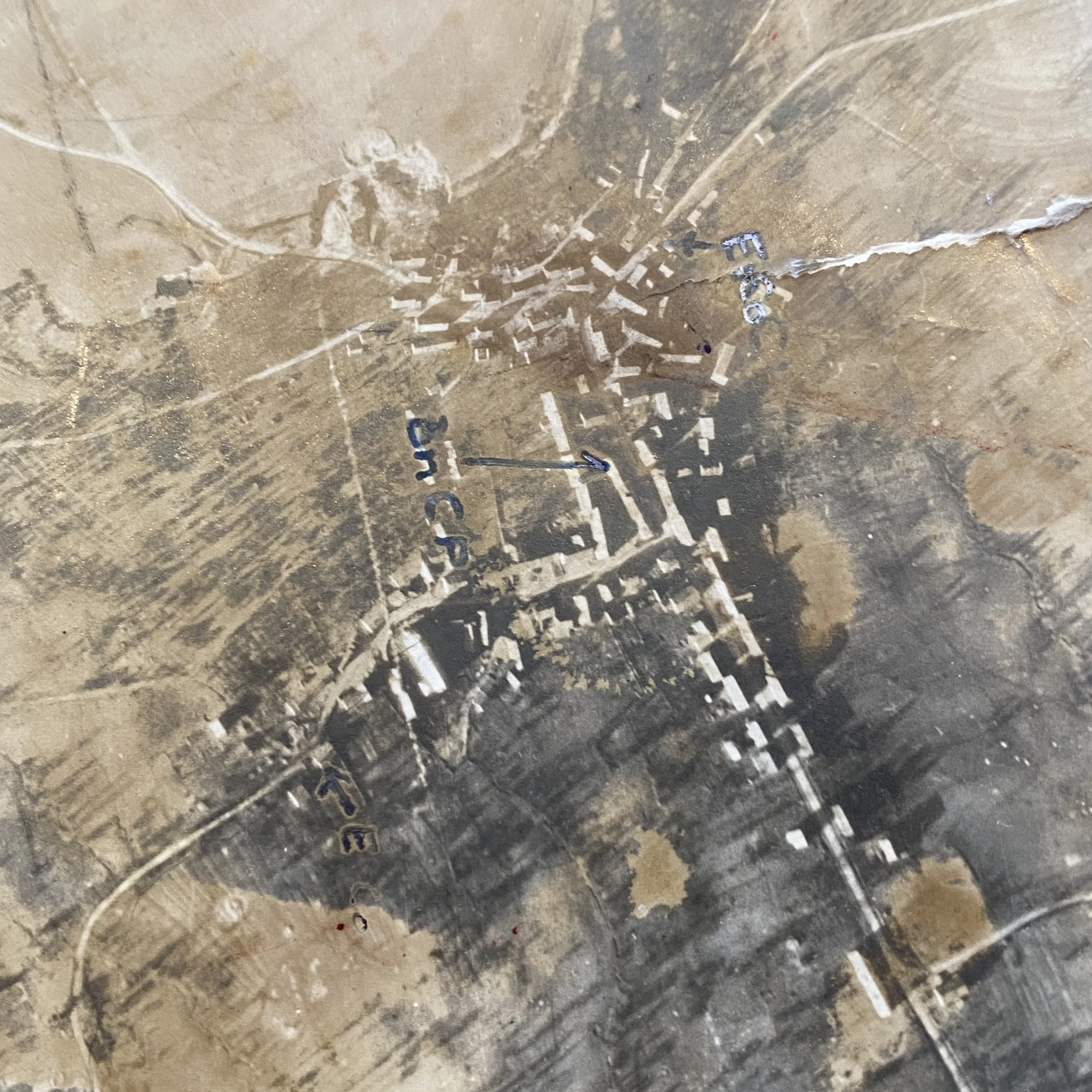

This map also comes with a hand-marked combat used aerial intelligence photo that was used to make this specific map by the 397th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division soldier. This is an incredible historical pairing.

***Except taken from a U.S. soldier of the 397th Infantry Regiment as they were in the area shown on this map:

“The strength of unit continued to diminish, as men were wounded or killed, and many became ill. Our platoon had started out at full strength of 40 men, but by the end of November, we were reduced to fewer than 20 men. I remember a night when the company was told to send its strongest platoon to hold a road junction. Our platoon was chosen and we were only 14 men. One soon came to the conclusion that the probability of escaping injury or death was decreasing each passing day. Early in December, we were moved north somewhat, and committed in the vicinity of Ingwiller. The Division’s ultimate objective was the fortress city of Bitche, a part of the Maginot Line, but we had some ground to take before we would reach that objective. About December 8 and 9, we engaged in heavy battle with the Germans. I remember that we were to take a road junction. The Germans occupied the position and had armored cars with 20mm cannon. As we advanced toward their position, they would spray the forest with 20mm cannon fire, which exploded on impact, scattering small fragments everywhere. Several of our men were wounded. Jimmie Pierce, a member of our platoon, caught a round in his hand that failed to explode and he had to go to the aid station with the unexploded round in his hand. I never heard the outcome of that. Jim never came back to the platoon as far as I remember. The Germans then began to shell us with mortar fire. I found an abandoned German foxhole and took refuge in that. We could hear the mortars fire and then in a few minutes the rounds would be falling in on us. It caused a panic among the troops, and soon everyone was running toward the rear. I followed after, but as I was carrying a BAR (Browning automatic rifle) and a heavy load of ammunition, I had trouble keeping up. Finally, I just had to rest, so I hid behind a log and waited to see if the Germans would follow. Fortunately, they didn’t. We lost many wounded that day, and some were killed. When we finally reassembled for the night, and a head count was taken, it was apparent that some men were still up on the ridge. The CO organized patrols to go up on the ridge to bring down the wounded. I didn’t go, because I was exhausted and felt I would be more of a liability than a help. The next day we resumed the attack, but with better success. We continued to press on toward our objective. The days became a blur to me, with each day much like the day before. We were constantly in danger of small arms and mortar fire, and now the weather was also becoming an enemy. I had seen several of my comrades develop trench foot due to the constant cold and wet foot gear. I carried an extra pair of sox pinned inside my shirt, and would try every night to change my socks, putting on the dry ones with foot powder (when I had it) and pinning the damp socks inside my shirt to dry them. In addition I would massage my feet. It seemed to work, and I never developed trench foot. On December 15, we were dug-in in a position outside of Bitche. An order came down shortly after noon for us to make an attack on a German position. Somehow, I was filled with apprehension about this attack. I remember that I knelt in our foxhole, and prayed that somehow the order could be changed. In a little while, we heard that the order had been rescinded and that the attack had been called off. Soon, however, the Germans began to shell us with mortar fire. Joe Collie and I were sharing a hole that day, and when the mortar barrage began, we both jumped into the hole. I happened to land underneath Joe. I felt a sharp pain in my left leg, and as soon as the shelling stopped, I asked Joe if he was hurt. “No” was his reply. I then said to him: “In that case, get off me, because I think I am.” Sure enough, I had a piece of shrapnel in the calf of my left leg. It had fortunately missed the bone and the knee joint, but it was serious enough that I needed to go to a hospital. So for me, the war took a different turn. I was brought to the Battalion Aid station by the company Jeep, and went from there to the 11th Evacuation Hospital in Bar Le Due by ambulance. The doctors set about immediately to remove the shrapnel which had entered the forepart of my leg, but which I could feel in the back of the calf when I rubbed my hand over it. They gave me an anesthetic (sodium pentothal) and told me to count to 50. I reached 9 or 10, and then didn’t remember anything until I awoke the next morning. It was not a painful wound as long as I was careful, and I thought that I would soon be walking again and going back to my unit. It happened that the Battle of The Bulge began that same day, and the medics were ordered to clear the hospitals to make room for the large number of casualties coming in from the front. I was labeled “Com. Z” (Communication Zone) and informed that I would be transferred to a hospital in England for recuperation. Thus, I escaped the worst part of the winter and some of the heaviest fighting our Division encountered.”

Operation Undertone, also known as the Saar-Palatinate Offensive, was a large assault by the U.S. Seventh, Third, and French First Armies of the Sixth and Twelfth Army Groups as part of the Allied invasion of Germany in March 1945 during World War II. A force of three corps was to attack abreast from Saarbrücken, Germany, along a 75-kilometre (47 mi) sector to a point southeast of Hagenau, France. A narrow strip along the Rhine leading to the extreme northeastern corner of Alsace at Lauterbourg was to be cleared by a division of the French First Army under operational control of the Seventh Army. The Seventh Army's main effort was to be made in the center up the Kaiserslautern corridor. In approving the plan, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower asserted that the objective was not only to clear the Saar-Palatinate but to establish bridgeheads with forces of the Sixth Army Group over the Rhine between Mainz and Mannheim. The U.S. Third Army of the Twelfth Army Group was to be limited to diversionary attacks across the Moselle to protect the Sixth Army Group's left flank. Opposing commanders were U.S. General Jacob L. Devers, commanding U.S. Sixth Army Group and German SS General Paul Hausser, commanding German Army Group G. Significantly assisted by operations of the Third Army that overran German lines of communication, Operation Undertone cleared Wehrmacht defenses and pushed to the Rhine in the area of Karlsruhe within 10 days. General Devers′ victory—along with a rapid advance by the U.S. Third Army—completed the advance of Allied armies to the west bank of the Rhine along its entire length within Germany.

Historical Reference to the Allied Offensive at Bitche during WWII (1944-1945):

“As the U.S. XV Corps, consisting of the 44th Infantry, 45th Infantry, 100th Infantry and 12th Armored Divisions, approached the German border, in early December 1944, the Germans stubbornly delayed the advance by forming strong-points around key road junctions and at Maginot positions. The missed opportunity to end the war in 1944, after the fall of France, would be paid for in blood. At Bitche, attached to the 44th, were the 749th Tank Battalion and 776th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and U.S. Army Aircorp P-47 units for bombing and strafing support. The assignment to reduce, capture and destroy this major (gros ouvrage) Maginot position was no picnic. Simserhof was yet untouched, undefeated in 1940, and was defended by elements of the well armed and tough 11th Panzer and 25th Panzer-Grenadier Divisions. Simserhof, a key defensive position in the German Siegfried Line, held the high ground and had to be taken in order to continue the advance into the Saar River plain and the Reich itself. The fortress was world-class and proven. And the Germans, always magnificent defenders, were now desperately fighting for their country and families. On December 16, 1944 infantry and engineers from the 44th Infantry Division, with supporting armor from the 749th and 776th Regiments, clambered through the mine-fields, artillery and machine gun fire, to the thick walls of the most powerful fortress in the world. The mission: capture Simserhof, part of the Maginot gros ouvrage fortress, the Ensemble de Bitche.”

“Making the army's main effort in the center, Haislip's XV Corps faced what looked like a particularly troublesome obstacle in the town of Bitche.”

“Bitche had been taken from the Germans in December after a hard struggle, only to be relinquished in the withdrawal forced by the German counteroffensive. On the army's right wing, Brooks's VI Corps—farthest of all from the Siegfried Line—first had to get across the Moder River, and one of Brooks's divisions faced the added difficulty of attacking astride the rugged Lower Vosges Mountains.”

“On the right wing of the XV Corps, men of the 100th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Withers A. Burress) drove quickly to the outskirts of the fortress town of Bitche. Perhaps aided by the fact that they had done the same job before in December, they gained dominating positions on the fortified hills around the town, leaving no doubt that they would clear the entire objective in short order the next day, 16 March.”

Siegfried Line:

The Siegfried Line combat assault by Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third Army in late 1944 on the Saar River and Merzig was a critical battle in the closing stages of World War II. The battle marked a significant turning point in the war, as it represented the first successful breach of the heavily fortified Siegfried Line, which had long served as Germany’s primary line of defence against an Allied invasion.

The Siegfried Line was a massive system of fortifications that stretched for hundreds of miles along the western border of Germany. The line consisted of concrete bunkers, anti-tank obstacles, and barbed wire entanglements, and was designed to slow down an invading army and provide time for the German army to mobilize and respond to an attack.

In late 1944, as the Allies continued their advance into Germany, Patton’s Third Army was tasked with breaching the Siegfried Line and pushing the German army back across the Saar River. The assault was a formidable challenge, as the Third Army was faced with a well-entrenched and determined enemy, as well as difficult terrain and harsh weather conditions.

Despite these challenges, Patton’s Third Army was able to achieve a decisive victory over the German forces in the Saar River and Merzig areas. The battle was fought with incredible ferocity and determination, with both sides showing remarkable bravery and resilience in the face of heavy casualties.

One of the key factors in the Third Army’s success was Patton’s aggressive and unorthodox tactics. Unlike many other military leaders of the time, Patton was known for his willingness to take risks and to think outside the box. He believed in the importance of speed and surprise, and he put these principles into action in the Siegfried Line assault.

One of the most notable examples of Patton’s unconventional tactics was his use of armored vehicles in the assault. He realized that the heavily fortified bunkers of the Siegfried Line would be nearly impervious to direct attacks by infantry, and he therefore ordered his tanks and armored vehicles to take the lead in the assault. This strategy allowed the Third Army to quickly break through the enemy’s defenses and establish a foothold on the other side of the Saar River.

Another critical factor in the Third Army’s success was the relentless determination of its soldiers. Despite the difficult conditions and heavy casualties, the soldiers of the Third Army fought on with incredible bravery and determination. They were motivated by a deep sense of duty and a desire to bring an end to the war and restore peace to Europe.

In the end, the Siegfried Line combat assault was a decisive victory for the Allies, and it marked a critical turning point in the war. The success of the Third Army in breaching the heavily fortified Siegfried Line paved the way for the final push into Germany and the eventual defeat of Germany.

The Siegfried Line combat assault was a testament to the bravery and determination of the soldiers who fought in the battle, as well as the strategic brilliance of their leader, General George Patton. It remains an important event in the history of World War II, and it serves as a reminder of the sacrifices made by those who fought and died to secure freedom and peace for future generations.