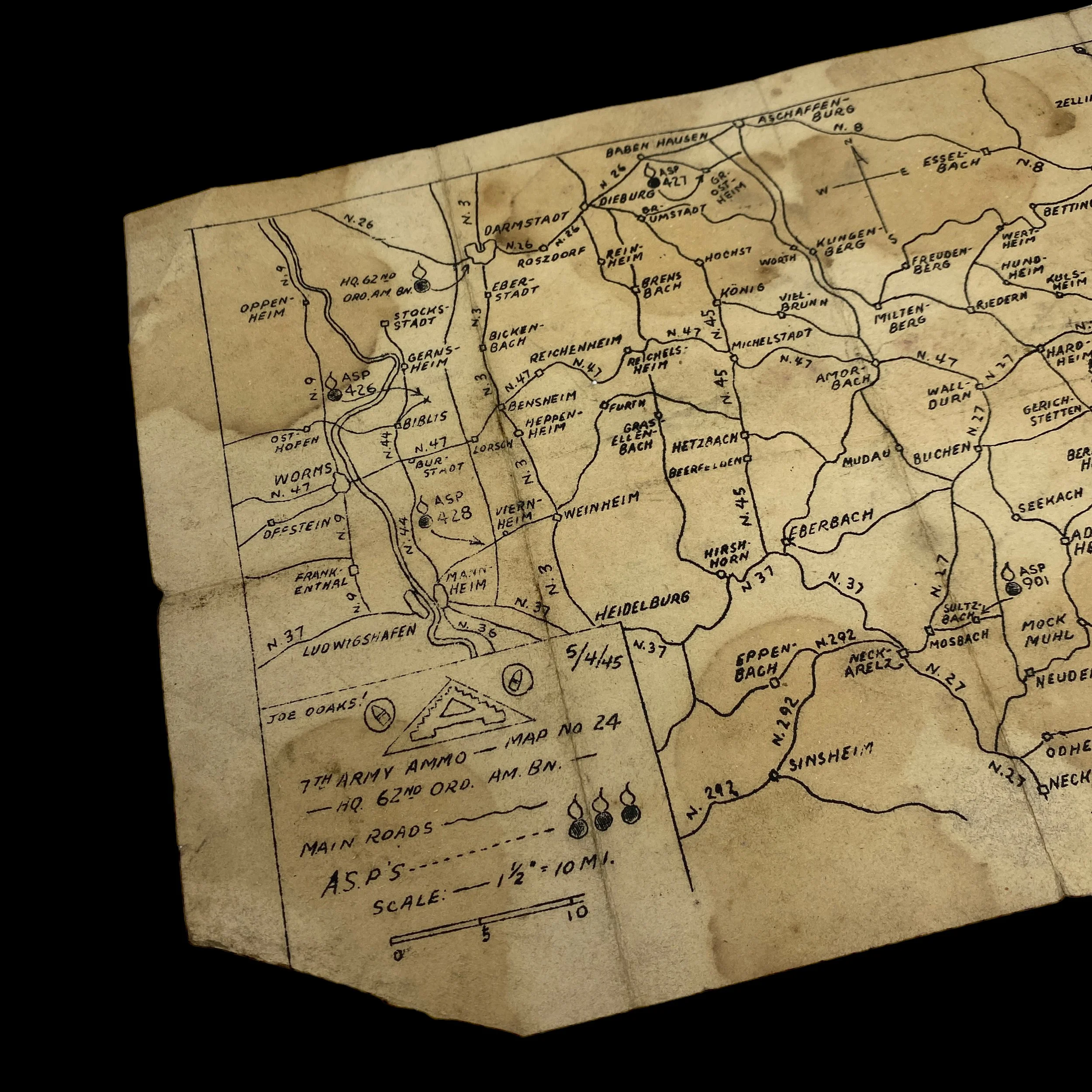

VERY RARE! Operation Plunder U.S. 7th Army General Patton's "Oppenheim & Worms" Rhine River Crossing Ammunition Supply Map

VERY RARE! Operation Plunder U.S. 7th Army General Patton's "Oppenheim & Worms" Rhine River Crossing Ammunition Supply Map

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

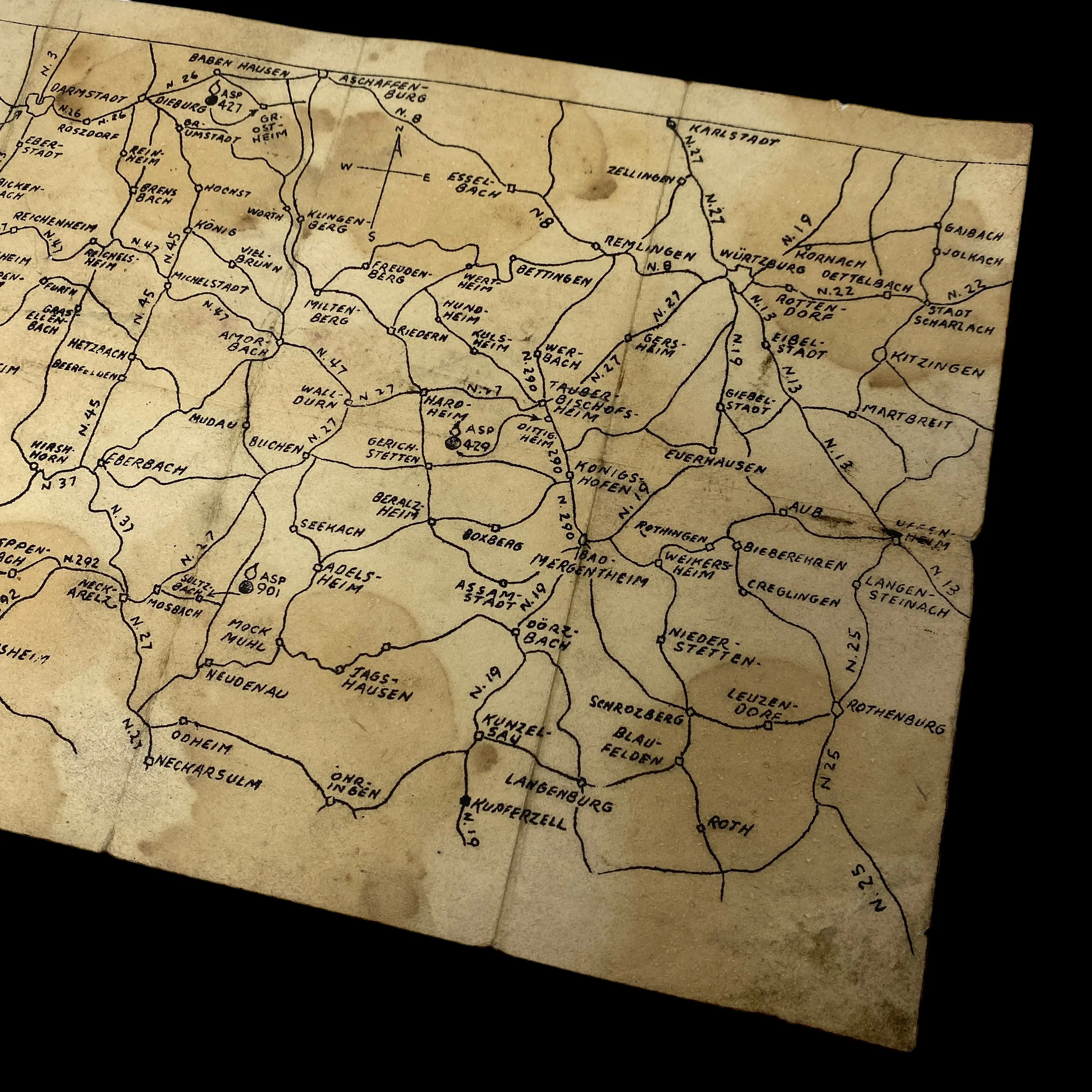

*This RARE map was used by the U.S. 7th Army and Patton’s first crossing of the Rhine River at Oppenheim and Worms.

Two invasions of France in mid-1944, Operation Overlord in Normandy and Operation Dragoon in southern France, succeeded in moving multiple American and Allied armies to the border of Germany. Attack momentum was delayed in late 1944 by serious logistical issues and by the setback in the Netherlands and fierce German resistance in the Huertgen and Ardennes Forests. But by January 1945, the Western Allies had overwhelmingly superior ground and air forces looming all along the western borders of Germany. The problem was, how to get them over the Rhine so that they could crush the last German resistance in the ETO and end the war.

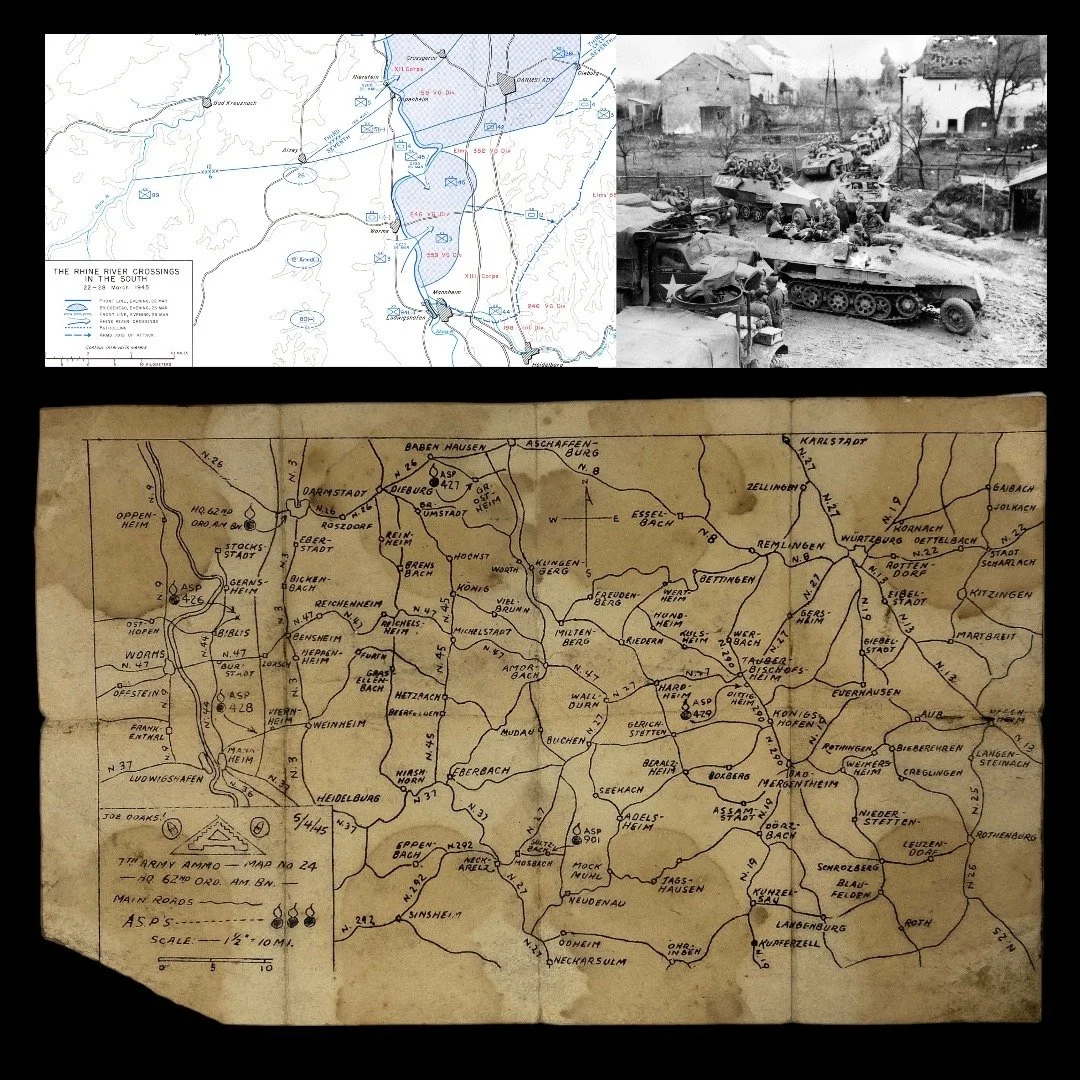

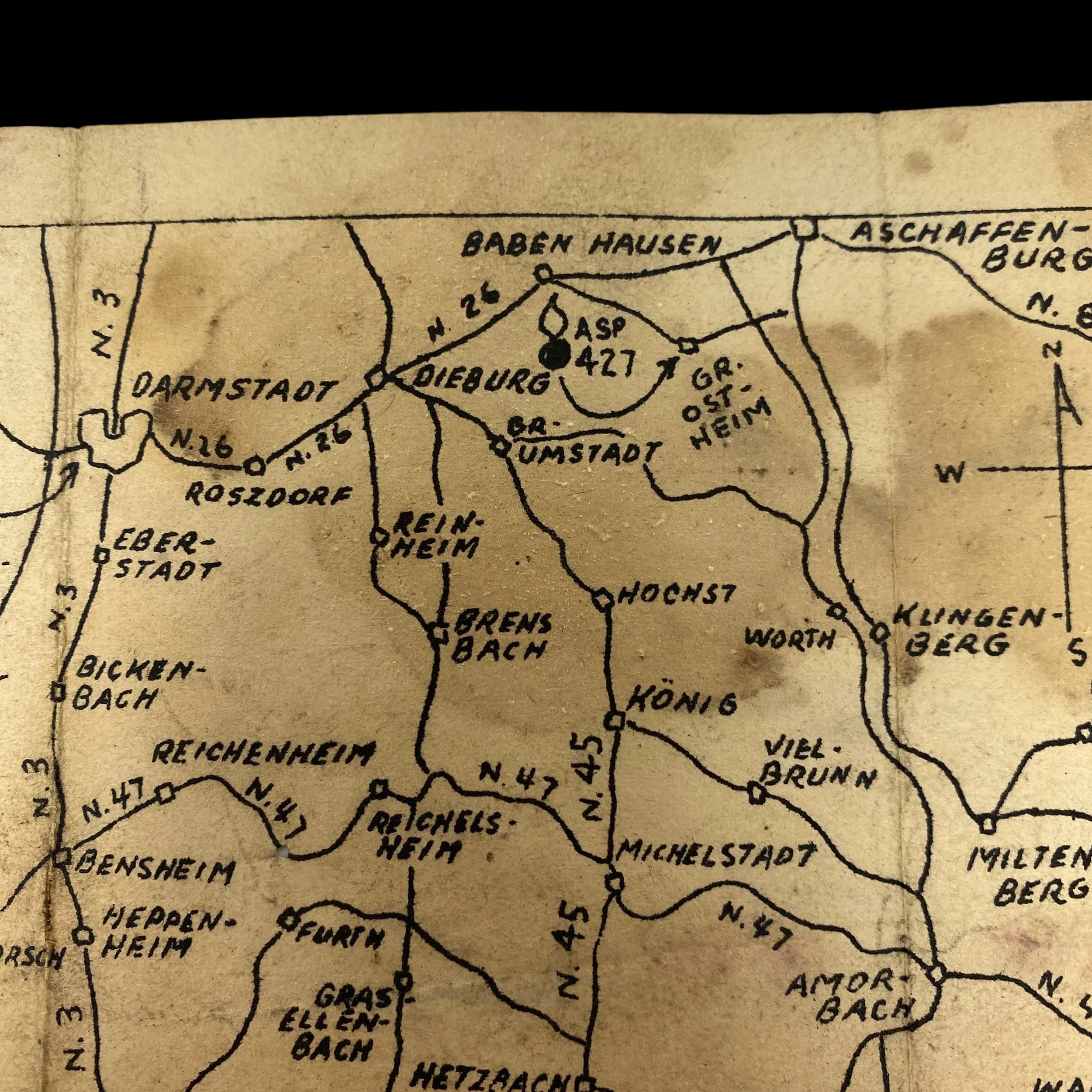

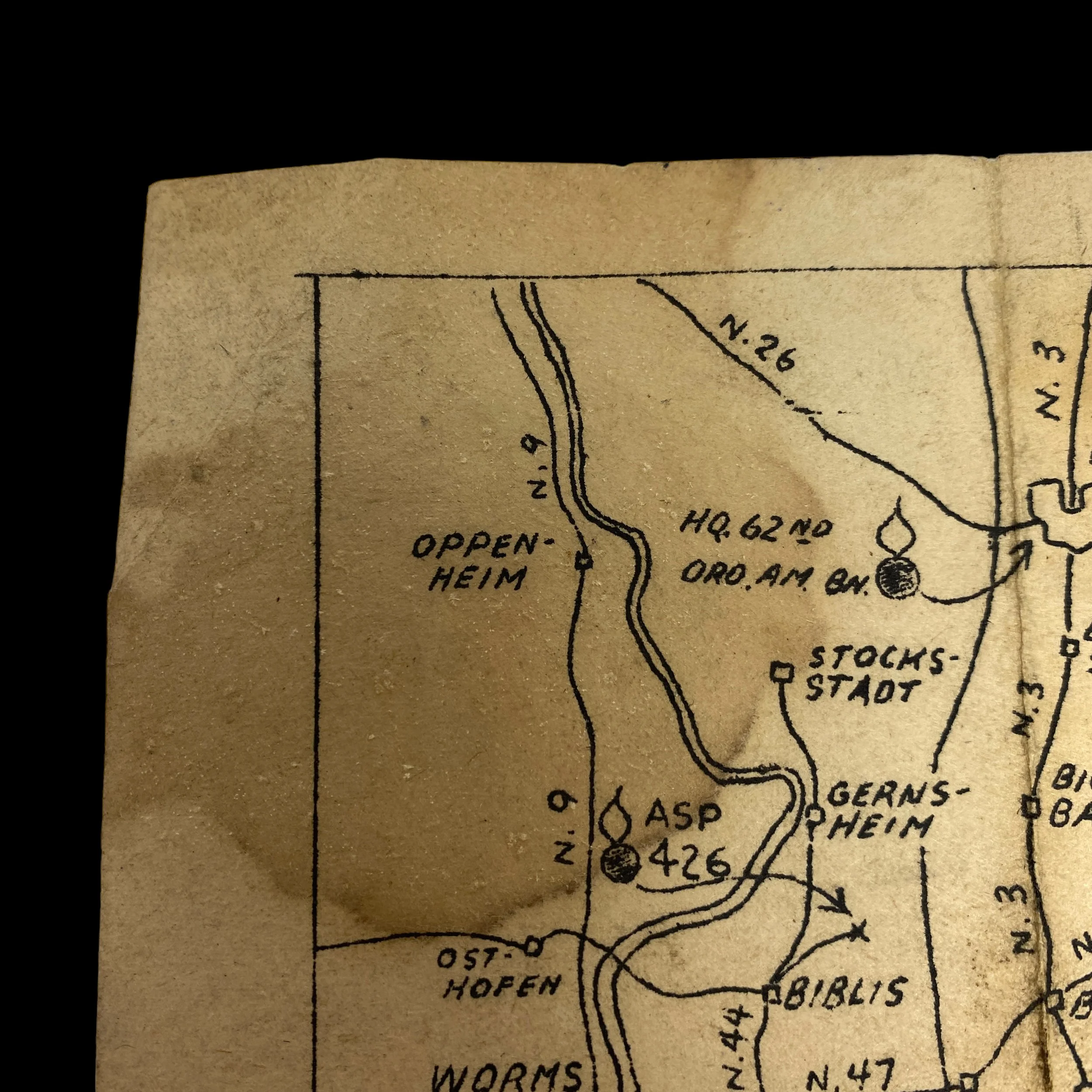

This incredibly rare and museum-grade Rhine River crossing combat assault map is an extremely limited hand-drawn 7th Army Rhineland Campaign map used by the 7th Army after crossing the Rhine River during Operation Plunder. This map shows heavy combat use and was used by the U.S. 7th Army to locate and navigate their own ammunition stations. This high-intelligence combat map would have been very SECRET and devastating if captured and in German hands as it located and pinpointed every 7th Army supply dump in the area. This was used on the battlefield as U.S. 7th Army infantry and armored divisions pushed retreating German forces further from the Rhine River. The techniques employed in the crossings of Third and Seventh Armies varied. General Patton got six battalions across with a fair degree of surprise by restricting artillery and air bombardment in his assault zones around Oppenheim and the Rhine gorge. Seventh Army, on Patton’s right flank, made comparatively heavier use of artillery in its assault near Worms. Common to all these efforts, however, was extensive engineer preparation beforehand.

The XII Corps Crossing at Oppenheim:

For months the engineers of XII Corps, scheduled to make Patton’s first crossing, had considered Oppenheim a good site. Because the Third Army operation was to be a surprise, a crossing at a town was essential to conceal the movement of the assault boats to the river’s edge. The engineers favored Oppenheim because it straddled one of the main roads to Frankfurt am Main, some twenty miles to the northeast. The bridge carrying the road over the river could not be counted on, but at that spot the Rhine was not more than a thousand feet wide and fairly slow, while its sandy banks were firm enough to support amphibious vehicles. For building rafts and launching LCVPs the protected Oppenheim boat basin on the near bank was ideal.

As planning progressed it became evident that some 560 assault boats would be available. This made it necessary to expand the plans to include a neighboring town, Nierstein, 1,500 yards downstream. During the assault at 2200 on 22 March, engineers of the 1135th Engineer Combat Group’s 204th Engineer Combat Battalion were to cross two battalions of the 5th Division’s 11th Infantry in column at Nierstein and the third battalion at Oppenheim. As soon as the 11th Infantry had cleared the far bank, the group’s 7th Engineer Combat Battalion was to put across the 5th Division’s 10th Infantry at Oppenheim.

On the morning of 22 March German planes bombed and strafed Nierstein, but nothing indicated that the enemy expected an immediate crossing there. The only activity the Americans could see on the far bank was a party of soldiers digging mine holes in the dike about fifty yards from the river’s edge. After dark on the twenty-second the 204th Engineer Combat Battalion brought assault boats down to the river’s edge. No artillery barrage was fired, nor did the boats use their motors. Three engineers manned each boat, which carried twelve infantrymen. As silently as possible, the boats paddled across in the blackness. The first boat from Nierstein drew a single burst of machine-gun fire, but the infantry replied with automatic rifles and before the boat unloaded five Germans came down from the dike and surrendered. The first infantry company was ashore in eight minutes, and by 0130 on 23 March all three battalions of the 11th Infantry were over the Rhine with only twenty casualties. Strongest resistance had occurred in the Oppenheim crossing,during which one engineer was killed.

At 0200 the 7th Engineer Combat Battalion began crossing the 10th Infantry in a column of battalions. Just at daylight, as the last wave was paddling across, shells from a German self-propelled 105-mm. gun hit the water, splashing and swamping some of the boats but causing no casualties. The gun could not be driven off or silenced until the ferries went into operation to carry across heavy weapons. Meanwhile, enemy shelling, bombing, and strafing interfered with the work at the Oppenheim boat basin where the 88th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion was constructing four Class 40 rafts. The first raft, pushed downstream to Ferry Site 1 near Nierstein, did not begin operating until 0700, when it carried a bulldozer to the far shore; it was 0830 before lank destroyers could raft across to attack the self-propelled gun. During the night a party of engineers had marked beaches for the landing of DUKWs, LCVPs, and Weasels using blinking white, red, and green lights and setting up vertical panels of corresponding colors for daytime use. Some LCVPs were working by dawn on 23 March, but DUKWs and Weasels did not arrive until the next day.

The 2nd Infantry of the 5th Division crossed to the east bank on rafts and LCVPs next morning, and by midafternoon an attached battalion of the 90th Infantry Division had also crossed. Two of the big rafts could accommodate six jeeps at a time; they operated continuously for two days and nights, one pushed by an LCVP, the other by two powerboats. The rafts continued supply and evacuation operations even after bridges were in, a treadway at 1800 on 23 March and a heavy ponton bridge at 0700 the next morning. The raft operations permitted the 4th Armored Division to employ the treadway as a one-way crossing, and the division used the bridge continuously for twenty-four hours beginning at 0900 on the twenty-fourth.

In one respect the engineers of the 1135th Engineer Combat Group showed more foresight than had their colleagues in the First and Ninth Army crossings. When the construction of the heavy ponton bridge began, all ferries moved to Ferry Site 2, downstream of all bridges. There, the U.S. Navy was operating LCVPs, and DUKWs began operations on the twenty-fourth. This movement downstream assured that the ferries would not crash into the bridges.

The 150th Engineer Combat Battalion began bridge work at 0330, but German artillery fire at dawn and strafing and bombing during the morning interrupted the work. American combat troops on the east bank soon silenced the artillery piece, and although the bombing and strafing wounded one man, the air attacks did little damage to the bridge material.

About the time bridge building began, a detachment of the 1301st Engineer General Service Regiment, experienced in boom construction, started emplacing an antimine floating log boom and an antipersonnel boom made of admiralty netting, both upstream of the bridges. The engineer detachment completed the log boom by 1400 on 23 March. The more troublesome antipersonnel boom was only half completed by nightfall, but during the night two German frogmen were caught in its meshes. Each carried two disc-shaped magnetic mines, both set to explode at 0600. The Germans said they were two of a party of five frogmen who dropped into the river about eleven kilometers upstream with orders to place mines on either a ferry site or a bridge. They had almost immediately lost contact with the other three, who were never picked up. The two captives were soldiers who had been sentenced to three months’ service in a naval diving school for offenses committed in Russia and in Greece. On this penal service, they revealed, they could not handle explosives and received their mines only when they were actually in the water upstream of Rheinberg. The officers had also told them that they had little chance of returning from the mission.

The Seventh Army Crossings:

About fifteen miles south of Oppenheim lay Worms, where the Seventh Army was to cross the Rhine. The fact that operations there and at the Oppenheim bridgehead would be mutually supporting outweighed the disadvantages of the terrain at Worms. On the far bank, some eight miles east of the Rhine, the hills of the Odenwald rose sharply. On those heights the Germans could make a stand and contain the bridgehead—if they had men and weapons to do so. Enemy strength was difficult to estimate, but Seventh Army intelligence indicated that the Germans had not more than fifty men per river-front kilometer and no large guns permanently emplaced east of the Rhine.26

Early Seventh Army plans and preparations, begun in September 1944, had envisioned a Rhine crossing about twenty miles upstream from Worms and south of Mannheim. For that reason a good deal of the engineer planning concerned the possibility that the Germans might open power dams upstream from Basel to create flood waves that could wash out tactical bridges as far north as Mannheim, leaving American assault troops stranded on the far shore. To provide warning of approaching floods so that floating bridges could be safeguarded, the ETOUSA chief engineer established a flood protection service in his office; engineers at the headquarters of the various armies set up similar organizations. To collect planning data, 6th Army Group engineers experimented with hydraulic models of the dams between Basel and Lake Constance.27 This effort decreased in importance when 6th Army Group learned that the Swiss were prepared to protect the dams along their border with Germany. Moreover, Seventh Army changed its crossing site to Worms, north of Mannheim.

The 40th and 540th Engineer Combat Groups, both amphibious veterans, were available to put Seventh Army’s XV Corps across the Rhine on a nine-mile front extending north and south from Worms. Training had begun in September 1944, when Seventh Army’s rapid advance inland through southern France made a November or December Rhine crossing appear likely. During those months the Rhine current is swift, usually from eight to ten miles per hour. Accordingly, the Seventh Army engineer, Brig. Gen. Garrison H. Davidson, felt that hand-paddled assault boats would be out of the question. He would need the services of boat operators who had trained at sites on the Rhine and Doubs rivers to pilot motor-driven boats. To prepare for a swift-current crossing the engineers also experimented with stringing cable to help DUKWs take artillery across promptly and with anchoring ponton bridges.28

In the event, much of the time spent preparing for a swift-current crossing was wasted. By the 26 March crossing date, the current was only three or four miles per hour, slow enough to use paddle-powered assault boats. In the sector north of Worms, where XV Corps’ 45th Infantry Division supported by the 40th Engineer Combat Group crossed the river, using powered boats actually proved detrimental because motor noise alerted the enemy. In addition, the engineers found that DUKWs and duplex-drive tanks could cross without the aid of cables.29

Around midnight on 25 March a four-man patrol of the 180th Infantry, 45th Division, paddled across the Rhine in a rubber boat to reconnoiter the east bank. The patrol saw some German soldiers but was not fired upon and, after searching fruitlessly for gun emplacements and mines, returned safely to the near bank in time to take part in the assault crossing at 0230.30 The heavy storm and assault boats, brought to the riverbank on carts borrowed from the Chemical Warfare Service, were launched on schedule from stone-paved revetments. Mist rising from the river hid the moon. To achieve surprise the attackers used neither smoke nor any preliminary artillery barrage. However, after the Germans heard the roar of the motors, small-arms, 20-mm. antiaircraft, and mortar fire hit the boats as they reached the far bank. This fire was heaviest in the 180th Infantry’s sector, where 60 percent of the boats were damaged; the 179th Infantry lost only 10 percent of its boats. All fourteen of the duplex-drive tanks in the assault went across safely. With the help of the tanks and of artillery ferried over in DUKWs or on infantry support rafts, the infantry overran the Germans and made good progress on the ground. During the crossing the 2831st Engineer Combat Battalion, piloting the storm and assault boats, suffered eighteen casualties; the 2830th Battalion, which operated rafts and ferries, sustained none.31

Just south of Worms, the 3rd Division made two feints across the Rhine below Mannheim on the evening of 25 March which alerted the enemy. When the 540th Engineer Combat Group’s 2832nd and 2833rd Engineer Combat Battalions began moving toward their assembly areas at 2000 hours—the former to support the 7th Infantry on the south, the latter the 30th Infantry—they came under German artillery and mortar fire. This fire continued while the engineers pulled the storm and assault boats over the steep, revetted banks and into place for the crossing. In the 7th Infantry zone flames from a barn set on fire by a German incendiary shell lit up the crossing area, silhouetting the men and boats.32

At 0152 friendly artillery began a massive barrage that continued until H-hour, 0230. Four minutes before the barrage lifted, 7th Infantry boats began moving across the river, and by 0340 both assault infantry battalions were over. In the 30th Infantry’s zone, where opposition was lighter, the two assault battalions were across by 0330. The artillery barrage, as well as the use of smoke, kept the loss rate of storm boats to only 10 percent. Ten of fourteen duplex-drive tanks reached the far shore. About H plus 2 the first DUKW crossed the river safely without cables. The engineers also found that cables were not necessary for the rafts, which by 0700 were ferrying tanks and vehicles across the Rhine. Nevertheless, since the ferrying operations lay upstream from where floating bridges were being built, the engineers strung cables and used them to keep ferries from being swept downstream to crash into the bridges.

The engineers who were to build a mine barrier and patrol the river to protect the bridges from floating mines, frogmen, and other menaces reached their assembly area, farthest upstream of all, at 0300. The fire from German antiaircraft guns, ranging in caliber from 8-mm. to 128-mm. and emplaced on an island in the Rhine, drove the engineers off. Heavy fire from the island, a fortress that had apparently escaped the notice of Seventh Army planners, continued throughout much of D-day, harassing the 7th Infantry’s crossing site and holding up the barrier work. It was late afternoon when a battalion of the 15th Infantry assaulted the island from the east bank of the Rhine and silenced the guns. On D plus 1 the engineers erected the mine barrier, and the river patrol went into operation with searchlights, artillery, and DUKWs mounting quad-50 machine guns. The patrol sank a number of barges that might have destroyed the downstream bridges.

Fire from the German guns on the island also delayed construction of the nearest floating bridge, a treadway south of Worms. The 163rd Engineer Combat Battalion began work at 0600 on D-day but did not complete the treadway until 1850. The first usable bridge was a heavy ponton span at Worms, about two hundred feet downstream from the site of the Ernst Ludwig highway bridge, which the Germans had demolished. In just over nine hours the 85th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion built the l,047-foot ponton; open to traffic at 1512 on D-day, it was named the Alexander Patch Bridge for the Seventh Army commander. Although the handsome stone tower of the Ernst Ludwig Bridge, still standing on the far bank, harbored enemy snipers, ruins of the span provided good anchorage for the bridge builders. The Alexander Patch Bridge carried 3,040 vehicles eastward during its first twenty-four hours of operation.33 Because of its early completion and excellent location, Seventh Army preferred the Alexander Patch Bridge to a ponton bridge the 1553rd Engineer Heavy Penton Battalion erected downstream near Rheinduerkheim in the 45th Division’s sector. As a result, that bridge operated at only half its capacity.34

On 29 March, General Davidson, the Seventh Army engineer, instructed the 85th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion to build a bridge to take tanks and vehicles over the Rhine to Mannheim. With the help of aerial photographs a reconnaissance party found a suitable site at Ludwigshafen, on the west bank opposite Mannheim. Eight bulldozers worked six hours clearing rubble from the streets and preparing the site, and the 1553rd Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion brought pontons down from the Worms area on its trailers. Construction started at daylight on 30 March. The bridge opened to light traffic at 1500, but tanks and heavy vehicles had to wait until 1900 because of a delay in obtaining two-inch decking. The engineers dubbed the span the Gar Davidson Bridge to honor the Seventh Army engineer.