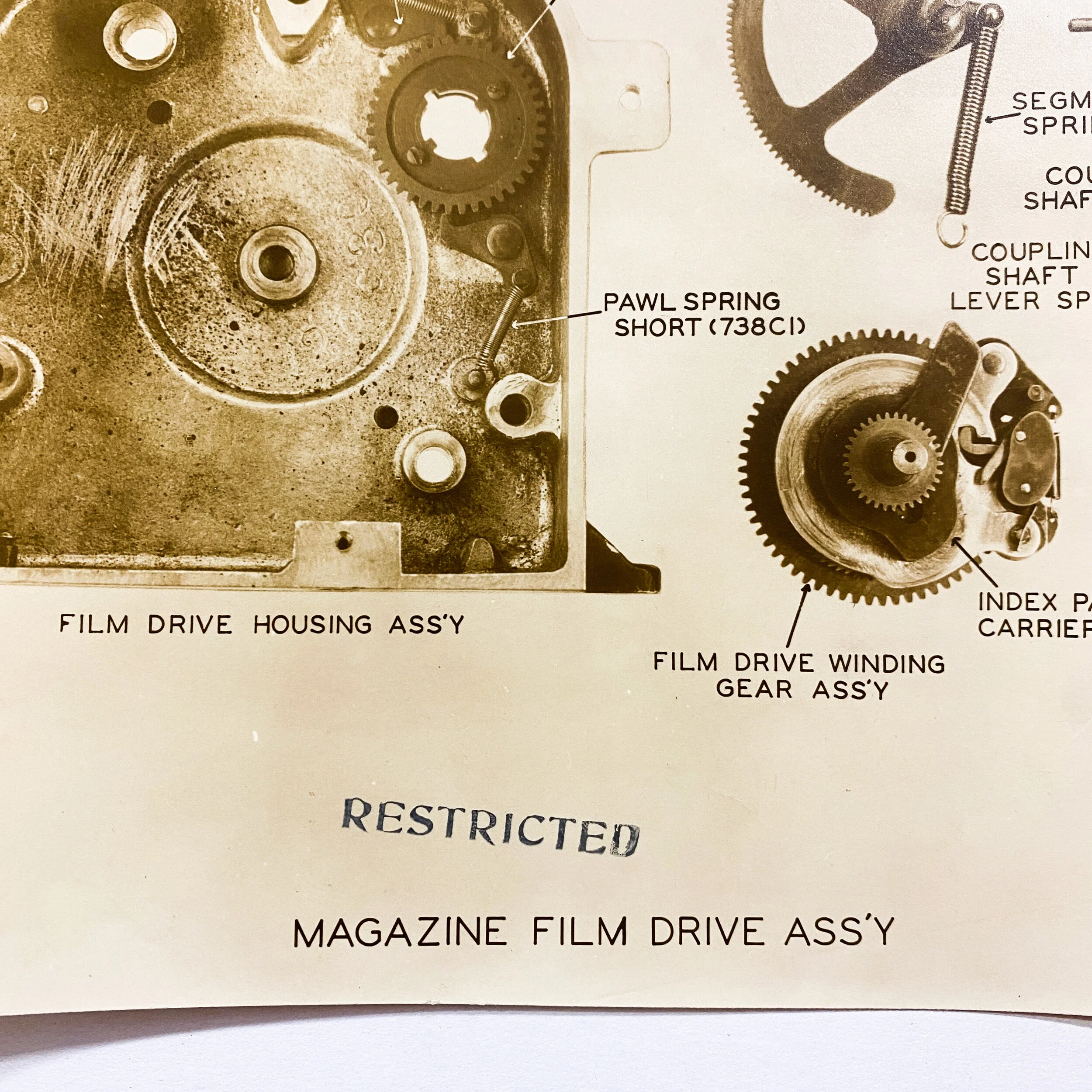

'RESTRICTED' Magazine Film Drive Ass’y Diagram - Sgt. Joseph F. Wroblewski - 33rd Photo Reconnaissance Squadron

'RESTRICTED' Magazine Film Drive Ass’y Diagram - Sgt. Joseph F. Wroblewski - 33rd Photo Reconnaissance Squadron

Size: 7.5 x 9 inches

Compared with fighter jocks and bomber crews…the pilots, camera operators, and photo developers of the photo reconnaissance squadrons were among the unsung heroes of World War II. They not only conducted various ‘Top Secret’ missions, but flew many of their missions with unwavering courage under enemy radars and with nothing but aerial cameras on board their aircraft. The Ninth Air Force’s 33rd and 34th Photo Reconnaissance Group, served as the “eyes of the Army” in Europe, flying some of the war’s most dangerous missions. In the spring of 1944 Sgt. Joseph F. Wroblewski was one of many men of the 33d Photo Reconnaissance Squadron tasked with a particularly important mission: photographing the beaches of Normandy prior to the D-Day invasion. The group’s mount of choice was the Lockheed F-5, a stripped-down version of the P-38 equipped with cameras instead of guns. Sgt. Joseph F. Wroblewski, a camera repair and maintenance operator, outfitted and serviced these unique Lockheed F-5 that would fly at wave-top level above the English Channel in order to slip under German radar. The F-5 pilots photographed Normandy’s beaches at an altitude between 15 and 50 feet and an average speed of 350 knots. These low-altitude sorties, which the pilots likened to the roll of dice at a gambling table, were called “dicing” missions. One never knew how they would turn out.

This WWII ‘RESTRICTED’ stamped aerial reconnaissance digram is titled, “Magazine Film Drive Ass’y”. The film drive was used in various Allied reconnaissance cameras to digitally photograph enemy gun emplacements, buildings, movement, etc. To specifically improve the overall operating performance of the continuous strip camera and strip photography in general, an improved model is presently under development. It will have a non-banding precision film drive mechanism, a stabilized mount, larger film capacity and several other features. While the first continuous strip cameras were designed for extremely low altitude high speed photo reconnaissance, a new type of stereoscopic strip camera now being developed is intended to meet the requirement for high altitude strip photography.

Collection of Sgt. Joseph F. Wroblewski:

This exclusive collection of ‘RESTRICTED’ World War II camera reconnaissance blueprint diagrams, “CONFIDENTIAL” aerial photographs, and other personal training papers are from the collection of Sgt. Joseph F. Wroblewski of the 33d Photo Reconnaissance Squadron - U.S. Army's 9th Air Force. These materials are dated as early as 1943 when Sgt. Wroblewski and his squadron were training for what would be one of the most dangerous, secret, and important early missions of WWII. Throughout WWII Pvt. Wroblewski (1943) worked his way up the ranks to Sgt. Wroblewski as an aerial camera repair operator for the 33rd P.R.S. The maintenance of these cameras was crucial for the squadrons successes. The highly classified aerial photos taken by the cameras prepared by Sgt. Wroblewski paved the way for Allied victory in France and gave the Allies a strategic insight for the opening Allied amphibious assault of the Normandy beaches his cameras photographed months and weeks prior.

The book “Eyes of the Enemy” by Roy Teifeld and Bernice C. Teifeld featured below references quotes from the actually veterans of the 33rd and 34th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron:

Our commanding officer, Colonel W. Donn Hayes, wrote in his journal: “A total of eleven low-level ‘dicing’ missions were flown by the 10th PR Group over occupied Europe’s beaches from May 6 through May 20, 1944. The detail of photos taken on these missions was such that, in the two weeks prior to the invasion, a scale model of Omaha Beach was built, complete with natural features of the beach trees, houses and other buildings, obstacles built by the Germans, as well as other enemy installations known to exist at the time. Along with low and high altitude photography, the area was studied and memorized by the Combat Engineers charged with the task of clearing the obstacles for the landing craft and invasion forces that would follow.”

In order to minimize the chances of discovery, the F-5s flew these missions alone and unescorted. The pilots learned how dangerous it was to undertake a mission with more than one plane when they attempted a sortie with 12 F-5s. The Germans quickly recognized the P-38’s distinctive silhouette and opened up with a furious barrage of anti-aircraft artillery.

Colonel Hayes described the first dicing mission, flown by 1st Lt. Albert Lanker of the 31st PRS on the morning of May 6: “Lanker flew from Chalgrove [a U.S. Army Air Forces base near Oxford, England] to the other side of the Channel at the village of Berques-sur-Mer. Low tide made it possible for him to fly fifteen feet above the waves. Reaching the beach, he turned around a large sand dune to lessen his chances of being hit while turning. His photos later showed this dune to be an enemy gun position. Other photos in the run showed gun emplacements in the cliffs, details of beach obstacles and weak spots within the defenses.

“Racing just above the beaches, cameras on runaway, he encountered five groups of men at work on beach defenses. In each case he headed straight for the group just to watch them scatter and roll. He said they were completely surprised and didn’t see him until he was almost on top of them. He was fired upon repeatedly at point blank range by riflemen but was not hit. They didn’t realize his plane had no guns and didn’t even dream he was using a camera to photograph the terrain. Then he scaled the cliff at the end of his photo run, cleared the top by about six feet and returned safely to Chalgrove.”

During the second dicing mission, Lieutenant Allen R. Keith of the 34th PRS collided with a seagull, which shattered the glass of his windscreen and struck the bulletproof glass that had been installed behind it at the lastminute suggestion of assistant crew chief Lee Weigand. “The glass was covered with blood, swirling feathers and bird parts,” Hayes related. “It only took a couple of seconds to wipe the blood off his goggles, during which time Lieutenant Keith maintained control of his plane and returned with photos showing wood and concrete posts topped with teller mines connected with trip wires. They also showed gun positions located in the sides of cliffs and weak spots within the defenses.”

When Lieutenant Garland A. York returned from his dicing mission it was found that he had photographed the exact section of the Normandy beaches upon which the American forces would land. “He had photographed all of Omaha and most of Utah beaches,” wrote Hayes. “His photos showed the cliffside gun positions, defensive weak spots and obstacles placed so that any landing craft would be stopped within the killing zone of defensive German machine gun emplacements and steel hedgehogs as infantry stoppers.”

https://www.historynet.com/eyes-of-the-army.htm