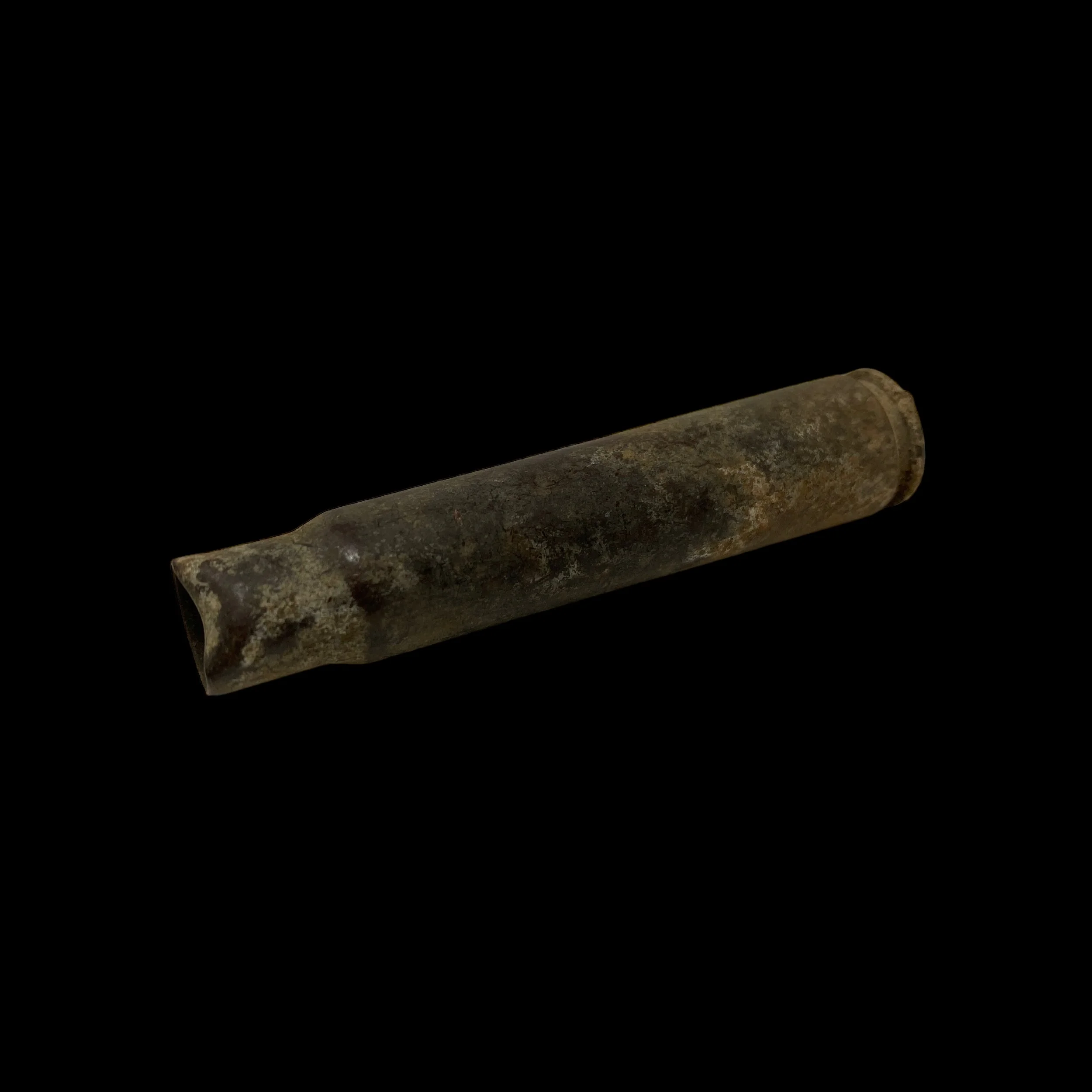

RARE! WWII July 1944 Battle of Saint-Lô' Normandy France Battlefield Recovered Fired Nazi German Bullet Casing

RARE! WWII July 1944 Battle of Saint-Lô' Normandy France Battlefield Recovered Fired Nazi German Bullet Casing

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A. and a full historical write-up

“Located only 20 miles from the D-Day Beaches of Omaha and Utah Beach, a number of major roads in Normandy intersect at Saint-Lô. Taking it would allow the Allies access to the entire region and provide an avenue of advance towards Paris. Germans knew the importance of the town and realized if they could hold onto it, the Allies would be trapped. The fight for Saint-Lô would be some of the bloodiest in the Normandy campaign.”

This incredible and museum-grade WWII artifact was recovered during a professional excavation and preservation of the Battle of Saint-Lô' France battlefield. This fired German bullet casing was a part of the intense fighting between German and American Divisions in the Normandy region following the D-Day landings on June 6th, 1944.

The assault of Saint-Lô' was known for its hedgerow, savage, and close-quarters fighting. The countryside approaching the town was divided by a deadly maze of earthen embankments known as hedgerows. Fighting through this bocage country was famously bloody as combatants engaged each other at distances sometimes of just a few yards. Ground had to be won step-by-bloody-step in close-fought infantry battles from one field to the next. Soldiers could often not see much farther than the next hedgerow and frequently scurried over one only to come face to face with the enemy. “On along the hedge and—there are men standing looking at me—they are not GIs! They are Germans!” recalled medic Gordon Cross after one particularly harrowing encounter with the enemy.

What makes this fired artifact extremely rare is the gravity and role it played in the fighting. Overall, the fight for Saint–Lô was one of the bloodiest chapters of the war in Europe. Between July 3 and 22, more than 11,000 U.S. GIs were killed there. German casualties are estimated to be similar. Ninety percent of the Americans killed in the battle in infantry units. In my grandfather’s company, only six of the original 42 men survived. “I started thinking of what I could have done to have saved them,” he’d remember later. “And I had such a sad and remorseful feeling come over me that I started crying like a baby. The company commander thought I might be losing it, but I told him that I just felt such sorrow.”

Full History of the Battle of Saint-Lô':

The Allied forces’ hard-won foothold on the bloody beaches of Normandy, France, on D-Day, June 6, 1944, was only the beginning of what would become a costly, foot-slogging effort to retake—field by field, town by town and house by house—all French ground the Germans had occupied since 1940. Myriad small farms and villages on the Allies’ line of march paid a bitter price for their liberation, with entire towns left in rubble and thousands of citizens killed. Among the hardest hit was the village of Saint-Lô.

Within 20 miles of the Normandy coast, the once-picturesque community of 11,000 had long been the provincial seat of the Manche government. It also had the wartime misfortune to straddle the junction of seven roads and a railroad line. The vital crossroads was a key to the success of the Allied invasion. As historian Ted Neill wrote, “Taking [Saint-Lô] would allow the Allies access to the entire region and provide an avenue of advance toward Paris.”

The Americans were well aware of this, as were the Germans. On D-Day the Allies had bombed the town’s power plant, railroad station and most other buildings in an effort to prevent enemy troops and tanks from passing through. American and British planes had dropped leaflets over the town the day before, warning citizens to evacuate. But strong winds had scattered the flyers, leaving residents unaware of what would befall them. The resulting mortality list approached 800, including dozens of French partisans the Germans were holding in Saint-Lô Prison, which was reduced to rubble. Before the campaign was over, Saint-Lô would be bombed twice more by the Allies and once by the Germans. Nearly the entire town was leveled, earning it the chilling epithet, the “Capital of Ruins.”

The hellish contest for the crossroads and the miles of tangled countryside leading to it was destined to become one of the bloodiest in the European Theater of Operations. In less than three weeks it cost thousands of GI lives, with tens of thousands more wounded or missing.

By the beginning of July 1944—three weeks after D-Day—Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy, was not progressing as rapidly as anticipated. The British Second Army had yet to secure one of its primary objectives, the pivotal crossroads city of Caen, effectively halting its advance on Paris before it began. To block the Second Army the Germans had deployed a staggering force of tanks and armored fighting vehicles along a tight 20-mile front.

Farther to the west the American First Army under Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley had just achieved its first tactical objective by seizing the port city of Cherbourg, on the northern tip of the Cotentin Peninsula. But with the exception of V Corps, which had begun its southward push on June 9, First Army had progressed no further in breaking out of the peninsula. Resupplied and reinforced, Bradley ultimately launched an early July offensive, consisting of 14 divisions in four corps along a 25-mile front, only to encounter obstacles that slowed his advance to a crawl.

The worst seasonal torrential rains in local memory turned the marshy ground to soup, rendering rapid forward movement difficult at best. This delay provided the German Seventh Army, by then significantly reinforced, with more time to establish formidable defenses. Worse yet, a captured American field order citing Saint-Lô as the primary Allied objective gave the Germans the opportunity to dig in along the likeliest routes of advance.

The most formidable obstruction to First Army’s rapid forward movement was the countryside itself. Spreading out from the base of the Cotentin was countryside dotted with small farms, many comprising less than an acre of orchard or plowed ground, each bordered by thick hedgerows. The barbed hedges ranged anywhere from 4 to 15 feet in height. Along each row ran a deep, high-banked trench. “From a military perspective,” historian Steven Zaloga wrote, “the hedgerows created a network of inverted trenches, forming a natural, fortification system that was well suited to defense.”

War correspondent Ira Wolfert gave a contemporaneous eyewitness account of the terrain in a July 12 dispatch:

“The hedges are thick and green and all brambly. You can’t see through them if you stick your face into them to look through. It’s like trying to look through a mask. Under every hedge is a German slit trench—one, three or five of them, dug right into the roots of the hedges. Men who know a great deal about war built them. A battalion today was driving due south on Saint-Lô, and there were Germans ahead of them and on two sides of them, waiting behind hedges in every field with mortars, machine guns, rifles and machine pistols.…Our artillery couldn’t drive them the conventional 6 feet under, unless it hit each one separately on the head.”

The landscape proved invaluable to the Germans in their efforts to establish an impenetrable defense. The centuries-old maze of small fields, steep earthen embankments and thorny hedges—known to locals as bocage—to an extent negated Allied air superiority. The difficulties lay in accurately spotting and targeting the enemy and in distinguishing friend from foe in a contest defined by continual close-quarters fighting.

For all its effectiveness, Allied artillery faced similar obstacles. The hedges and trees impeded effective artillery fire, often blocking and detonating outgoing rounds before they reached their targets. Even basic rifle fire had its limitations in such country, due to the effective cover the hedgerows offered defenders. To compensate, GIs increasingly turned to the use of rifle grenades, bazookas and 60 mm M2 light mortars.

Armored support was also limited. Beyond the difficulty of motoring through the thick terrain—even with improvised bulldozer, hedge-cutter and timber-prong modifications welded to their bows—tanks exposed their underbellies when rolling up over the steep embankments, providing easy targets for the Germans’ tank-busting Panzerschreck and Panzerfaust rocket launchers.