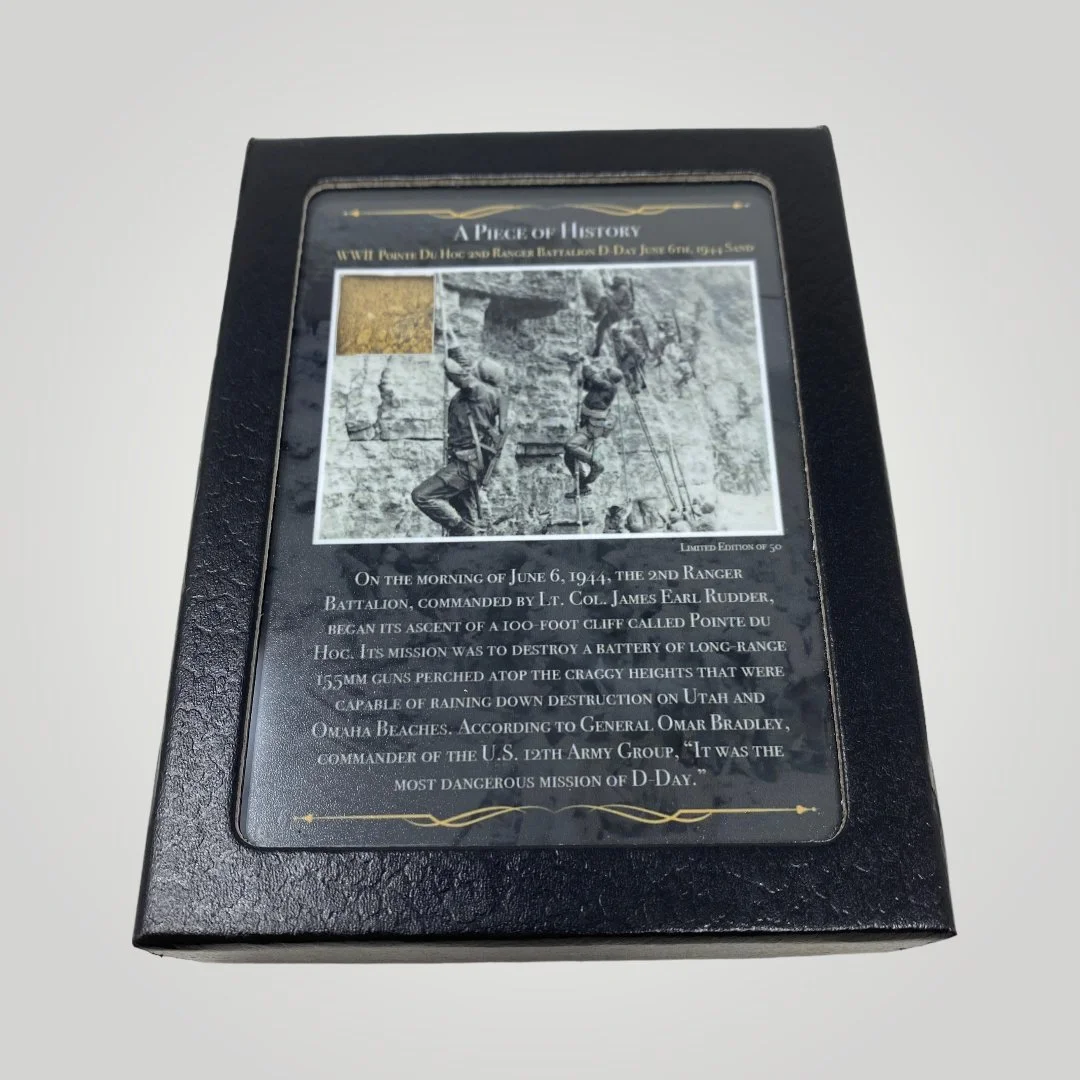

RARE! WWII D-Day Pointe du Hoc "Ranger Battalion Mission" June 6th, 1944 Sand with Display Case (C.O.A. Included)

RARE! WWII D-Day Pointe du Hoc "Ranger Battalion Mission" June 6th, 1944 Sand with Display Case (C.O.A. Included)

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A. and a full historical research write-up.

*Limited Edition of 50*

Own your piece of history today!

Due to an incredibly high demand for display case options we are proud to offer one of our LIMITED EDITION series of HISTORIC DISPLAY CASE EXCLUSIVES. This incredible “Piece of History“ is professionally encased in a glass display case with plush padding and a tightly sealed display case. Each displays features a historical photograph and short description that corresponds to the artifact displayed. This display case measures a perfect 4.25 inches tall x 3.25 inches wide.

This series is a limited edition of 50 pieces, meaning that each “Piece of History” display is unique. The artifact you receive may vary slightly from the display shown.

The events of June 6, 1944, commonly known as D-Day, stand as a pivotal moment in world history. The Allied forces executed a daring and audacious plan to liberate Nazi-occupied Europe. Among the various landing sites, Utah Beach played a crucial role in the success of the operation.

Located halfway between Omaha Beach and Utah Beach, the Pointe du Hoc dominates the sea from its vertical cliff. Pointe du Hoc was the location of a series of German bunkers and machine gun posts. Prior to the invasion of Normandy, the German army fortified the area with concrete casemates and gun pits. On D-Day, the United States Army Provisional Ranger Group attacked and captured Pointe du Hoc after scaling the cliffs. United States generals including Dwight D. Eisenhower had found that the place housed artillery that could slow down nearby beach attacks.

The U.S. 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions were given the task of assaulting the strong point early on D-Day. Elements of the 2nd Battalion went in to attack Pointe du Hoc but delays meant the remainder of the 2nd Battalion and the complete 5th Battalion landed at Omaha Beach as their secondary landing position.

Though the Germans had removed the main armament from Pointe du Hoc, the beachheads were shelled by field artillery from the nearby Maisy battery, on the fire support plan of heavy cruiser HMS Hawkins. The rediscovery of the battery at Maisy has shown that it was responsible for firing on the Allied beachheads until 9 June 1944.

This very rare and very historic piece of WWII history is very rare Pointe du Hoc sand that was preserved during a professional D-Day preservation and artifact recovery effort during the 50th D-Day anniversary in 1994.

In February 1944, it is crowned by a German coastal battery: six kilometers west of Omaha, six French-made 155 mm howitzers (155 mm GPF mle 1917) and dating from the First World War are set up on a plateau that ends abruptly in rocky cliffs, 25 to 30 meters high. The artillerymen stationed at this site belong to the 2nd battery of the Heeres-Küsten-Artillerie-Abteilung 1260 and are commanded by Oberleutnant Frido Ebeling. The latter, after refusing to fire on a British naval patrol on 22 October 1943, was replaced a few days later by his deputy, Oberleutnant Brotkorb. These men can count on the protection of the infantrymen of the 3rd battalion of the Grenadier-Regiment 726 which is responsible for the protection of the coast between Grandcamp-les-Bains and Vierville-sur-Mer. In addition, on May 23, 1944, fifteen artillerymen from the Werfer-Regiment 84 equipped with machine guns reinforced the strength of the battery.

The word “Hoc” comes from “haugr” in Norois, the language of the Vikings, and which means mound. This toponymy is frequent in the Norman language and particularly in “Cap de la Hague” and “Saint-Vaast-La-Hougue”. The Americans, by copying the maps, made a typographical error which transformed “Hoc” into “Hoe” on many cards and reports still accessible today.

For the Allies, it is necessary to seize this battery to clear the beaches (Omaha and Utah) of the threat that these guns makes weigh on them. Such is the mission entrusted to an American unit, the Provisional Ranger Group. The Pointe du Hoc is subject, in the days and months before the landing, of massive bombing. The position, at the top of the cliff, remains difficult to conquer.

The proposed tactics for storming the Pointe du Hoc strongpoint:

Convened five months earlier by General Eisenhower, Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder, a former Texas farmer, learns that the 5th Corps of General Bradley’s 1st Army must storm the area codenamed Omaha Beach. Looking at the aerial photographs of Pointe du Hoc, he first thinks of a joke from the Allied command by discovering this German battery, heavily protected by bunkers and the ramparts of high cliffs. But Bradley, coming to inform him of the future mission, is not there to laugh.

If at 7 o’clock Rudder has not launched a flare indicating the capture of the point of the Hoc, the 500 Rangers reinforcements will be sent directly to Omaha Beach, Charlie sector.

But just days before the launch of Operation Overlord, allied reconnaissance flights and information from the French resistance confirm that the six guns have been removed: instead, four bunkers are under construction, with no weapons listed. These data were transmitted to the cartographers who replaced in May 1944 the pieces of artillery by casemates “U/C”: “under construction” (in French: under construction). But if the tip of the Hoc is a priori no longer a threat, the Rangers must nevertheless continue their efforts towards the Maisy batteries, their secondary objective. At the end of the day, they must settle in the area of Osmanville, about sixteen kilometers away.

Extract from the order of operation given to the Rangers: “Destroy the coastal defenses of Hoe Point (sic) and the tip of the Breakthrough, and flank keep the assault on Omaha. Supported by dismounted elements, seize the batteries of Grandcamp and Maisy. Then operate against enemy positions along the coast between Grandcamp and Isigny ” (Operation Order of March 26, 1944 signed by Major General Gerow commanding the V Corps).

If at 7 o’clock Rudder did not launch a flare signaling the capture of Pointe du Hoc, the 500 reinforcements will be sent directly to Omaha Beach, Charlie Sector.

But just days before the launch of Operation Overlord, allied reconnaissance flights as well as information from the French resistance confirmed that the six guns were removed: instead, four bunkers were under construction, with no weapons listed. These data were transmitted to the cartographers who replaced in May 1944 the artillery guns by casemates “U/C”: “under construction”. But if the Pointe du Hoc is no longer a major threat for Operation Overlord, the Rangers must nevertheless continue their efforts towards the Maisy batteries, their secondary objective.

Extract from the operation order given to the Rangers: “The 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions are attached to 1st Division. They will destroy coastal defense batteries at Pointe du Hoe (!) by simultaneous direct assault up the cliffs between Pointe-du-Hoie and Pointe-de-la-Percée and by flanking action from Beach “Omaha”. They will then, assisted by elements of the assault force, capture enemy batteries at GRANDCAMP and MAISY. Thereafter to operate against enemy positions along the coast between Grandcamp and Isigny” (Operation Order of March 26, 1944 signed by Major General Gerow, commander of the V Corps).

The course of the assault:

On the deck of SS Ben My Chree, on June 6, 1944, James E. Rudder turned to his men and said, “Now listen … Rangers, show them what you are worth. Good luck guys! Demolish them … Depart in five minutes.” The 261 men, splashed by water, affected by seasickness, loaded with their equipment, sail in the L.C.A. type landing craft to the cliffs, hidden by smoke from explosions, fires and by the smoke screen protecting the allied armada. A team is in charge of seizing the Pointe de la Percée, east of Pointe du Hoc, surmounted by a German radar site.

But the current is strong. The landing craft are deported to the east and, a few dozen meters before reaching the coast, Rudder realizes that the cliff towards which they are heading is not the right one… The landing craft assigned to the transport of the soldiers having to disembark at the Pointe du Hoc turn around and sail along the cliff towards the west. Caught under the fire of automatic weapons and mortars, they finally arrive with a view to their objective: it is 7 hours. At that moment, the Allies on the boats, not having seen the flare signaling the taking of the cliff, imagine that the operation is a total fiasco. The 500 Rangers supposed to reinforce Rudder and his men are then directed towards Omaha Beach, where the landing has already begun.

The Germans, for their part, had thirty minutes to recover after the bombardment, to join the bunkers, to establish a defensive system, to rearm themselves. And they waited firmly with weapons and grenades with these soldiers who are approaching their position. The current and the waves flow a L.C.A.: there is only one survivor, the other Rangers disappearing at sea, dragged by their equipment. The German machine-guns crackle and pour an iron rain which falls on the landing craft. Some take water: a L.C.A., carrying exclusively ammunition destined for the Rangers, explodes in a stunning din, projecting shrapnels in the vicinity. The first L.C.A. reaches the pebble beach to the east of the Pointe: the precipitation caused by the initial navigation error prevents the Rangers from climbing the cliff on either side of the Pointe. They all head towards the east side. The American Rangers rush out, discovering a beach five to six meters wide already dug by numerous mortar shells.

The first corps fell on the pebbles, while the survivors threw grapples and ropes through mortars, while at the same time the naval artillery supported them as close as possible. But the water weighed down the ropes and grapples fell on the beach. Some people then decide to climb the cliff with their hands, digging steps in the rock with their dagger. The Germans pour a rain of grenades on the thin strip of beach and water it with the bursts of machine guns.

The Rangers use the few ropes that the Germans have not had time to cut to reach the summit of the cliff. A few minutes later, the first American soldiers headed for the bunkers and discovered a lunar space, dug by the bombs. The Germans disappeared but snipers opened fire. These snipers use the holes dug by the bombs to get closer to the Rangers.

Within fifteen minutes, the Pointe is taken and secured by the Americans. According to information provided by Allied intelligence, the Germans withdrew the 155-mm artillery pieces several weeks before landing. The latter were replaced, following multiple bombings and pending the construction of all concrete shelters, by wooden poles whose purpose was to deceive the Allied reconnaissance planes. On June 6, 1944, only four casemates had come out of the ground and were still under construction.

Once the surprise effect gone, Lieutenant-Colonel Rudder organizes the defense of the piece of land he controls. He enters into communication with the armada shortly after 8 am, from his command post behind the aircraft defense bunker to the east of the battery: “This is Rudder, the Hoc is under control… I need reinforcements and ammunition… Heavy losses…! ” A little later, he was told, “Good job. Sorry for the reinforcements, all the Rangers have already landed in Omaha.“

The losses are indeed very high, but Rudder must do with it. Theoretically, he must go to Osmanville to flank guard the landing operations in Omaha while neutralizing the various points of German support encountered along the way. But the amphibious assault of the 1st Infantry Division and the 29th Infantry Division between Vierville-sur-Mer and Colleville-sur-Mer unfolds badly: the American infantry are set on the edge of the beach and fail to break through the line head on. Only a few elements of the 5th Ranger Battalion manage to reach the Pointe du Hoc from the afternoon of June 6, crossing the seven kilometers of grove through the enemy positions. Rudder makes the decision to wait for reinforcements from Omaha and firmly defends the point of the Hoc. He nevertheless launched patrols towards the road from Grandcamp to Vierville-sur-Mer, so as to block any German reinforcements that would move east.

1st Sergeant Leonard G. Lomell and Staff Sergeant Jack E. Kuhn, belonging to Company D of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, discover about one kilometer south of the battery five pieces of field artillery, camouflaged behind a hedge. Dozens of German soldiers are present, about a hundred meters further south. The young American sergeant gives his orders: his comrade must observe the German positions while he launches two grenades on the first two pieces. These grenades, also called “thermites”, produce an aluminothermic chemical reaction that melts the surrounding metal. Lomell destroys the sighting systems of the other howitzers with the butt of his Thompson submachine gun, wrapped in his jacket to limit the noise. After successfully completing this operation, the patrol retraces its steps to retrieve additional grenades in order to complete the work. Ten minutes later, the action is over and the two Rangers retreat immediately.

The young American sergeant gives his orders: his comrade must observe the German positions while he throws two thermal grenades on the first two guns. These grenades, also called “thermites”, produce an aluminothermic chemical reaction that melts the surrounding metal. Lomell destroyes the sighting systems of the other howitzers with the butt of his Thompson gun, wrapped in his jacket to limit the noise. After successfully completing this operation, the patrol retraces to recover additional grenades to complete the work. Ten minutes later, the action is over and the two Rangers go back to their lines.

Offshore warships fire a barrage around US-controlled areas. Night falls and the Germans organize a counterattack. They infiltrate through the American lines and then are pushed back by the Rangers. But the ammunition is going low and the reinforcements are still not there. In addition, many Rangers are taken prisoners since they can not hold hermetic defenses and are often taken to backhand. An explosion stronger than the others is suddenly heard: a Ranger has just blown up the German ammunition depot.

In the early morning of June 7, Rudder makes another terrible observation: the ammunition and provisions are insufficient to hold this siege. And the 116th infantry regiment is still not there! But they have hold, these are the orders. The 116th infantry regimentis indeed delayed by a very strong resistance, in Vierville-sur-Mer and on the road towards Pointe du Hoc. Nobody knows the date, the time of their arrival to reinforce the Rangers.

The German defense is concentrated to the west of the Pointe, around the western anti-aircraft bunker, reinforced by the presence of a 88 mm gun. Rudder abandoned the idea of seizing it, having already lost twenty soldiers to try to seize this German resistance point. Everywhere else, many snipers injure and kill Rangers.

The second night falls on Pointe du Hoc since this piece of land belongs half to the American soldiers who cling to it with their nails. Reinforcements have not yet arrived, fatigue is gaining (many have not closed their eyes for two days), ammunition and food are practically exhausted and the number of Rangers still able to fight is decreasing. In order to put an end to the American resistance, the Germans launch no less than three counter-attacks on the sector held by the Rangers. Little by little, the American resistance falls. In the early morning of June 8, 1944, when the Germans launched what was to be their final blow for the enemy, the American tanks of the 116th regiment finally arrived at Pointe du Hoc, along with the infantry. The Rangers are now reinforced.

Assessment of the Pointe du Hoc assault

Of the 261 combatants engaged at Pointe du Hoc, few survivors were not injured. The end of the fighting on June 8 only marks the fulfillment of part of the orders given to the American commandos who must now move as quickly as possible to the Maisy’s two strongpoints (Stp 83 and Stp 84) and clean up the other German strongpoints as far as Osmanville.

The 500 Rangers who landed along the Côte d’Or on June 6 at around 7:30 am met a very strong resistance on the beach. They splitted into two groups: one with about fifty soldiers landed as planned on the Charlie sector (Vierville-sur-Mer), the other farther east to avoid the German defenses forbidding any approach. Indeed, of the fifty soldiers engaged on Charlie, there were only ten to survive the landing while in the east, the losses were much lower.

The courage of the Rangers on Omaha Beach is exemplary and these men, especially on Charlie, are opening ways accross the defenses at the cost of incredibly high losses like all American units on Omaha.

Nowadays, the motto of the Rangers, the elite unit of the United States Army, is “Rangers, lead the Way!“. This motto is first pronounced by General Cota on Charlie, to encourage these Rangers to help infantrymen of the 29th infantry division, also suffering many losses.