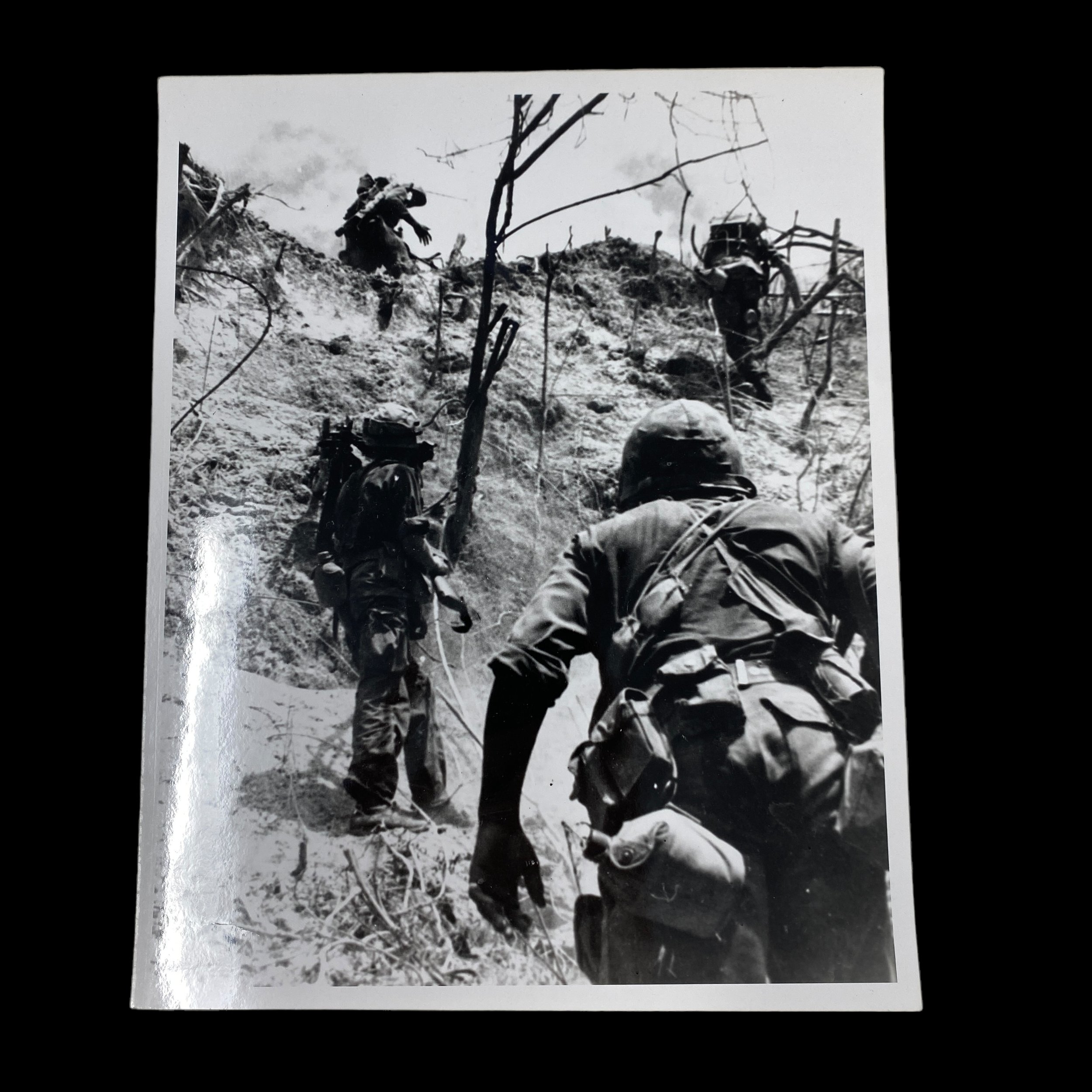

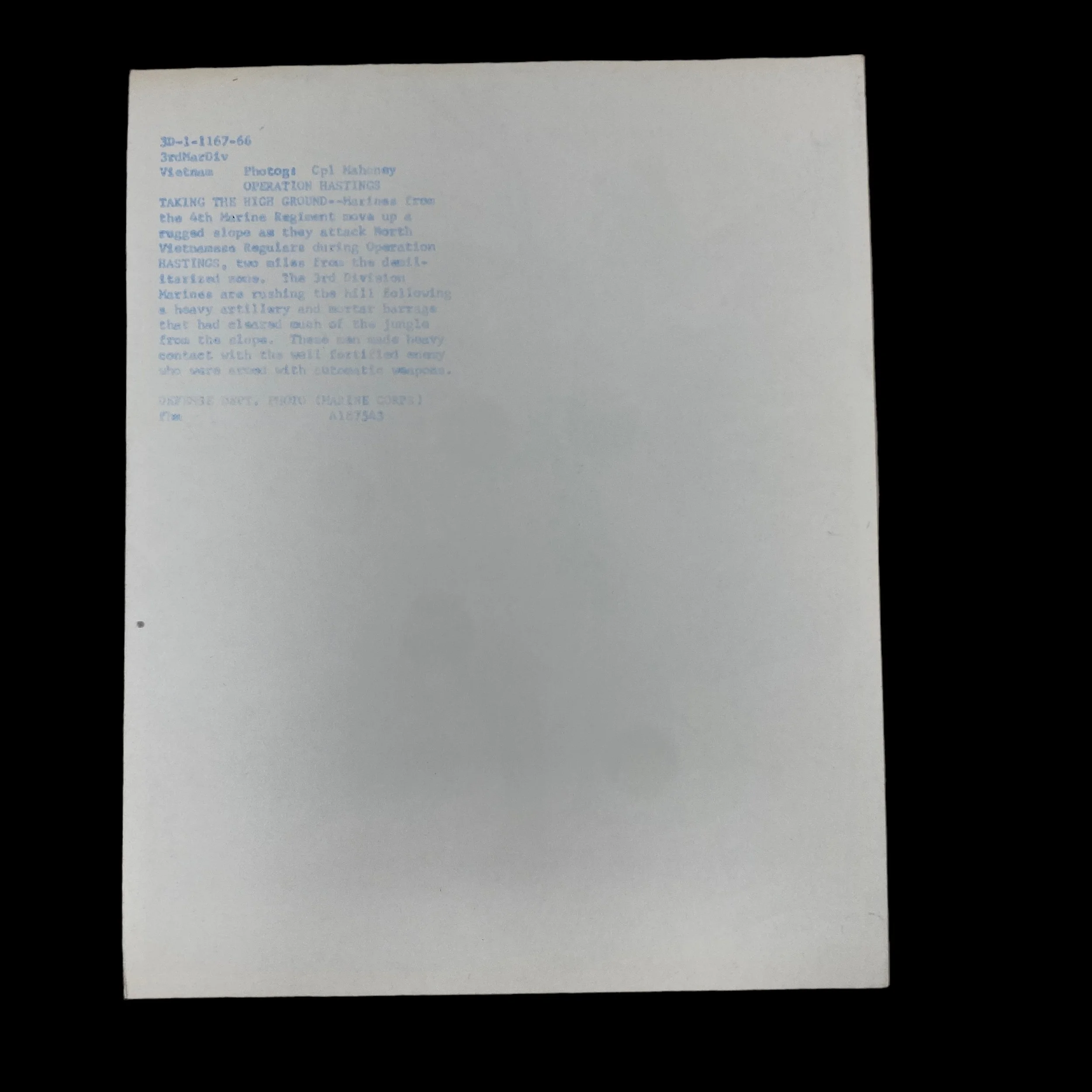

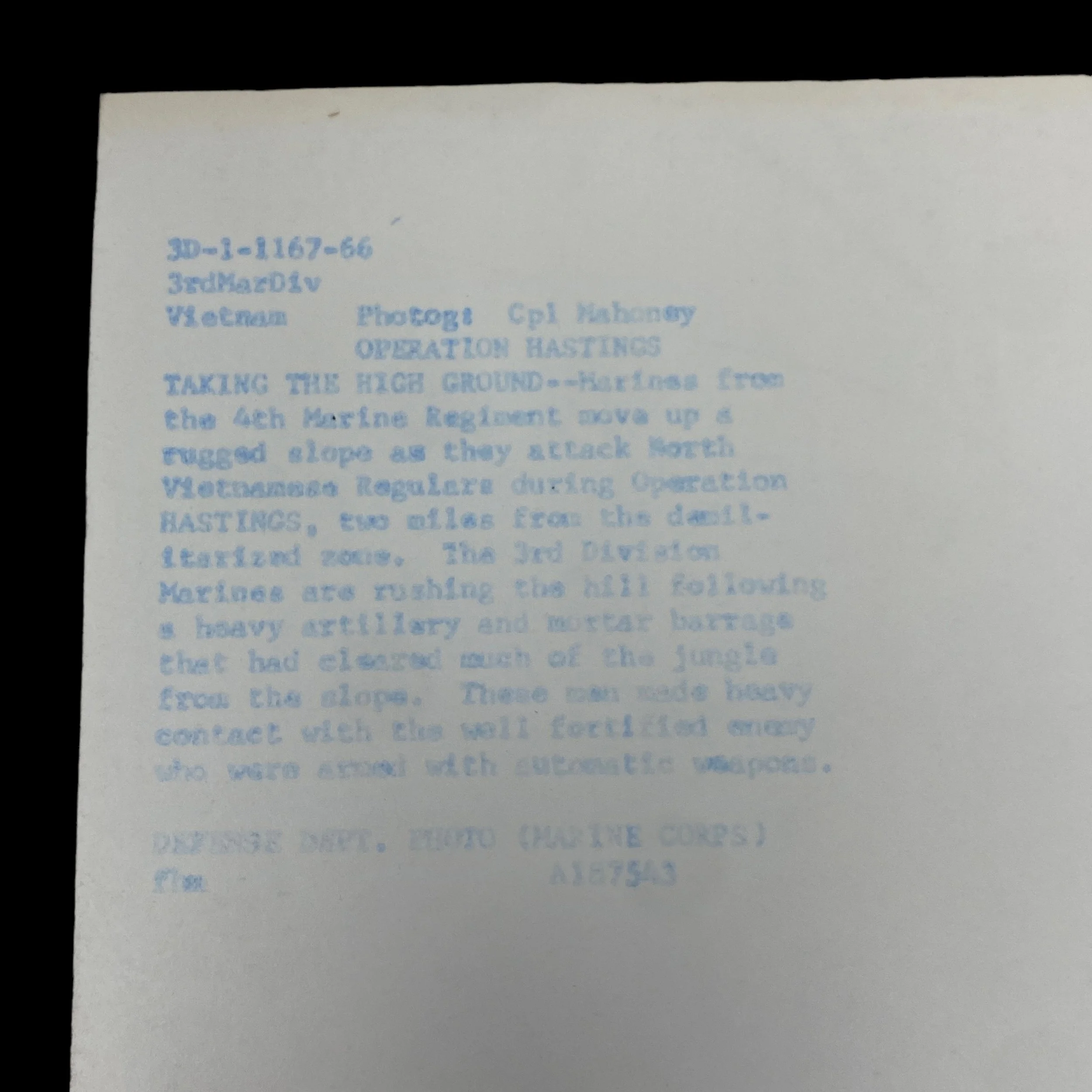

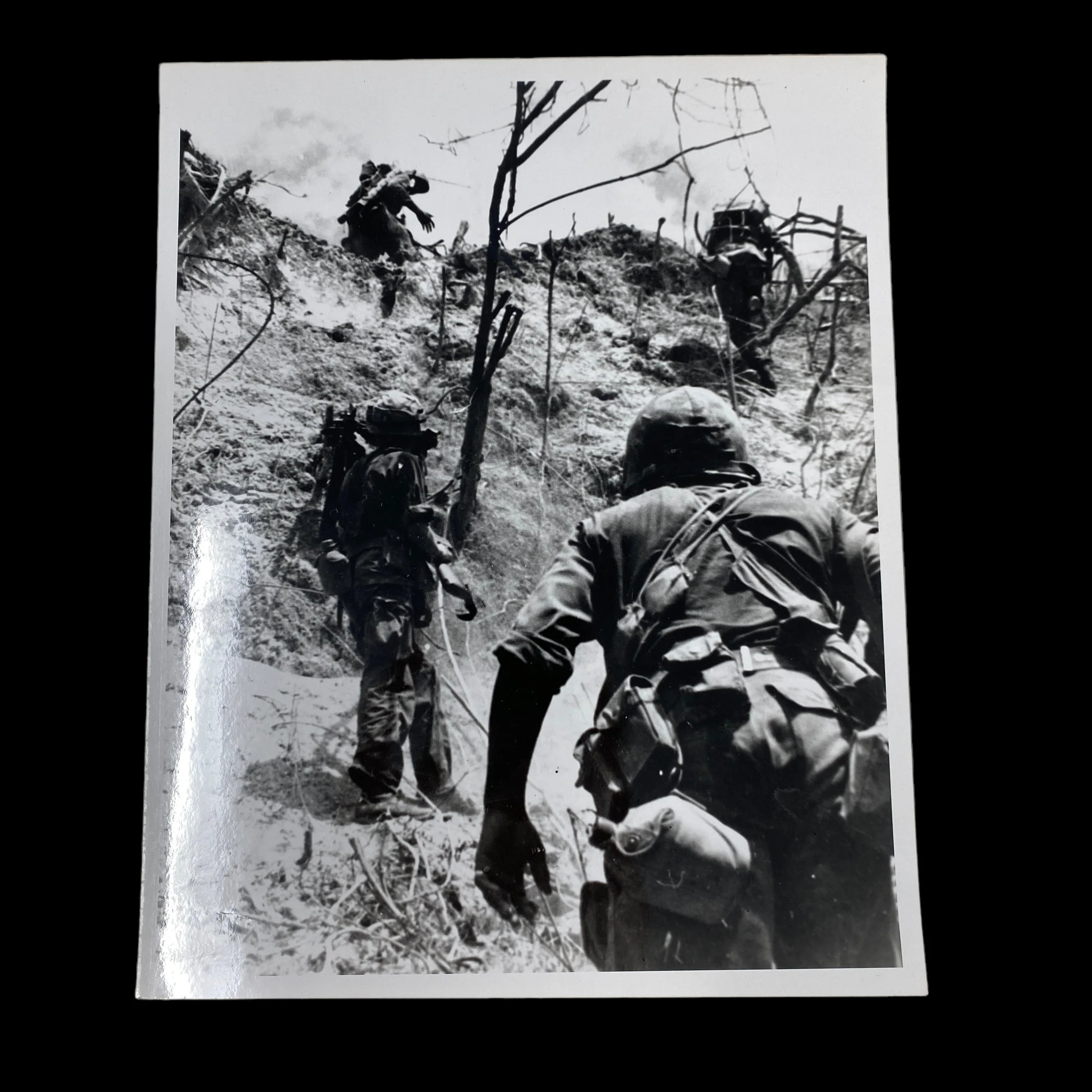

VERY RARE! 1966 "Operation Hastings" 3rd Marines Cpl. Mahony 'TYPE ONE' Original Defense Department (USMC) Combat Photograph*

VERY RARE! 1966 "Operation Hastings" 3rd Marines Cpl. Mahony 'TYPE ONE' Original Defense Department (USMC) Combat Photograph*

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

*THIS IS ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS AND WELL-RECOGNIZED/FAMOUS VIETNAM WAR COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHS FROM OPERATIONS HASTINGS WHICH IS WHY THIS TYPE-ONE IS NOT DISCOUNTED.

Size: 8 x 10 inches

This original and museum-grade Vietnam War is an extremely rare TYPE ONE (Defense Department) 3rd Marine Division combat photograph taken by Cpl. Mahony during Operation Hastings.

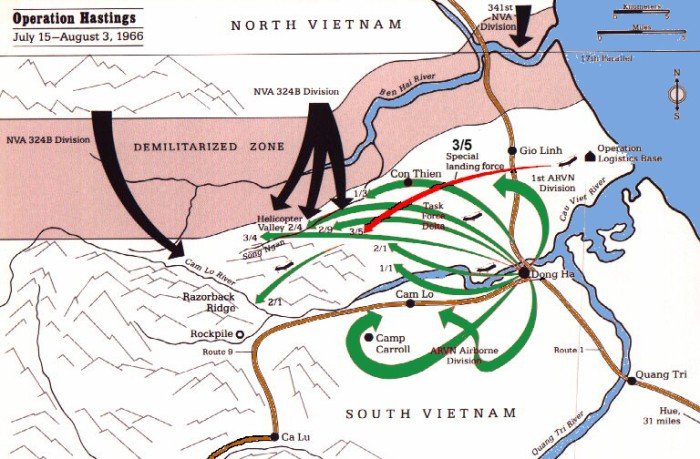

Operation Hastings was a military operation that took place from July 15–August 3, 1966, in the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone. It was one of the largest operations of the Vietnam War, involving 8,000 Marines and 3,000 South Vietnamese troops.

Type One photographs are very rare as they are the first high-gloss prints from original combat negative camera images and contain the original marker stamps on the backside noting the photography information. Original government Vietnam War Defense Department (USMC) combat photographs are very rare and rarely come to the public sector.

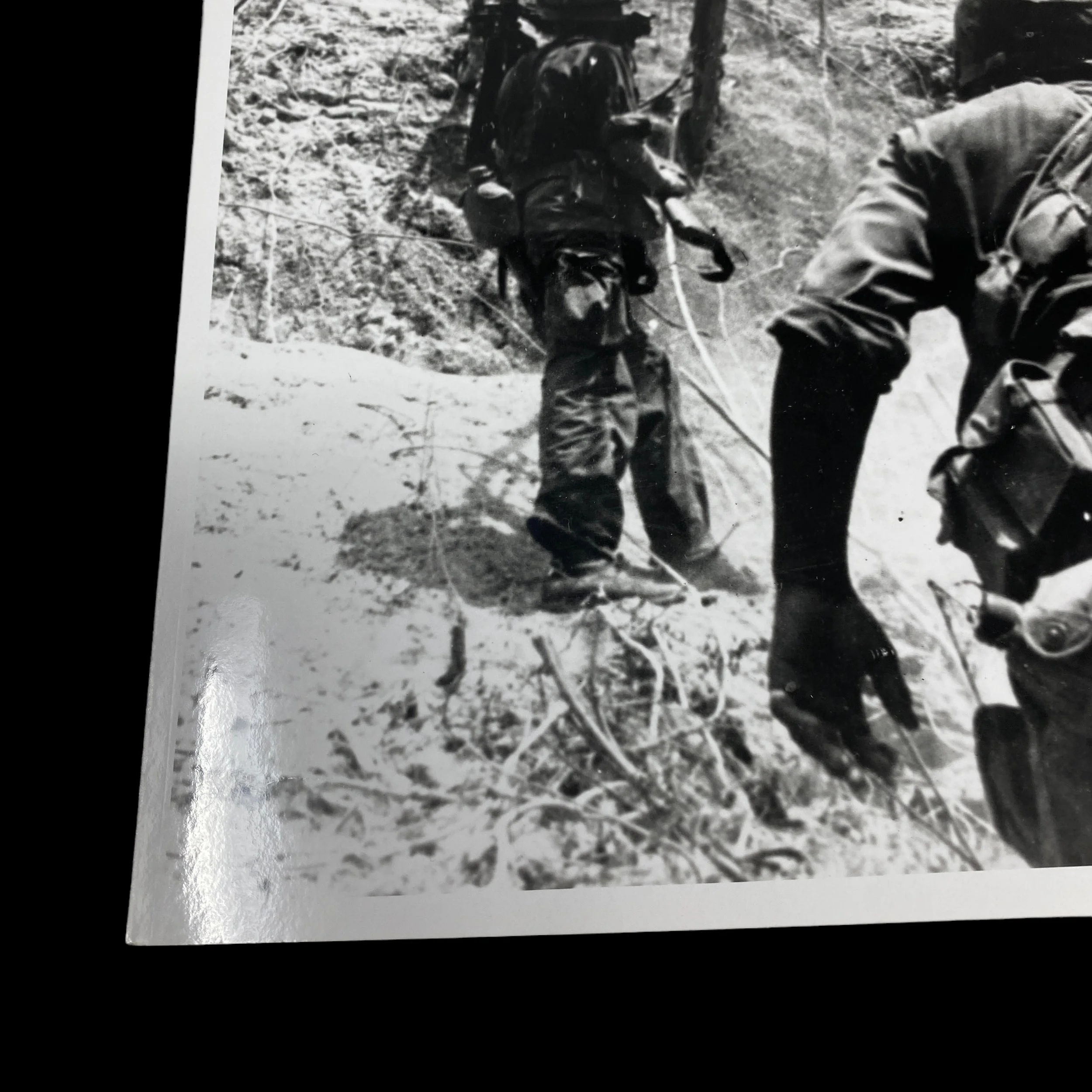

On the backside of the TYPE ONE combat photograph it notes “Taking the high ground, Marines from the 4th Marine Regiment move up a rugged slope as they attack North Vietnamese regulars during Operation Hastings 2 miles from the Demilitarized Zone. The 3rd Division Marines are rushing the hill following a heavy artillery and mortar barrage that had cleared much of the jungle from the slope. These men made heavy contact with the well-fortified enemy, who were armed with automatic weapons.

Operation Hastings:

By early 1965, South Vietnamese forces had suffered a series of significant defeats. Despite spending much of the already decade-long war fighting an irregular opposition, the tide seemed to be turning, culminating in resounding defeats at the Battles of Bình Giã and Đồng Xoài. As a response to this shift in the fortunes of war, the United States unilaterally deployed 3500 Marines to South Vietnam. Initially, these Marines were tasked to assist in the defence of the American ally and ensure neither Viet Cong (VC) nor the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) could conduct success conventional operations against the South. These troops were quickly reinforced, and over 200 000 Marines would be on the ground by the end of the year. Army and other forces totaled thousands more. The American plan was fairly simple: initially, American forces, supported by her free world allies and South Vietnam, would commit enough forces to put a stop to North Vietnamese advances and seize the initiative. Following this, the US would conduct their own offensive operations, pushing the North Vietnamese forces out of key areas and reducing their strength. Finally, if necessary, American forces planned to hunt down remaining enemy combatants and destroy their ability to fight, ensuring the conditions for a safe and secure Vietnam. As we know, these plans did not unroll exactly as the United States would have liked.

By May of 1966, an ad hoc demilitarized zone (DMZ) had been established dividing North and South Vietnam. This did not stop a company-sized force of reconnaissance soldiers from PAVN Division 324B from slipping across the DMZ in the early morning of 17 May. Their mission was to act as scouts for the ten-thousand strong division as it readied for an advance into Quang Tri province, at the time part of South Vietnam and defended by the 1st Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam’s (ARVN) I Corps. An ongoing conflict between Buddhists and government forces in the South that paralyzed military forces in the province convinced Division 324B’s commander, General Nguyen Vang, that the time had come to strike. In order to set the conditions for a successful advance, VC units local to Quang Tri had been contracted to establish stores of food and ammunition around the province. When his reconnaissance elements arrived, General Vang learned that the supply caches were few and far between. With Division 324B poised on the border, the attack was held up by a matter of weeks to allow food to be requisitioned from North Vietnam.

OAs the North Vietnamese held just shy of the DMZ, American and South Vietnamese elements monitored and speculated on their intentions. While the logic of a large-scale assault into Quang Tri was acknowledged, General William Westmoreland, then commander of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), demanded a better picture of the North’s actions and intentions, and, in his words, “…there was no better way to get at it than by sending in reconnaissance elements in force.” There were also concerns at tactical levels about the feasibility of PAVN logistical support to a division-sized offensive and theories that the 324B’s build-up may be a feint designed to vex Quang Tri-based ARVN and US Marine forces. On the evening of 1 July, a small Marine reconnaissance force was sent to observe suspected enemy locations a few miles south of the DMZ. After coming into contact almost immediately upon arrival, the Marines received air support from A-4 Skyhawks and UH-1C Heavy Hogs, allowing them to escape. Further reconnaissance of the area confirmed large masses of soldiers, as well as a host of fortifications. The 324B had entered South Vietnam.

As the North Vietnamese held just shy of the DMZ, American and South Vietnamese elements monitored and speculated on their intentions. While the logic of a large-scale assault into Quang Tri was acknowledged, General William Westmoreland, then commander of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), demanded a better picture of the North’s actions and intentions, and, in his words, “…there was no better way to get at it than by sending in reconnaissance elements in force.” There were also concerns at tactical levels about the feasibility of PAVN logistical support to a division-sized offensive and theories that the 324B’s build-up may be a feint designed to vex Quang Tri-based ARVN and US Marine forces. On the evening of the 1st of July, a small Marine reconnaissance force was sent to observe suspected enemy locations a few miles south of the DMZ. After coming into contact almost immediately upon arrival, the Marines received air support from A-4 Skyhawks and UH-1C Heavy Hogs, allowing them to escape. Further reconnaissance of the area confirmed large masses of soldiers, as well as a host of fortifications. The 324B had entered South Vietnam.

In response, MACV and the local Marine commanders quickly created and launched Operation Hastings on the 7th of July. It was designed to locate, engage and push PAVN forces back across the DMZ. The operation would be the largest in Marine Corps history at the time and included the mobilization of over 8000 Marines and 3000 ARVN soldiers, supported by a wide array of artillery, naval gunfire, air, and aviation support. Task Force Delta, the task force executing Operation Hastings, would be led by then Brigadier General (later General) Lowell English, at the time Assistant Division Commander of 3rd Marine Division and would see four Marine infantry battalions and one Marine artillery battalion under his command. These Marines would advance across a series of mountains, foothills and jungle, ending in the shadow of The Rockpile, a large and solitary hill dominating the plateau north of the Cam Lo River. Aggressively taking The Rockpile, as well as trailheads leading from Quang Tri across the DMZ into North Vietnam, were deemed the highest priority objectives, in order to quickly and assertively weaken the grip of PAVN forces on the area and set the conditions for American forces to maintain momentum and push them back across the DMZ.

In preparation for the assault, B-52 strategic bombers dropped countless loads of explosives on suspected PAVN positions. Meanwhile further south, American transport aircraft dropped pallets of supplies to supply the Marines that would soon be on the ground. Supported by A-4 Skyhawks and F-4B Phantoms, the Marines inserted via CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters on the morning of the 15th of July. Landing in two drop zones, the first wave of Marines inserted quietly, with the second wave coming under sniper fire from PAVN forces. It was the third wave, though, that represented the first significant losses of the operation. While trying to land in the dense jungle, two CH-46s collided with each other in mid-air and crashed. When a third took evasive maneuvers to avoid them, it hit a tree and also crashed. Later, another helicopter was hit by PAVN anti-aircraft fire and went down in the same area. What was previously known as the Song Ngan Valley had become known, to the Marines of Task Force Delta, Helicopter Valley.

Despite the dark beginning, upon reaching the ground Marines immediately began executing both the task to take The Rockpile and to deny enemy movement through the trail-heads. Movement through the low-ground of Helicopter Valley towards the trail-heads was fairly quick, but those moving to take The Rockpile were hampered by dense, wet vegetation, and progress slowed. Meanwhile, by that evening Marines from the force moving through Helicopter Valley had been surrounded by PAVN forces, and were forced to employed artillery and fast air fires to drive the aggressors off. To reinforce this beleaguered force, the movement to The Rockpile was abandoned and those Marines moved to aid their comrades. By that night, both groups were under fierce PAVN attack, and fighting devolved in some cases to hand-to-hand combat. Despite this, the Marines again held their ground and pushed the North Vietnamese back, inflicting significant casualties in the process.

To compensate for their casualties and delayed progress, another battalion of Marines was deployed, while a reconnaissance force was inserted onto the top of The Rockpile. This capability proved invaluable, supporting surrounding allied efforts by reporting artillery targets throughout the battle. With this support firmly established, the Marines were able to consolidate their forces and establish a blocking line and an assault force, and began moving towards their new objectives on the afternoon of 18 July. As the Marines attempted to bring the fight to the enemy it was instead the PAVN who brought the fight to them, attacking the rearguard which had been left behind to destroy the CH-46s that had been downed in the previous days. Faced with around 1000 charging PAVN soldiers, the Marines held the line, but not before they took around 50 casualties. After having finally driven off the assault through the use of danger-close conventional and napalm airstrikes, the Company was able to withdraw, with both their Officer Commanding and First Platoon Commander being awarded Medals of Honor. The main Marine force was recalled and set up another block to turn back the large PAVN force.

The following week saw many smaller engagements, generally initiated by PAVN forces, and often following procedure first involving artillery and mortar strikes, followed by a fierce assault, then withdrawal. While this frustrated some American commanders, the casualty count was overwhelmingly in their favor. By the end of the month, the bulk of Task Force Delta would be withdrawn from the Area of Operations, predominantly due to poor terrain for helicopter insertions. However, reconnaissance patrols would continue to operate in the region, and the outpost at The Rockpile would continue to be an important artillery observation post. By 3 August, patrols found that the 324B Division had seemingly retreated back across the DMZ, and Operation Hastings was officially brought to an end. Despite at times heavy losses, the Operation proved a tactical, operational, and strategic success for the United States, and was instrumental in the adoption of several new tactics and techniques.