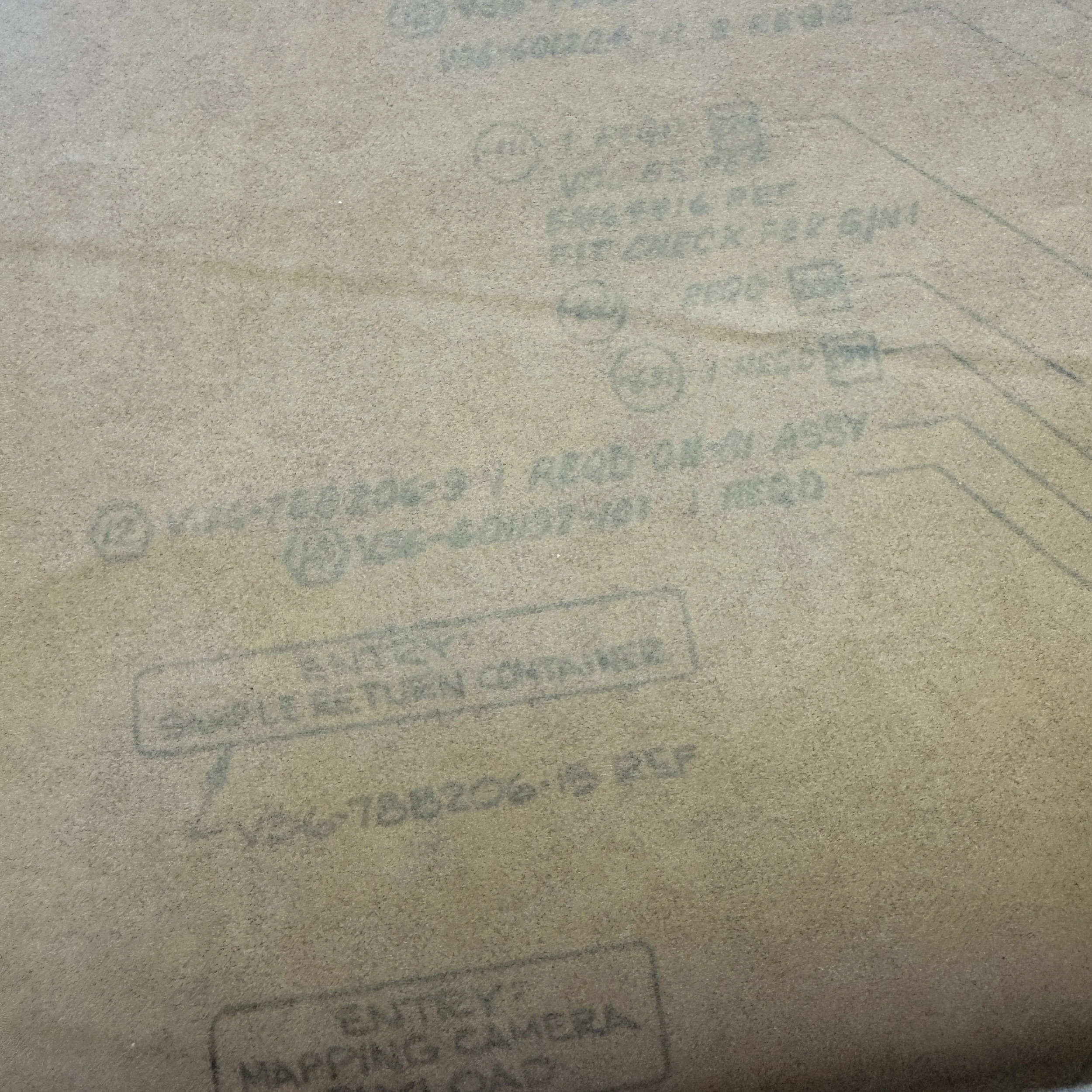

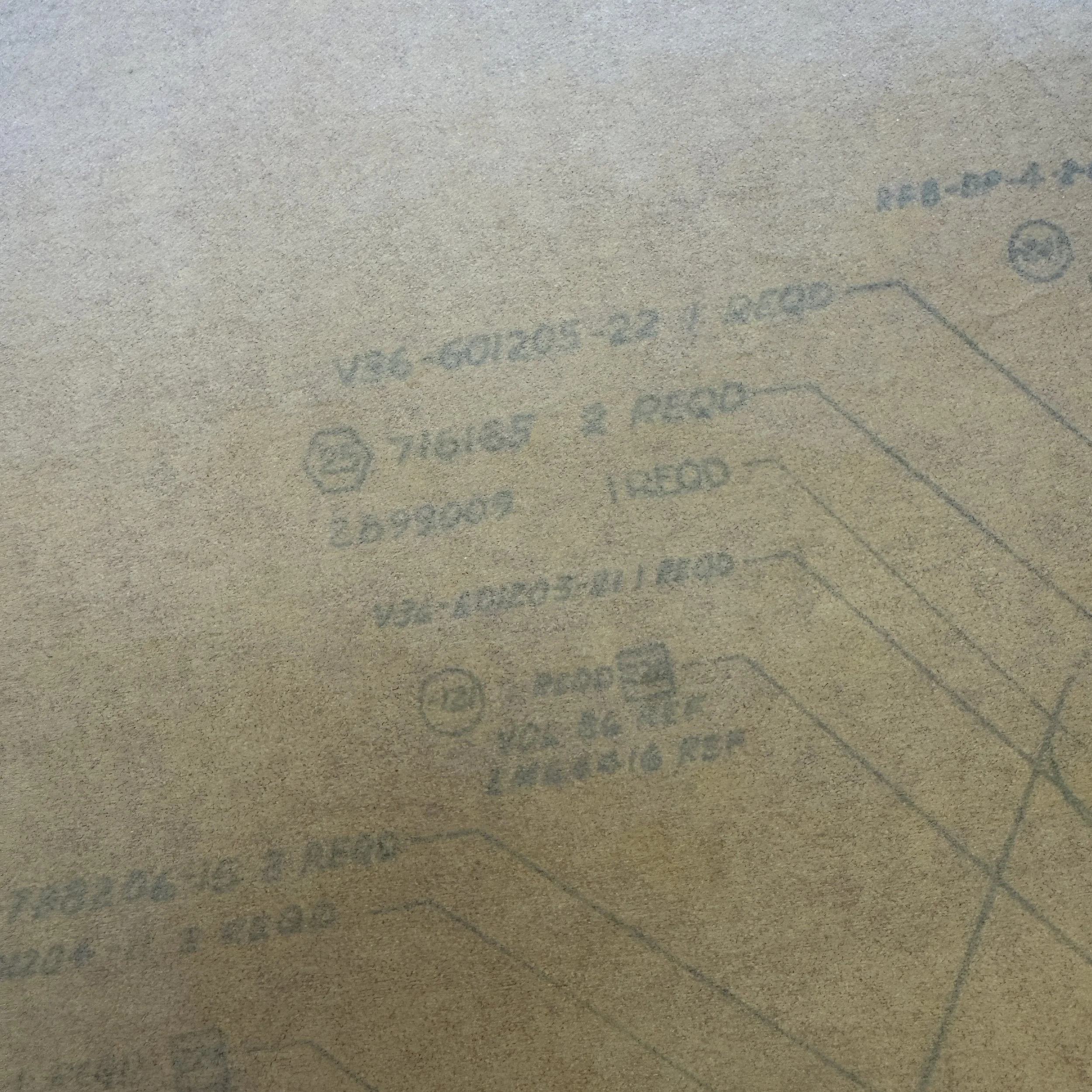

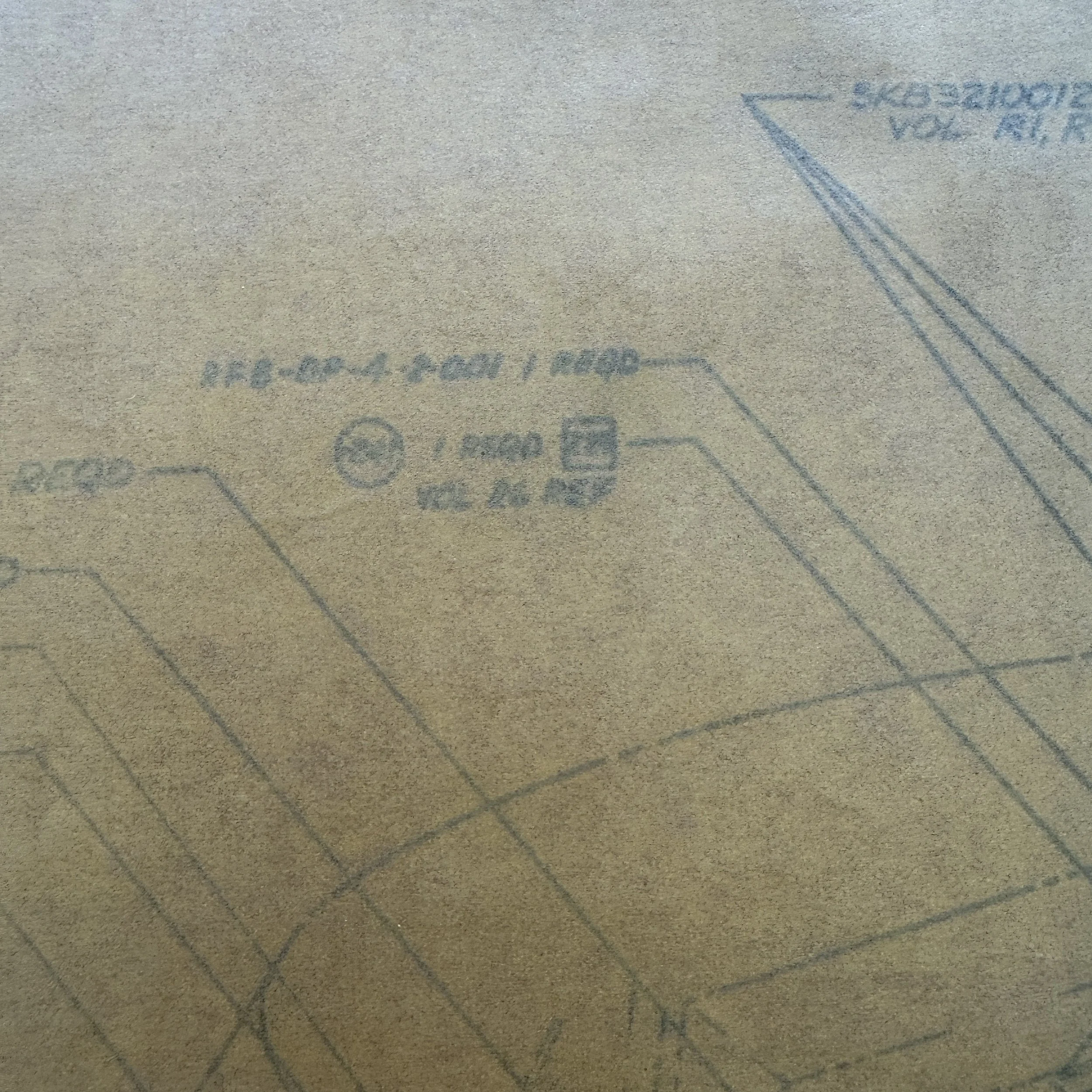

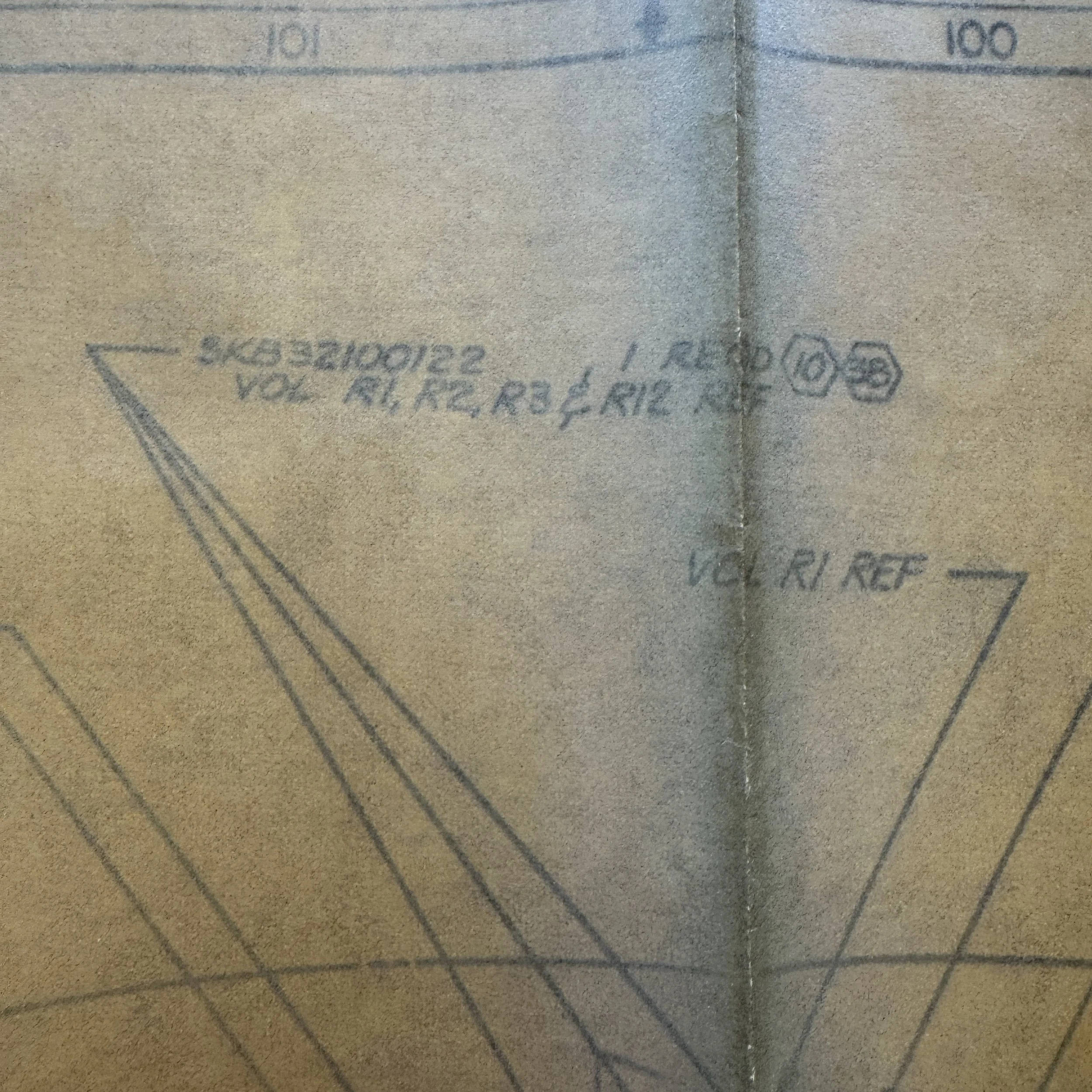

VERY RARE! Original 1971 Apollo 16 NASA Apollo Command Service Module (CSM) Blueprint with NASA Engineer Apollo 16 & 17 Mission CSM Modifications

VERY RARE! Original 1971 Apollo 16 NASA Apollo Command Service Module (CSM) Blueprint with NASA Engineer Apollo 16 & 17 Mission CSM Modifications

Comes with a hand-signed Certificate of Authenticity

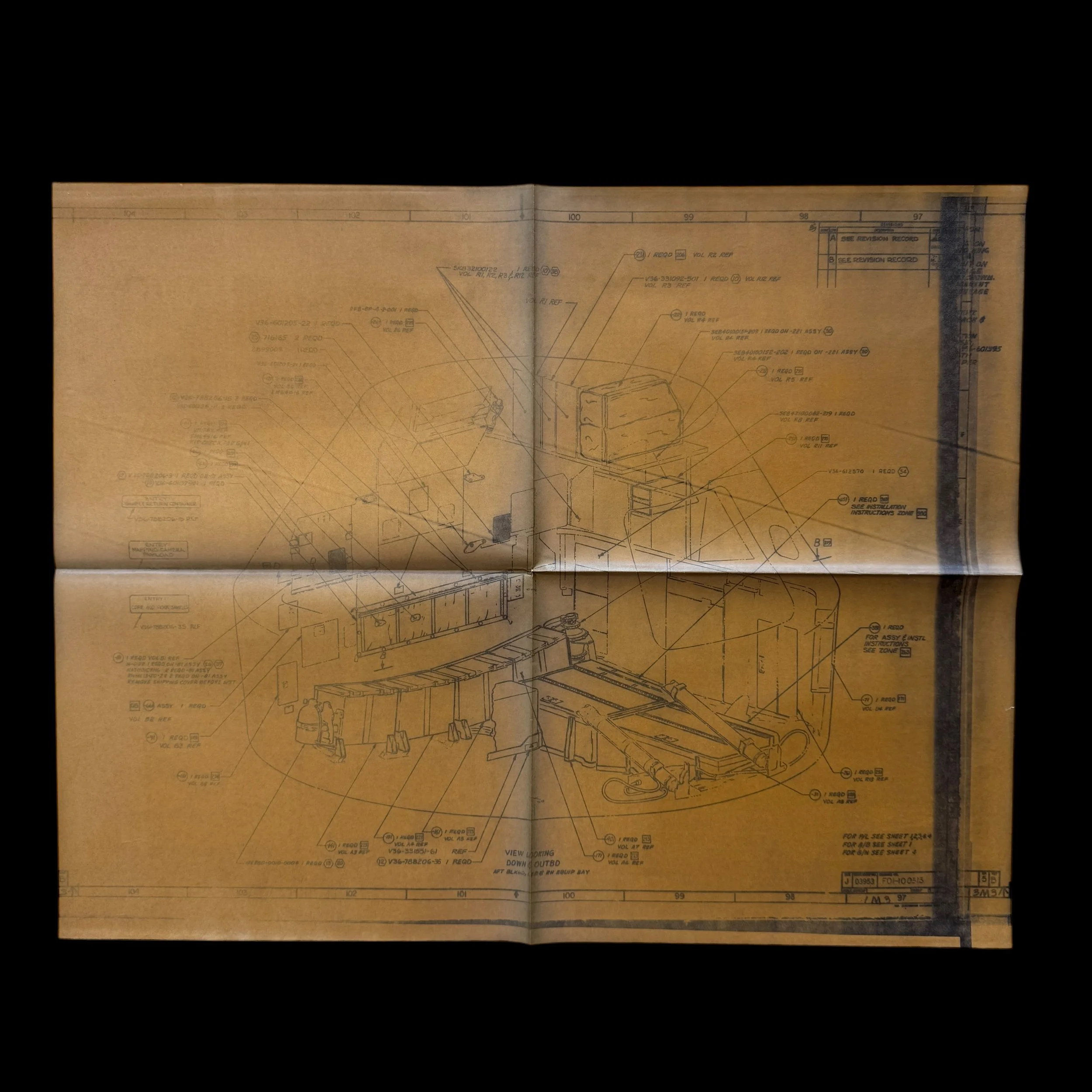

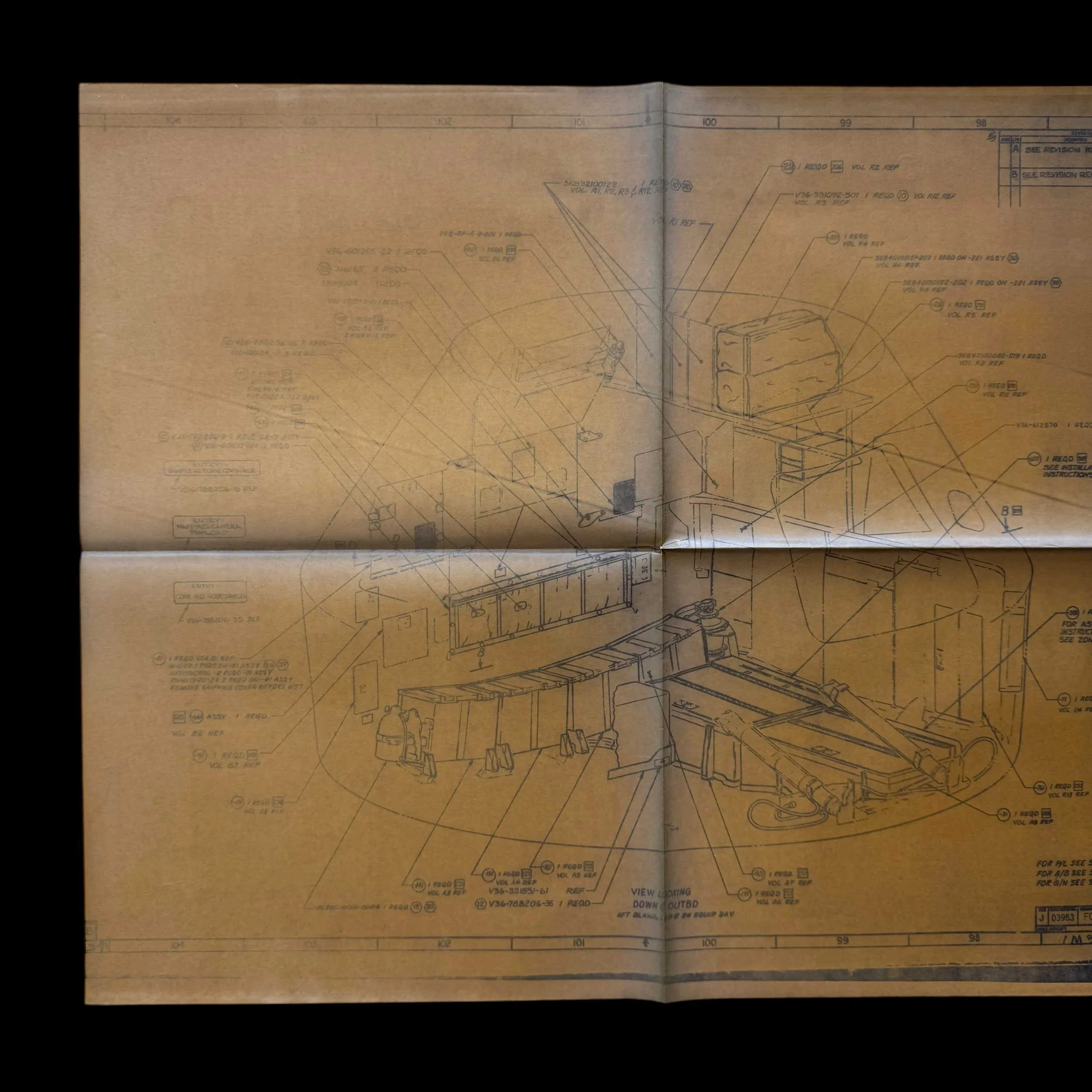

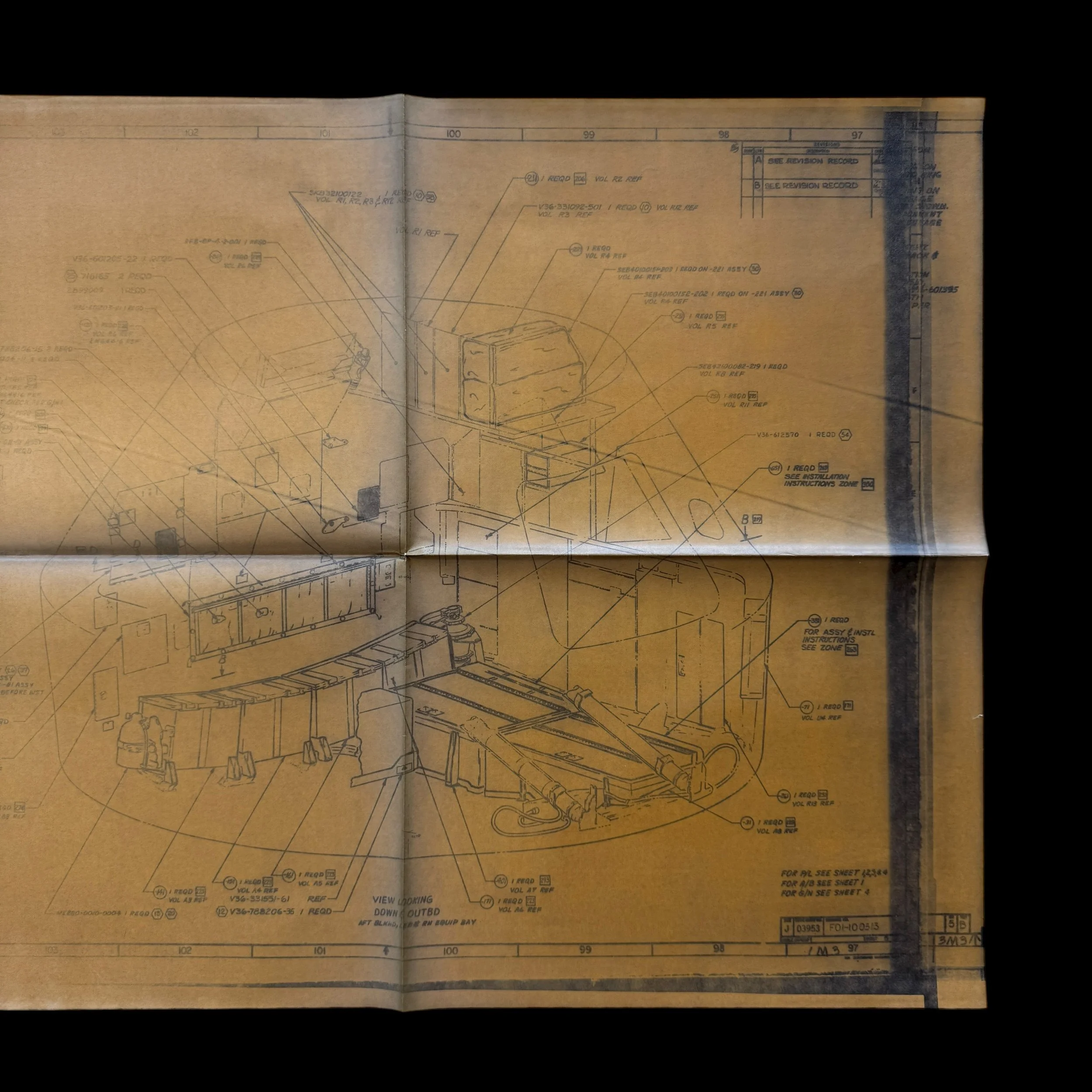

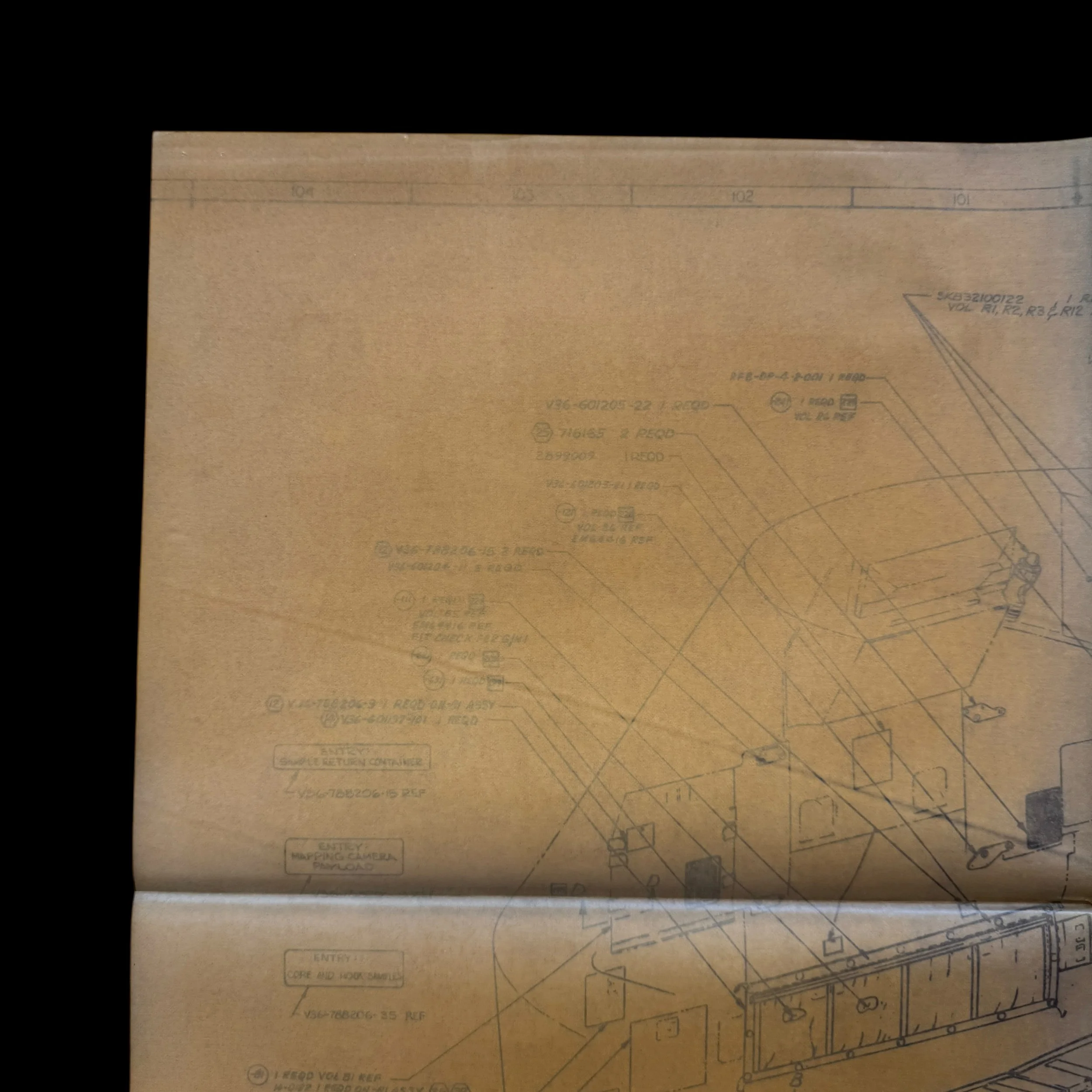

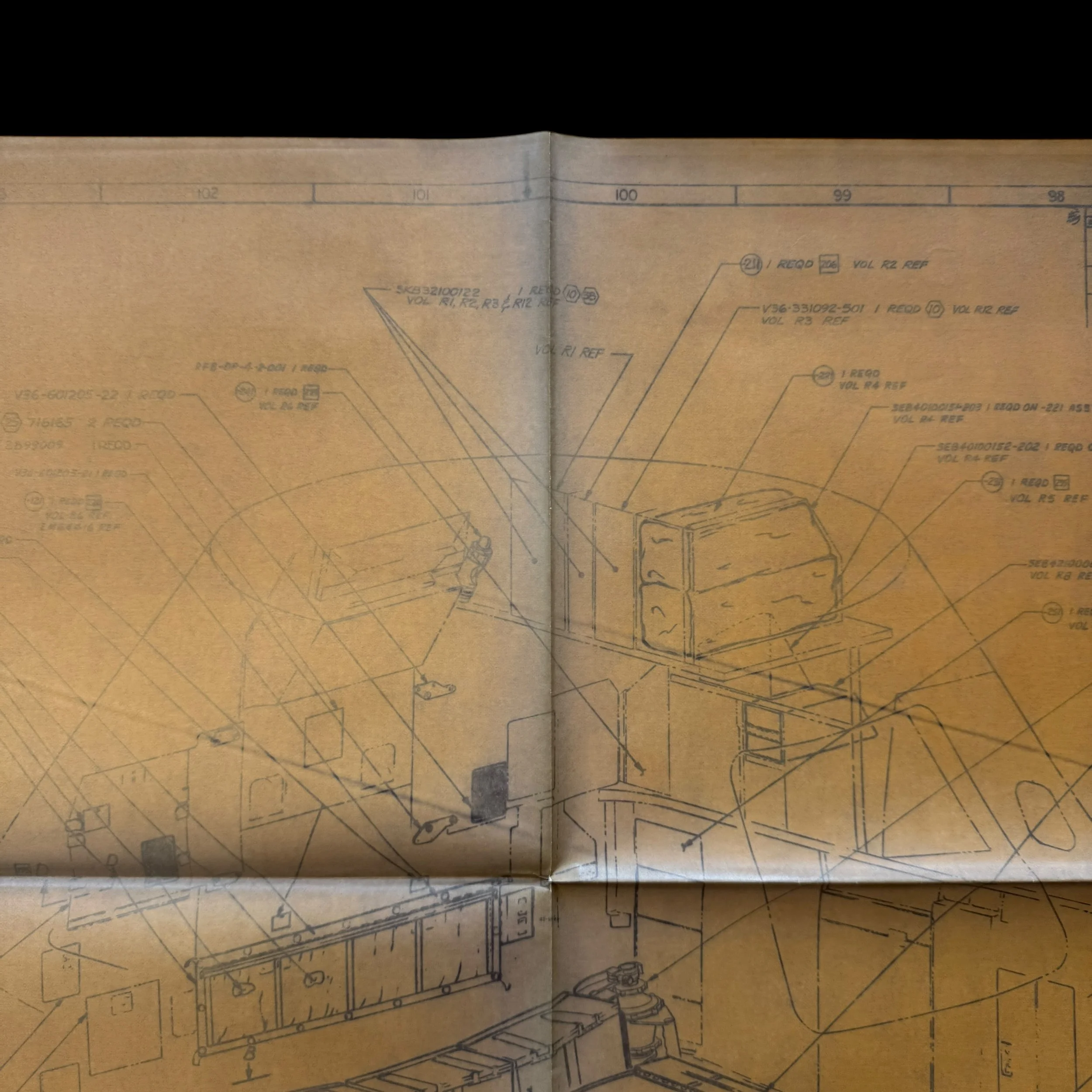

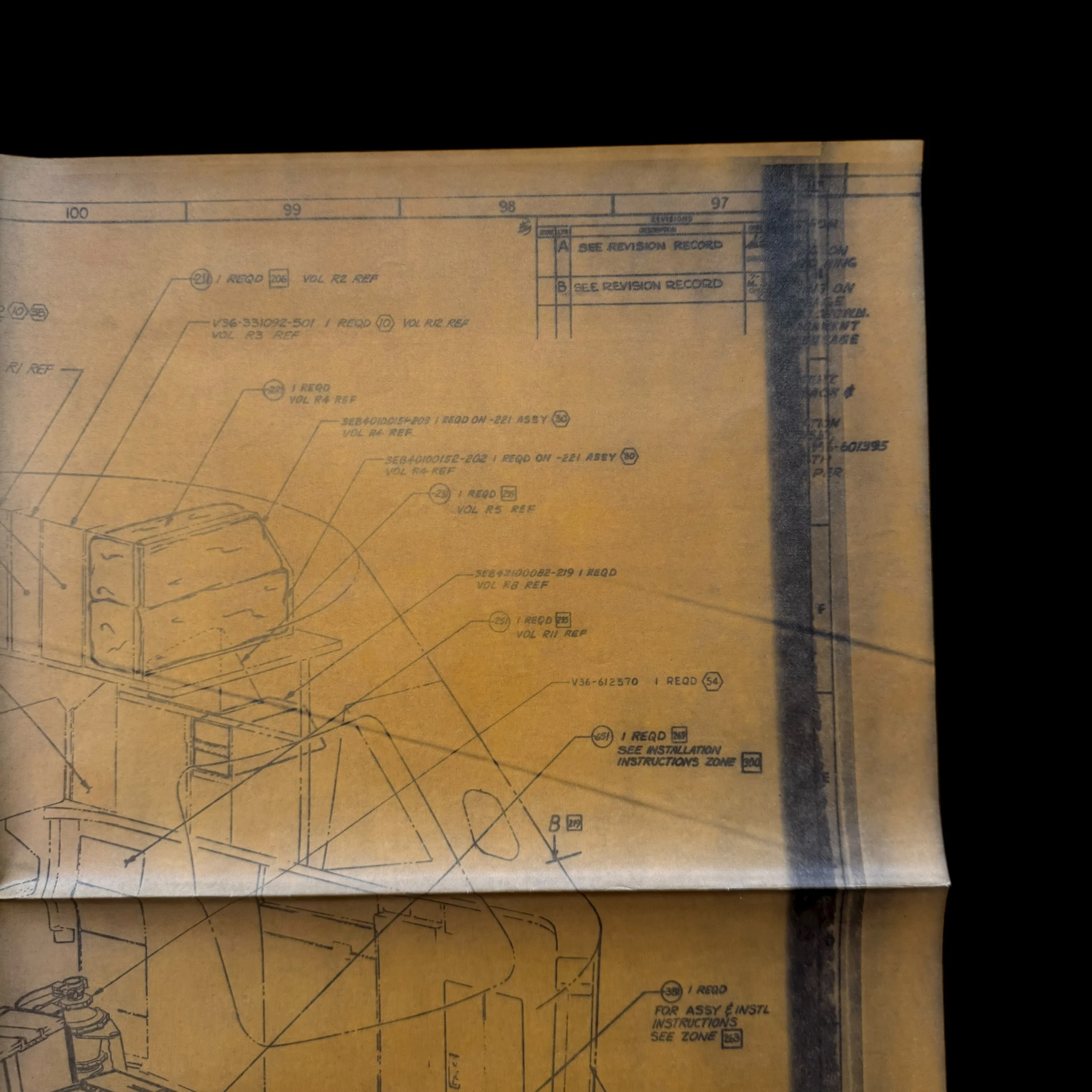

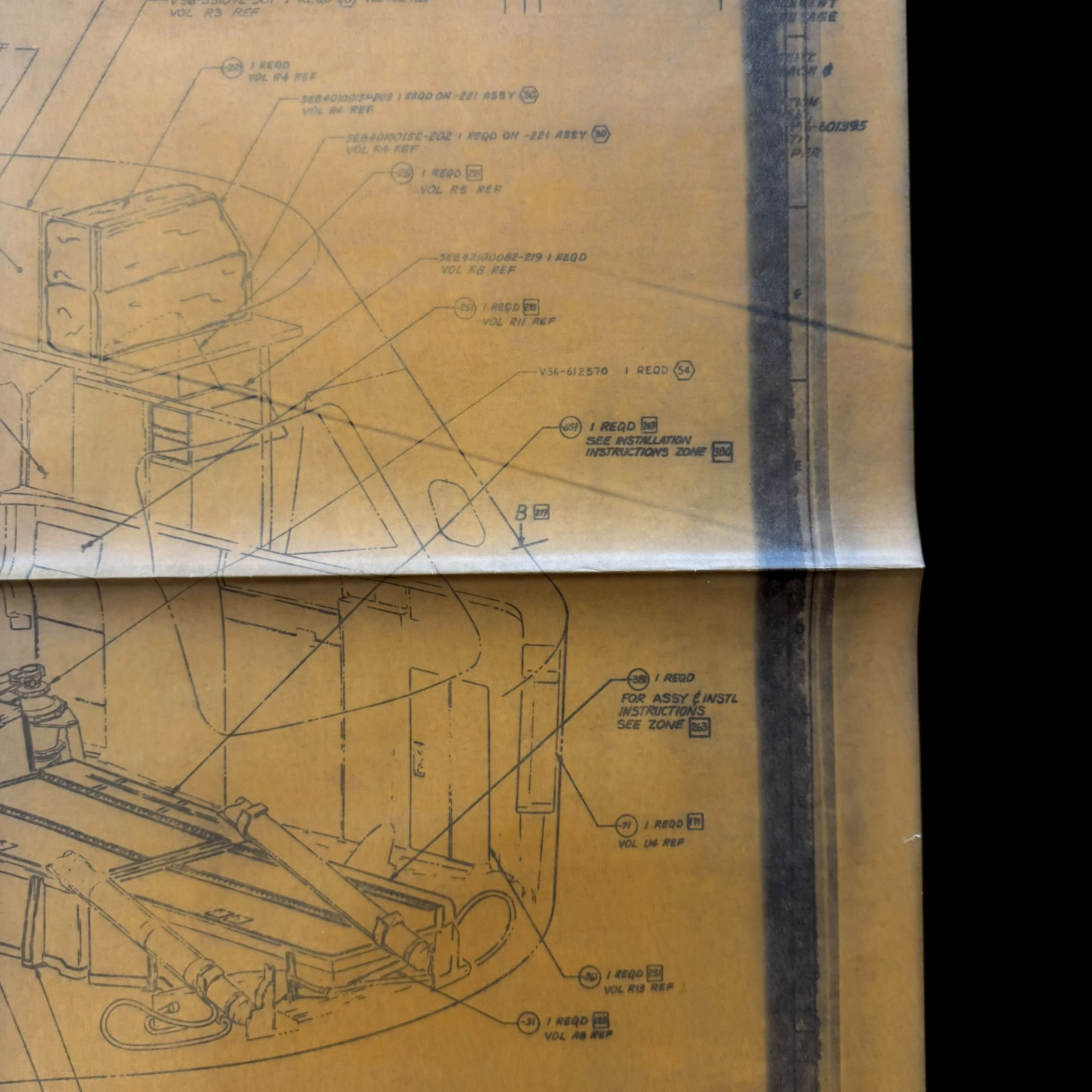

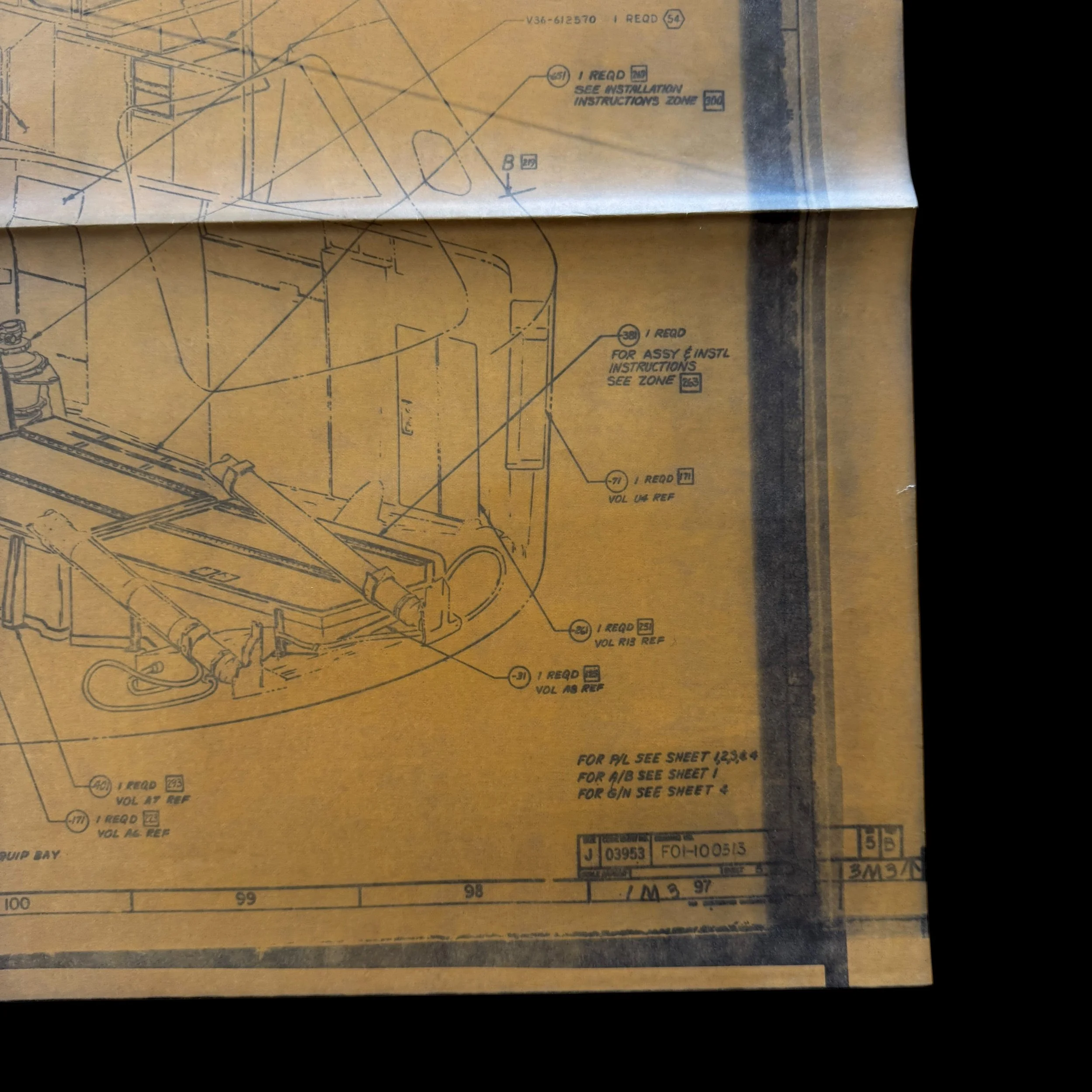

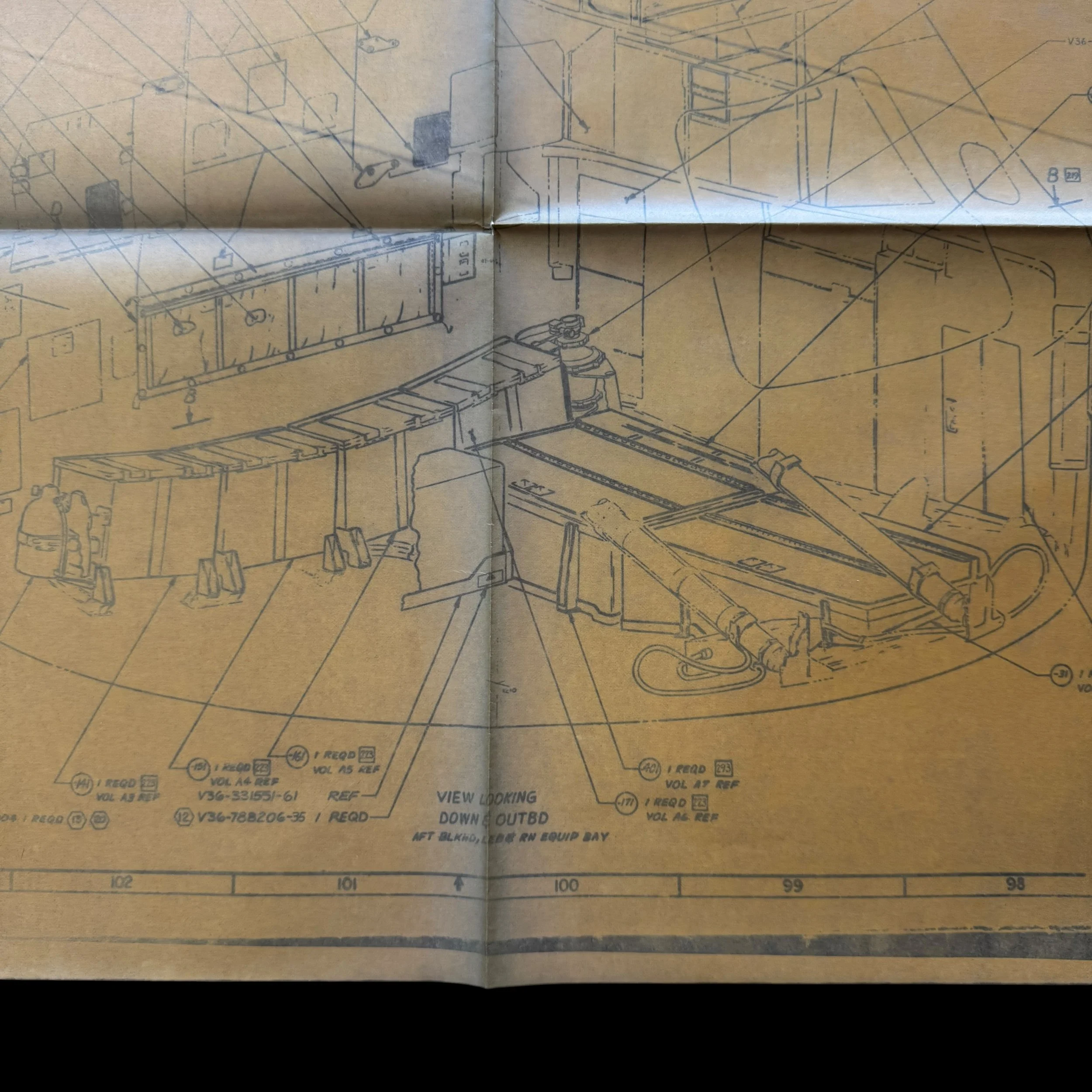

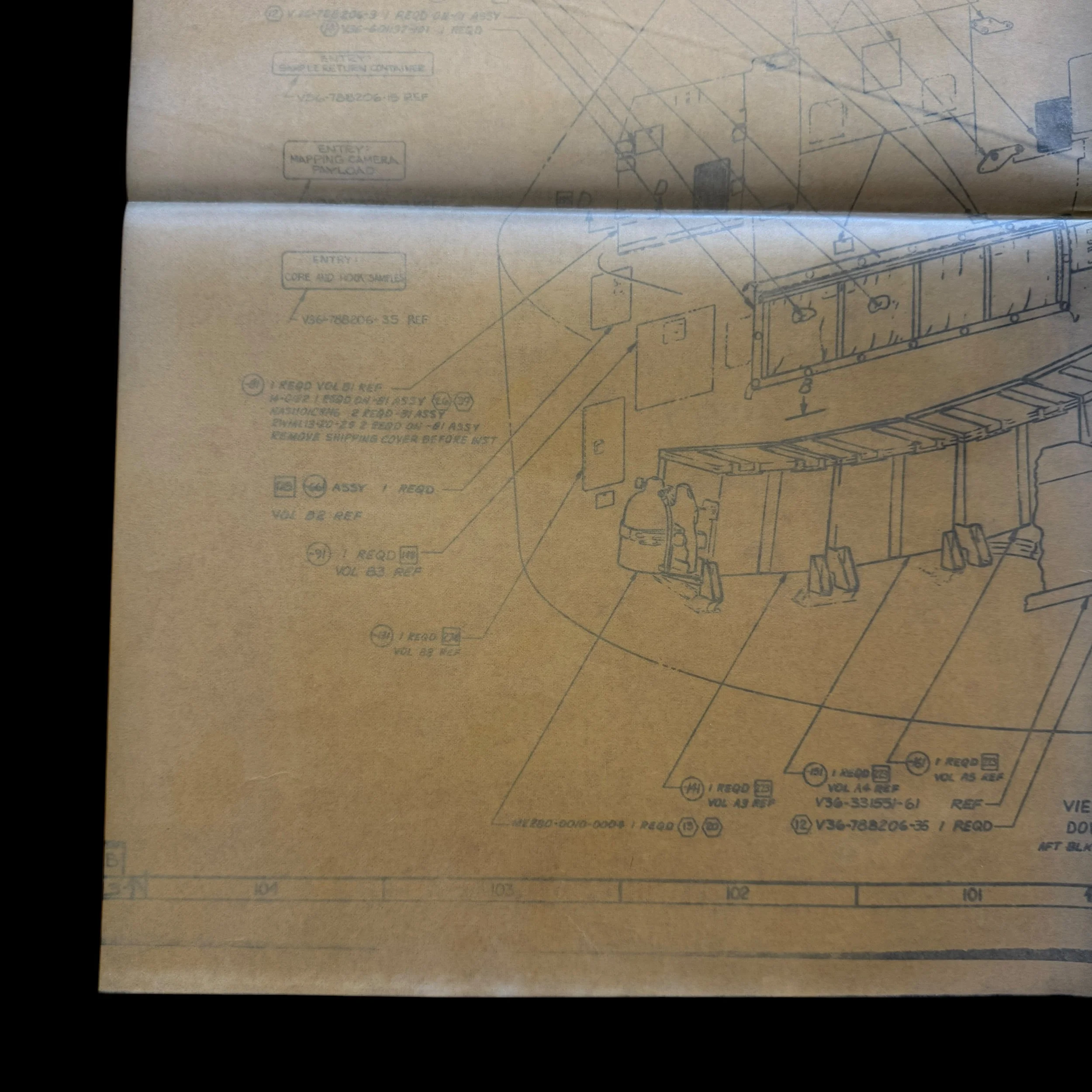

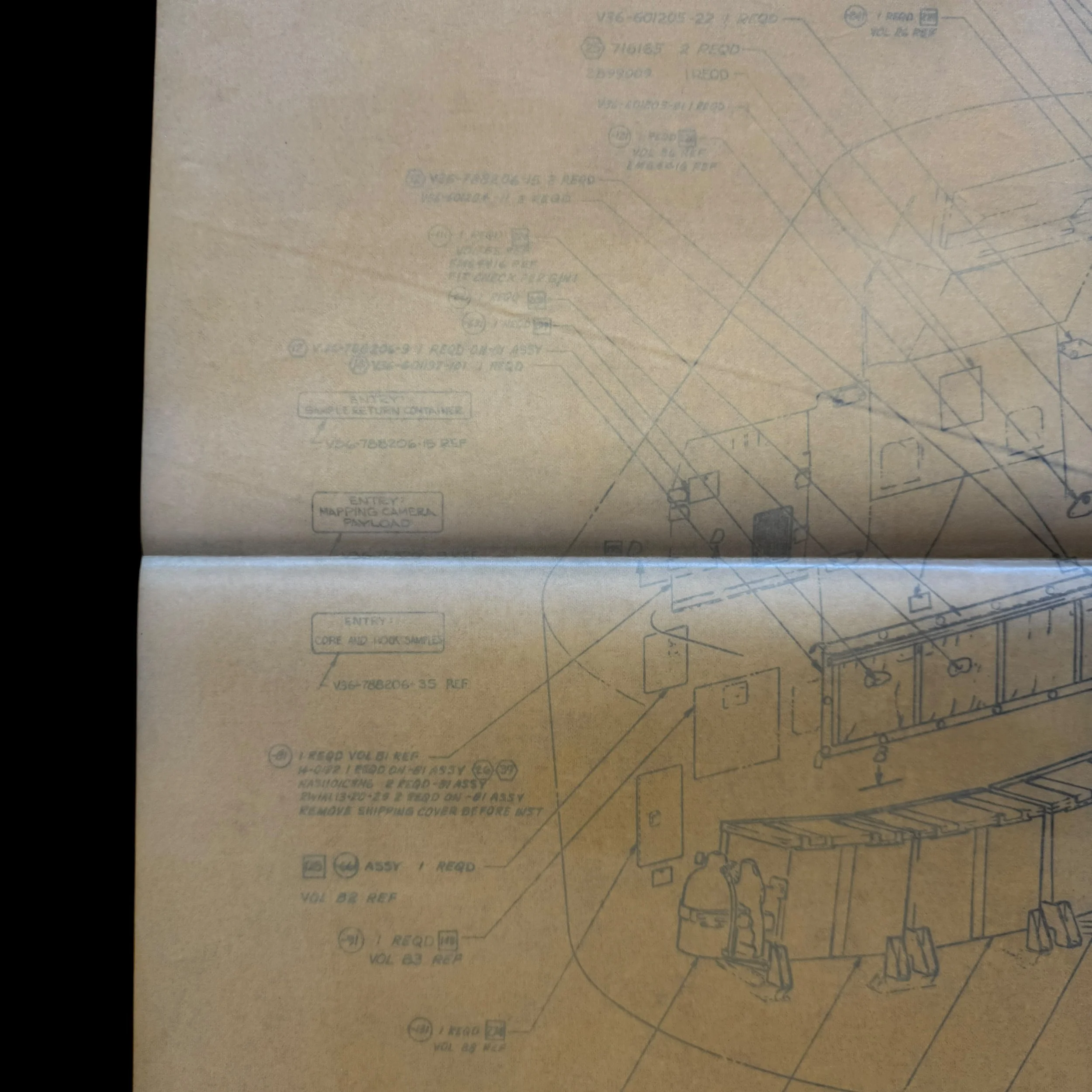

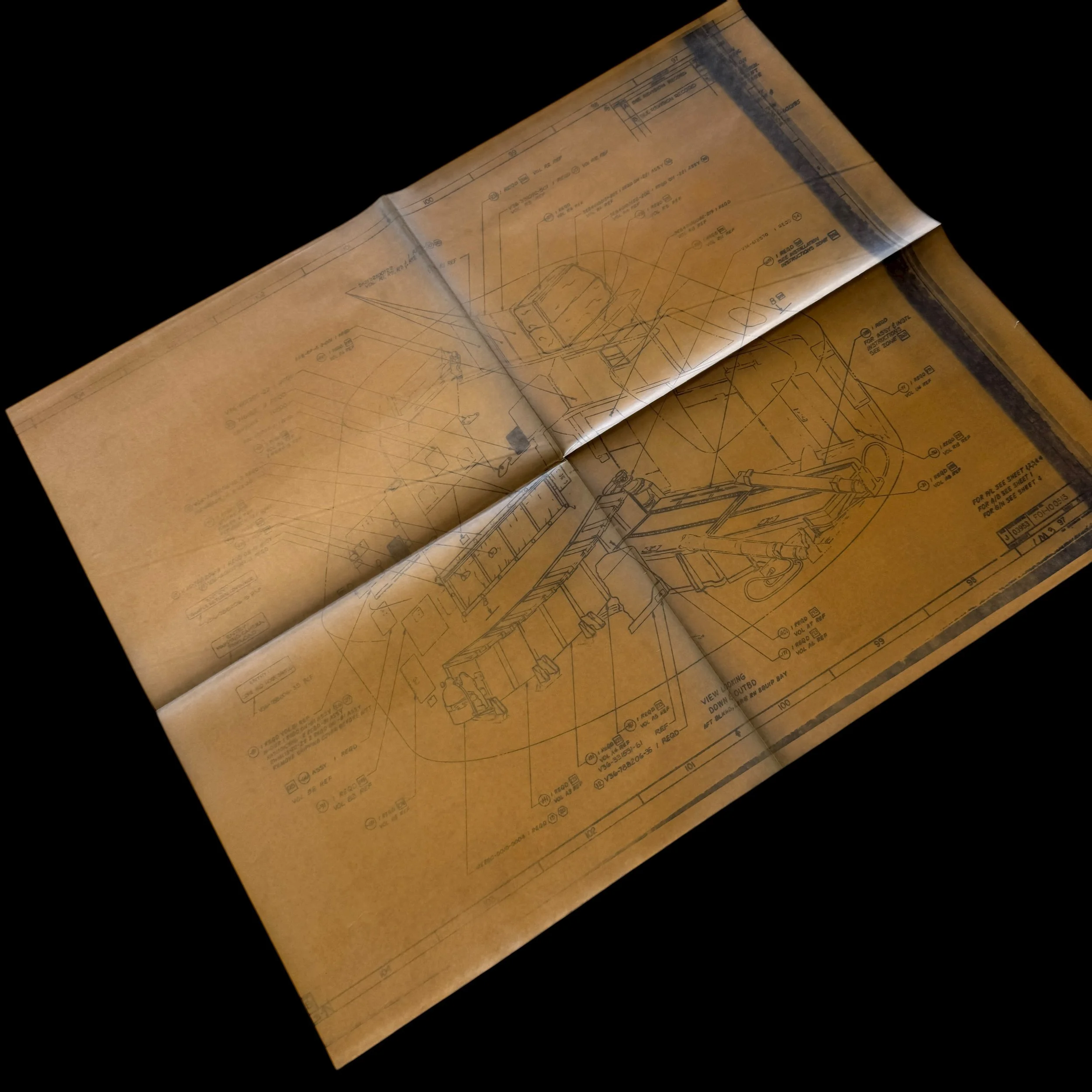

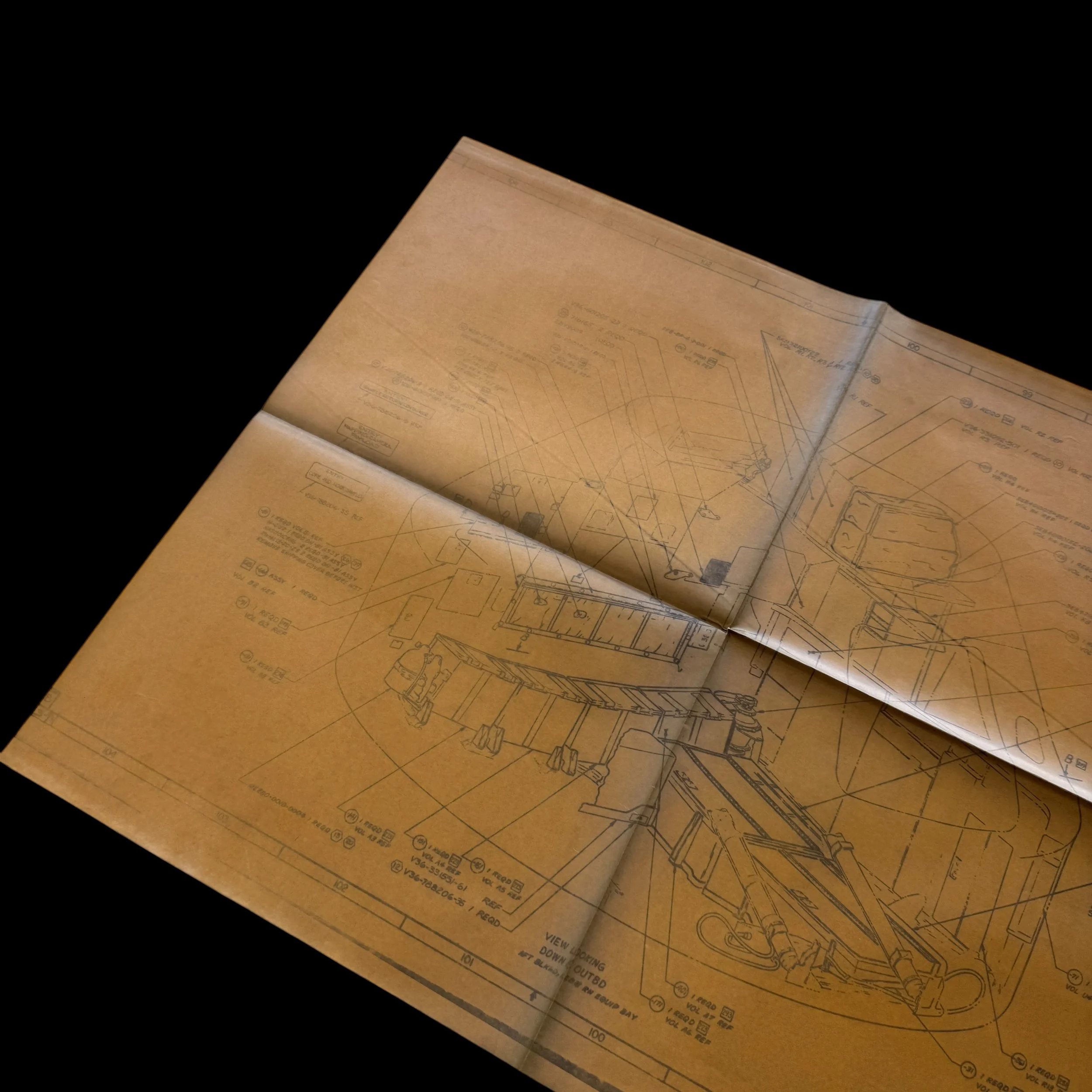

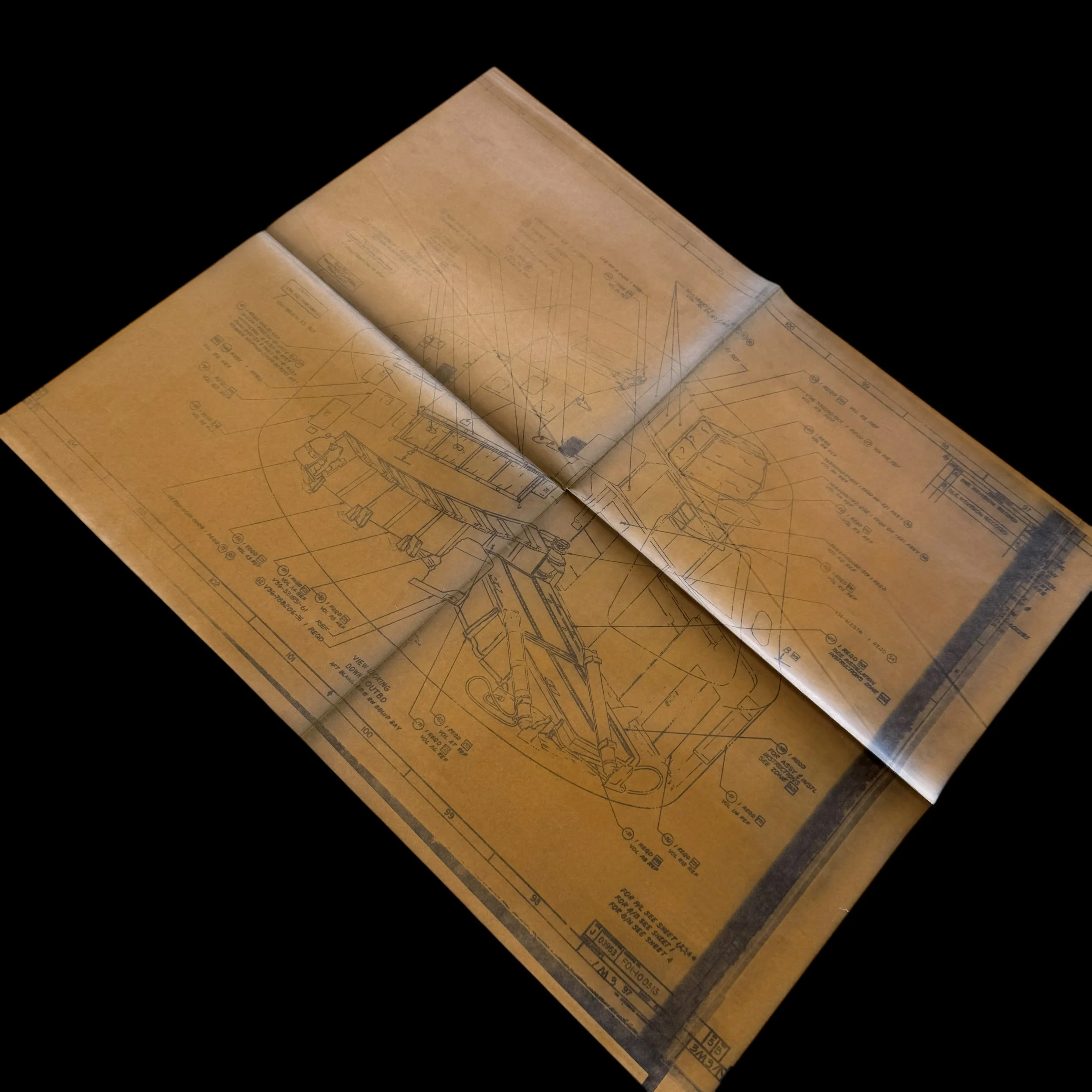

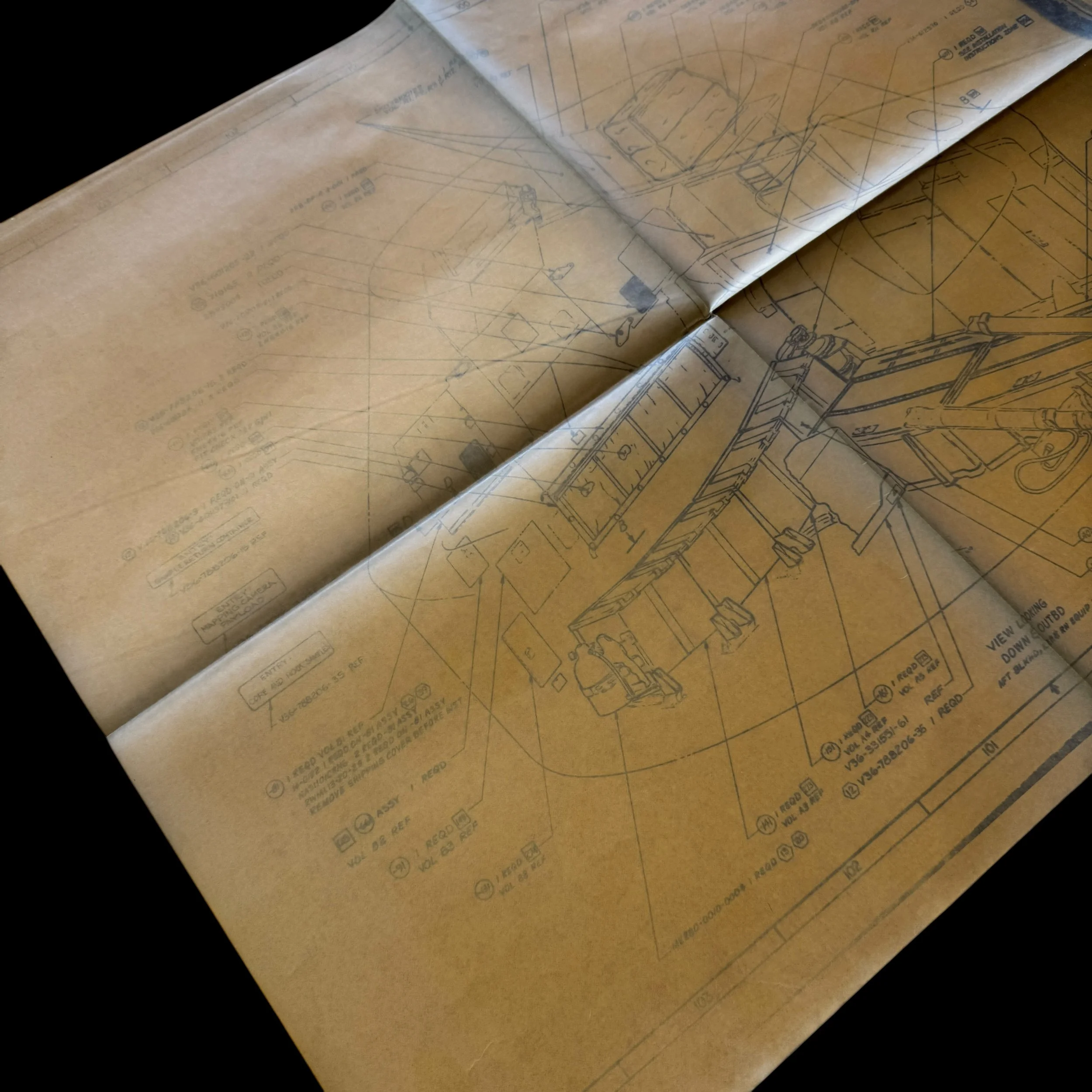

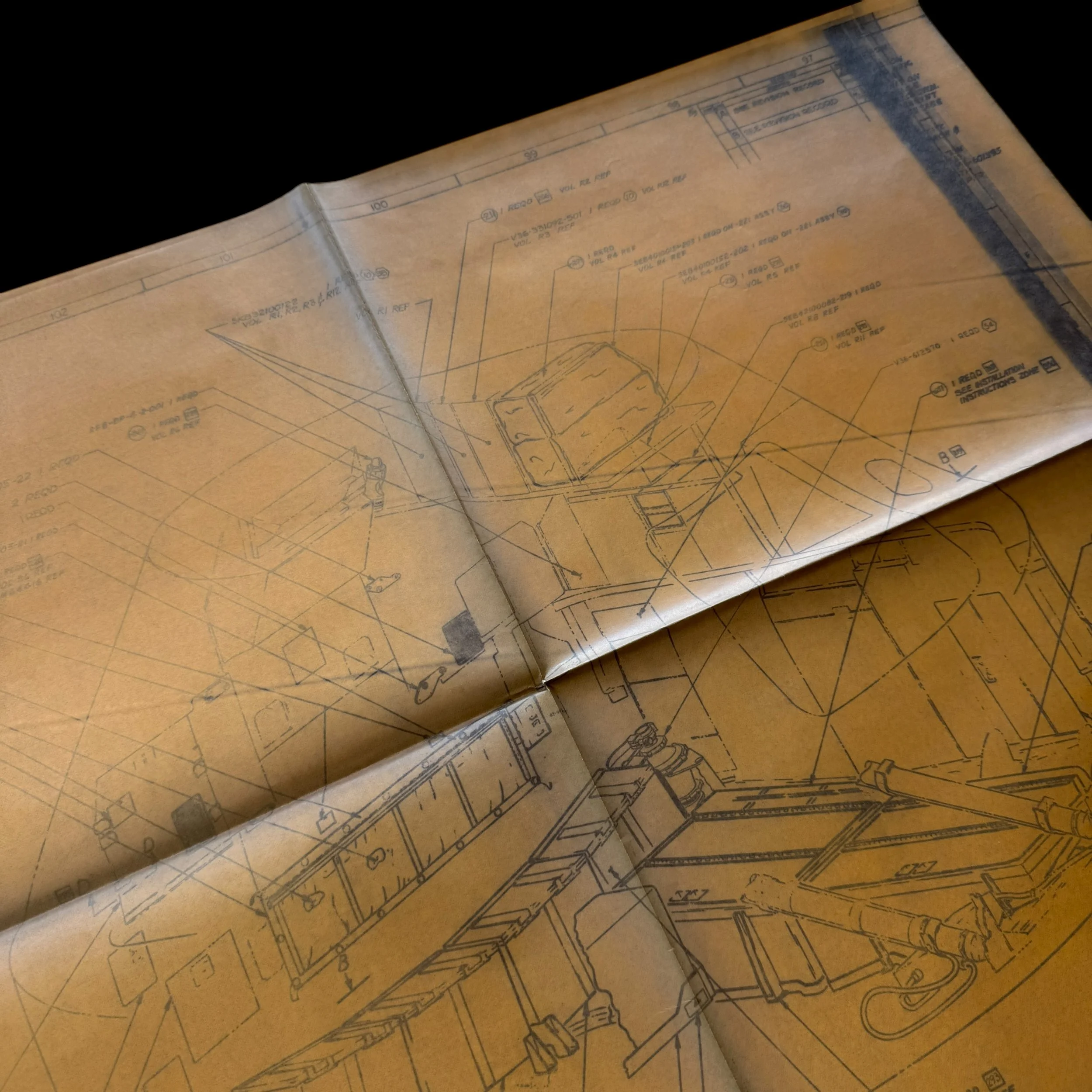

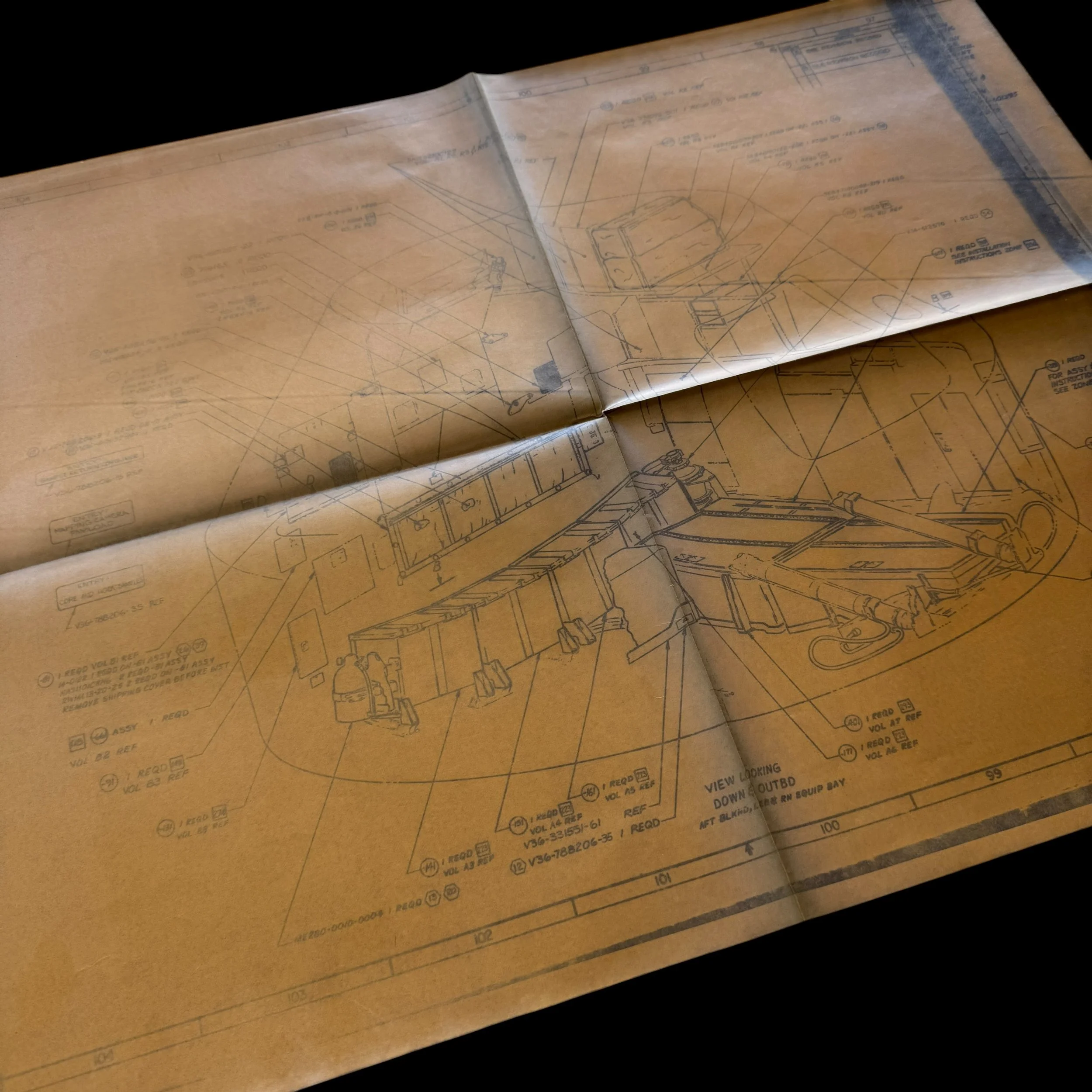

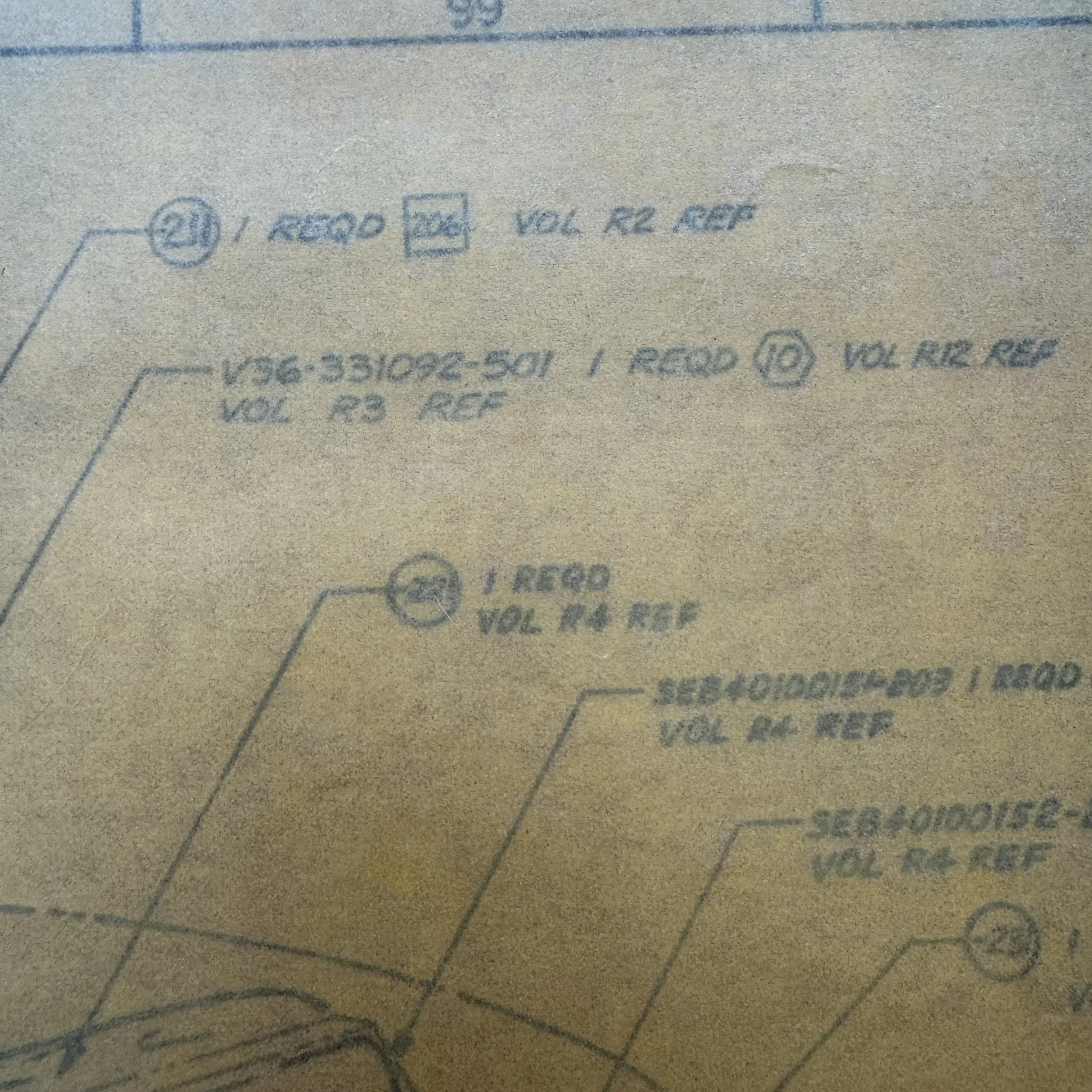

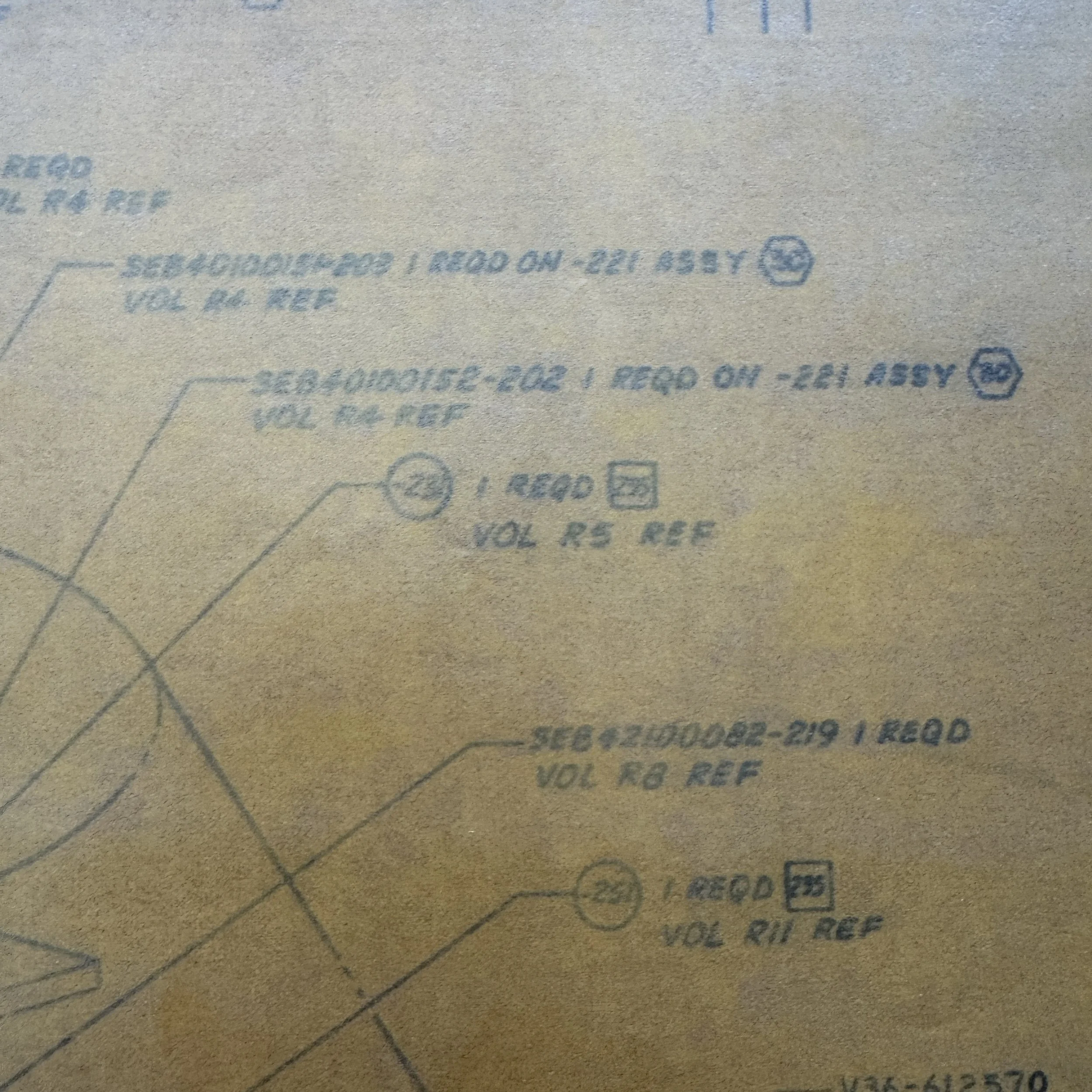

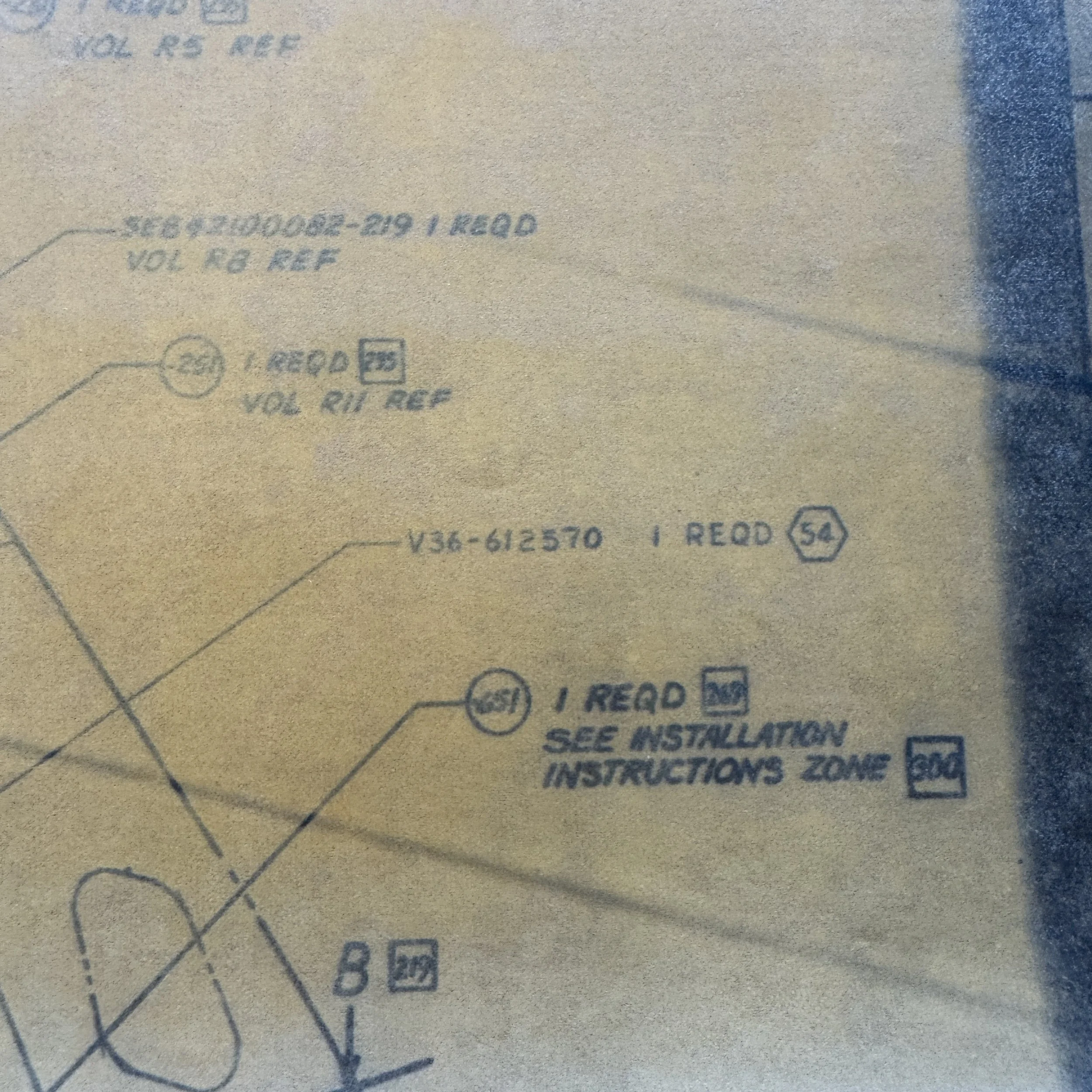

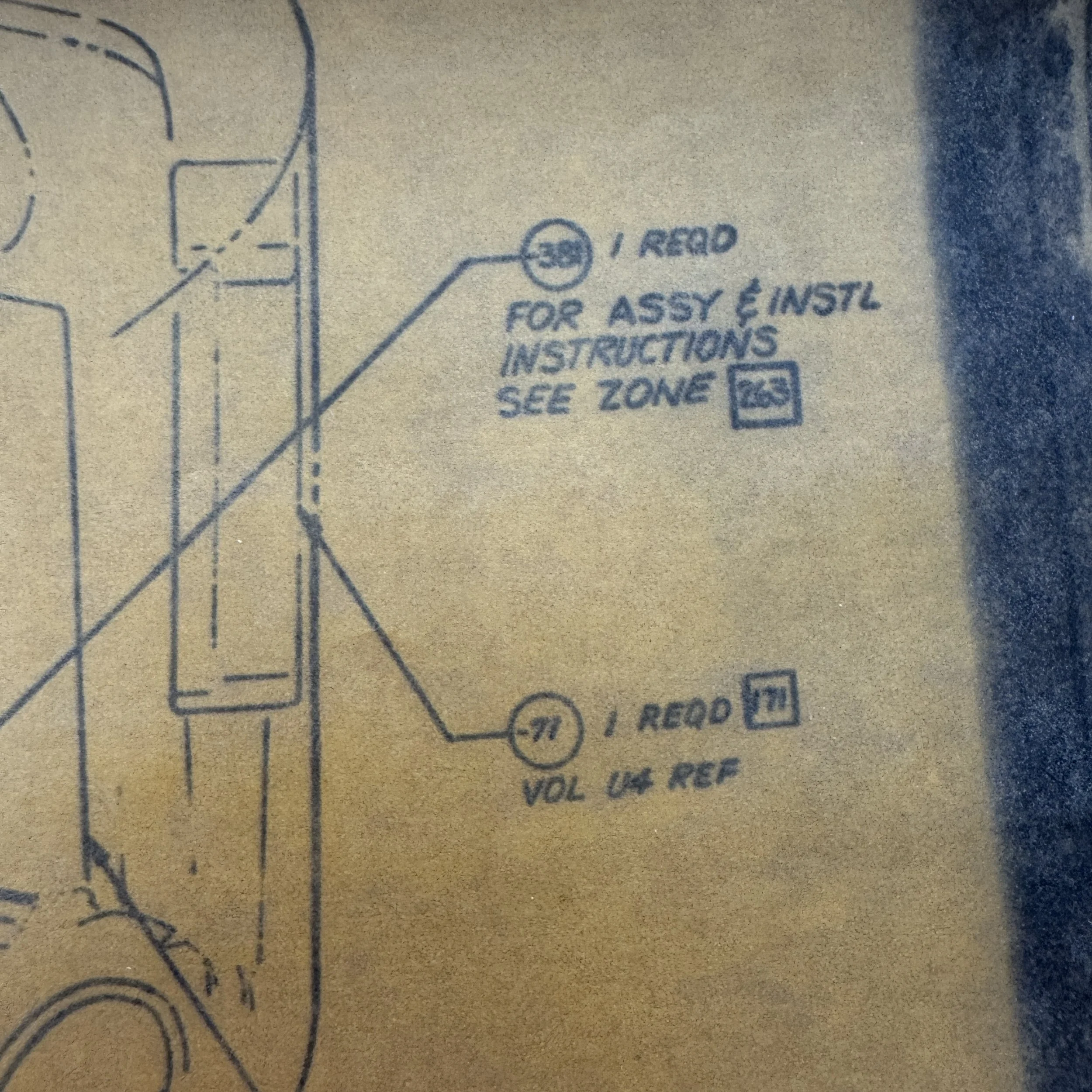

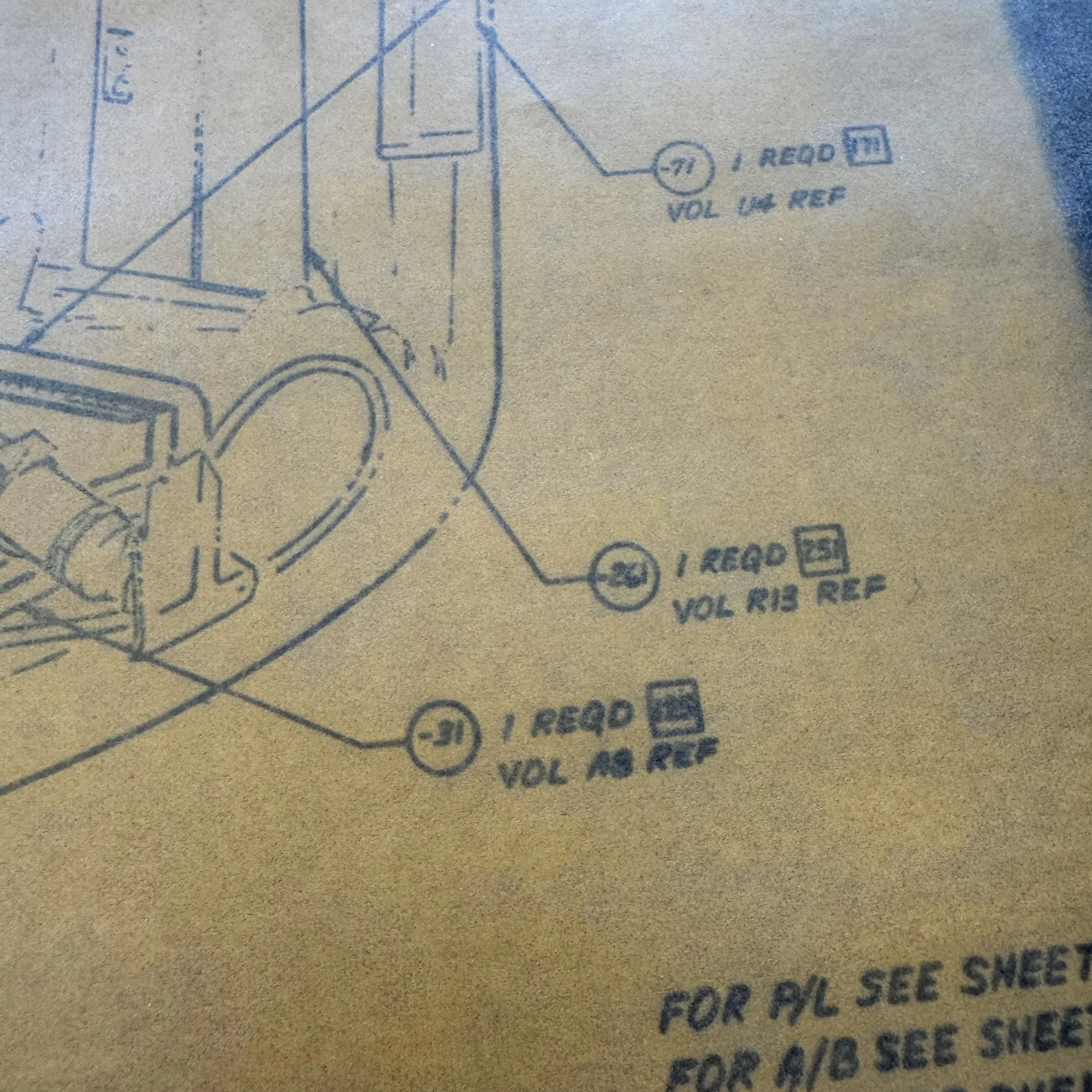

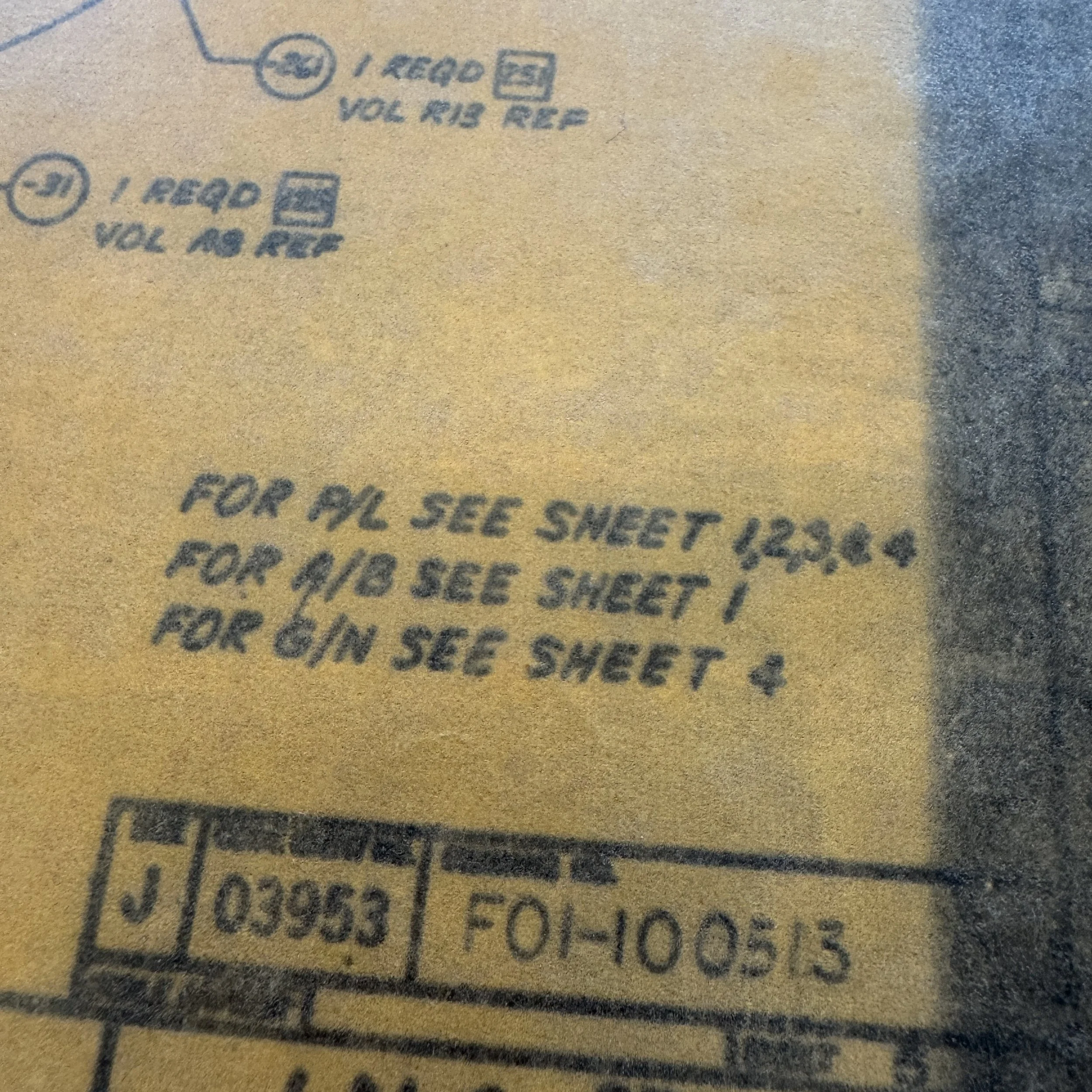

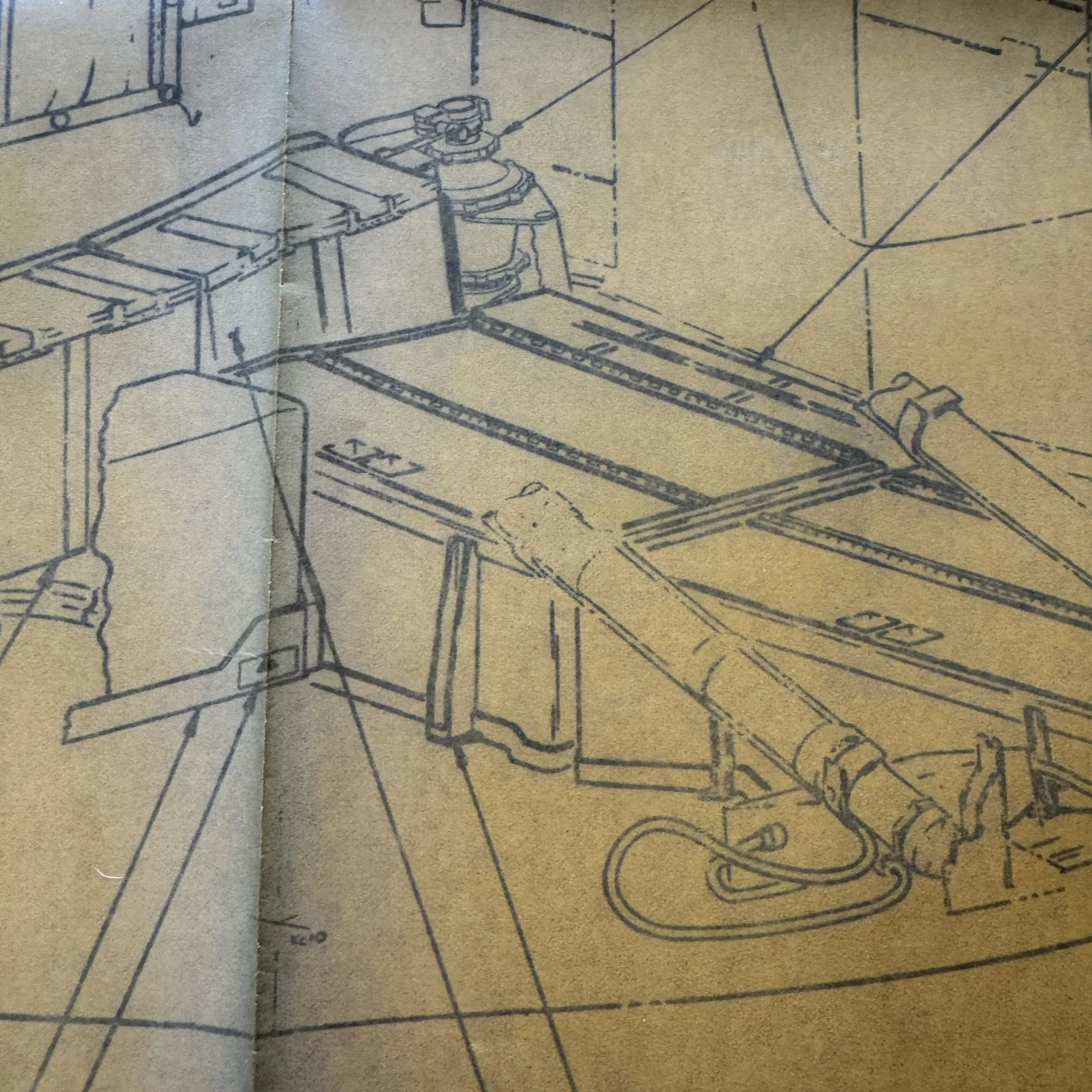

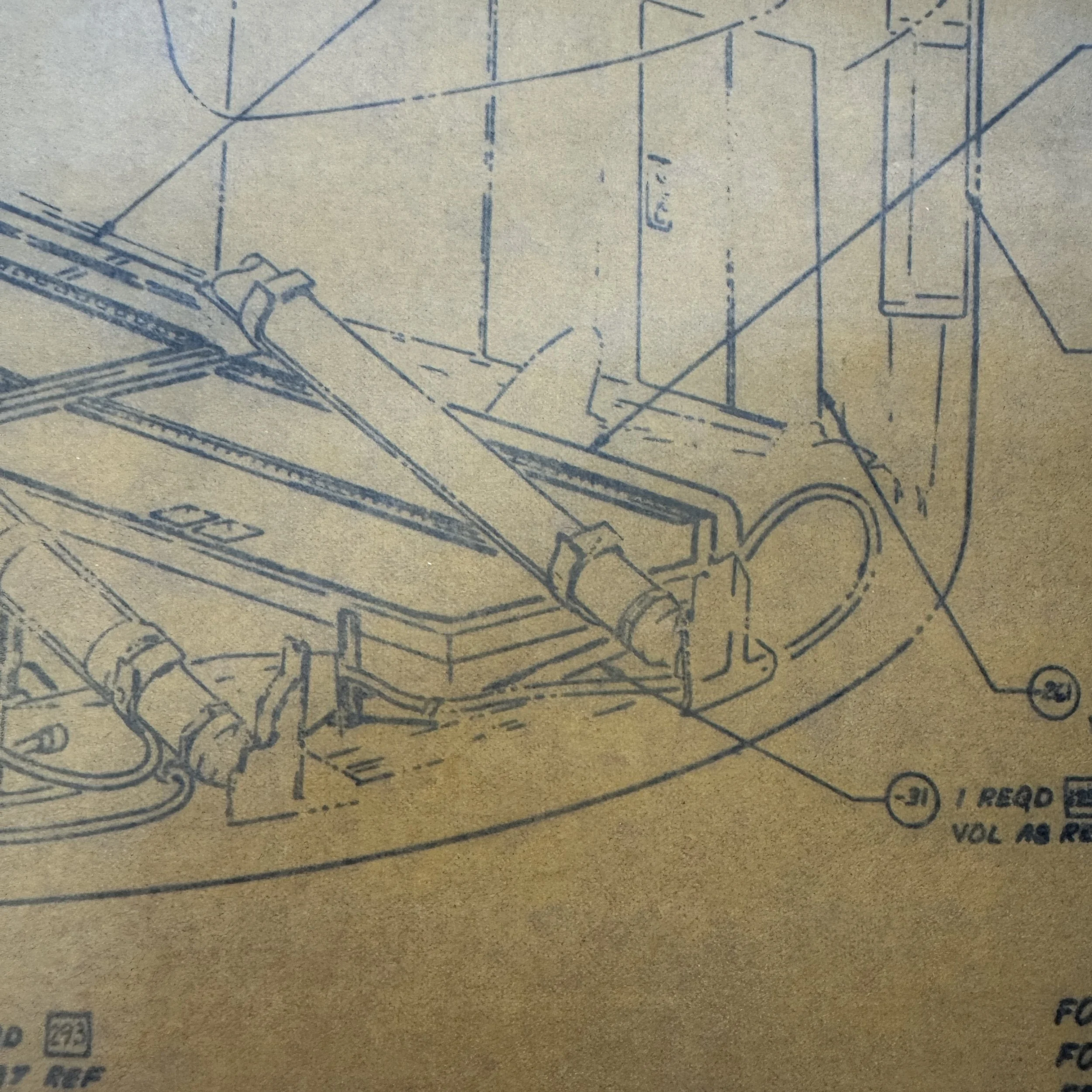

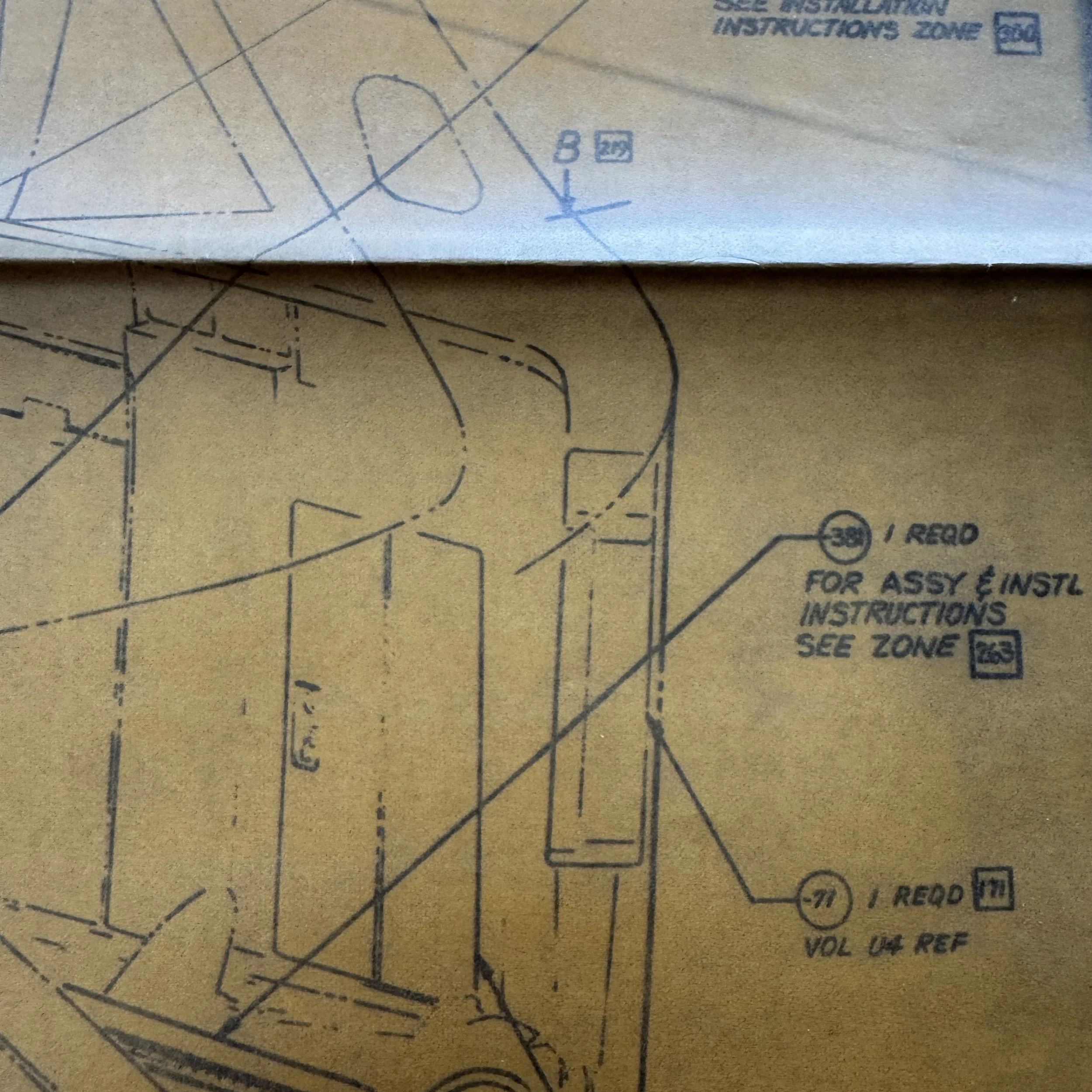

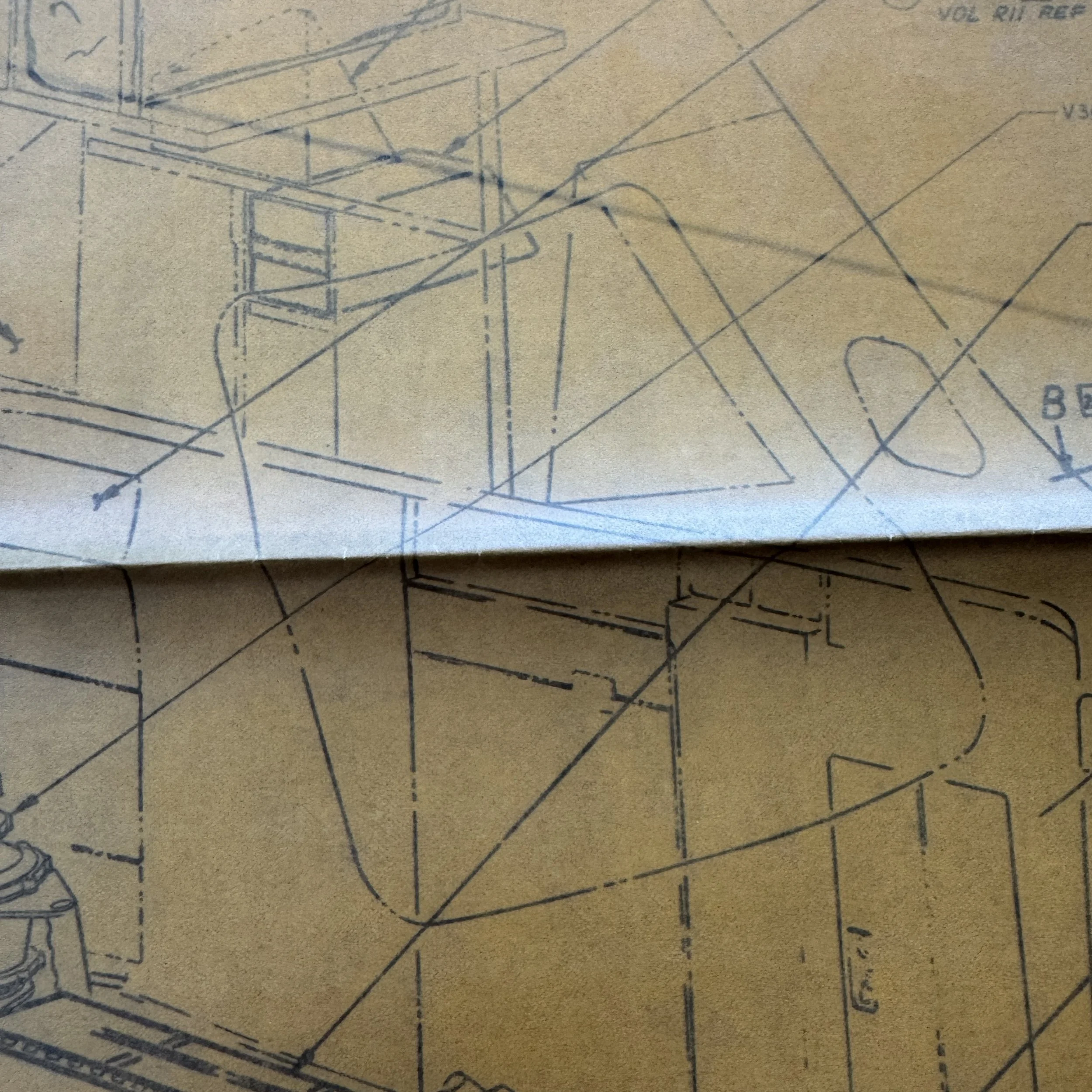

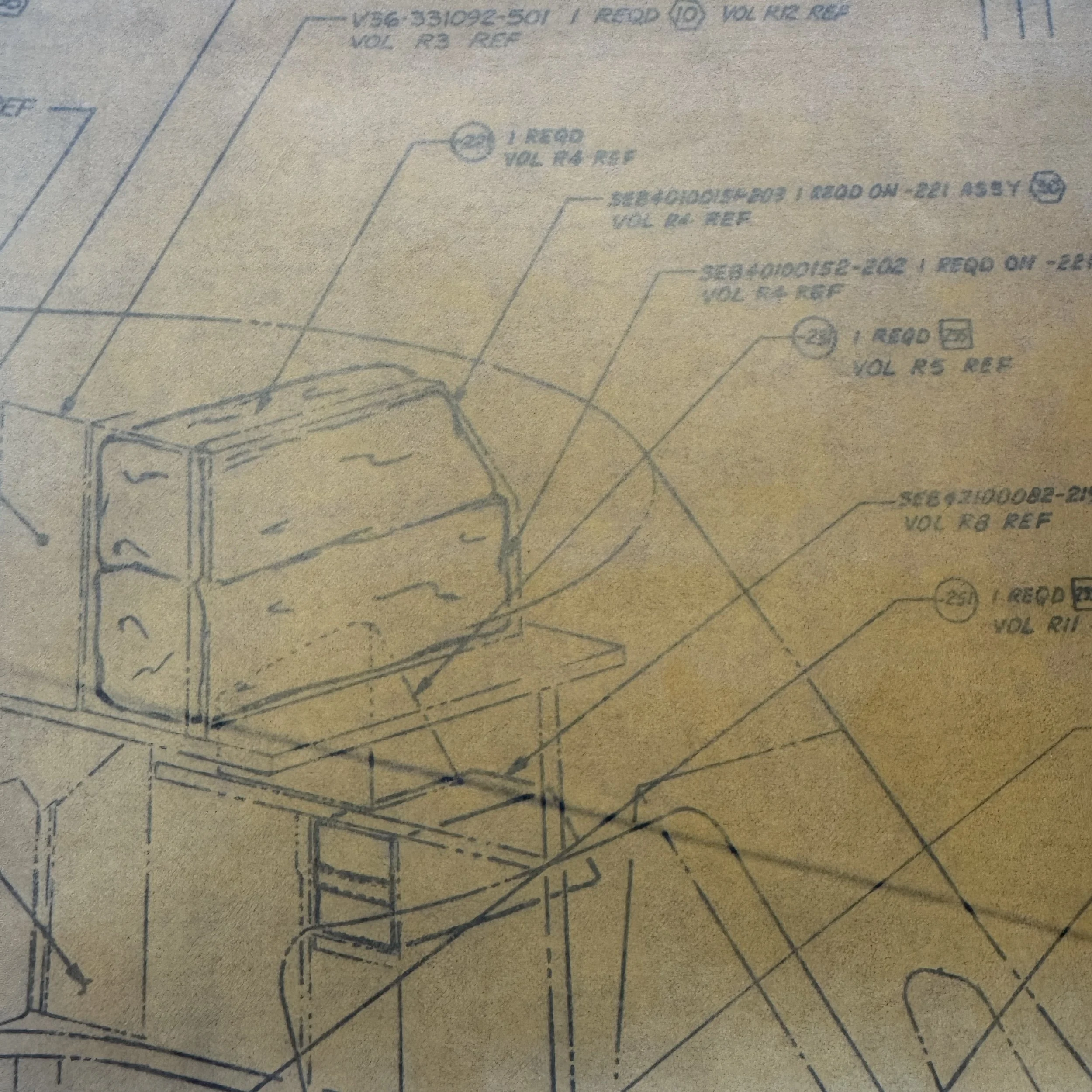

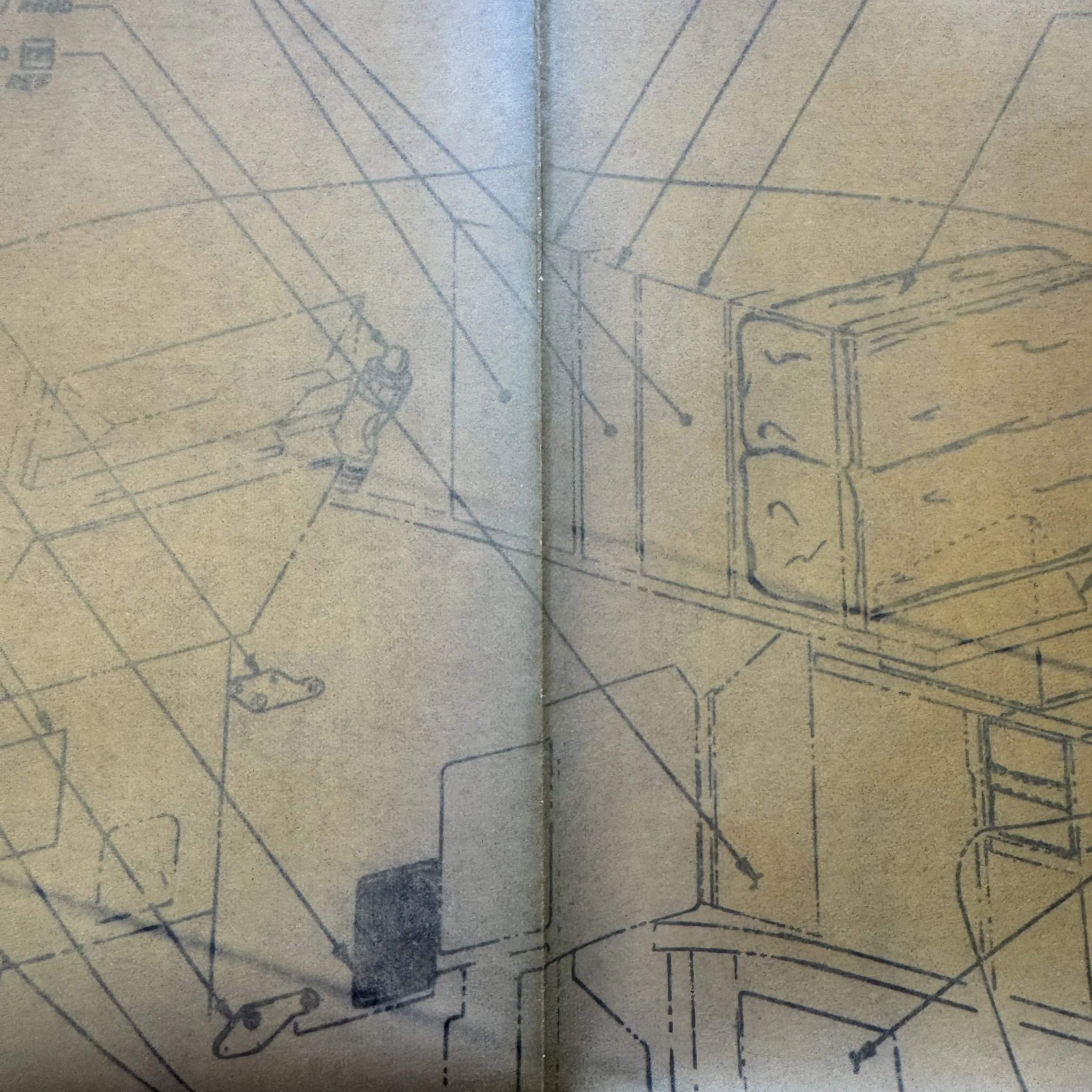

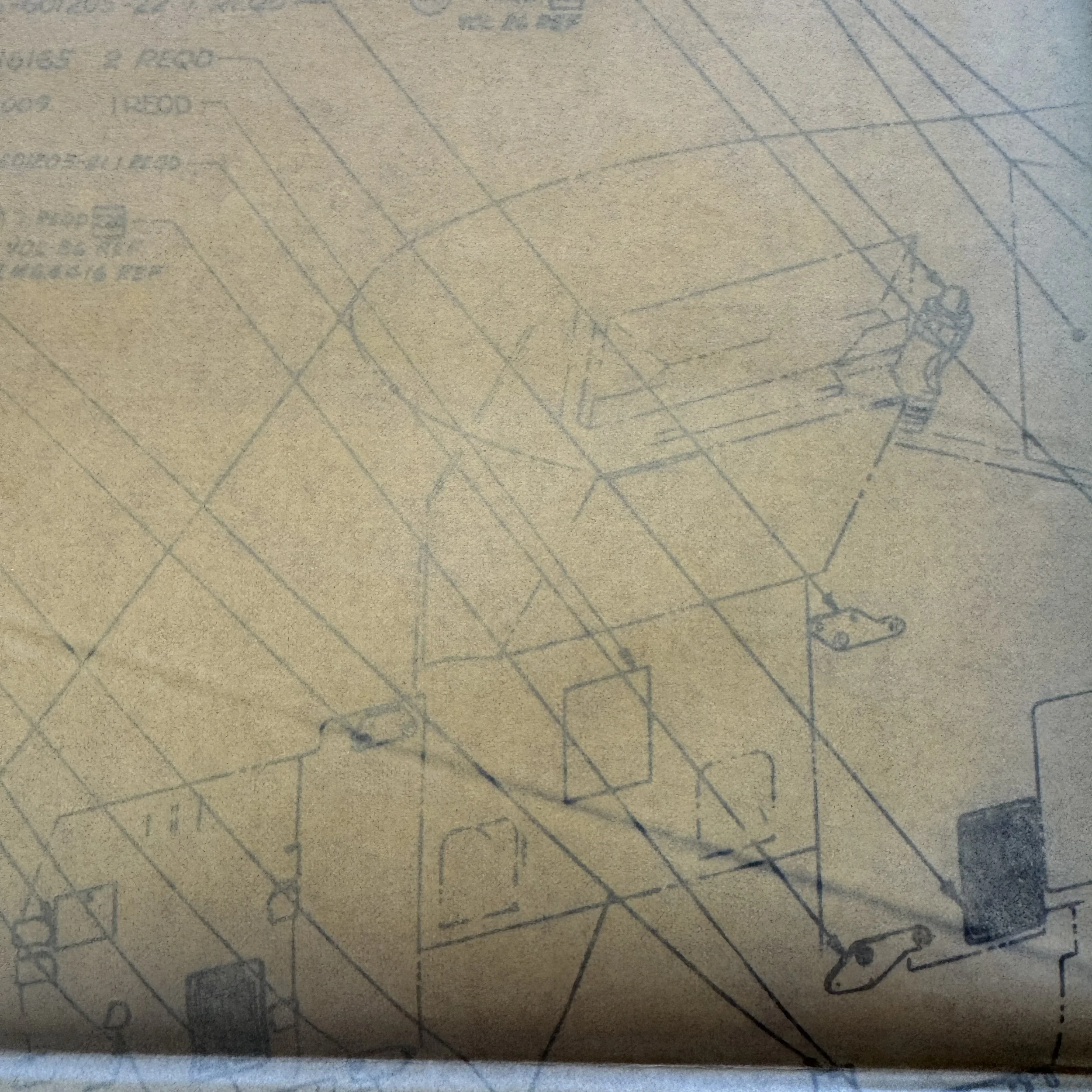

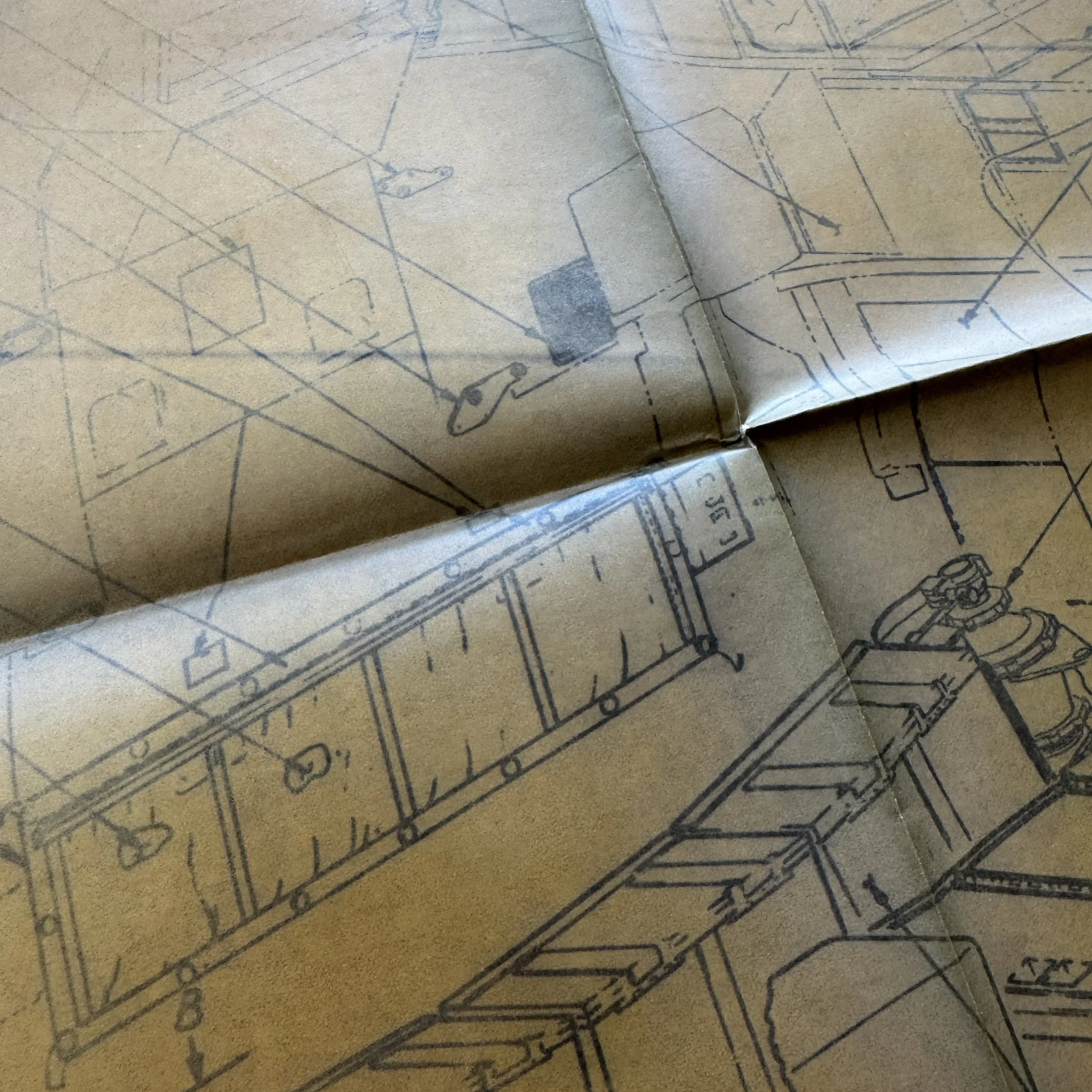

Type: Original NASA Apollo Program Command Service Module (CSM) Blueprint

Date: 1971 (preparation period for Apollo 16 & Apollo 17 missions)

Size: 18×23 inches

Use: Working engineering document used by NASA engineers and contractors for design modifications and mission improvements to the Apollo CSM

Program Significance: Directly tied to the 10th crewed Apollo mission and 5th lunar landing (Apollo 16, April 1972)

Mission Relevance: Blueprint reflects changes from earlier Apollo flights, including upgraded power distribution, enhanced redundancy after Apollo 13, environmental control refinements, and adaptations for extended lunar surface stays with the Lunar Rover

Associated Missions: Apollo 16 (“Casper” CSM, crewed by John Young, Charles Duke, Ken Mattingly) and Apollo 17, the final Apollo lunar landing

Condition: Museum-grade, authentic NASA artifact with clear technical linework and original 1971 date

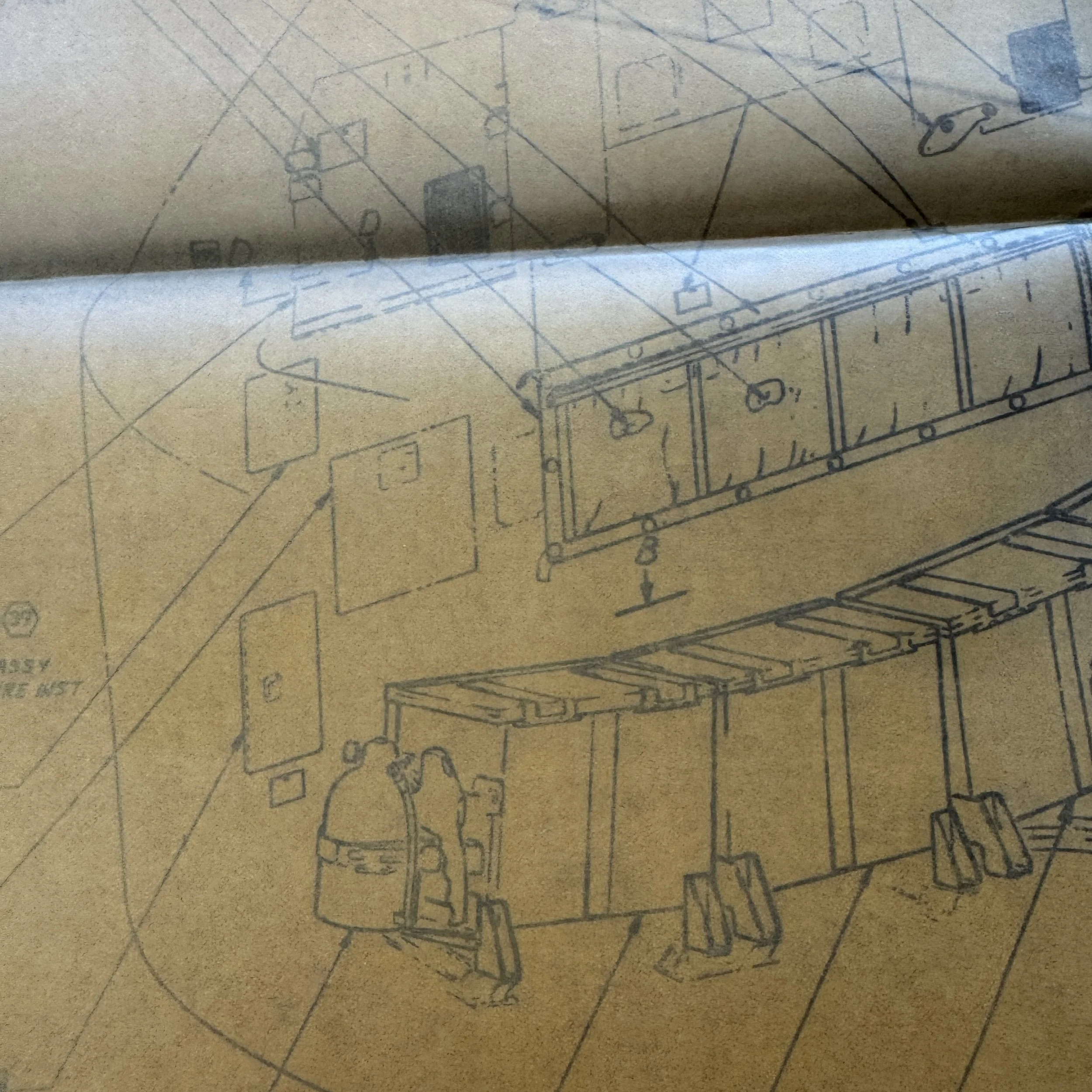

This museum-grade original NASA Apollo Program artifact is an original Apollo Command Service Module (CSM) blueprint dated 1971 and was used by NASA engineers for changes and modifications for the upcoming 10th crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program and the 5th lunar landing of the Apollo Program.

Apollo 16, flown from April 16–27, 1972, was the tenth crewed mission, and the second of Apollo’s advanced “J missions.” These flights marked a new phase in lunar exploration. They were longer, more ambitious, and designed with science at the forefront. This Apollo Program CSM blueprint represents one of the very NASA documents consulted daily by spacecraft engineers, systems specialists, and mission planners to implement the engineering improvements that made Apollo 16 not only possible but historically significant.

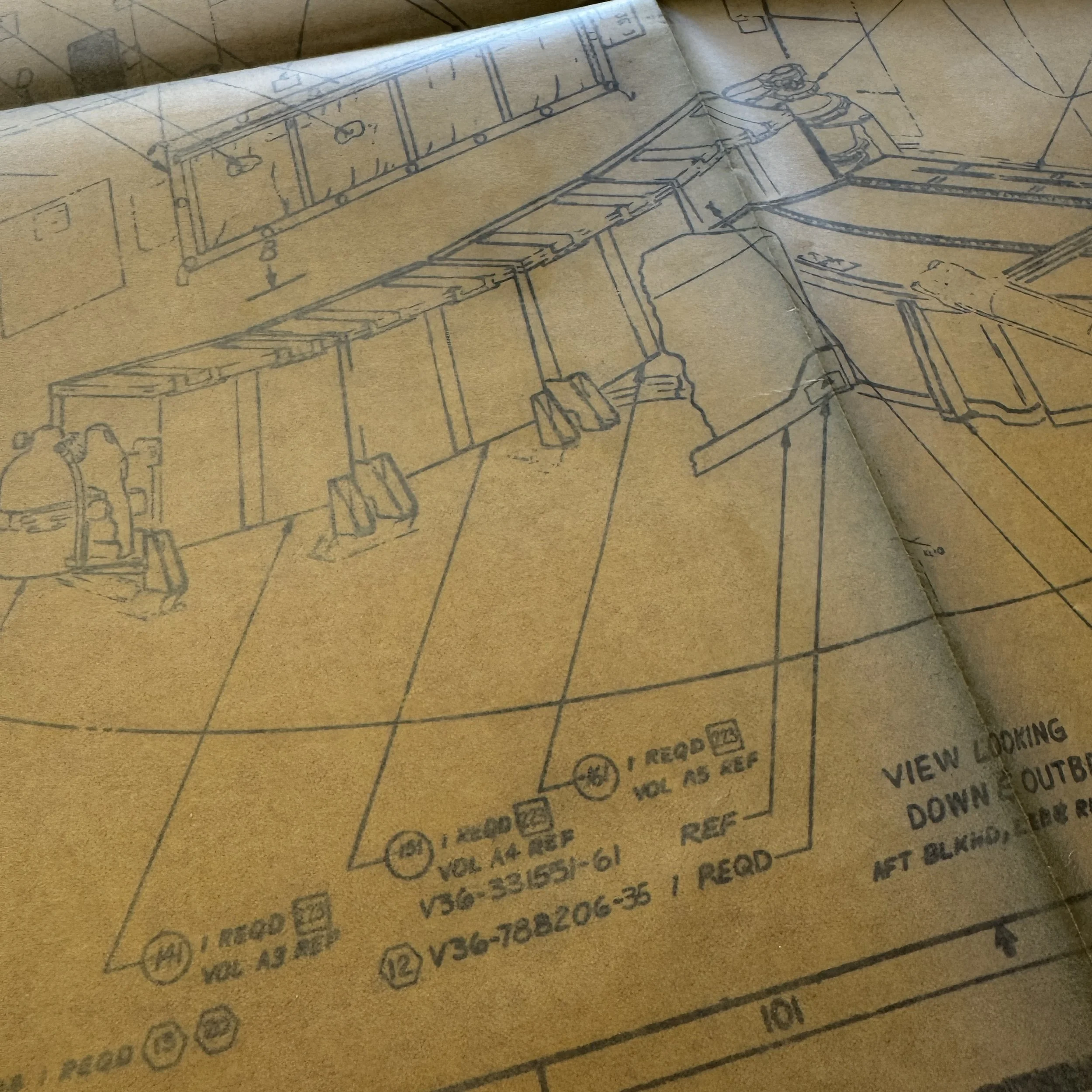

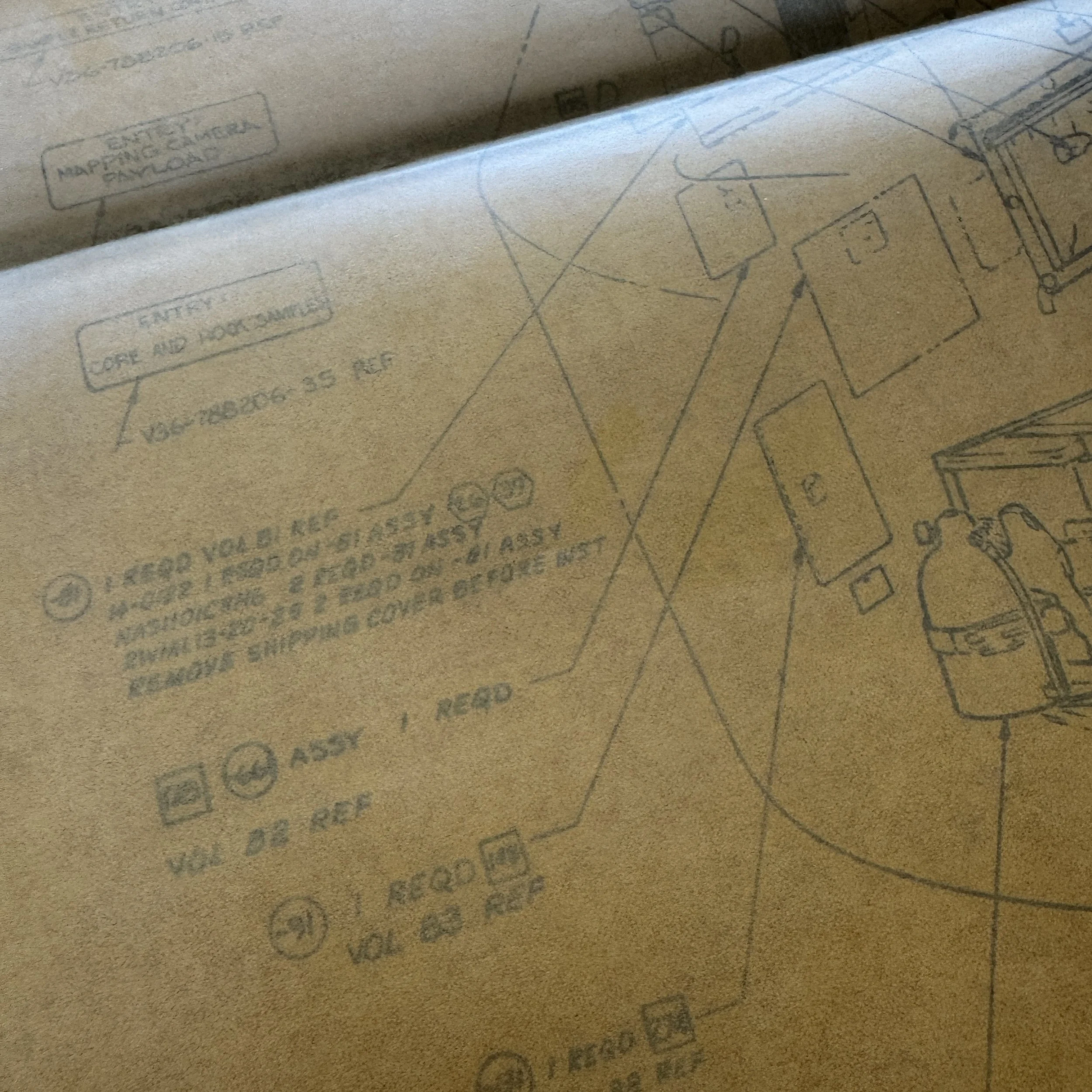

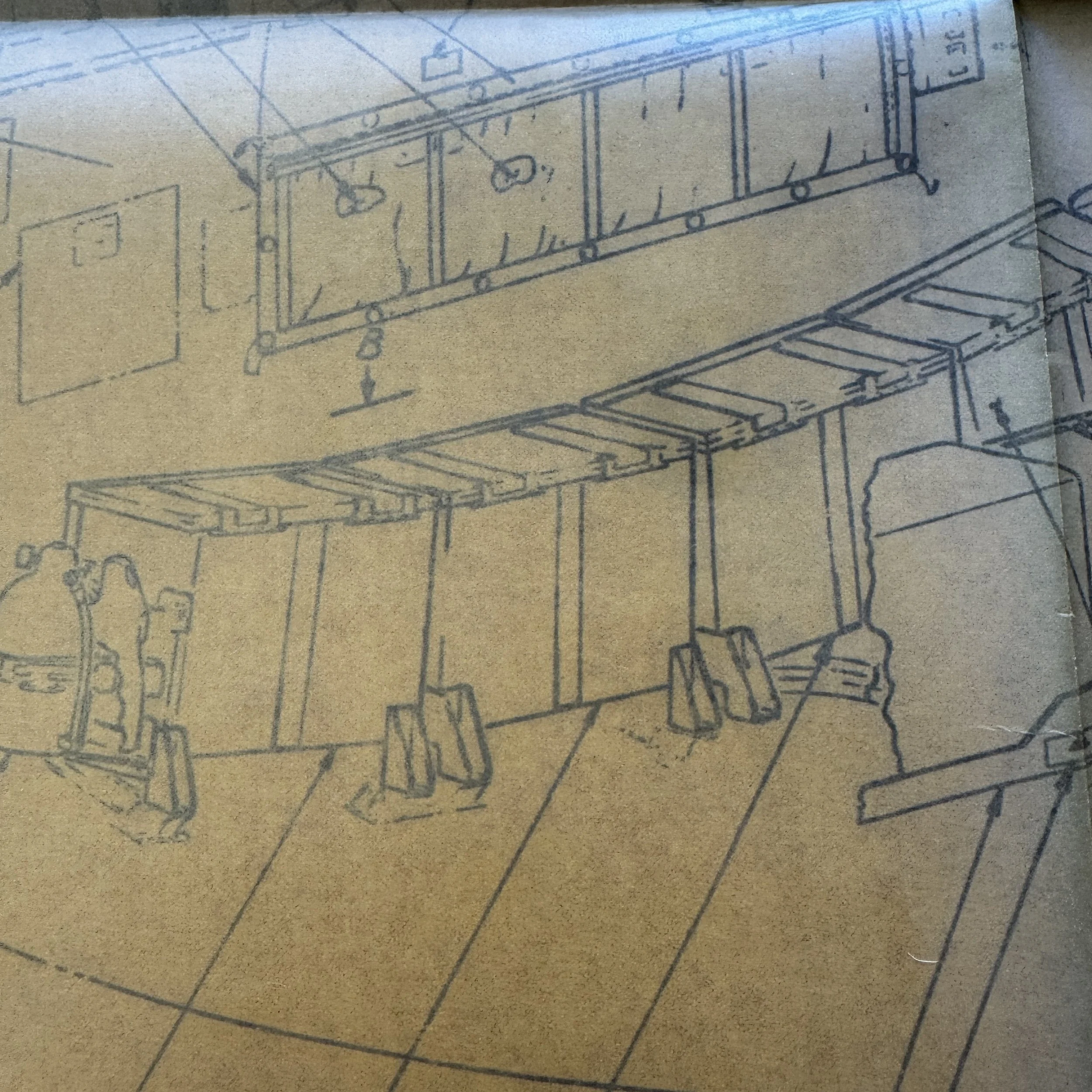

The Apollo Command and Service Module was the heart of the Apollo spacecraft system. It carried astronauts to the Moon, sustained them in orbit, and brought them safely home. By 1971, NASA engineers at North American Rockwell and flight planners at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston had already logged the successes—and the close calls—of earlier missions. These blueprints were used at drafting tables, design review boards, and integration meetings to chart out critical changes. Apollo 13’s near disaster made it clear that redundancy and power management were not optional. Engineers worked directly from blueprint sets like this one to reroute electrical systems, improve fault tolerance, and harden environmental controls. Apollo 15, the first of the J missions, introduced the Lunar Rover, but engineers quickly saw how its addition strained communications and power loads. The 1971 CSM updates reflected solutions to these problems, ensuring that Apollo 16 could push farther without compromising safety.

For Apollo 16, the astronauts—Commander John Young, Lunar Module Pilot Charles Duke, and Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly—depended on these blueprint-driven refinements. The command module “Casper” received upgraded guidance systems for better precision in lunar orbit, improved oxygen and cooling systems for reliability, and redesigned power distribution that allowed Mattingly to conduct orbital experiments while supporting Young and Duke’s extended stay on the lunar surface. The Descartes Highlands, their landing site, had been chosen because many believed it was volcanic in origin. Thanks to the mission, it was revealed instead to be shaped by ancient impacts, rewriting scientific understanding of the Moon.

These upgrades were drawn, revised, and signed into reality on blueprints like this. Engineers used them to test load paths, calculate thermal tolerances, and lay out wiring modifications. Technicians at Kennedy Space Center worked from them while installing new components. Flight controllers studied them to anticipate potential failure points. In short, the blueprint was the working foundation that linked design rooms, assembly floors, and mission control consoles.

The legacy carried beyond Apollo 16. The same series of modifications informed Apollo 17, the final Apollo lunar landing, flown in December 1972. These improvements allowed Gene Cernan, Harrison Schmitt, and Ron Evans to carry out the most scientifically intensive lunar exploration in history. In this sense, the 1971 blueprint ties directly to both penultimate and final steps of humanity’s greatest venture to the Moon.

In many ways, Apollo 16 was the pinnacle of lunar science missions. The blueprint that contributed to its success is not simply a piece of paper. It is a physical link to the engineers who debated and refined every line, to the astronauts who trusted those changes with their lives, and to the broader story of how Apollo evolved from daring first steps to world-changing science.

Pre-Launch and Launch (April 16, 1972)

CSM Designation: CSM-113, nicknamed Casper by the crew.

Role: Provided life support, propulsion, navigation, and served as the command station during Earth orbit and lunar transit.

Liftoff: April 16, 1972, at 12:54 p.m. EST from Kennedy Space Center, LC-39A.

After separation from the Saturn V’s third stage (S-IVB), the CSM performed Transposition and Docking, extracting the Lunar Module (LM Orion) from the S-IVB. This maneuver was essential to prepare for the lunar voyage.

Earth Orbit Phase

The CSM supported the crew in Earth Parking Orbit while systems were checked.

Guidance, navigation, and control (GNC) systems in the CSM ensured proper alignment for Translunar Injection (TLI).

TLI burn executed by the S-IVB, followed by separation. The CSM then became the sole command vehicle.

Translunar Coast (April 16–19, 1972)

The Service Propulsion System (SPS), the main engine of the CSM, was fired for midcourse corrections to refine the trajectory to the Moon.

The crew used CSM’s navigation optics to perform celestial sightings for alignment checks, ensuring precise navigation.

The CSM provided continuous life support, electrical power, and communication relay back to Earth.

Lunar Orbit Insertion (April 19, 1972)

Upon arrival, Casper performed a critical SPS burn to insert into lunar orbit.

Orbital parameters: approximately 60 nautical miles by 170 nautical miles.

Once stable in orbit, preparations began for the Lunar Module undocking.

Lunar Module Separation and CSM Operations (April 20–23, 1972)

On April 20, Orion undocked, carrying John Young and Charles Duke to the lunar surface.

Role of CSM in orbit:

Ken Mattingly, as Command Module Pilot, remained aboard Casper.

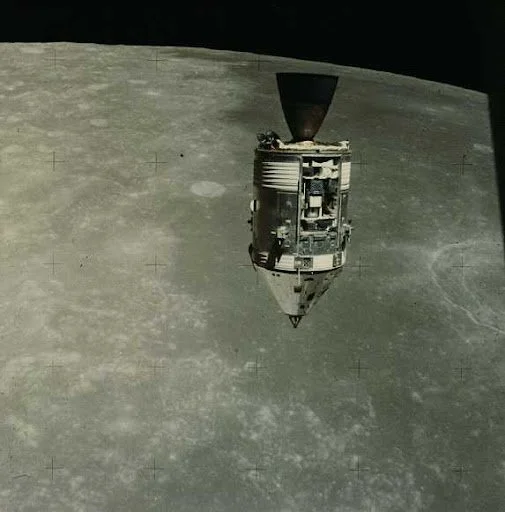

Conducted lunar orbital science with instruments mounted in the Service Module’s Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay.

Instruments included a gamma-ray spectrometer, mass spectrometer, X-ray spectrometer, and a panoramic camera.

Mattingly carried out orbital mapping, remote sensing, and photography to extend surface science beyond the landing site.

The CSM relayed communications between the LM and Mission Control in Houston.

Rendezvous and Docking (April 23, 1972)

After three days of surface exploration, Orion ascended from the lunar surface and rendezvoused with Casper.

CSM’s role: precise orbital maneuvers for rendezvous and docking.

The SPS engine performed burns to synchronize orbits.

Successful docking occurred, and lunar samples and equipment were transferred to Casper.

Trans-Earth Injection (April 24, 1972)

With the LM jettisoned, Casper remained the sole spacecraft for the return trip.

The SPS was fired in a long-duration burn to break free from lunar orbit and set course for Earth.

Transearth Coast (April 24–27, 1972)

The CSM supported life functions and provided midcourse corrections.

Mattingly conducted a deep-space EVA on April 25, retrieving film canisters from the SIM bay. This was the second deep-space EVA in history.

The EVA highlighted the importance of the CSM as a mobile science platform, not just a transport vehicle.

Reentry and Splashdown (April 27, 1972)

Near Earth, the Service Module was jettisoned, exposing the heat shield of the Command Module.

Casper’s Command Module reentered Earth’s atmosphere at nearly 25,000 mph.

Splashdown occurred on April 27, 1972, in the Pacific Ocean. The crew was recovered by the USS Ticonderoga.