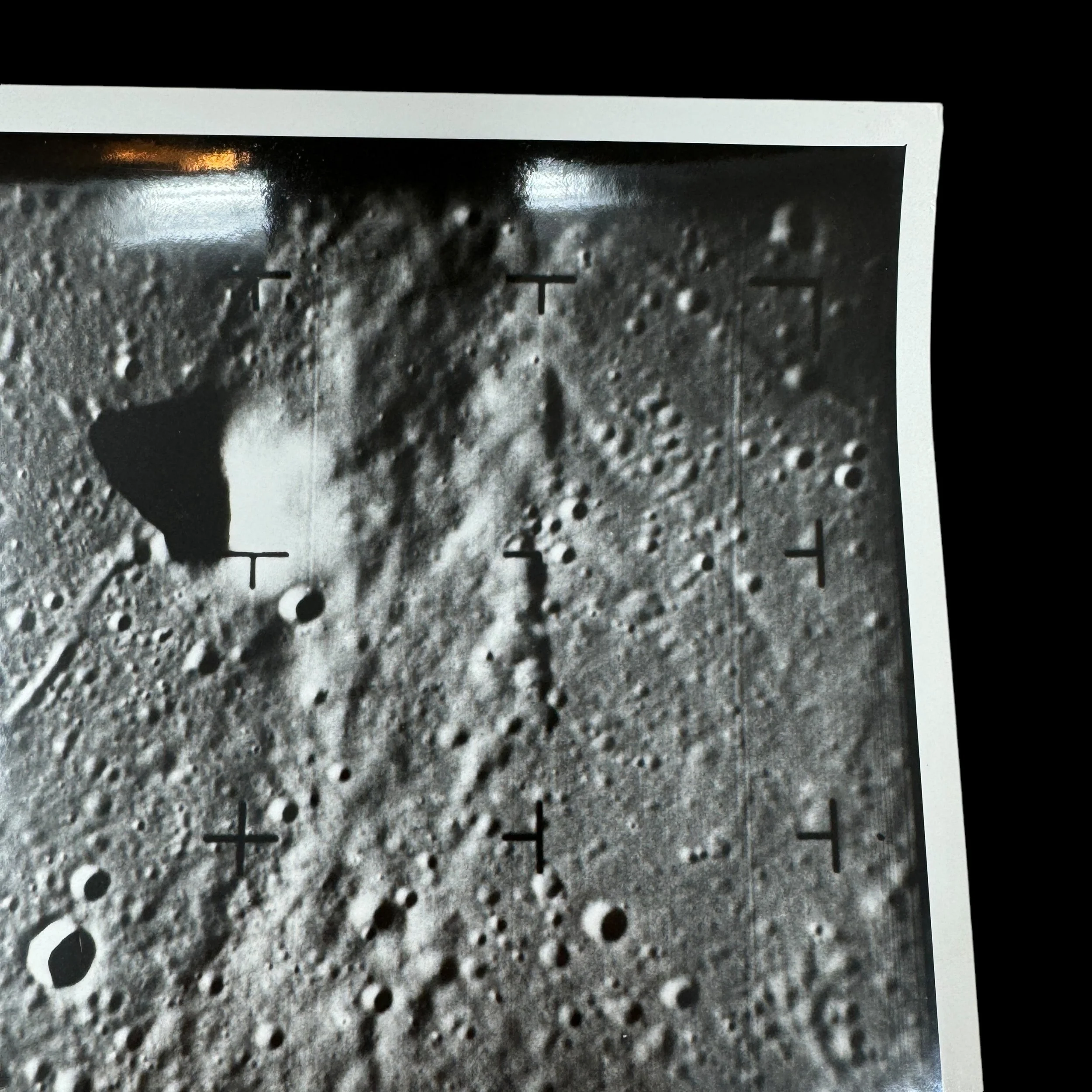

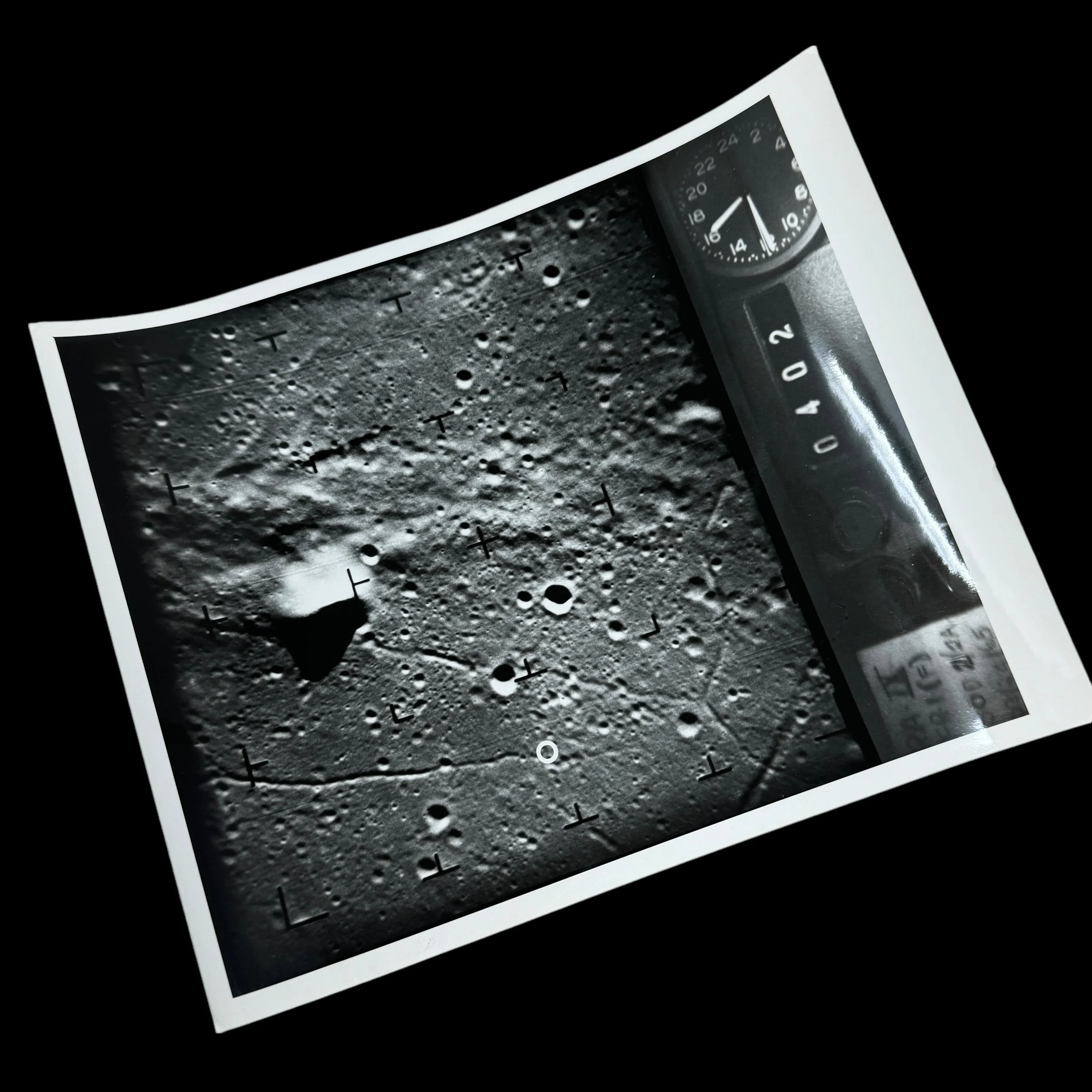

RARE! March 1963 NASA Ranger IX Type 1 Apollo Lunar Photograph Frame #0402

RARE! March 1963 NASA Ranger IX Type 1 Apollo Lunar Photograph Frame #0402

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A. and a full historical research write-up

Size: 8 × 10 inches

Mission: Ranger IX Mission - Lunar Photography Mapping

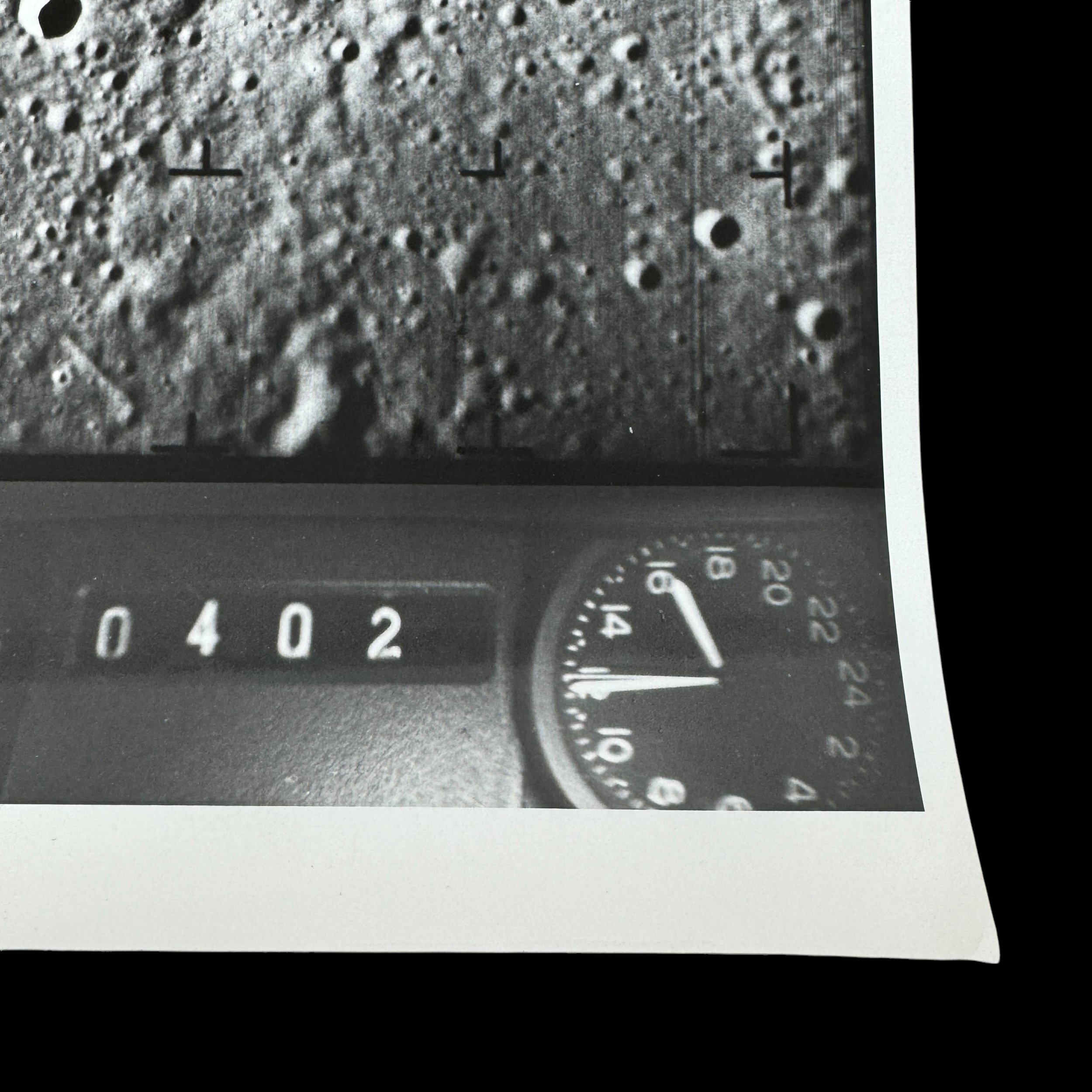

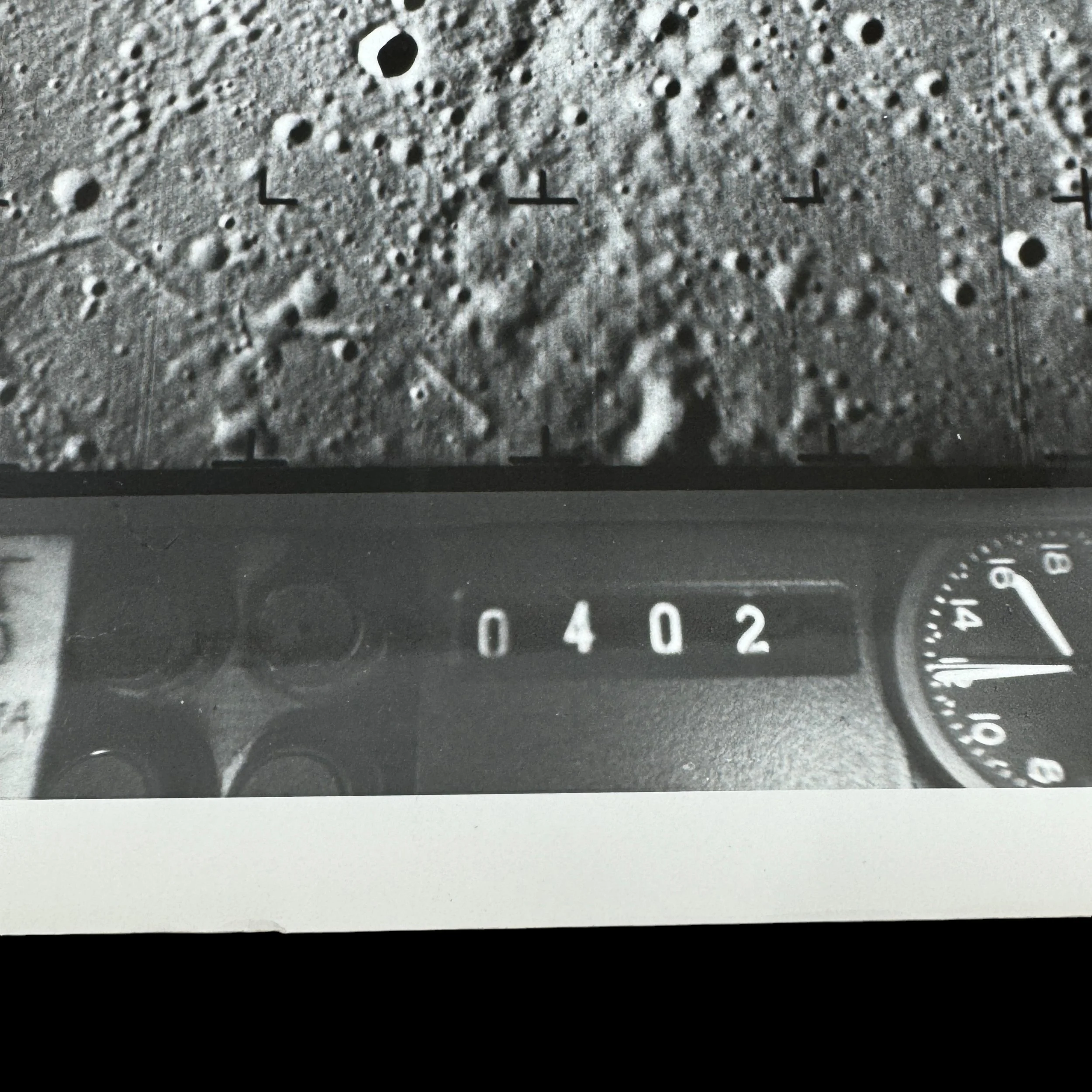

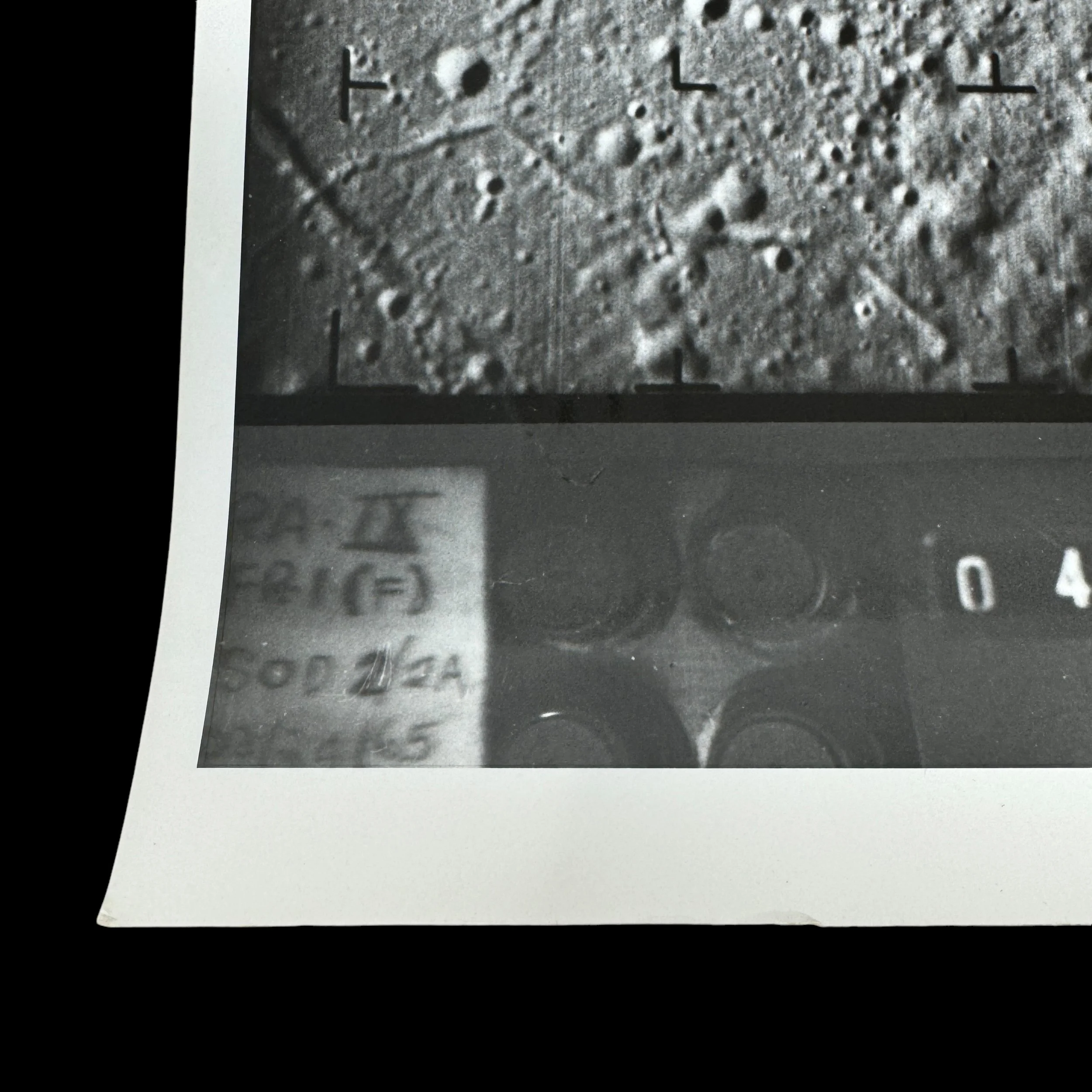

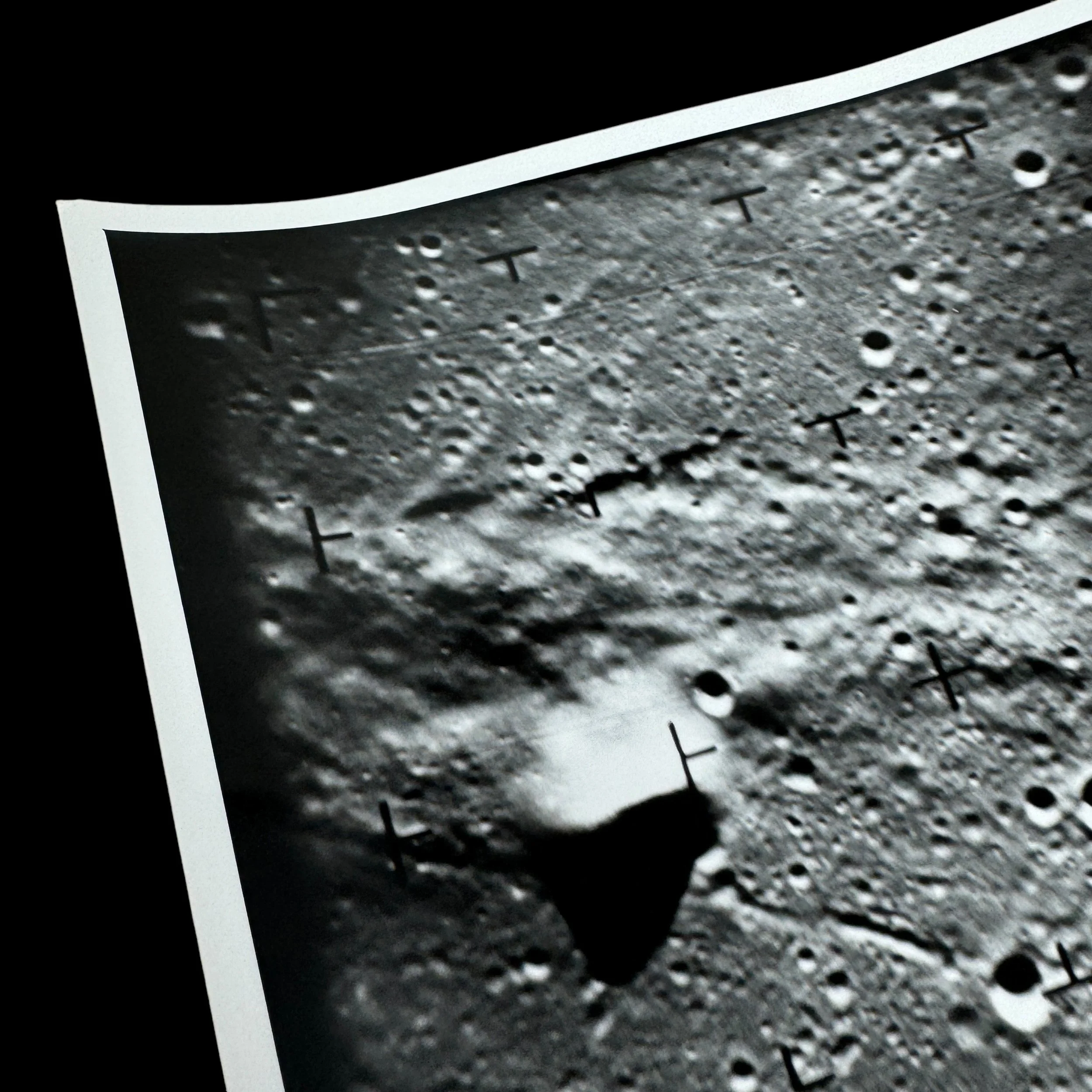

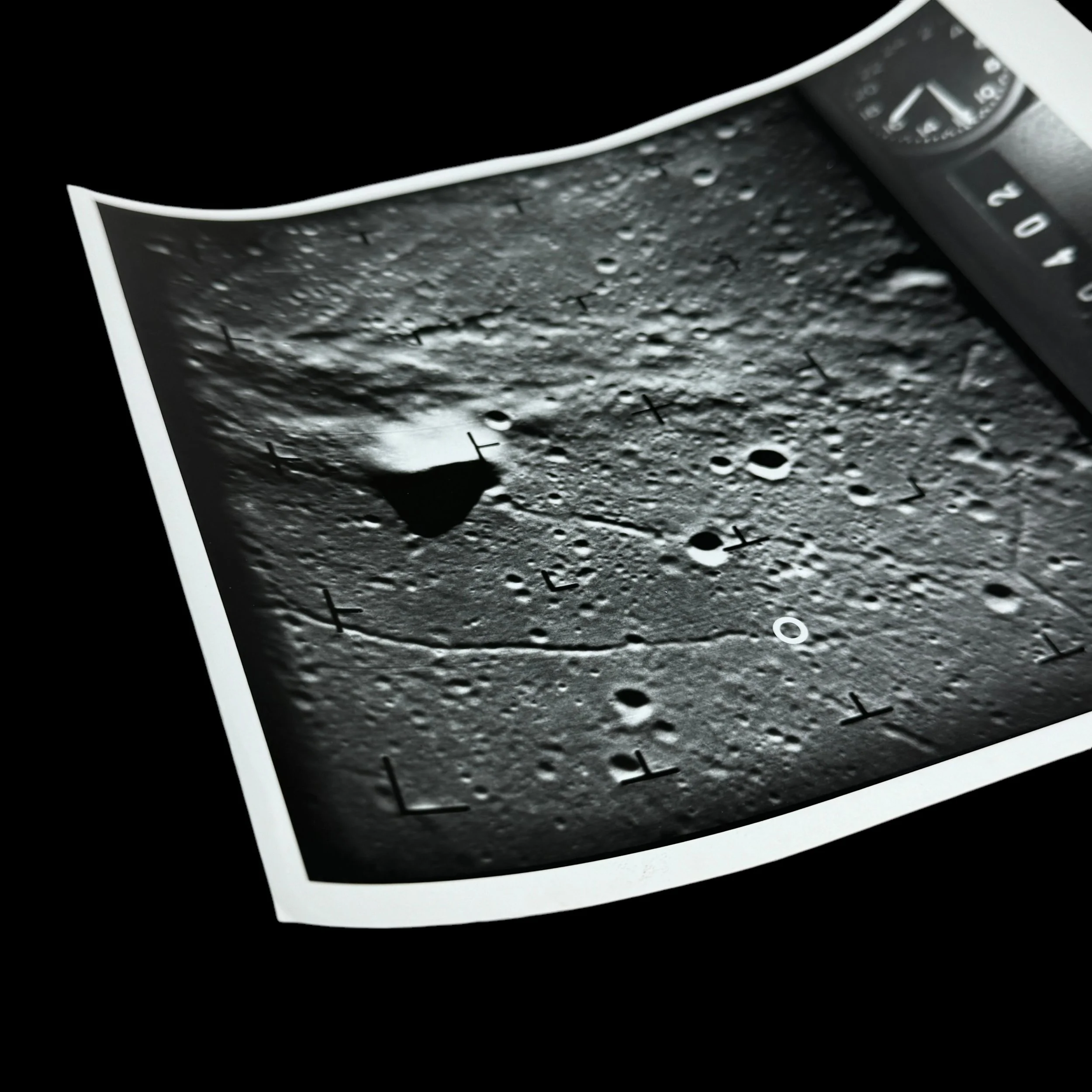

Photograph: Frame #0402 - Taken 43.9 seconds before impact in the crater Alphonsus.

Dated: 1965

This incredibly rare and museum-grade National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1965 dated Ranger IX lunar photograph is an original TYPE 1 NASA photograph developed shortly after the Ranger IX mission.

Ranger IX, launched on March 21, 1965, was the final mission of NASA's Ranger program, aimed at capturing high-resolution images of the Moon's surface before impact. The spacecraft was equipped with six television cameras—two full-scan and four partial-scan cameras—that transmitted over 5,800 images during its descent.

These cameras captured progressively higher resolution images as Ranger IX approached the lunar surface, with the final images taken just seconds before impact offering a resolution of about half a meter. The mission successfully transmitted live images back to Earth, marking the first time the public witnessed real-time lunar photography. These images provided crucial data for selecting safe landing sites for the upcoming Apollo missions, particularly in assessing the flatness and safety of the lunar maria.

This vintage NASA black-and-white glossy photograph features an extremely detailed image and also features the original stamp marking on the reverse. This type one lunar photograph is an incredible piece of early space and Apollo history.

The Ranger IX Mission: Pioneering Lunar Exploration Through Photography

The space race between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1960s spurred rapid technological advances in space exploration. One of NASA’s key programs in its early attempts to study the Moon was the Ranger series of missions. Ranger IX, the final mission of the Ranger program, marked a significant milestone in lunar exploration, as it provided high-quality close-up images of the Moon’s surface that were vital in preparing for the manned Apollo landings.

Among the most remarkable achievements of Ranger IX was its ability to transmit clear, detailed photographs of the Moon before it crash-landed on the surface, allowing scientists to study the lunar terrain in unprecedented detail. This essay will focus on the critical role of photography in the Ranger IX mission, detailing how the images were taken, transmitted, developed, and used to enhance humanity's understanding of the Moon.

The Objectives of the Ranger IX Mission

By the time Ranger IX was launched on March 21, 1965, the earlier Ranger missions had experienced a mix of successes and failures. The goal of the Ranger program was straightforward: to send spacecraft to the Moon to take detailed photographs of its surface before impact, thereby providing essential data for future lunar missions. Ranger IX, the last in the series, was designed to gather high-resolution images of potential Apollo landing sites, focusing on areas such as the lunar maria—flat, dark plains formed by ancient volcanic eruptions. These regions were of particular interest because they were considered safer landing zones for future manned missions.

Ranger IX was equipped with a suite of sophisticated cameras, which were the central instruments for the mission. The success of the mission depended heavily on these cameras functioning flawlessly during the descent, as there would be no opportunity for adjustments or corrections once the spacecraft began its final approach to the Moon.

The Camera System on Ranger IX

Ranger IX’s camera system was a technological marvel for its time, specifically designed to capture close-up images of the lunar surface in its final moments before impact. The spacecraft was equipped with six television cameras—two full-scan and four partial-scan cameras. These cameras were part of the Block III series of spacecraft that incorporated improved imaging technology over earlier Ranger models. The cameras operated at different resolutions and fields of view to ensure that they could capture a wide array of images, ranging from broader landscape shots to close-up views of the lunar surface.

The full-scan cameras captured images at a resolution of 1150 lines per frame (a high resolution for the time), while the partial-scan cameras worked at 300 lines per frame. The partial-scan cameras were capable of taking more images in rapid succession, compensating for the lower resolution by providing greater coverage of the surface in the final moments of the descent. Together, the six cameras provided a continuous stream of images, each with progressively higher resolution as Ranger IX moved closer to the Moon.

What set Ranger IX apart from previous missions was its ability to transmit live images of the lunar surface back to Earth. In total, the spacecraft sent back more than 5,800 high-resolution photographs over a period of about 19 minutes, providing a wealth of data for scientists to study.

The Photographic Sequence and Transmission

The success of Ranger IX’s photographic mission depended on the timing and precision of its descent. The spacecraft was designed to begin taking pictures at an altitude of about 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles) above the lunar surface. As the spacecraft plummeted toward the Moon, it continuously sent back images, with the resolution improving as the distance decreased. The final images, taken moments before impact, had a resolution of about half a meter, providing an incredibly detailed view of the lunar terrain.

The cameras on Ranger IX were equipped with Vidicon tubes, which were early forms of television camera tubes that converted the optical image into electrical signals. These signals were then transmitted back to Earth via a high-gain antenna aboard the spacecraft. The transmission of these images relied on the Deep Space Network, a system of radio antennas that NASA had developed to communicate with distant spacecraft. Ranger IX transmitted its images at a rate of 25 images per second, a remarkable feat given the technology available at the time.

One of the most exciting aspects of the mission was that the images were broadcast live on television. This was the first time that the public could witness such detailed photographs of the Moon’s surface in real-time, as Ranger IX hurtled toward its final destination. The dramatic nature of these images captured the public’s imagination and fueled the excitement surrounding lunar exploration.

Development and Analysis of the Photographs

Once the images were transmitted back to Earth, they were processed and analyzed by teams of scientists and engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. The data from the Vidicon cameras were converted into photographic prints for further study. This process involved scanning the transmitted images, which had been received as electrical signals, and developing them as photographic negatives. The negatives were then used to produce prints that could be analyzed for details about the lunar surface.

The images revealed much about the Moon that had previously been unknown. Ranger IX’s photographs showed a rugged, cratered landscape, with large impact craters and a variety of surface textures. The detailed images allowed scientists to assess the topography of the Moon and helped them identify potential landing sites for future missions, including the Apollo program.

One of the key uses of the Ranger IX photographs was to examine the suitability of the lunar maria as landing sites. The flat plains, which appeared relatively free of large boulders or obstacles, were deemed safe for the Apollo Lunar Module to land. This information was crucial for NASA’s planning of future manned missions, as the safety of the landing site was a top priority for the success of the Apollo program.

The Legacy of Ranger IX’s Photographs

The photographs taken by Ranger IX had a lasting impact on lunar exploration. They provided the most detailed images of the Moon up to that point and were instrumental in shaping the direction of future lunar missions. The success of Ranger IX helped lay the groundwork for the Surveyor and Lunar Orbiter missions, which provided additional data and images in preparation for the manned Apollo landings.

Moreover, Ranger IX demonstrated the feasibility of using high-resolution photography as a tool for planetary exploration. The mission’s success validated the use of spacecraft to gather close-up images of distant celestial bodies, a technique that would become a cornerstone of future space missions, from Mars rovers to deep-space probes.

The live transmission of images from Ranger IX also marked a turning point in public engagement with space exploration. The ability to broadcast images from space in real-time captivated audiences and helped foster a greater public interest in NASA’s missions. This set the stage for the dramatic television broadcasts of the Apollo Moon landings, which would become iconic moments in the history of space exploration.

Ranger IX’s mission over the lunar surface was a pioneering achievement in the history of space exploration, with photography playing a central role in its success. The high-resolution images captured by Ranger IX provided invaluable data for scientists, helping to prepare for the Apollo missions and advancing our understanding of the Moon’s surface. The mission demonstrated the power of photography as a scientific tool, proving that detailed images of distant worlds could be obtained and used to shape the future of space exploration.

The success of Ranger IX also highlighted the importance of public engagement in space exploration, as the live transmission of images from the mission inspired and excited people around the world. Ranger IX’s legacy lives on in the continued use of spacecraft imaging to explore and understand our solar system, a legacy that began with the first detailed photographs of the Moon’s rugged and mysterious surface.