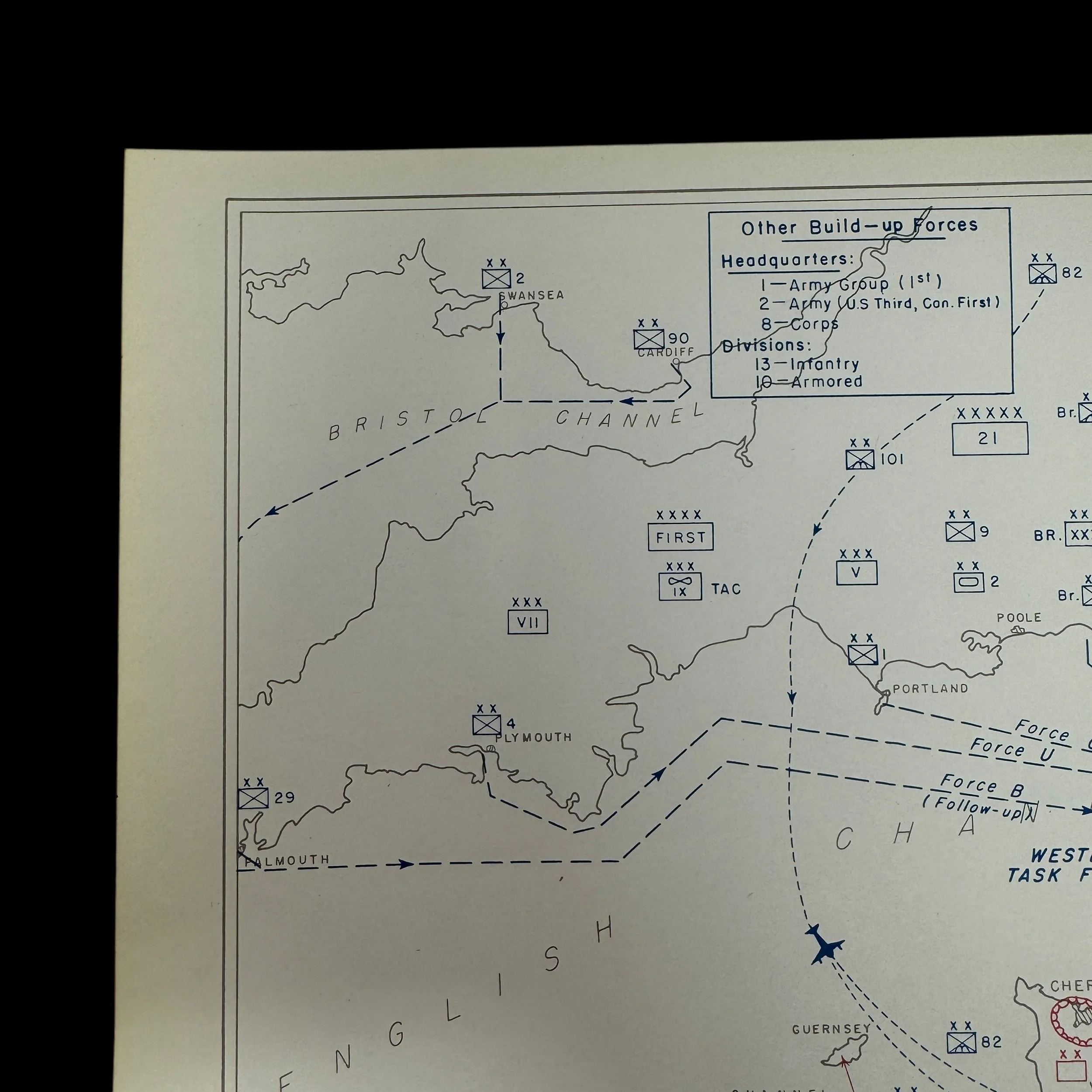

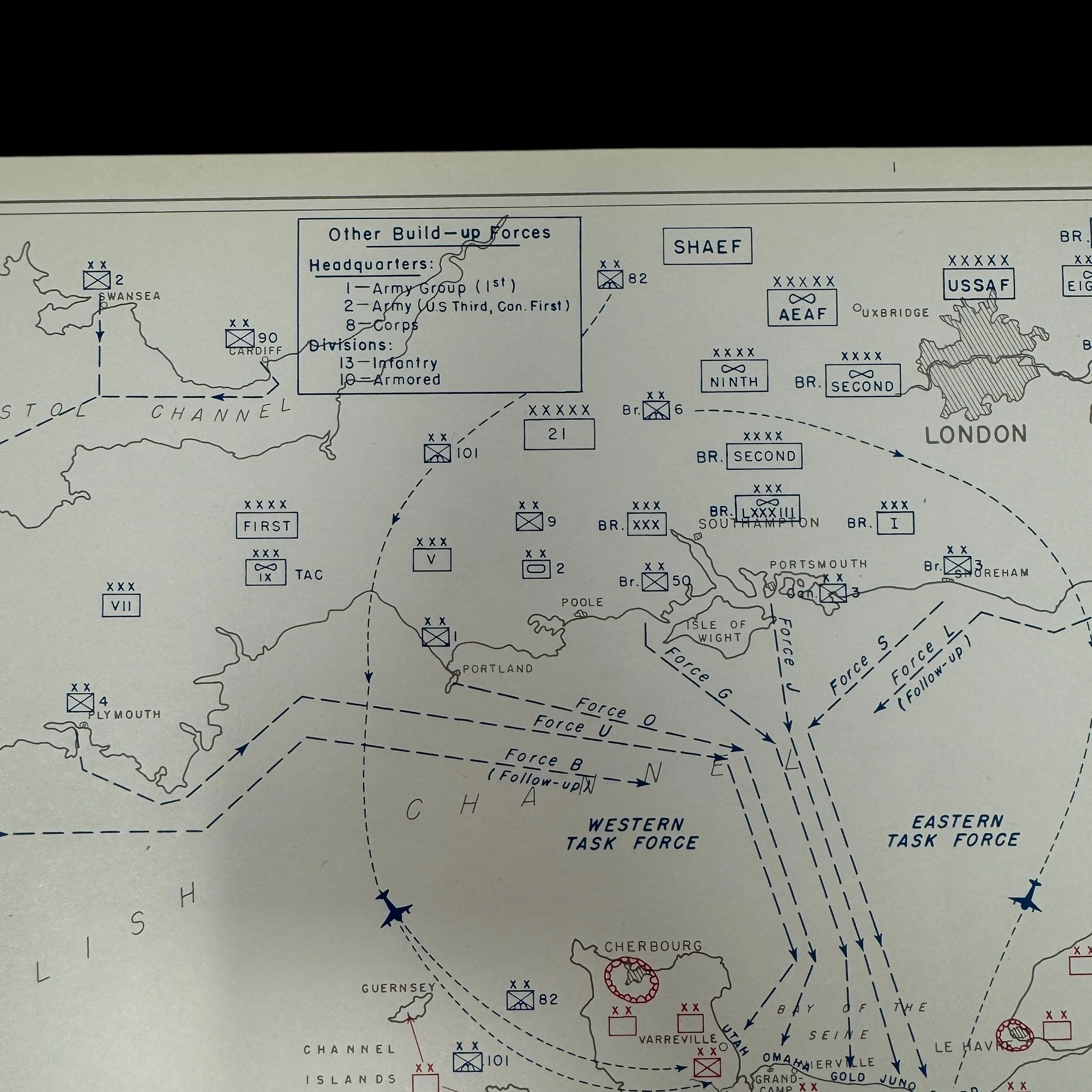

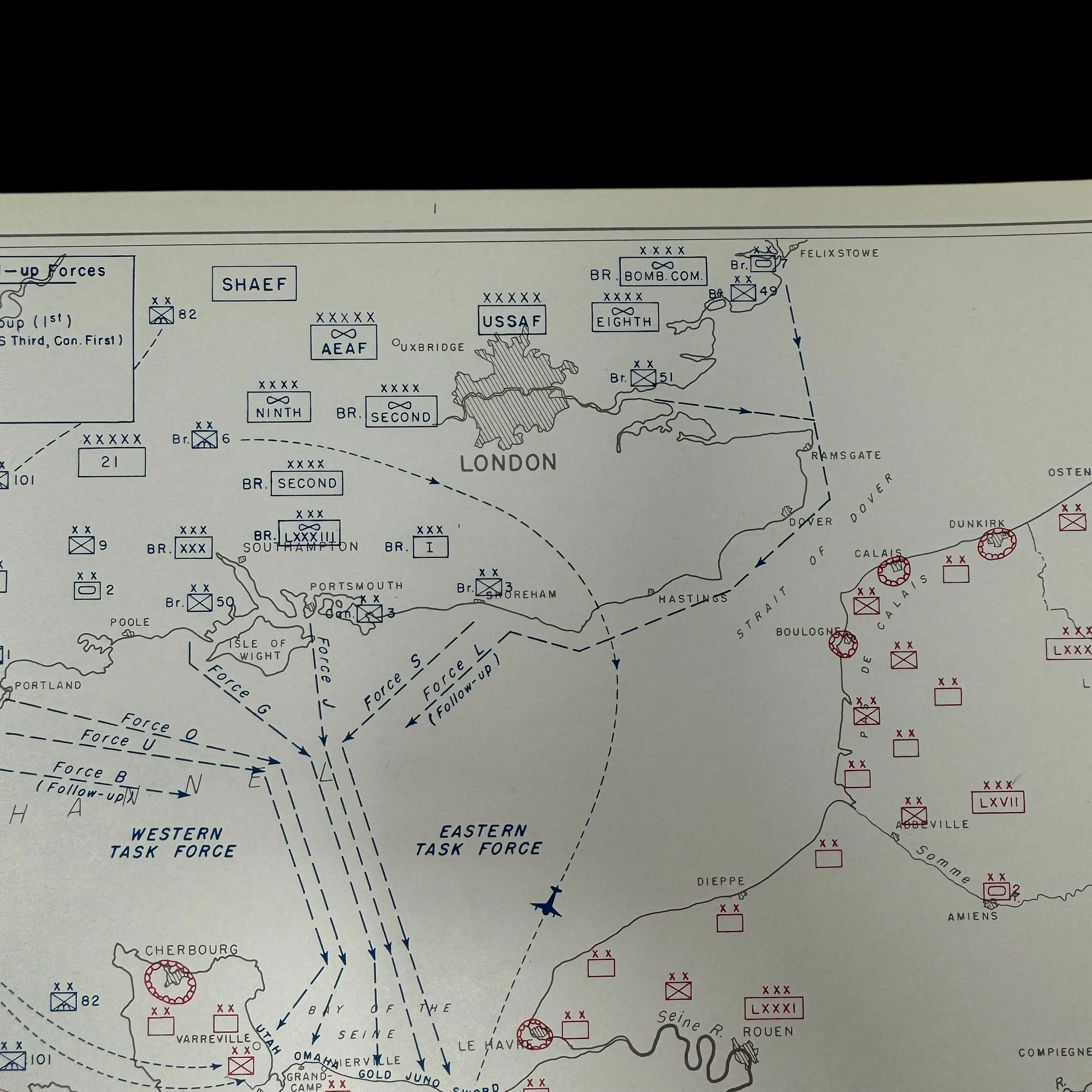

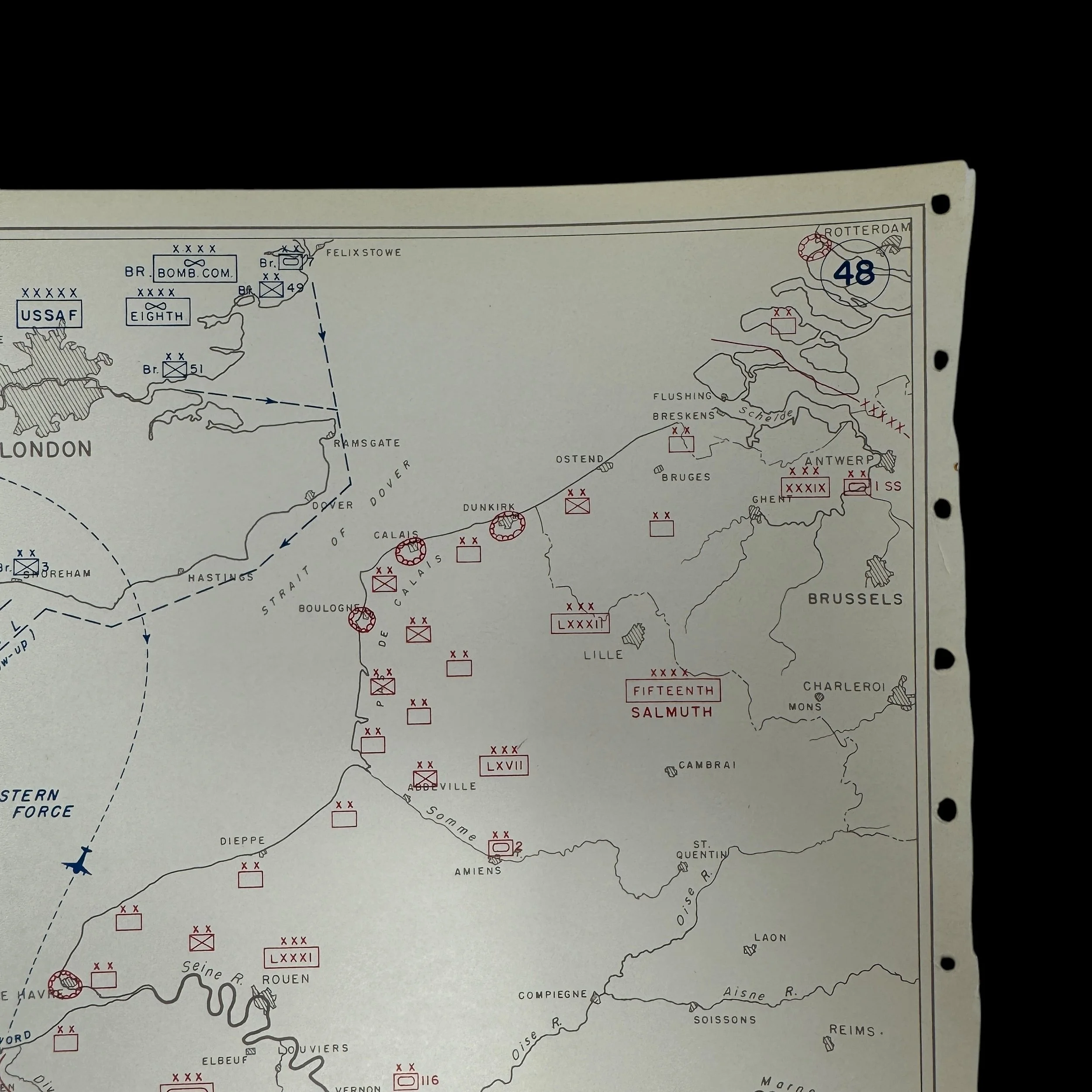

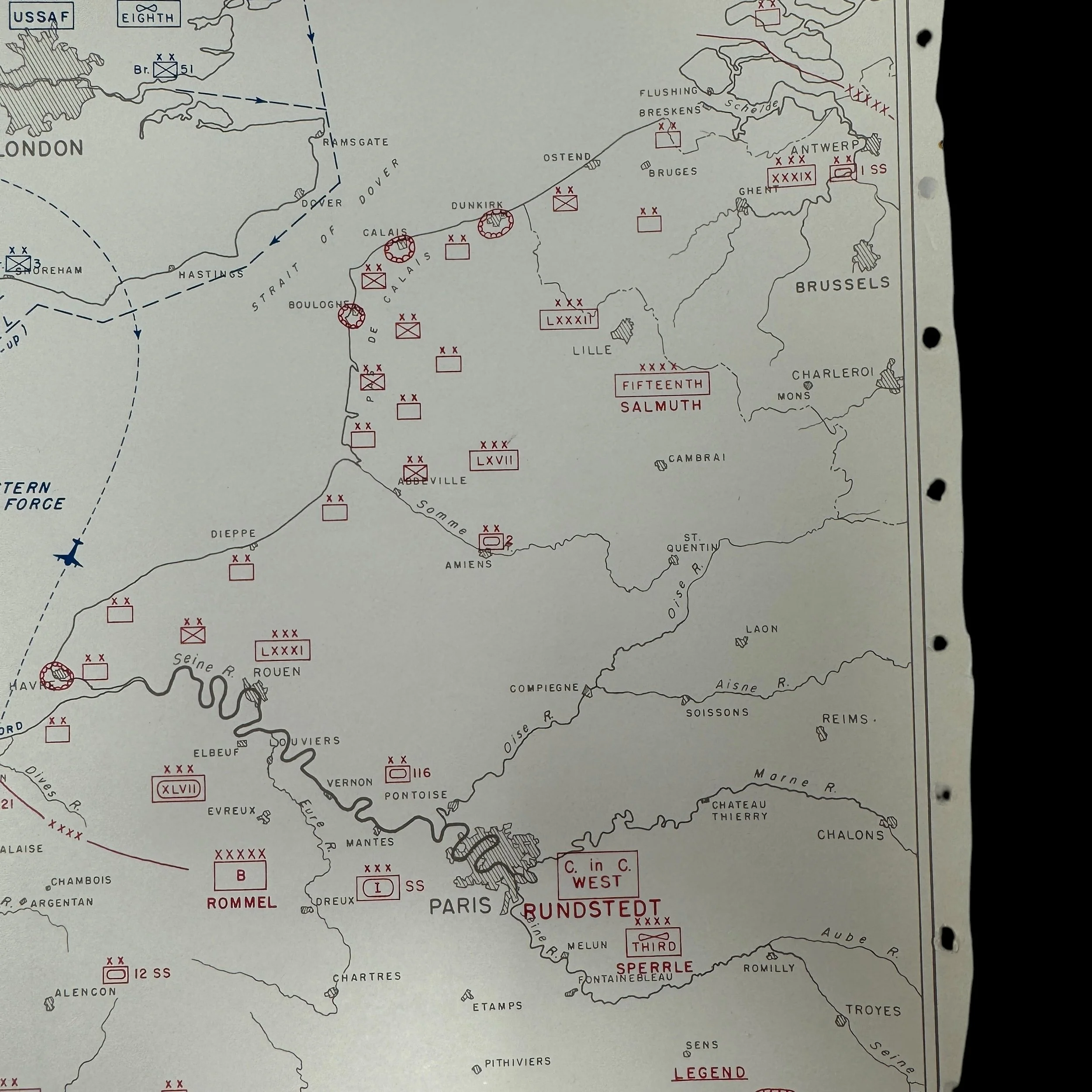

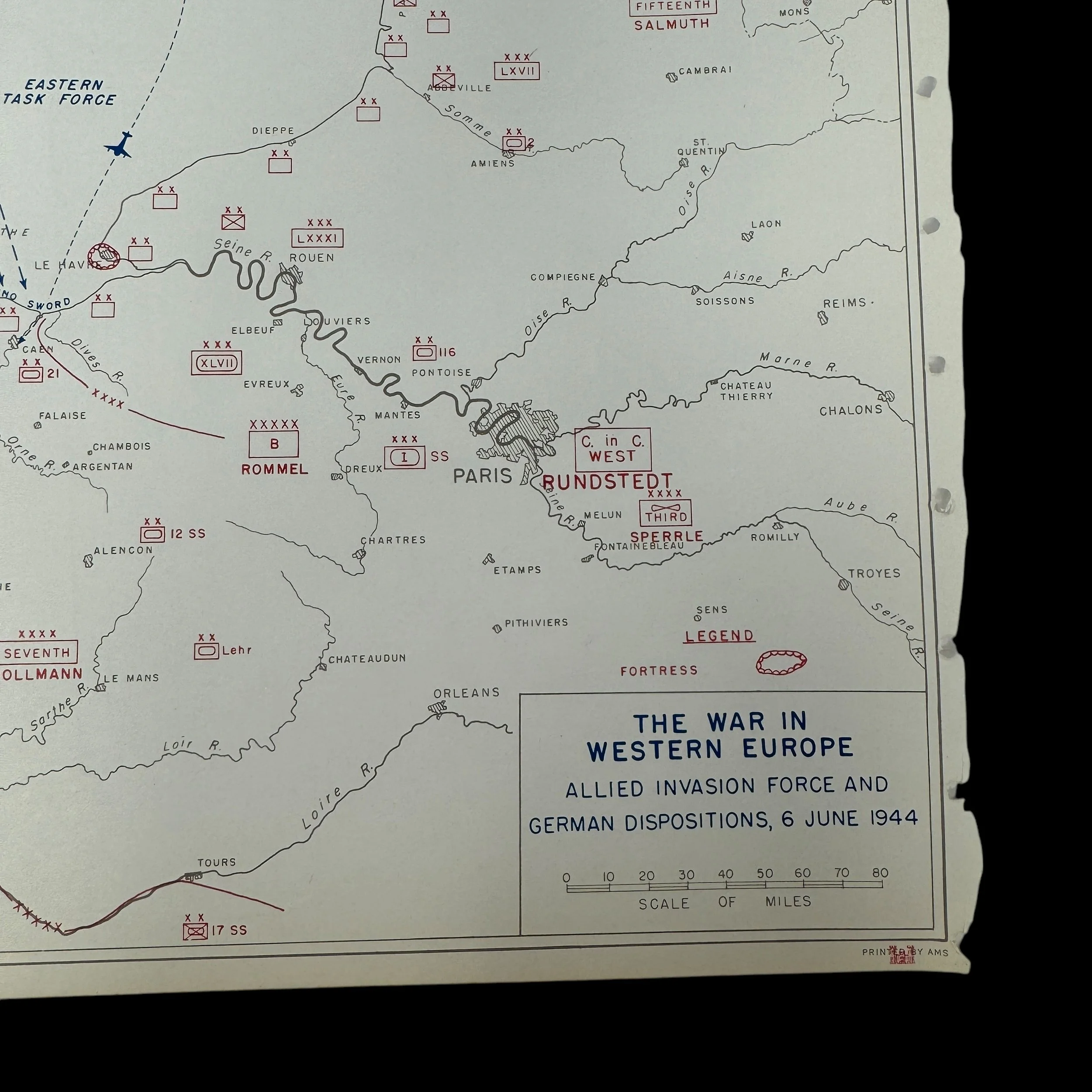

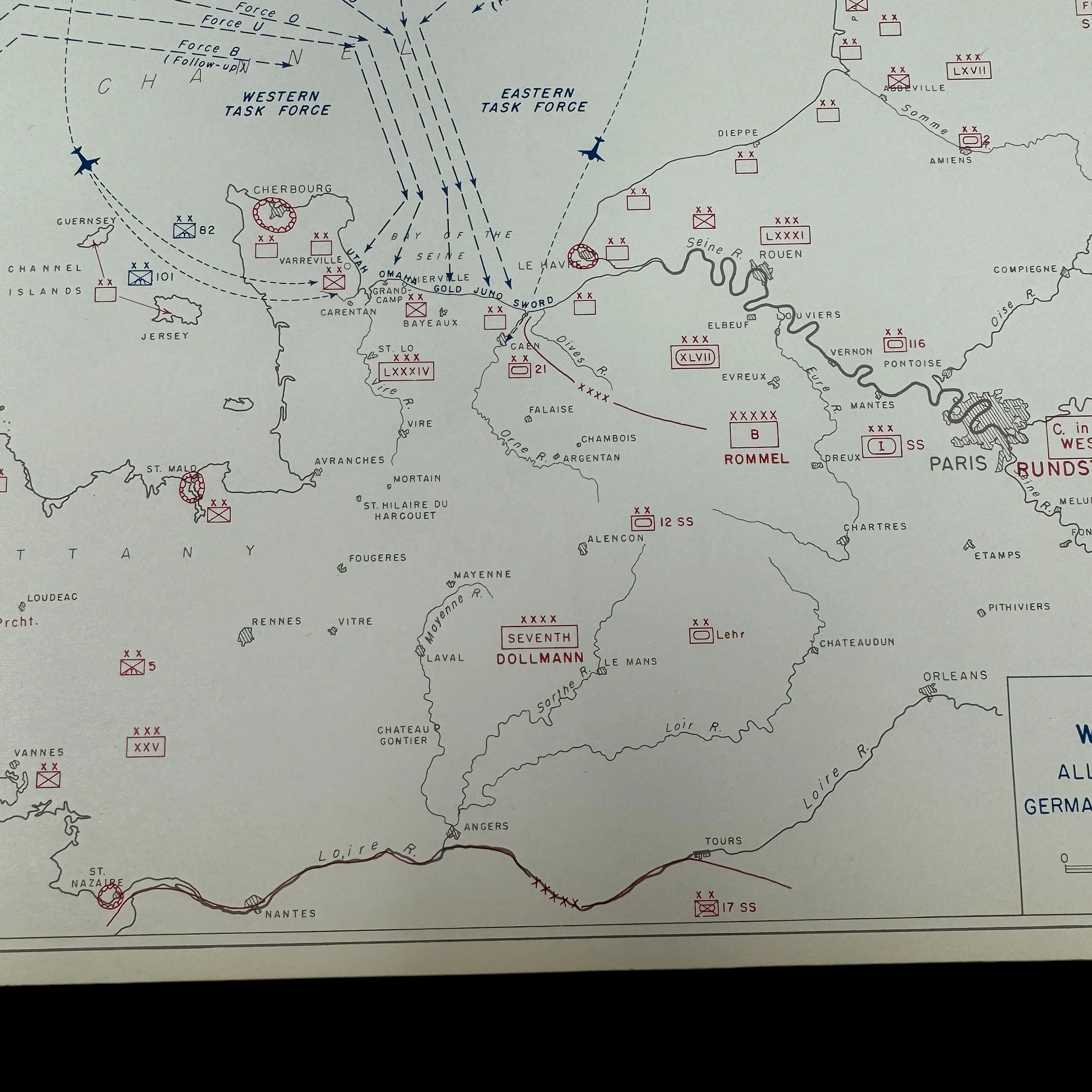

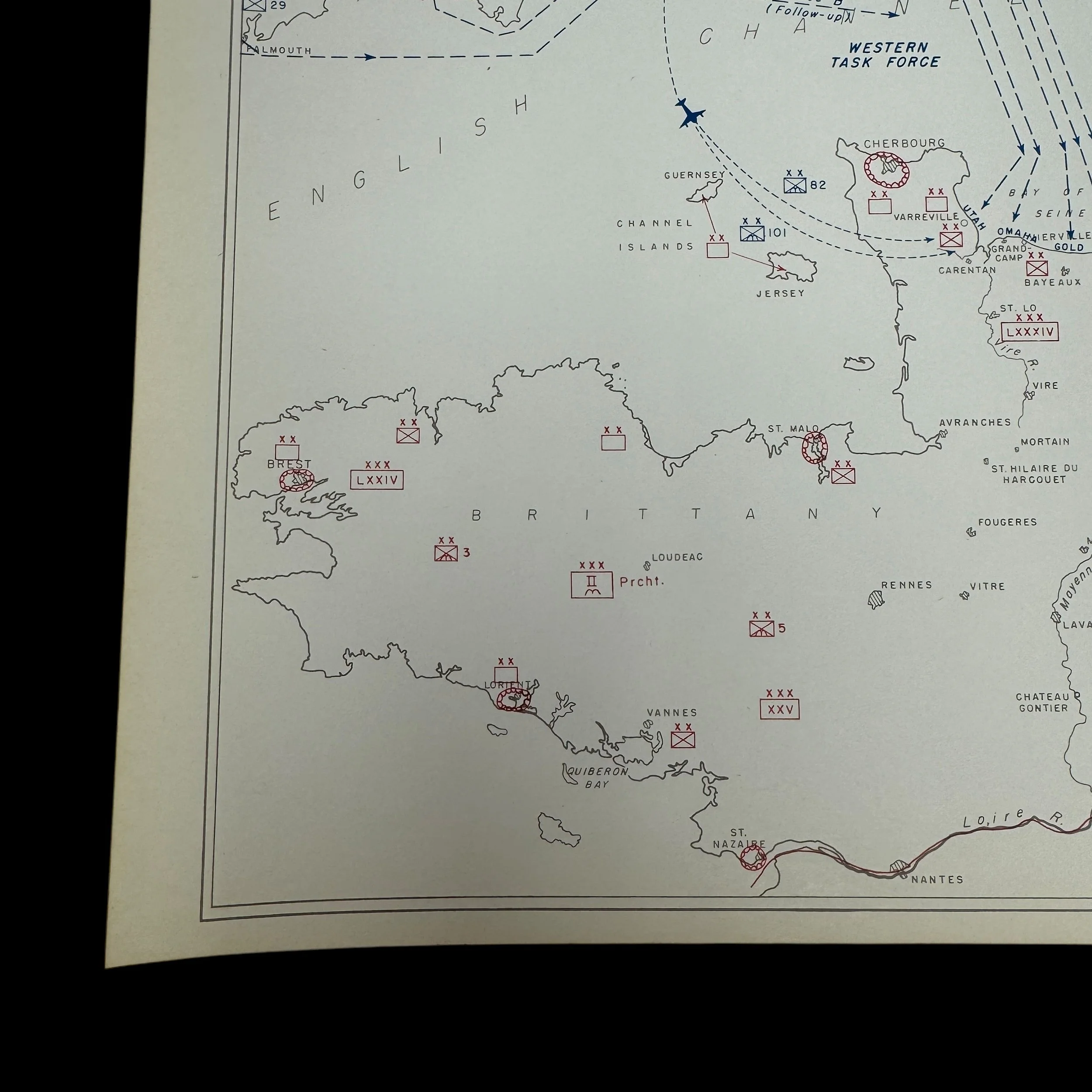

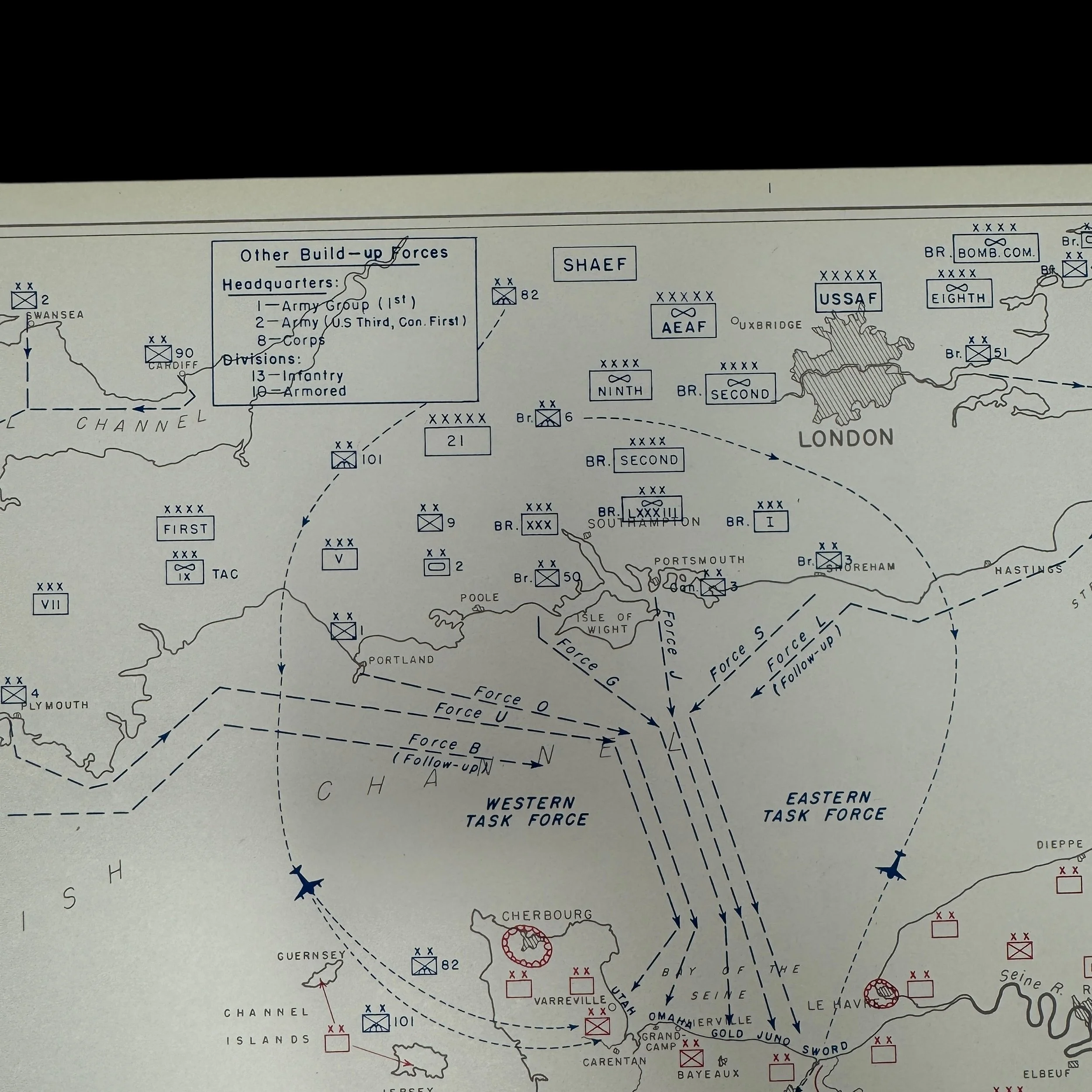

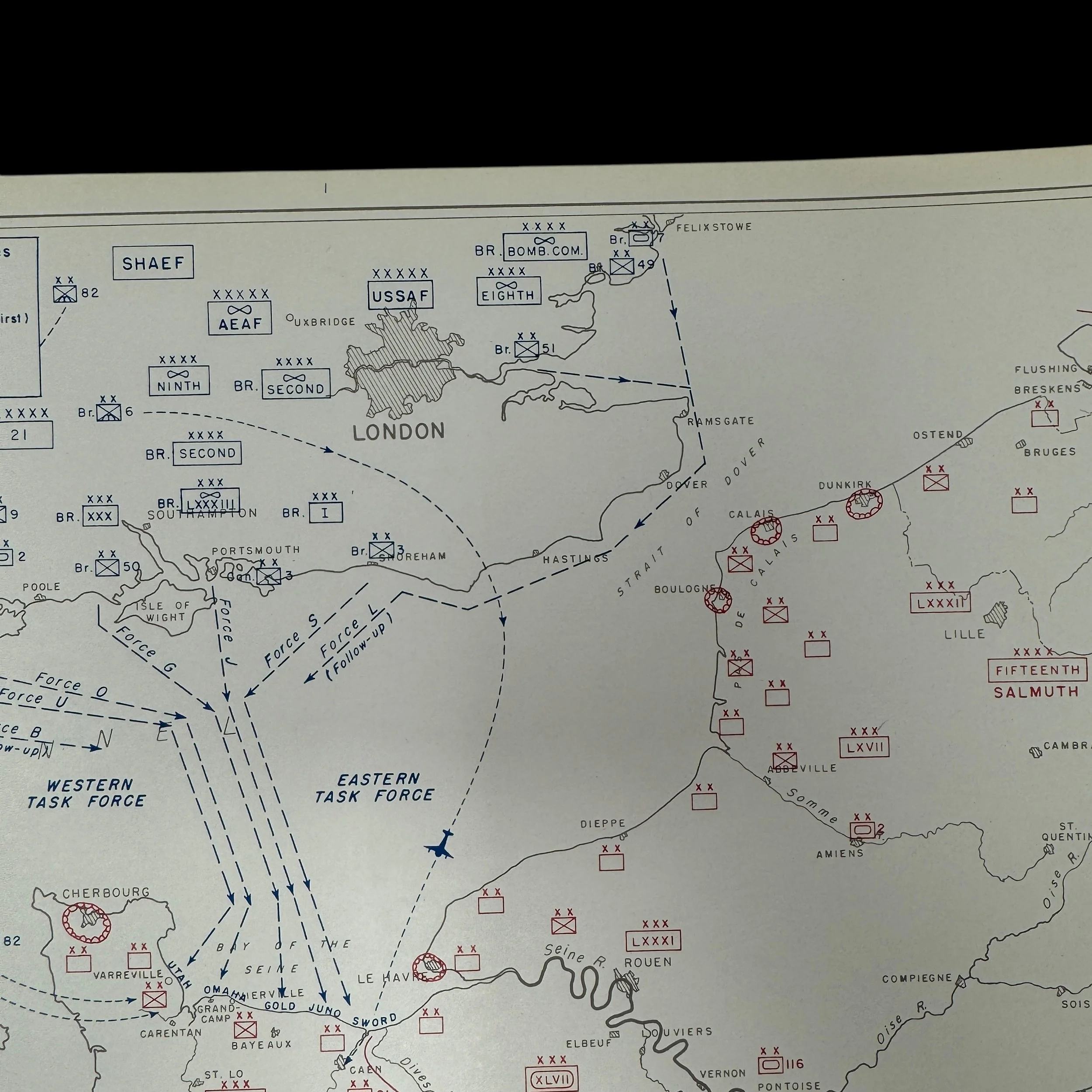

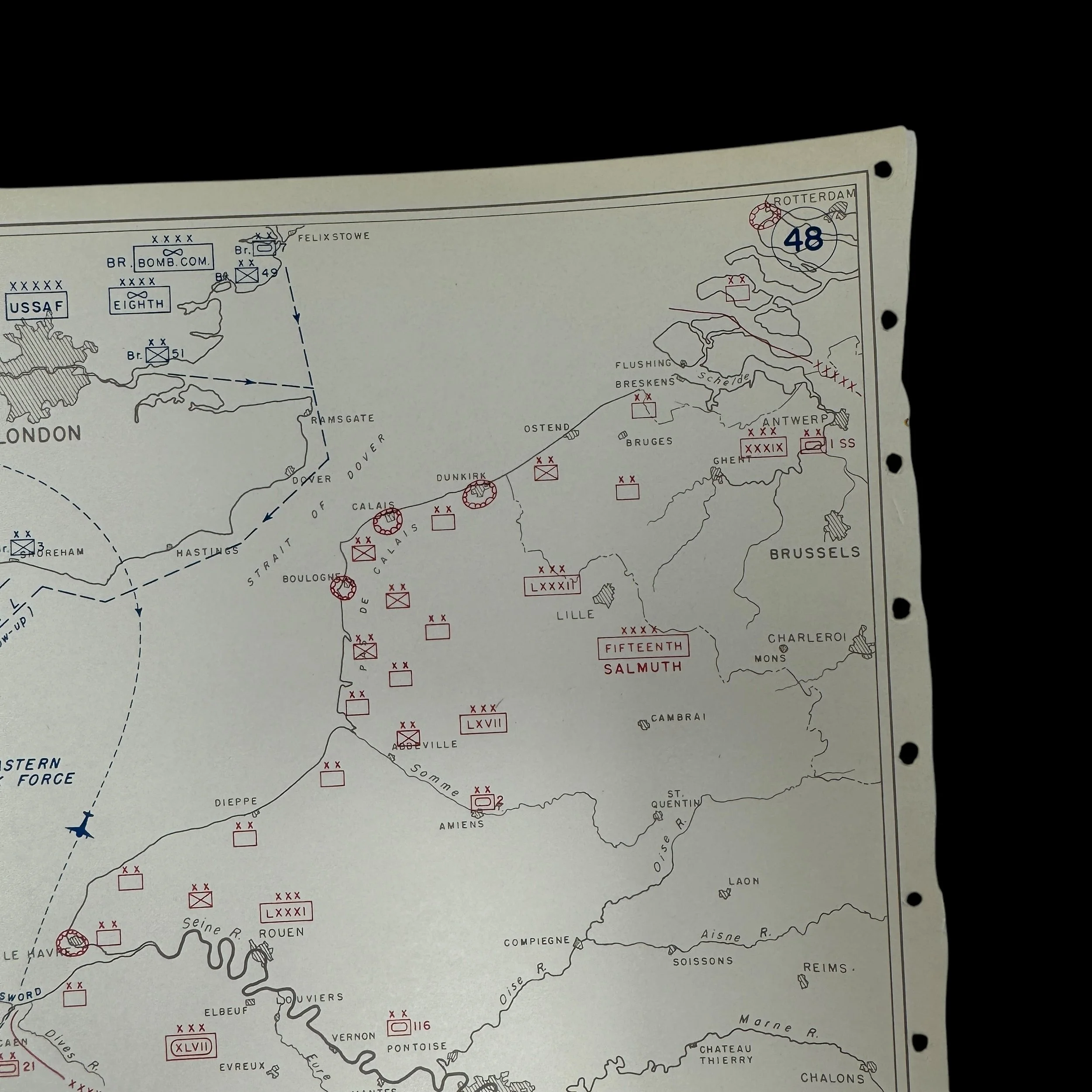

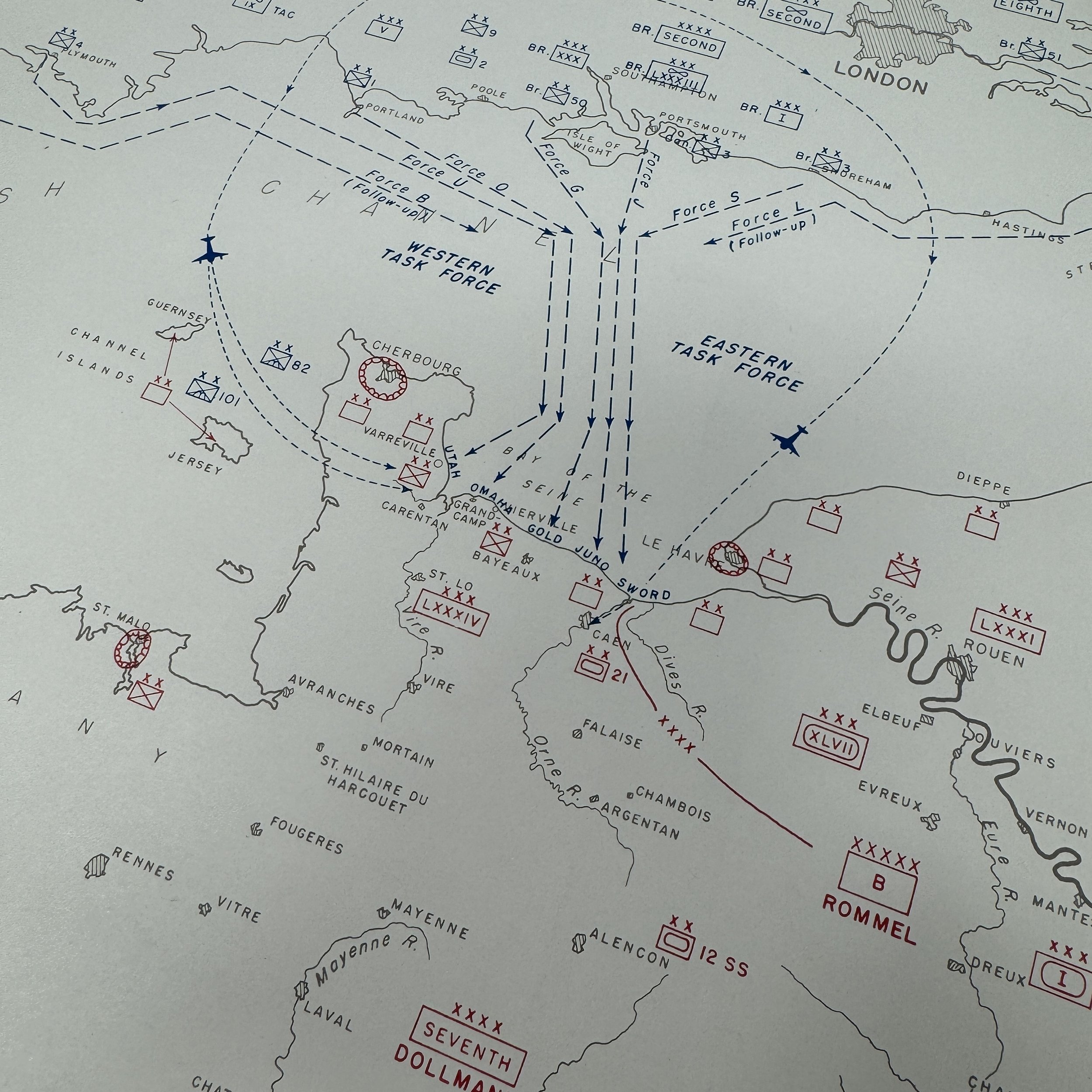

Original 1953 United States Military Academy West Point World War II Military Campaign Operational Study Map Plate (D-Day Operation Overlord - Allied Invasion Force and German Dispositions)

Original 1953 United States Military Academy West Point World War II Military Campaign Operational Study Map Plate (D-Day Operation Overlord - Allied Invasion Force and German Dispositions)

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A. and a full historical write-up

Type: Original 1953 United States Military Academy West Point World War II Military Campaign Operational Study Map Plate

Produced: Special map plate made by the Department of Military Art and Engineering (United States Military Academy - West Point)

Campaign: Western European Theater - Normandy, France

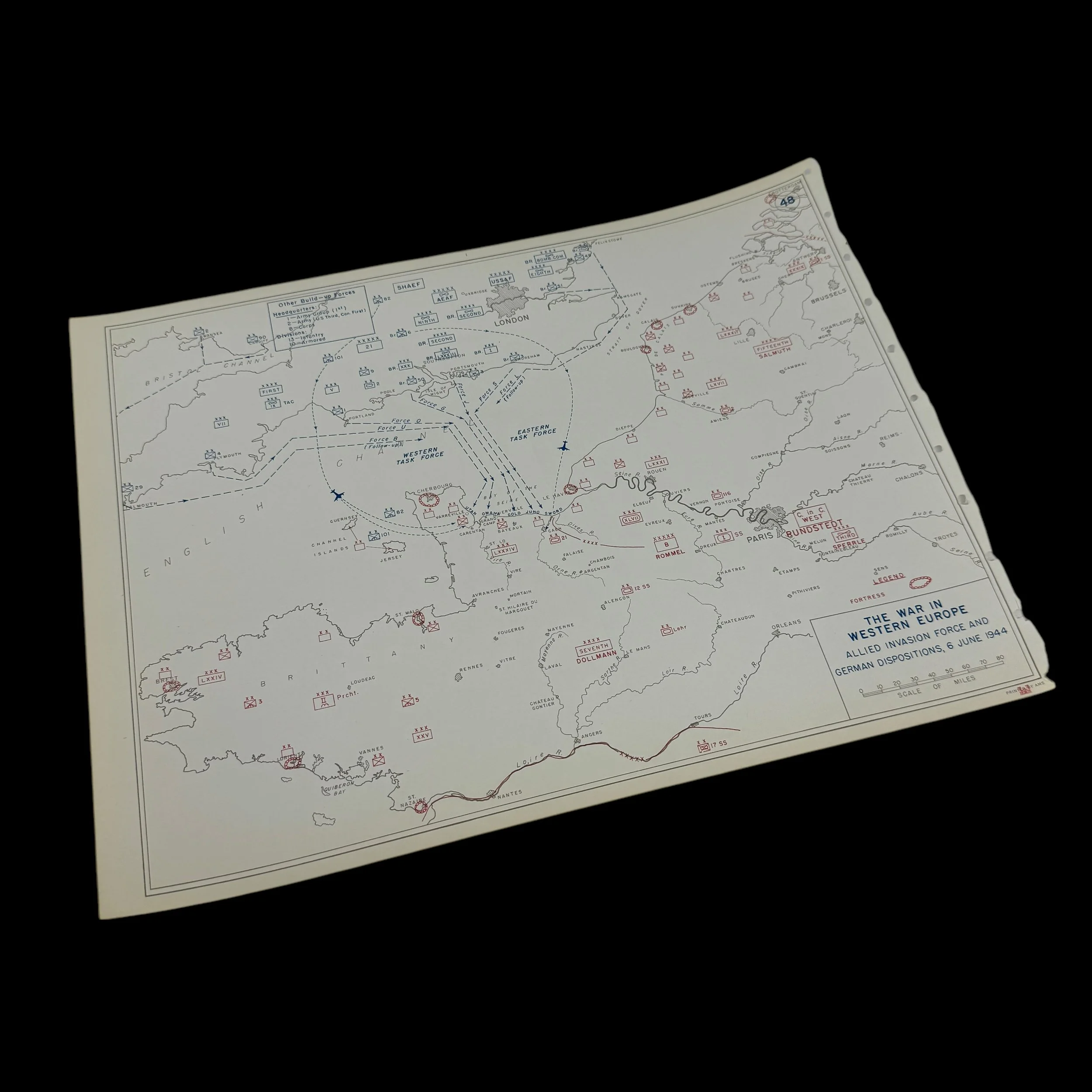

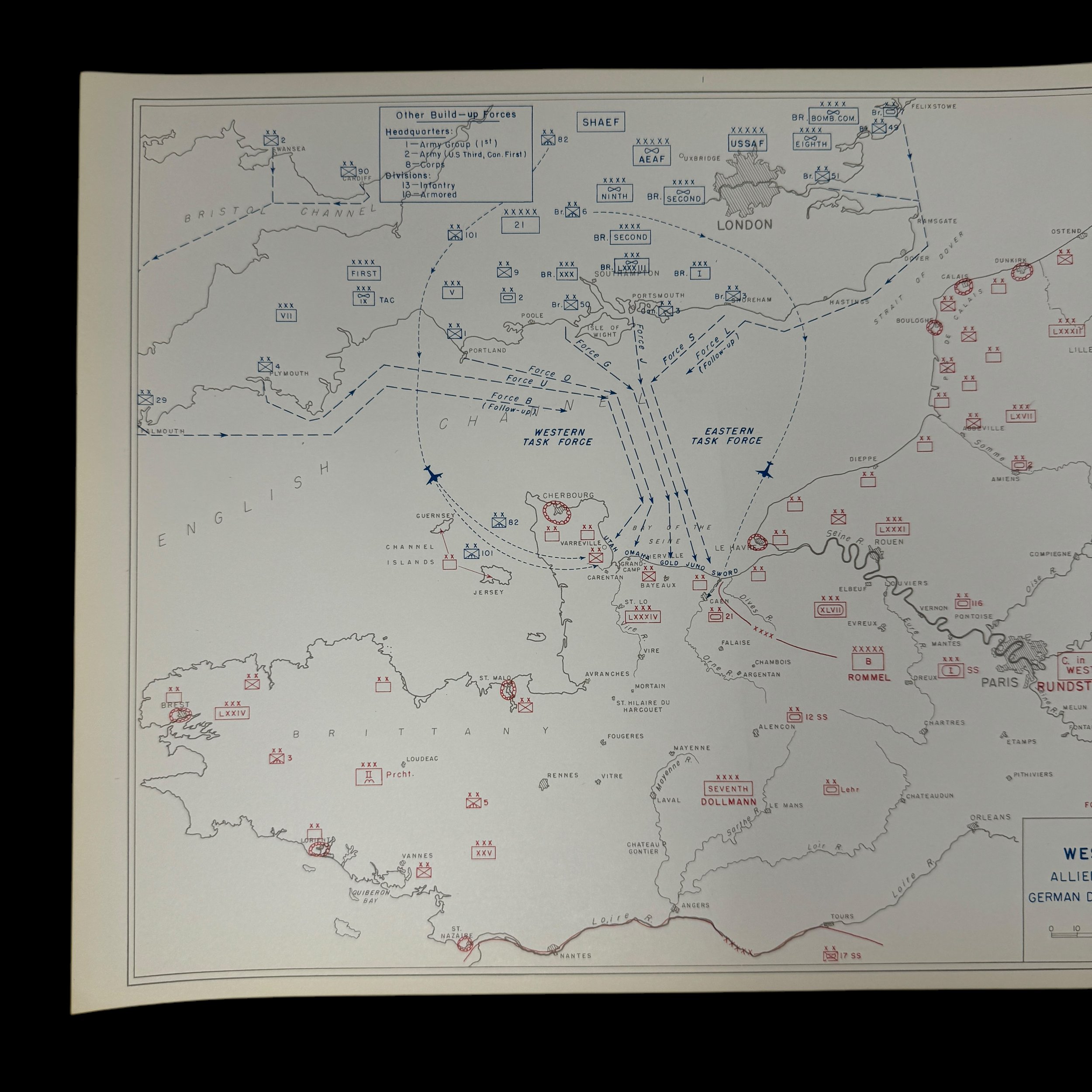

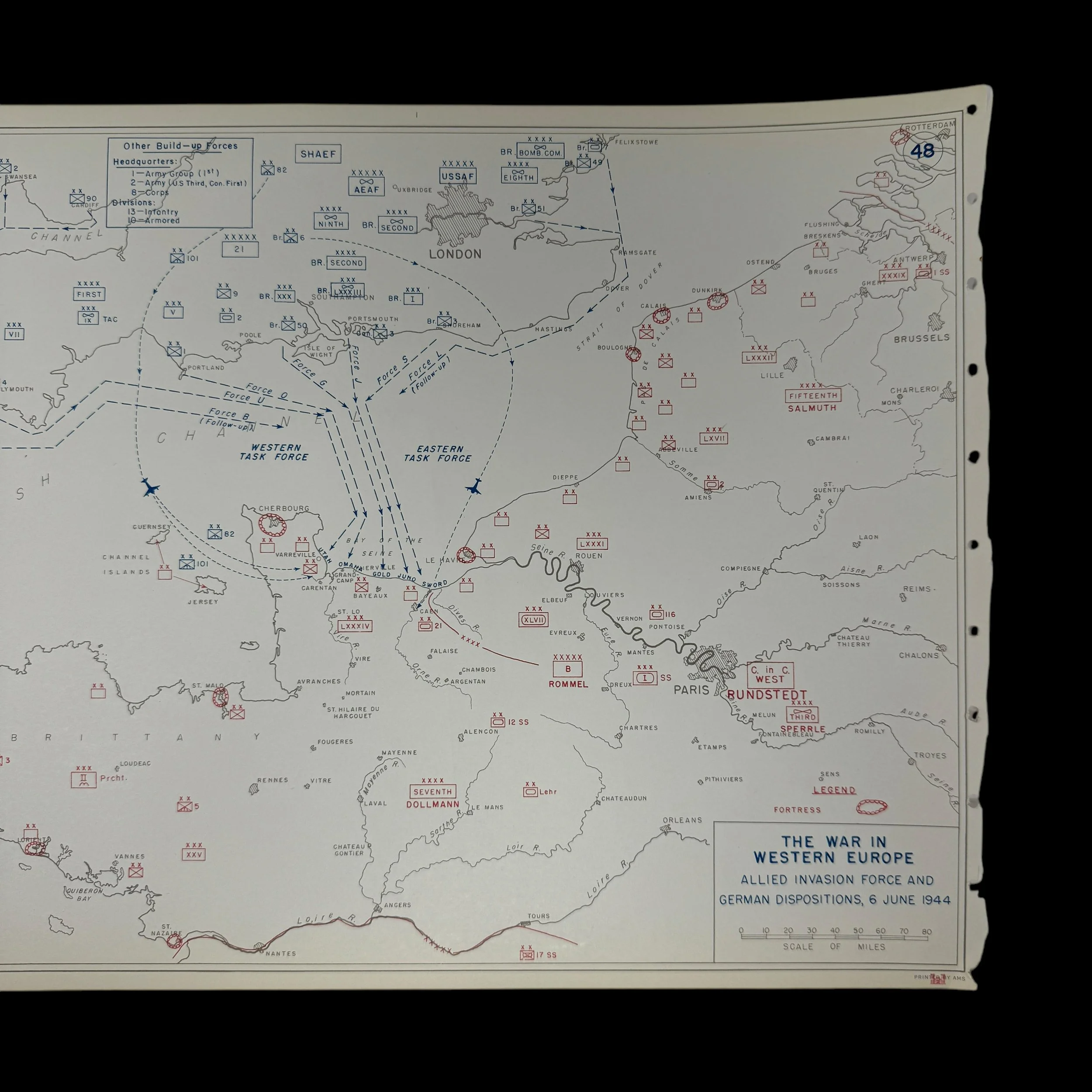

Battle/Operation: D-Day Operation Overlord - Allied Invasion Force and German Dispositions June 6th, 1944

Size: 14 × 10.5 inches

In the years following World War II, the United States Military Academy at West Point faced the monumental task of preparing future military leaders for an era of evolving warfare. By 1953, the Academy had integrated World War II operational campaign military maps into its curriculum as vital tools for studying the strategies and tactics employed during the conflict. These maps, which had served as critical planning and operational resources during the war, became essential teaching aids, allowing cadets to analyze real-world applications of military theory, refine their strategic thinking, and adapt lessons from the past to modern military challenges. The decision to incorporate these maps into training programs reflected the Academy's commitment to learning from history and enhancing the intellectual rigor of its officer education.

During World War II, operational campaign maps were indispensable to the planning and execution of military strategies. These maps were meticulously crafted, often combining topographical details, troop movements, supply routes, and key infrastructure information. Commanders relied on them to visualize battlefields, anticipate enemy actions, and coordinate large-scale operations across diverse terrains. Maps such as those used in the Normandy landings, the Battle of the Bulge, and the Pacific theater illustrated the complexity and dynamism of modern warfare. By 1953, these maps had become artifacts of historical and educational significance, offering a window into the decision-making processes of the war’s most pivotal moments.

At West Point, these maps were used to teach cadets about operational planning, logistical coordination, and the execution of combined arms strategies. Instructors often began by presenting maps from campaigns such as Operation Overlord or the Battle of Midway, highlighting the strategic considerations that shaped these operations. For example, the intricate plans for the Normandy invasion, which involved coordinating naval, air, and ground forces, demonstrated the importance of synchronization in multi-domain warfare. Cadets analyzed how Allied commanders used maps to identify key objectives, such as securing beaches, establishing supply lines, and advancing inland, all while countering German defenses along the Atlantic Wall.

One of the primary ways these maps were utilized was through the study of operational art—a concept that bridges the gap between strategy and tactics. Operational art involves the design and execution of campaigns to achieve strategic goals within the constraints of time, space, and resources. World War II operational maps provided cadets with concrete examples of this concept in action. By examining the geographical constraints, enemy dispositions, and logistical challenges depicted on these maps, cadets could assess how commanders made decisions to achieve their objectives while minimizing risks and exploiting opportunities.

Moreover, the maps served as case studies for analyzing the successes and failures of wartime operations. For instance, cadets studying the Battle of the Bulge examined maps that detailed German troop movements, the positioning of Allied forces, and the topographical challenges of the Ardennes Forest. This analysis helped them understand how Allied commanders responded to the surprise offensive and ultimately turned the tide in their favor. Similarly, maps from the Pacific theater, such as those depicting the island-hopping campaign, illustrated the strategic importance of selecting objectives that balanced the need for progress with the necessity of conserving resources and minimizing casualties.

Instructors at West Point also used these maps to emphasize the importance of logistics in modern warfare. World War II had demonstrated that the ability to sustain armies through effective supply chain management was as crucial as battlefield tactics. Maps showing supply routes, transportation hubs, and logistical depots provided cadets with insights into how commanders addressed the challenges of moving troops and materiel across vast distances. For example, maps from the North African campaign illustrated how the Allies overcame logistical difficulties to support their forces in a harsh desert environment, offering lessons in adaptability and resourcefulness.

Another critical aspect of using World War II maps at West Point was fostering an appreciation for the role of intelligence and reconnaissance. Many operational maps included information gathered from aerial photography, captured enemy documents, and reports from reconnaissance units. Cadets learned how commanders used this intelligence to make informed decisions, predict enemy movements, and identify vulnerabilities. By studying maps of campaigns such as the D-Day invasion, cadets gained an understanding of how intelligence shaped operational planning and execution, from identifying landing sites to neutralizing key enemy positions.

The maps also facilitated wargaming exercises, where cadets were tasked with developing their own strategies based on historical scenarios. Using the maps as a foundation, cadets reenacted campaigns, assuming the roles of both Allied and Axis commanders. These exercises encouraged critical thinking, problem-solving, and an appreciation for the complexities of command. They also provided opportunities to test the principles of maneuver warfare, combined arms operations, and the integration of air and ground forces. By engaging with the maps in this way, cadets honed their ability to think like military leaders, preparing them for the challenges of real-world command.

In addition to their practical applications, the maps held symbolic significance, serving as tangible connections to the legacy of the "Greatest Generation." They reminded cadets of the sacrifices made by those who fought in World War II and underscored the responsibility of future officers to uphold the traditions of duty, honor, and country. The maps became tools for instilling a sense of historical continuity, encouraging cadets to view themselves as part of a long line of military leaders committed to defending the nation.

By 1953, the integration of World War II operational campaign maps into West Point’s curriculum represented a forward-thinking approach to military education. These maps bridged the gap between theory and practice, offering cadets a nuanced understanding of the art and science of warfare. They highlighted the enduring relevance of historical study in preparing for future conflicts, demonstrating that the lessons of the past could inform the strategies of tomorrow. Through the study of these maps, West Point not only honored the legacy of World War II but also ensured that its graduates were equipped to face the complexities of modern warfare with knowledge, skill, and confidence.

_____________________

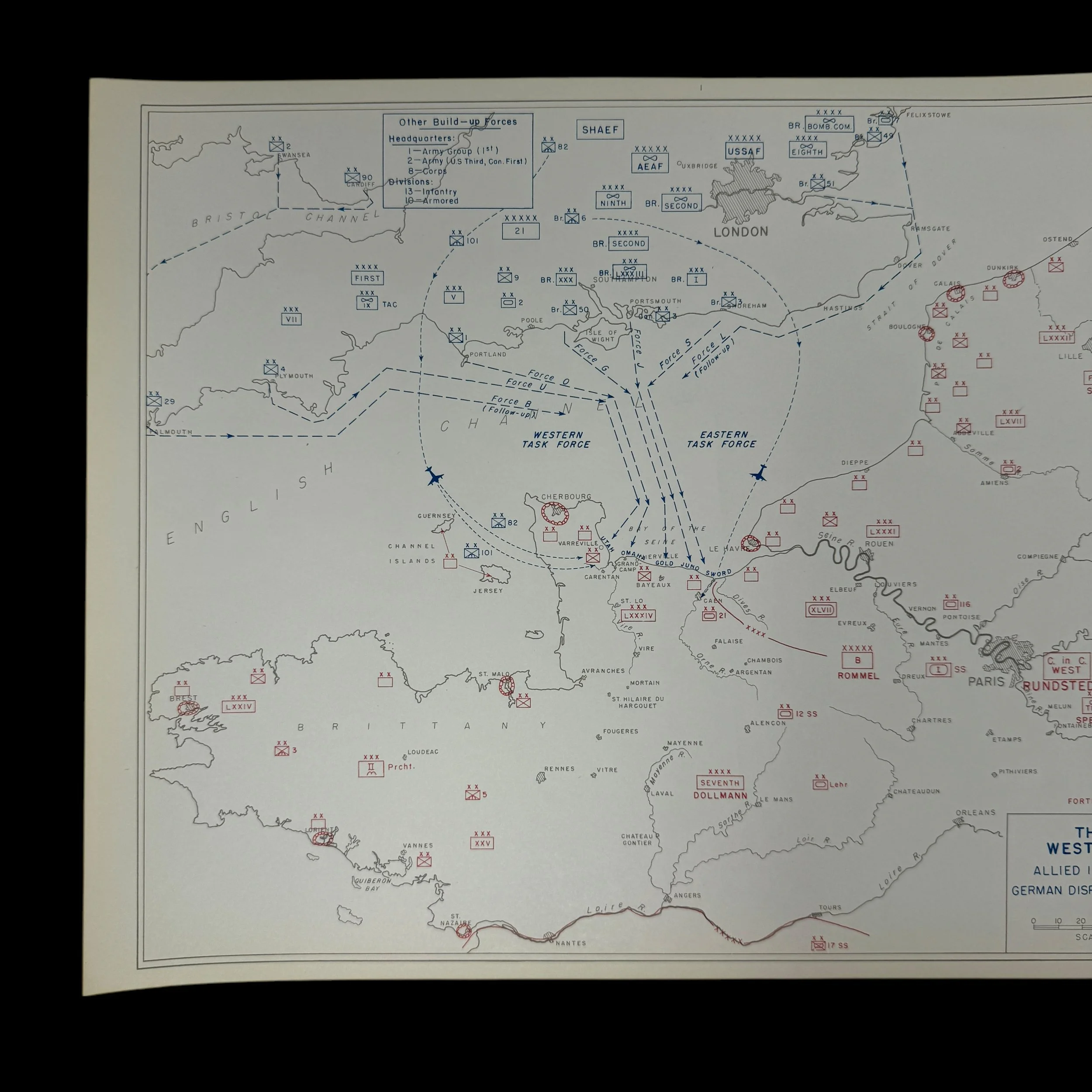

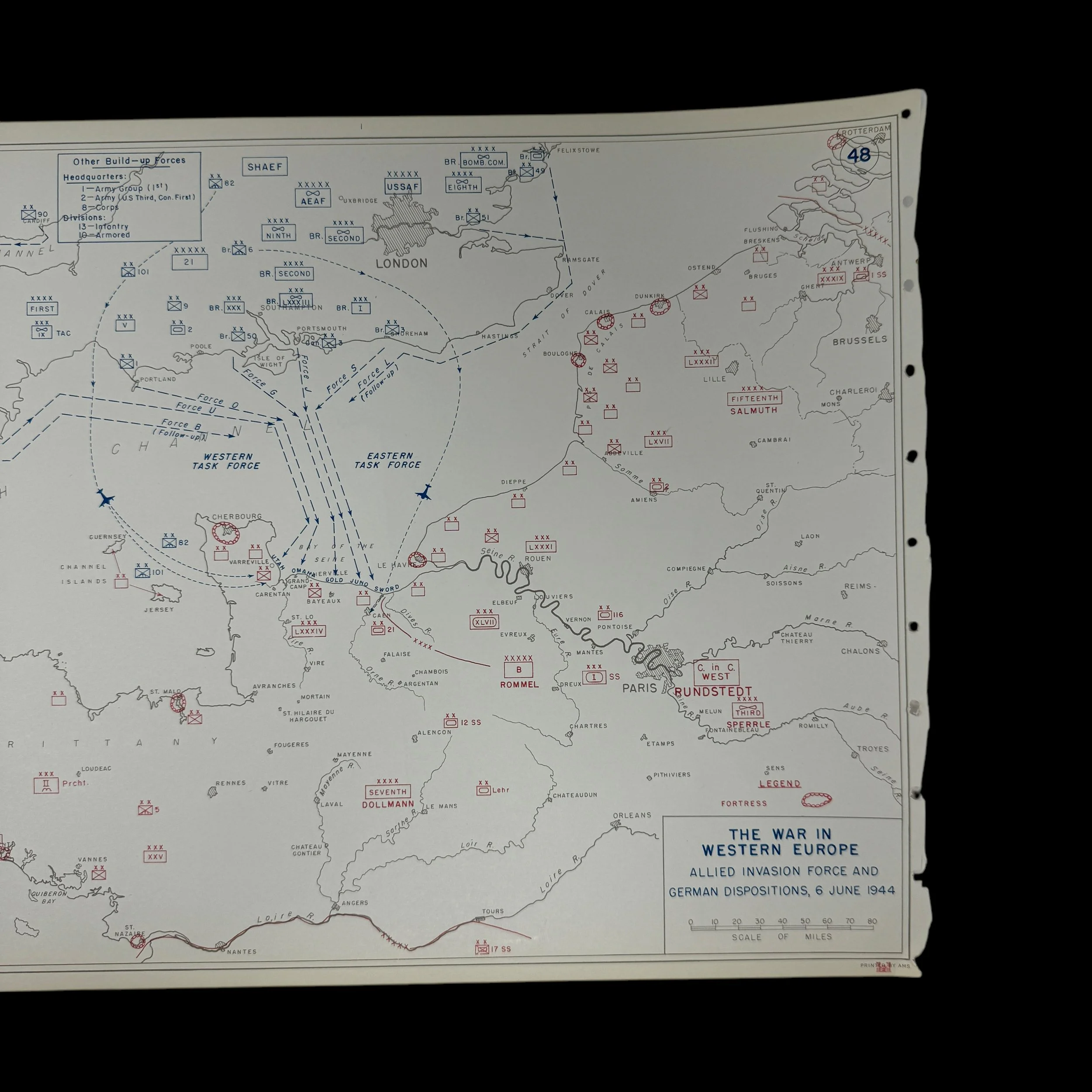

The Invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, remains one of the most complex and ambitious military operations in history. Codenamed Operation Overlord, the assault on Nazi-occupied France represented a pivotal moment in World War II, marking the beginning of the Allied liberation of Western Europe. The success of the operation depended on meticulous planning, the coordination of a vast Allied invasion force, and overcoming formidable German defensive positions. This essay examines the composition and roles of the Allied invasion force, as well as the German dispositions on D-Day, providing insight into the scale, strategy, and challenges of this monumental event.

The Allied Invasion Force

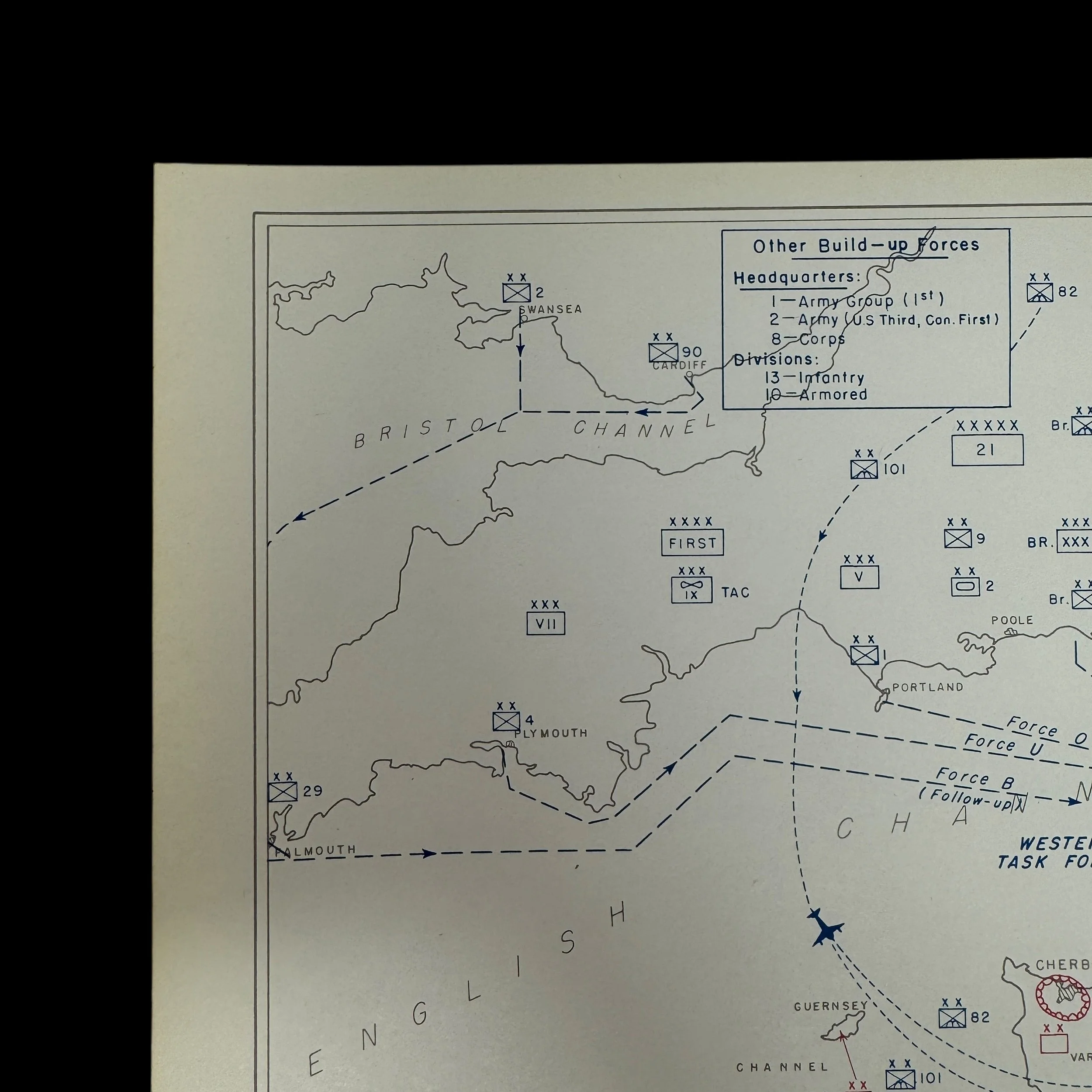

The Allied invasion force for D-Day was a coalition effort involving forces from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and other Allied nations, including Australia, New Zealand, Poland, Norway, and France. It was a massive undertaking that involved land, air, and naval forces working in unison to achieve a common objective: establish a foothold in Normandy and break through the Atlantic Wall, Germany's coastal defensive network.

Planning and Leadership

The invasion was spearheaded by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, with key contributions from British General Bernard Montgomery, who commanded the ground forces during the initial stages of the invasion. Planning for Operation Overlord began in earnest in 1943, with extensive efforts devoted to gathering intelligence, training troops, and coordinating logistics. A significant element of the plan was the deception operation known as Operation Fortitude, which misled the Germans into believing that the main invasion would occur at the Pas de Calais, drawing their forces away from Normandy.

Naval Forces

The naval component of the invasion, known as Operation Neptune, was one of the largest armadas ever assembled, comprising over 5,000 ships. This fleet included battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and landing craft, which transported the troops and provided artillery support during the landings. Naval bombardments played a critical role in neutralizing German coastal defenses, clearing the way for the landing forces.

Air Forces

Allied air forces conducted extensive operations leading up to and during D-Day. Over 13,000 aircraft, including bombers, fighters, and transport planes, were involved in the invasion. These aircraft carried out bombing missions to destroy German fortifications and disrupt their supply lines, provided air cover for the naval and ground forces, and deployed paratroopers behind enemy lines. Airborne divisions, such as the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and the British 6th Airborne Division, were critical in securing key objectives and disrupting German reinforcements.

Ground Forces

The land invasion involved over 156,000 troops, divided among five landing beaches, each assigned to specific Allied nations:

Utah Beach (U.S.): The westernmost beach, where American forces landed relatively unopposed and made swift progress inland.

Omaha Beach (U.S.): The most heavily defended and bloodiest landing site, where American troops faced fierce German resistance but ultimately secured the beachhead.

Gold Beach (British): Captured by the British 50th Infantry Division, who advanced inland to secure key objectives.

Juno Beach (Canadian): Assaulted by the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, who achieved significant progress despite facing tough defenses.

Sword Beach (British): The easternmost beach, where British forces aimed to link up with paratroopers securing bridges over the Orne River.

Each landing force faced unique challenges, ranging from strong coastal fortifications to heavy machine-gun fire and natural obstacles such as tidal conditions and minefields. Despite these difficulties, the Allies succeeded in securing all five beaches by the end of D-Day.

German Dispositions on June 6, 1944

The German defensive strategy along the Atlantic Wall was directed by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who had been tasked with preparing for an Allied invasion. Rommel recognized the importance of stopping the invasion at the beaches and worked to fortify coastal defenses. However, several factors, including resource constraints and strategic miscalculations, hindered the Germans’ ability to repel the Allied assault effectively.

The Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall was a series of fortifications that stretched along the western coast of Europe, from Norway to Spain. In Normandy, these defenses included concrete bunkers, machine-gun nests, anti-tank obstacles, barbed wire, and minefields. Coastal artillery batteries were positioned to target landing craft and ships offshore.

Rommel sought to strengthen the Atlantic Wall by increasing the number of obstacles and fortifications on the beaches and deploying more troops along the coastline. However, these efforts were incomplete by the time of the invasion, and many sections of the wall were inadequately manned or fortified.

German Command and Forces

The German command structure in Normandy was divided and inefficient, contributing to their inability to respond effectively to the invasion. The region fell under the overall command of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the Oberbefehlshaber West (Commander-in-Chief West), but Rommel had operational control of the defenses. Disagreements between the two commanders over strategy led to confusion and delays.

On D-Day, the German forces in Normandy were a mix of experienced troops and less capable units. Key elements included:

Static Infantry Divisions: Positioned along the coast, these units were composed of older soldiers, conscripts, and foreign volunteers. While they manned the fortifications, they lacked mobility and heavy firepower.

Panzer Divisions: Germany’s armored divisions were critical to counterattacking the Allies. However, many of these units were held in reserve and could not be deployed without Hitler’s explicit authorization, which delayed their response.

Elite Units: Certain sectors, such as Omaha Beach, were defended by experienced German troops, including elements of the 352nd Infantry Division, who inflicted heavy casualties on the Americans.

German Deception and Reaction

The Germans were deceived by Allied intelligence efforts, including the fictitious First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) under General George Patton, which convinced them that the main invasion would occur at the Pas de Calais. This deception caused the Germans to retain significant forces in the region, leaving Normandy less heavily defended than it might otherwise have been.

When the invasion began, German commanders were initially uncertain whether it was the main assault or a diversion. This hesitation, combined with Allied air and naval superiority, prevented an effective German response. Reinforcements, including Panzer divisions, were delayed due to disrupted communication lines and the confusion caused by airborne operations behind German lines.

The Clash on June 6, 1944

The landings on June 6 were met with varying degrees of resistance, depending on the strength of German defenses and the terrain. At Omaha Beach, for instance, the 352nd Infantry Division inflicted devastating casualties on the Americans, who faced a grueling battle to gain a foothold. Conversely, at Utah Beach, the weaker German defenses allowed American forces to advance with relatively low casualties.

German coastal artillery and machine-gun positions inflicted significant damage on Allied landing craft and infantry. However, the combination of overwhelming Allied airpower, naval bombardments, and the determination of the invading troops gradually overcame these defenses. By the end of the day, all five beaches were secured, though at great cost.