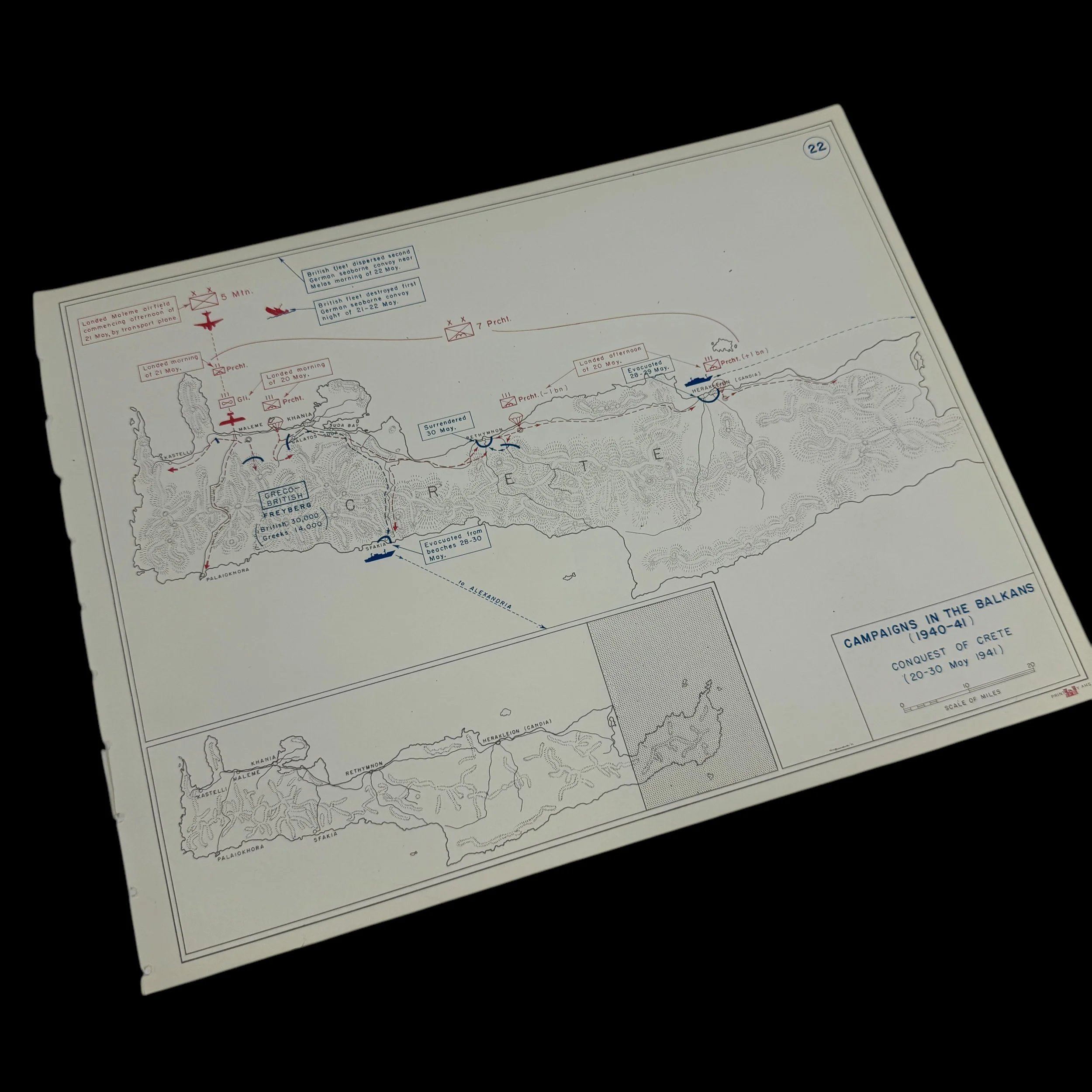

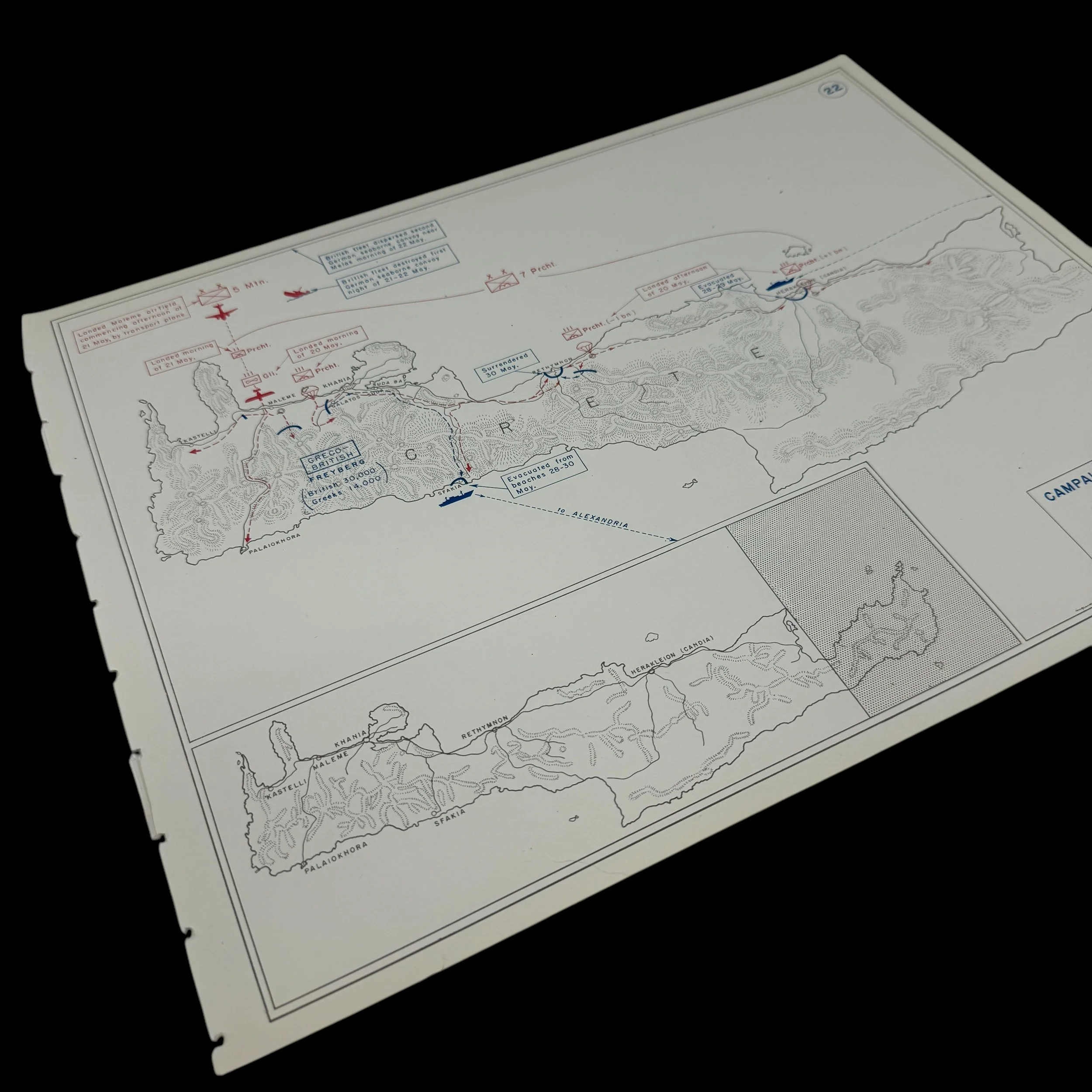

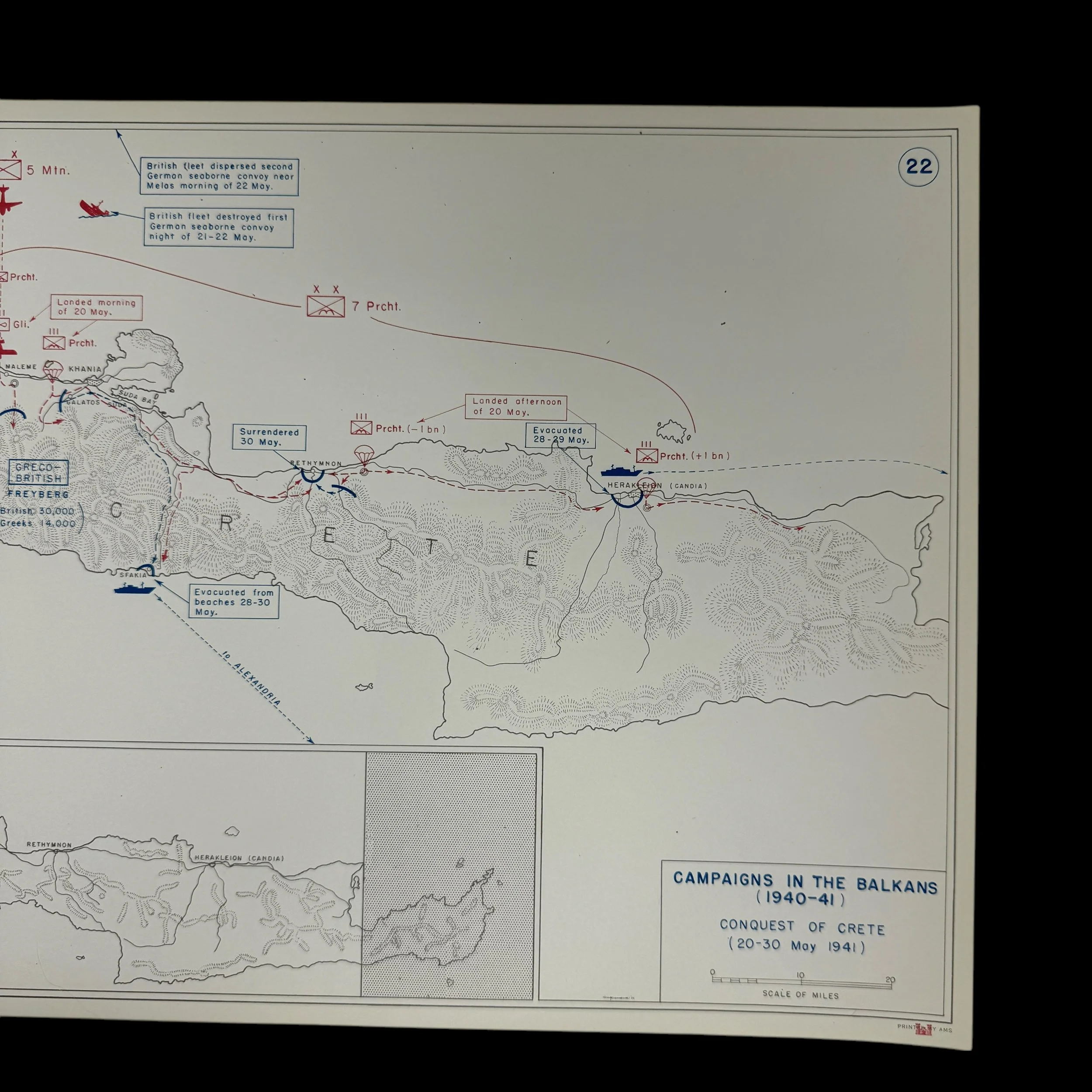

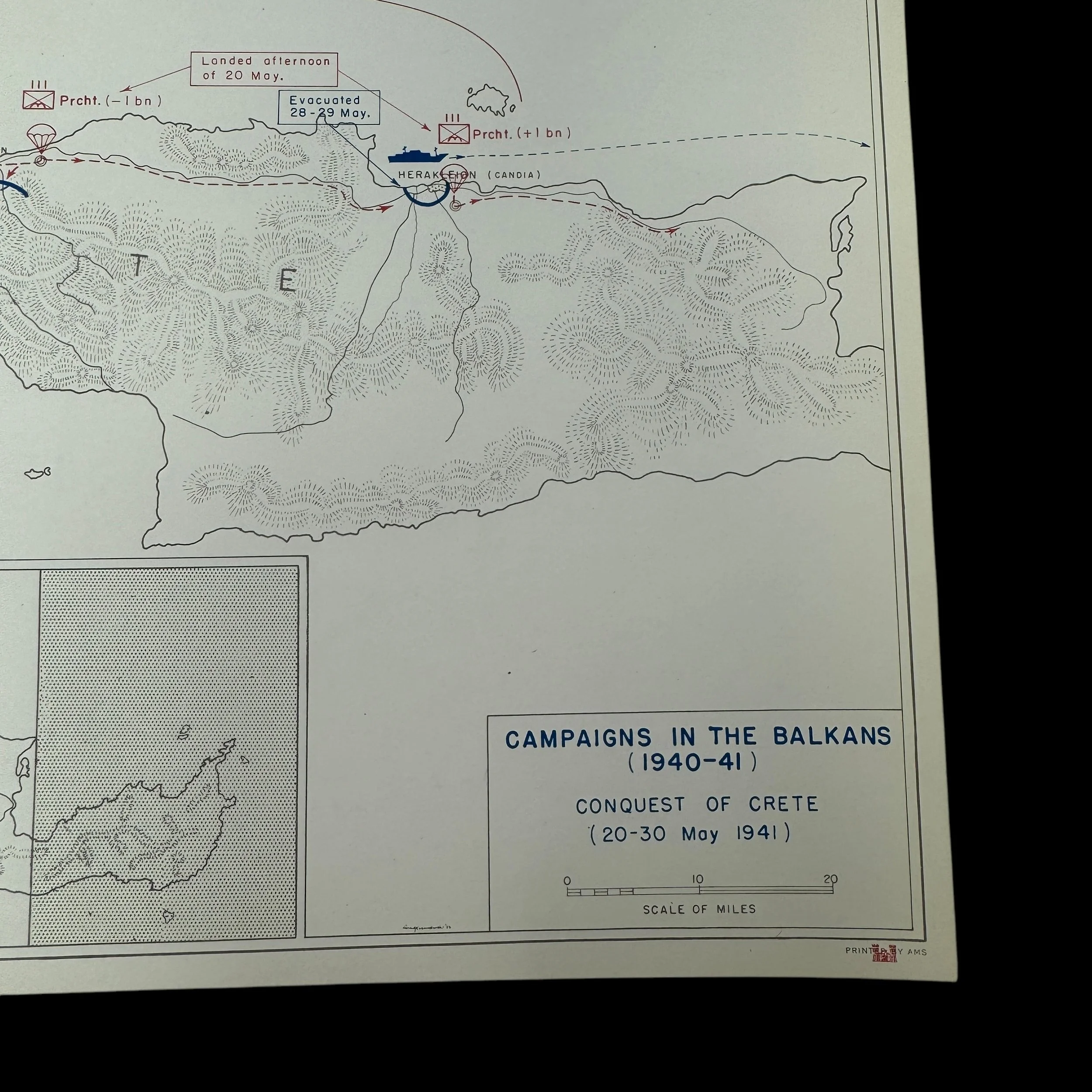

Original 1953 United States Military Academy West Point World War II Military Campaign Operational Study Map Plate (Balkans Campaign Conquest of Crete 1941)

Original 1953 United States Military Academy West Point World War II Military Campaign Operational Study Map Plate (Balkans Campaign Conquest of Crete 1941)

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A. and a full historical write-up

Type: Original 1953 United States Military Academy West Point World War II Military Campaign Operational Study Map Plate

Produced: Special map plate made by the Department of Military Art and Engineering (United States Military Academy - West Point)

Campaign: Balkans

Battle/Operation: Conquest of Crete 1941

Size: 14 × 10.5 inches

In the years following World War II, the United States Military Academy at West Point faced the monumental task of preparing future military leaders for an era of evolving warfare. By 1953, the Academy had integrated World War II operational campaign military maps into its curriculum as vital tools for studying the strategies and tactics employed during the conflict. These maps, which had served as critical planning and operational resources during the war, became essential teaching aids, allowing cadets to analyze real-world applications of military theory, refine their strategic thinking, and adapt lessons from the past to modern military challenges. The decision to incorporate these maps into training programs reflected the Academy's commitment to learning from history and enhancing the intellectual rigor of its officer education.

During World War II, operational campaign maps were indispensable to the planning and execution of military strategies. These maps were meticulously crafted, often combining topographical details, troop movements, supply routes, and key infrastructure information. Commanders relied on them to visualize battlefields, anticipate enemy actions, and coordinate large-scale operations across diverse terrains. Maps such as those used in the Normandy landings, the Battle of the Bulge, and the Pacific theater illustrated the complexity and dynamism of modern warfare. By 1953, these maps had become artifacts of historical and educational significance, offering a window into the decision-making processes of the war’s most pivotal moments.

At West Point, these maps were used to teach cadets about operational planning, logistical coordination, and the execution of combined arms strategies. Instructors often began by presenting maps from campaigns such as Operation Overlord or the Battle of Midway, highlighting the strategic considerations that shaped these operations. For example, the intricate plans for the Normandy invasion, which involved coordinating naval, air, and ground forces, demonstrated the importance of synchronization in multi-domain warfare. Cadets analyzed how Allied commanders used maps to identify key objectives, such as securing beaches, establishing supply lines, and advancing inland, all while countering German defenses along the Atlantic Wall.

One of the primary ways these maps were utilized was through the study of operational art—a concept that bridges the gap between strategy and tactics. Operational art involves the design and execution of campaigns to achieve strategic goals within the constraints of time, space, and resources. World War II operational maps provided cadets with concrete examples of this concept in action. By examining the geographical constraints, enemy dispositions, and logistical challenges depicted on these maps, cadets could assess how commanders made decisions to achieve their objectives while minimizing risks and exploiting opportunities.

Moreover, the maps served as case studies for analyzing the successes and failures of wartime operations. For instance, cadets studying the Battle of the Bulge examined maps that detailed German troop movements, the positioning of Allied forces, and the topographical challenges of the Ardennes Forest. This analysis helped them understand how Allied commanders responded to the surprise offensive and ultimately turned the tide in their favor. Similarly, maps from the Pacific theater, such as those depicting the island-hopping campaign, illustrated the strategic importance of selecting objectives that balanced the need for progress with the necessity of conserving resources and minimizing casualties.

Instructors at West Point also used these maps to emphasize the importance of logistics in modern warfare. World War II had demonstrated that the ability to sustain armies through effective supply chain management was as crucial as battlefield tactics. Maps showing supply routes, transportation hubs, and logistical depots provided cadets with insights into how commanders addressed the challenges of moving troops and materiel across vast distances. For example, maps from the North African campaign illustrated how the Allies overcame logistical difficulties to support their forces in a harsh desert environment, offering lessons in adaptability and resourcefulness.

Another critical aspect of using World War II maps at West Point was fostering an appreciation for the role of intelligence and reconnaissance. Many operational maps included information gathered from aerial photography, captured enemy documents, and reports from reconnaissance units. Cadets learned how commanders used this intelligence to make informed decisions, predict enemy movements, and identify vulnerabilities. By studying maps of campaigns such as the D-Day invasion, cadets gained an understanding of how intelligence shaped operational planning and execution, from identifying landing sites to neutralizing key enemy positions.

The maps also facilitated wargaming exercises, where cadets were tasked with developing their own strategies based on historical scenarios. Using the maps as a foundation, cadets reenacted campaigns, assuming the roles of both Allied and Axis commanders. These exercises encouraged critical thinking, problem-solving, and an appreciation for the complexities of command. They also provided opportunities to test the principles of maneuver warfare, combined arms operations, and the integration of air and ground forces. By engaging with the maps in this way, cadets honed their ability to think like military leaders, preparing them for the challenges of real-world command.

In addition to their practical applications, the maps held symbolic significance, serving as tangible connections to the legacy of the "Greatest Generation." They reminded cadets of the sacrifices made by those who fought in World War II and underscored the responsibility of future officers to uphold the traditions of duty, honor, and country. The maps became tools for instilling a sense of historical continuity, encouraging cadets to view themselves as part of a long line of military leaders committed to defending the nation.

By 1953, the integration of World War II operational campaign maps into West Point’s curriculum represented a forward-thinking approach to military education. These maps bridged the gap between theory and practice, offering cadets a nuanced understanding of the art and science of warfare. They highlighted the enduring relevance of historical study in preparing for future conflicts, demonstrating that the lessons of the past could inform the strategies of tomorrow. Through the study of these maps, West Point not only honored the legacy of World War II but also ensured that its graduates were equipped to face the complexities of modern warfare with knowledge, skill, and confidence.

_____________________

The campaign in the Balkans from 1940 to 1941 was a pivotal series of military operations that demonstrated the strategic significance of the region in World War II. The campaign encompassed the invasion of Greece and Yugoslavia by Axis forces, followed by the German conquest of Crete. These operations underscored the importance of airpower, the vulnerabilities of overextended supply lines, and the complexity of waging war in challenging terrain. The conquest of Crete, in particular, was a groundbreaking campaign, marking the first large-scale airborne invasion in military history and leaving a lasting legacy on warfare.

The Context of the Balkan Campaign

By the late 1930s, the Balkans had become a focus of geopolitical competition between the Axis and Allied powers. The region’s strategic location, providing access to the Mediterranean and the Middle East, made it a valuable prize. Italy’s ambitions under Benito Mussolini led to the first major act of aggression in the Balkans when Italy invaded Greece in October 1940. However, the poorly planned and executed campaign faltered against determined Greek resistance, forcing Mussolini to call for German assistance.

Germany, under Adolf Hitler, viewed the Balkans as a critical region for securing its southern flank ahead of Operation Barbarossa, the planned invasion of the Soviet Union. Hitler was also concerned about the increasing British presence in Greece, which threatened Axis control of the Mediterranean. These factors led to the German decision to intervene in the Balkans, launching invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece in April 1941.

The Invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece

The German offensive against Yugoslavia began on April 6, 1941, with a swift and overwhelming assault. Utilizing blitzkrieg tactics, German forces rapidly advanced through the country, exploiting its political instability and weak defenses. Yugoslavia, which had recently undergone a coup that replaced its pro-Axis government with one sympathetic to the Allies, was unprepared for the scale of the attack. Within 11 days, Yugoslavia surrendered, effectively neutralizing the country as a military threat.

Simultaneously, Germany launched its invasion of Greece. Despite fierce resistance from Greek and British Commonwealth forces, the Germans quickly outflanked the Allied defenses by advancing through Yugoslavia into northern Greece. The Metaxas Line, Greece’s main defensive fortification, was bypassed, and the Germans captured Thessaloniki on April 9. By the end of April, Athens had fallen, and the remnants of Allied forces retreated to the island of Crete, setting the stage for the next phase of the campaign.

The Conquest of Crete: Operation Merkur

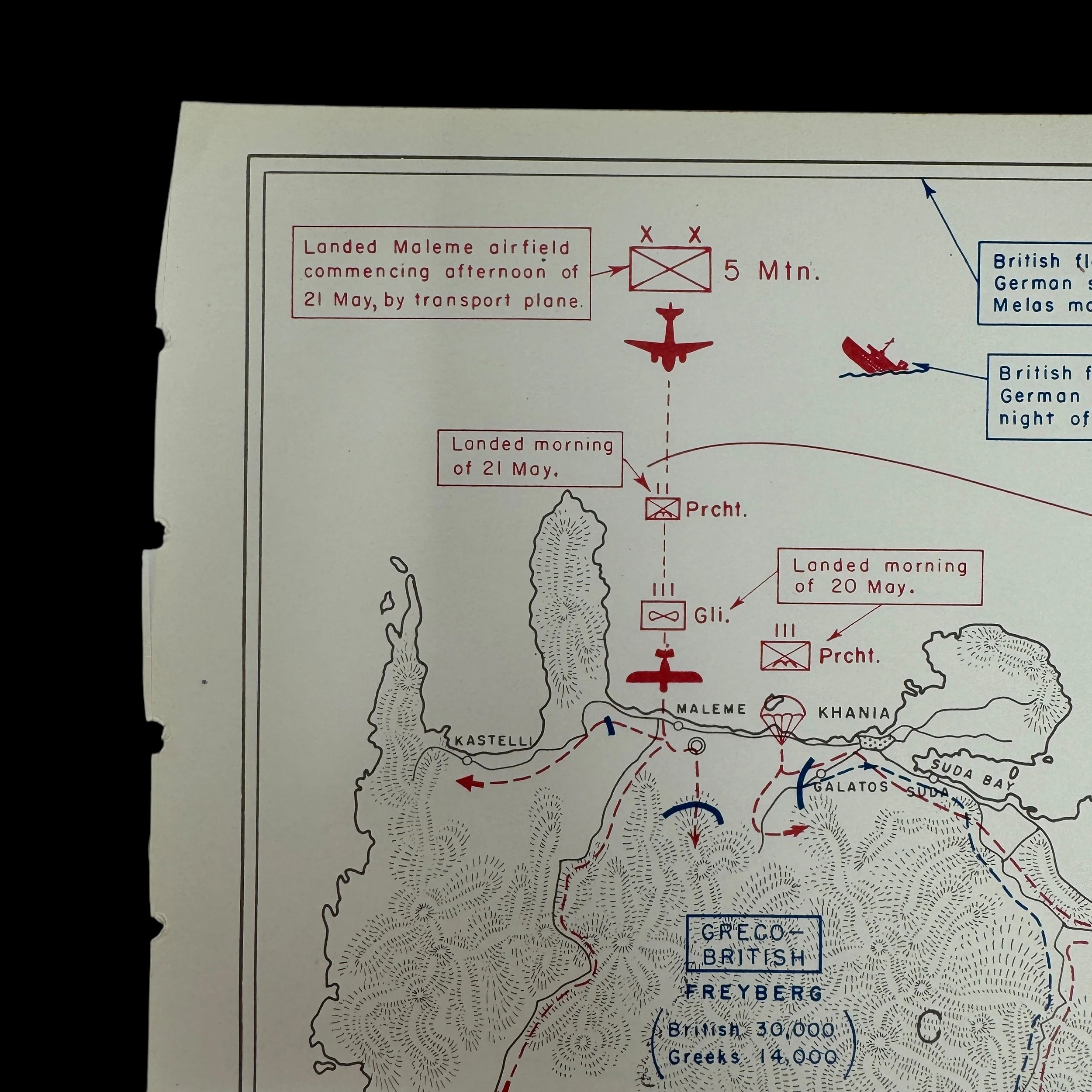

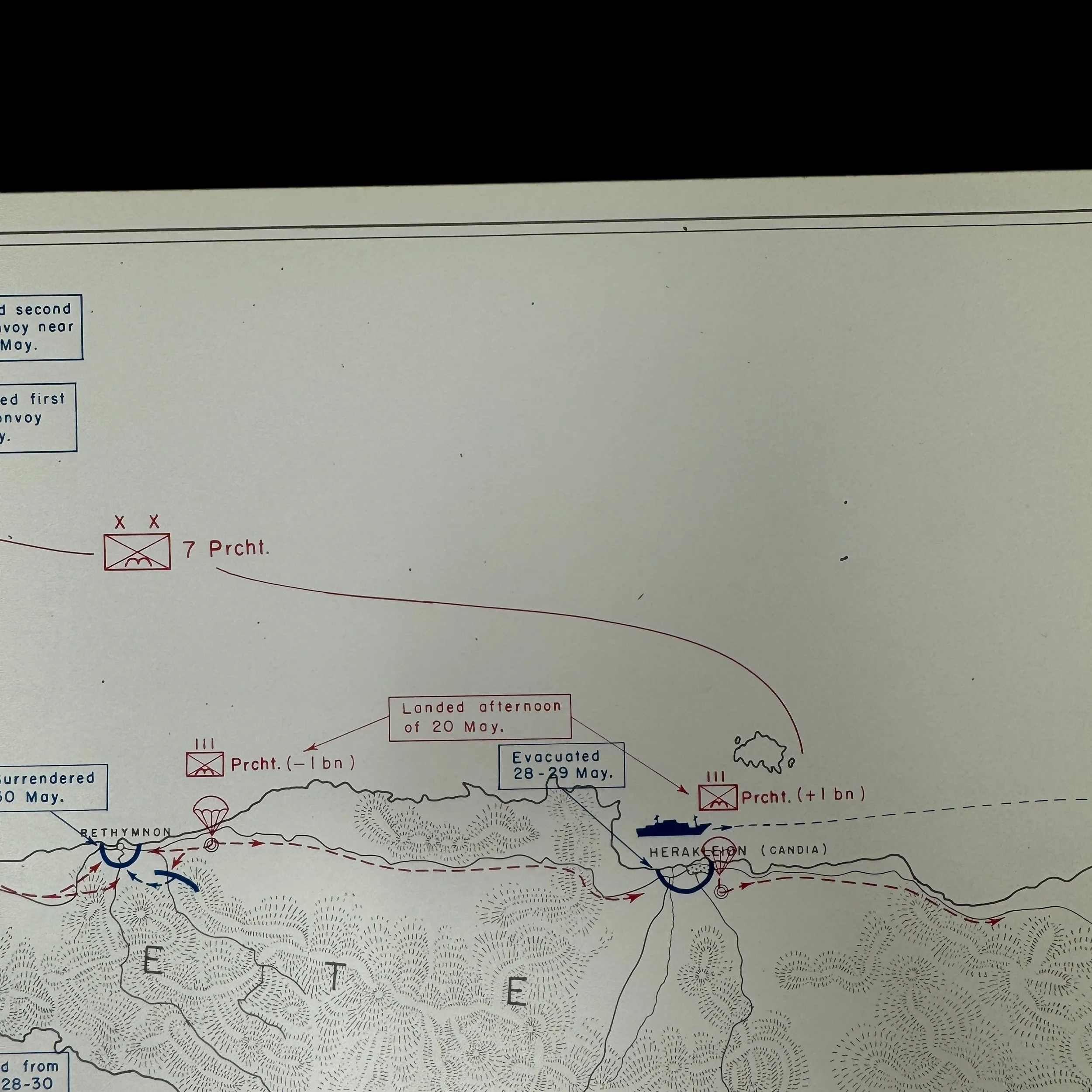

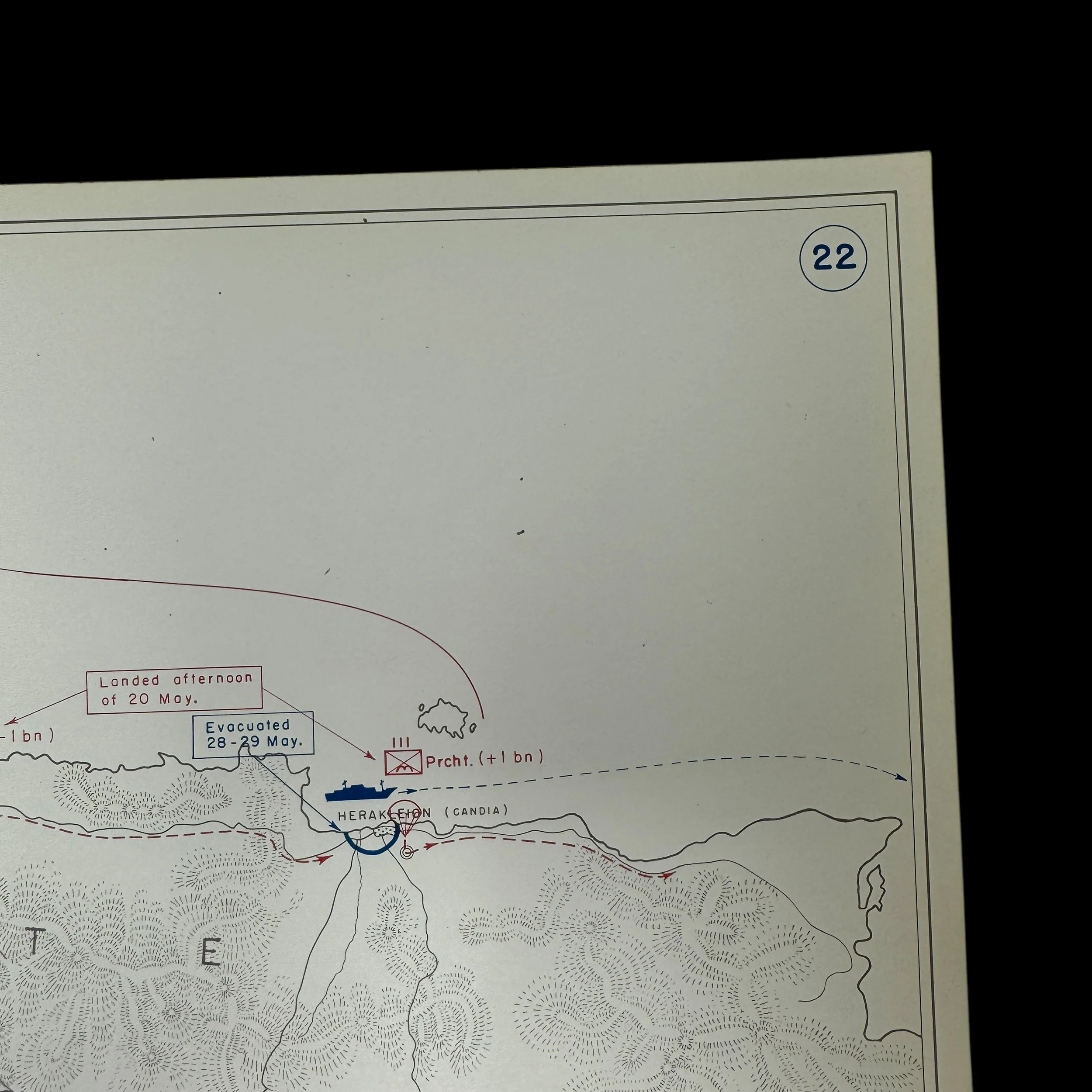

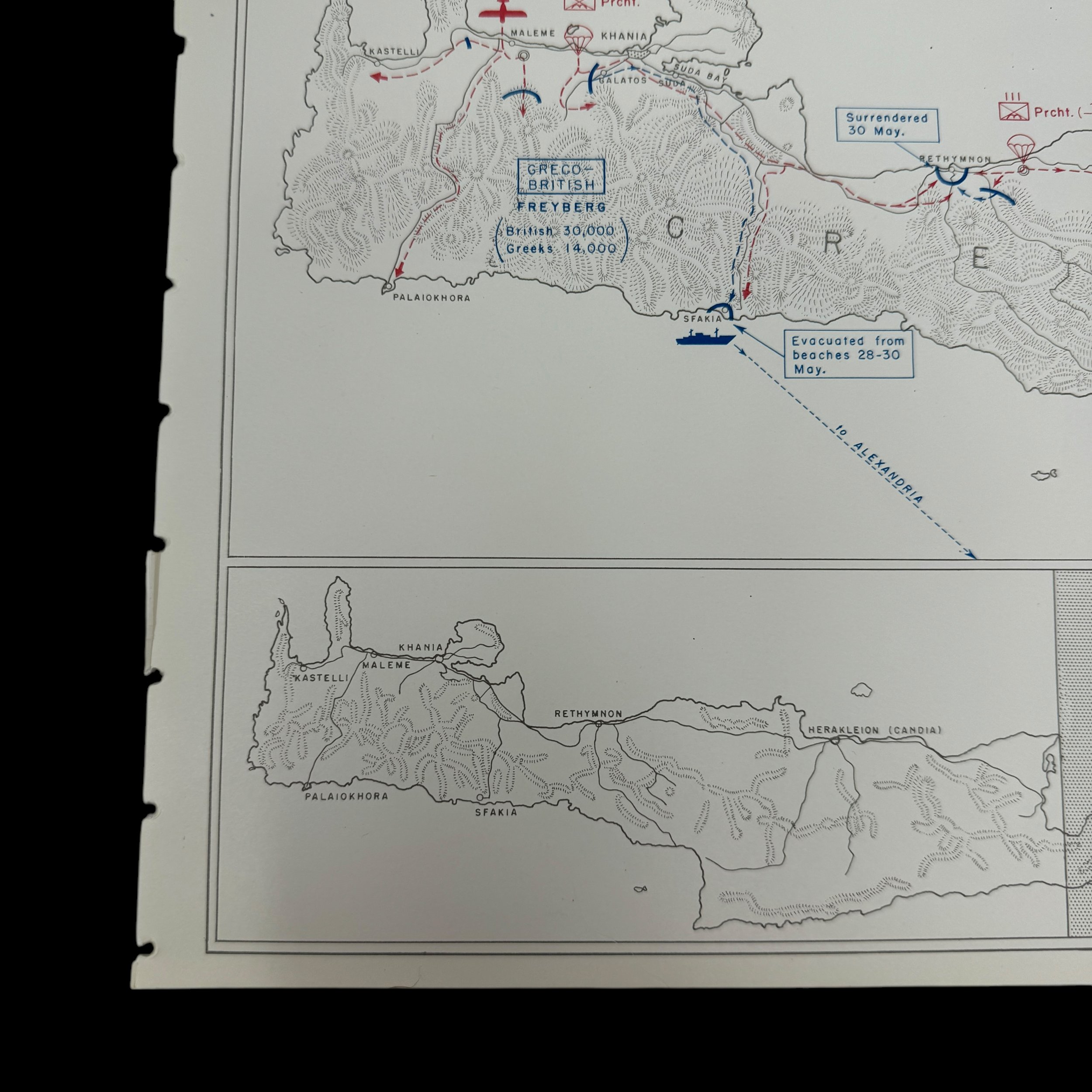

The conquest of Crete, known as Operation Merkur (Operation Mercury), began on May 20, 1941. The operation was unique in that it relied almost entirely on airborne forces for its initial assault. German paratroopers, or Fallschirmjäger, were tasked with seizing key objectives on the island, including airfields and ports, to pave the way for reinforcements.

The German plan involved simultaneous airborne landings at several locations: Maleme, Rethymno, Heraklion, and the area surrounding Chania. The operation was preceded by intense Luftwaffe bombing to weaken Allied defenses and disrupt communications. German intelligence underestimated the strength of the Allied forces on Crete, which consisted of British, Australian, New Zealand, and Greek troops, as well as local resistance fighters.

The Battle for Maleme Airfield

The battle for Maleme Airfield, located on the western part of the island, was the focal point of the German assault. Control of the airfield was critical for the success of the operation, as it would allow German reinforcements to arrive by air. Initially, the German paratroopers faced heavy resistance, suffering significant casualties as they landed under fire. Many Fallschirmjäger were killed before they could regroup, and their equipment, which was dropped separately, often fell into Allied hands.

However, a critical misjudgment by the Allied commanders shifted the course of the battle. Believing the airfield to be lost, Allied forces withdrew from Maleme on the night of May 20, allowing the Germans to secure the area. Once the airfield was in German hands, reinforcements, including additional paratroopers and mountain troops, began arriving, tipping the balance of the battle.

The Broader Campaign on Crete

While Maleme Airfield became the linchpin of the German operation, fierce fighting continued across the island. The Allied forces, though outnumbered and outgunned, mounted a determined defense, utilizing the rugged terrain to their advantage. The local Cretan population also played a significant role, engaging in guerrilla warfare against the German invaders. Armed with whatever weapons they could find, the Cretans inflicted casualties and disrupted German operations, demonstrating remarkable resilience.

Despite these efforts, the Germans gradually gained the upper hand. Their superiority in airpower allowed them to isolate and attack Allied positions, while the arrival of reinforcements from the mainland strengthened their ground forces. By June 1, 1941, the Allies were forced to evacuate the remaining troops from Crete, marking the end of organized resistance on the island.

The Aftermath of the Conquest of Crete

The conquest of Crete was a costly victory for Germany. The Fallschirmjäger suffered heavy casualties, with nearly 4,000 killed and thousands more wounded. The high losses led Hitler to conclude that large-scale airborne operations were too risky, and the German military shifted its focus away from such tactics for the remainder of the war. However, the operation demonstrated the potential of airborne forces when properly supported and highlighted the importance of airpower in modern warfare.

For the Allies, the defeat on Crete was a sobering reminder of the importance of air superiority and effective communication. The inability to coordinate their defense and the failure to hold key objectives like Maleme Airfield were critical factors in the outcome. Despite their defeat, the Allied forces on Crete inflicted significant losses on the Germans and demonstrated the value of determined resistance, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

The Cretan population paid a heavy price for their role in resisting the German invasion. The Germans responded with brutal reprisals, executing civilians and destroying villages suspected of aiding the resistance. This harsh treatment only strengthened the resolve of the Cretans, who continued to resist the occupation throughout the war.

The Strategic Significance of the Balkan Campaign

The Balkan campaign had far-reaching consequences for the course of World War II. For Germany, the campaign delayed the launch of Operation Barbarossa by several weeks, forcing them to divert resources and attention to the region. This delay has been the subject of historical debate, with some arguing that it contributed to Germany’s failure to achieve a decisive victory in the Soviet Union before the onset of winter.

The campaign also highlighted the limitations of Axis collaboration. Mussolini’s failure in Greece and the subsequent need for German intervention exposed the weaknesses of the Italian military and strained the German war effort. Meanwhile, the brutal occupation policies in the Balkans fueled resistance movements that tied down significant Axis resources throughout the war.

The campaign in the Balkans from 1940 to 1941, culminating in the conquest of Crete, was a complex and multifaceted operation that demonstrated the evolving nature of modern warfare. The use of airborne forces in the battle for Crete was a groundbreaking development, showcasing both the potential and the limitations of this new form of warfare. While the Germans achieved their objectives, the campaign came at a high cost and had significant strategic repercussions. For the Allies, the defeat on Crete underscored the importance of air superiority, effective coordination, and the role of local populations in resisting occupation. The lessons of the Balkan campaign would resonate throughout the remainder of the war, shaping military strategies and highlighting the enduring significance of the region in global conflicts.