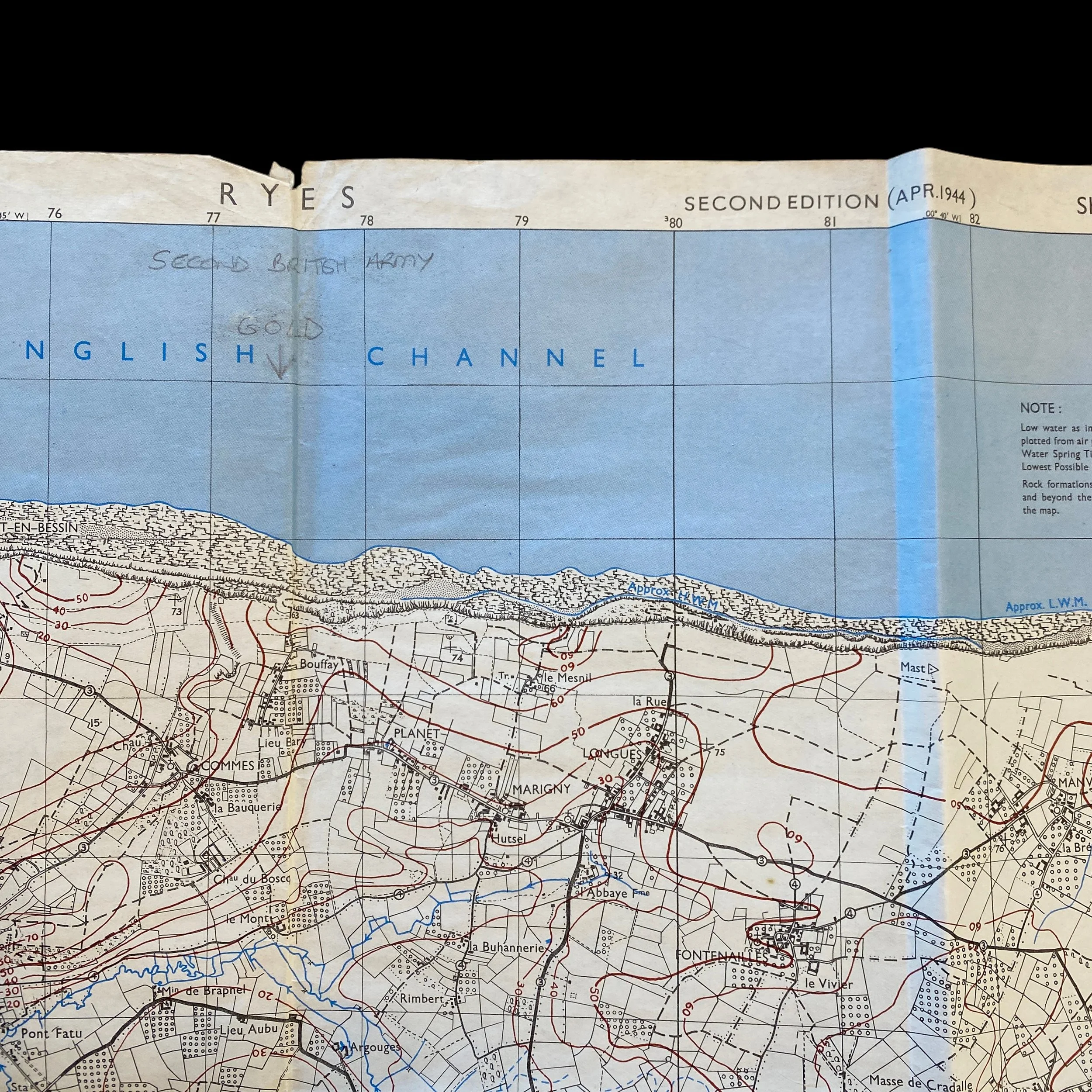

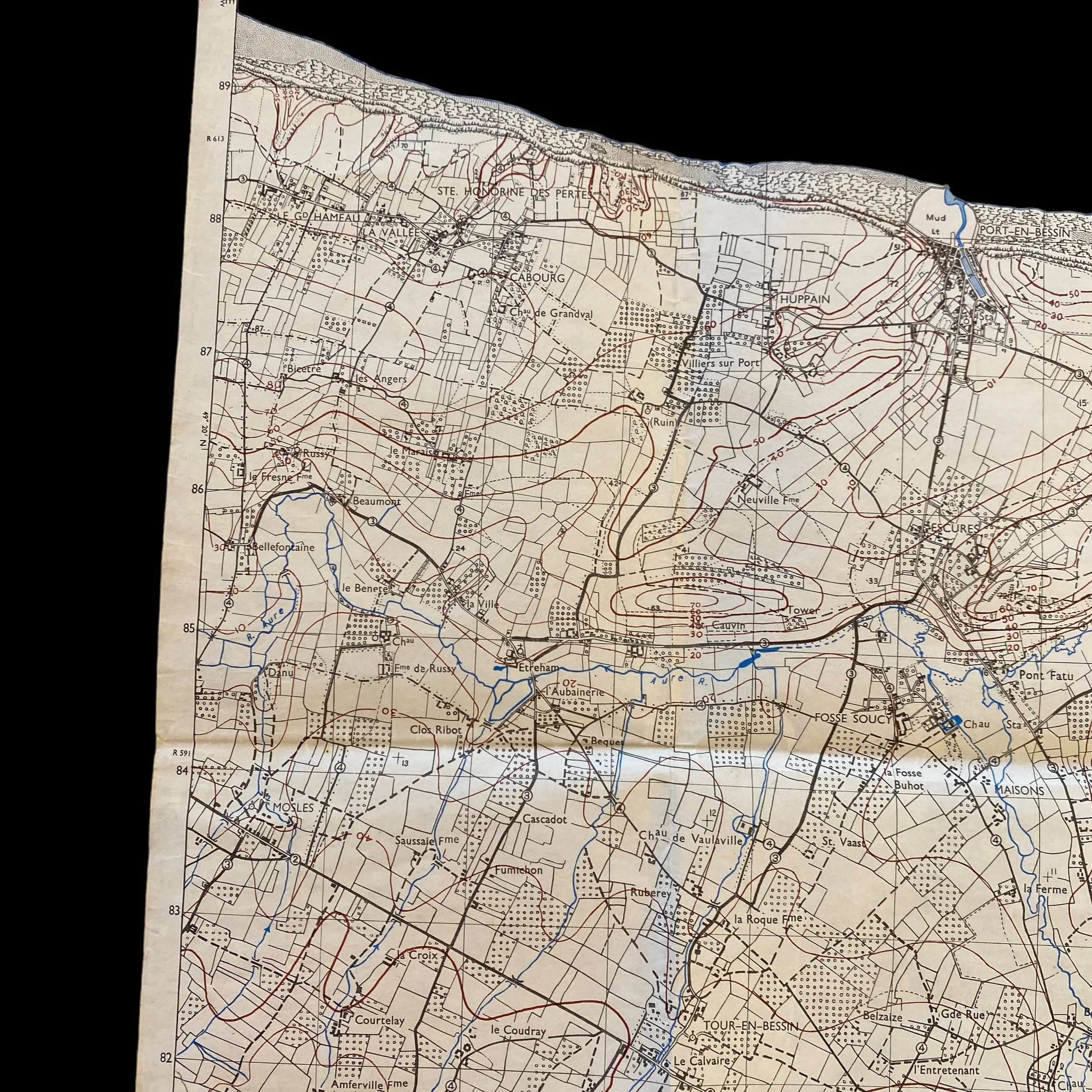

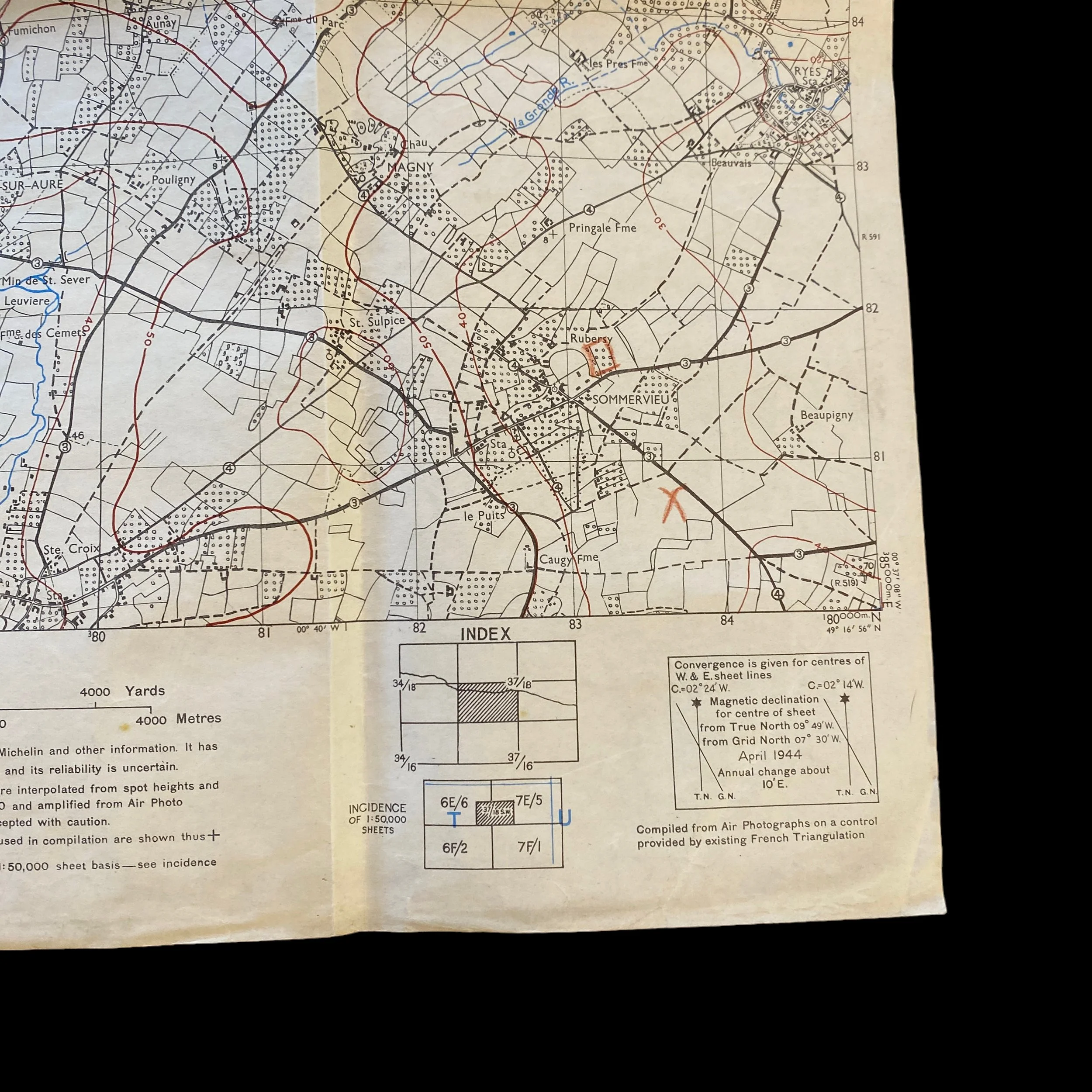

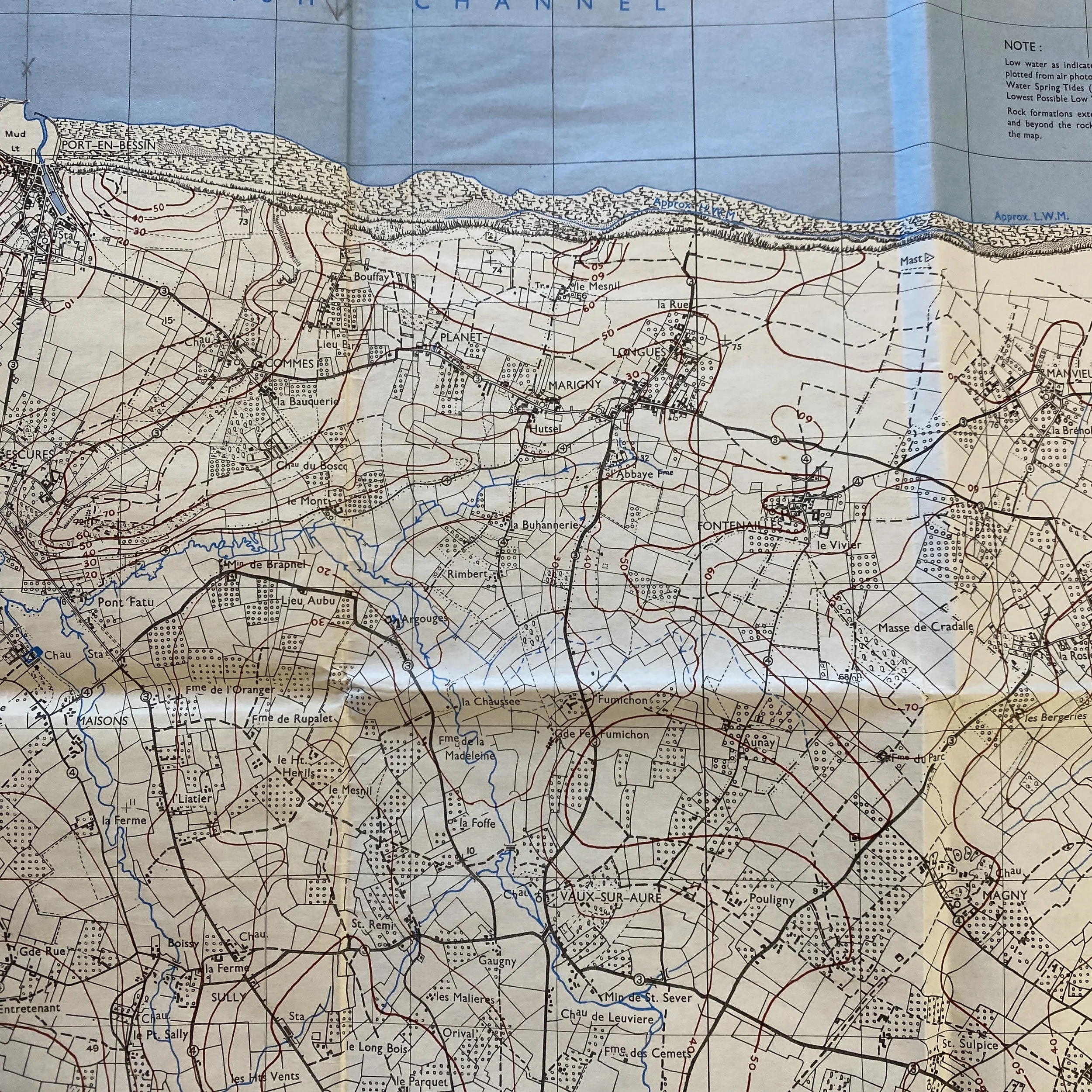

VERY RARE! WWII 1944 D-Day Omaha Beach (FOX GREEN) 1st Infantry Division Beachhead Combat Assault Map

VERY RARE! WWII 1944 D-Day Omaha Beach (FOX GREEN) 1st Infantry Division Beachhead Combat Assault Map

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

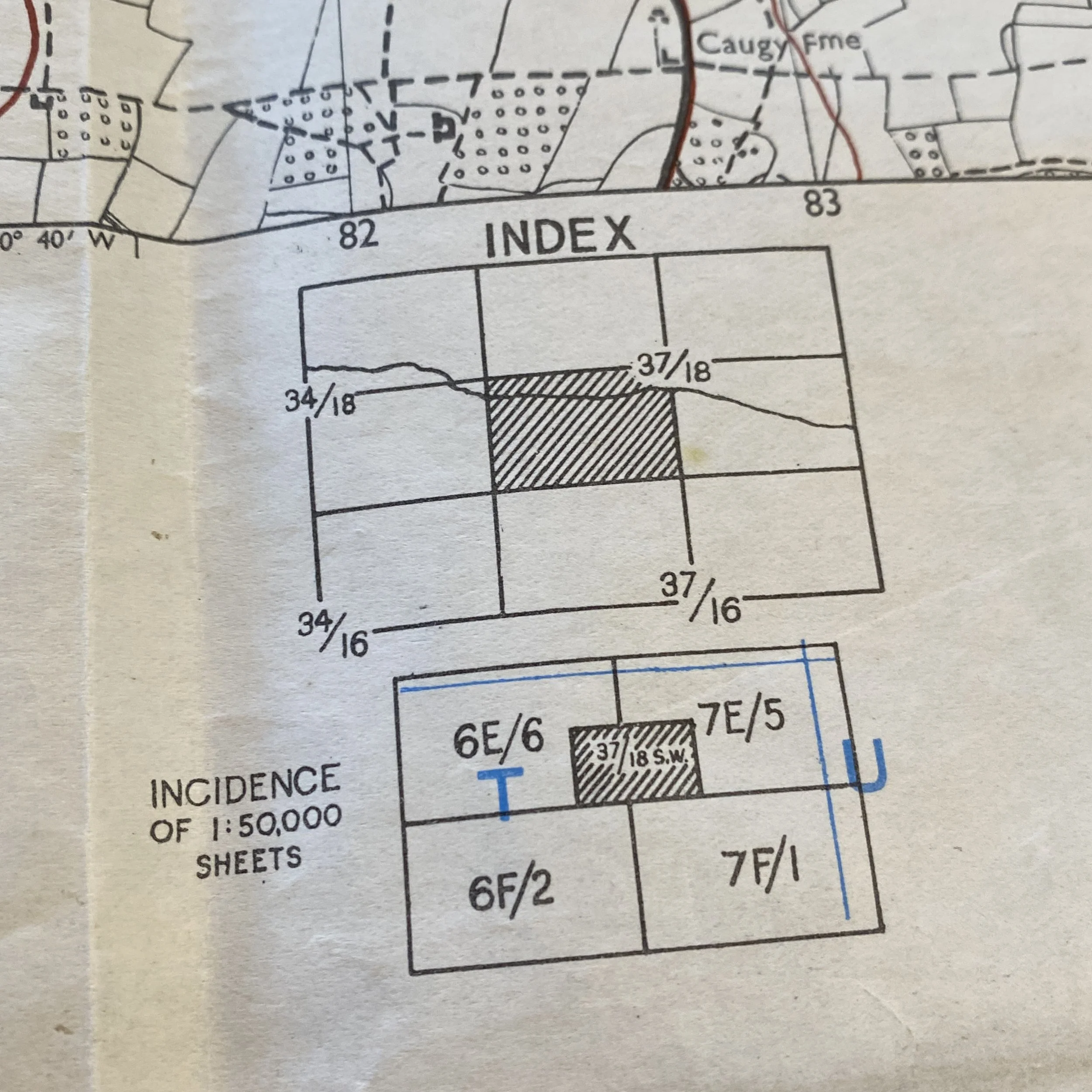

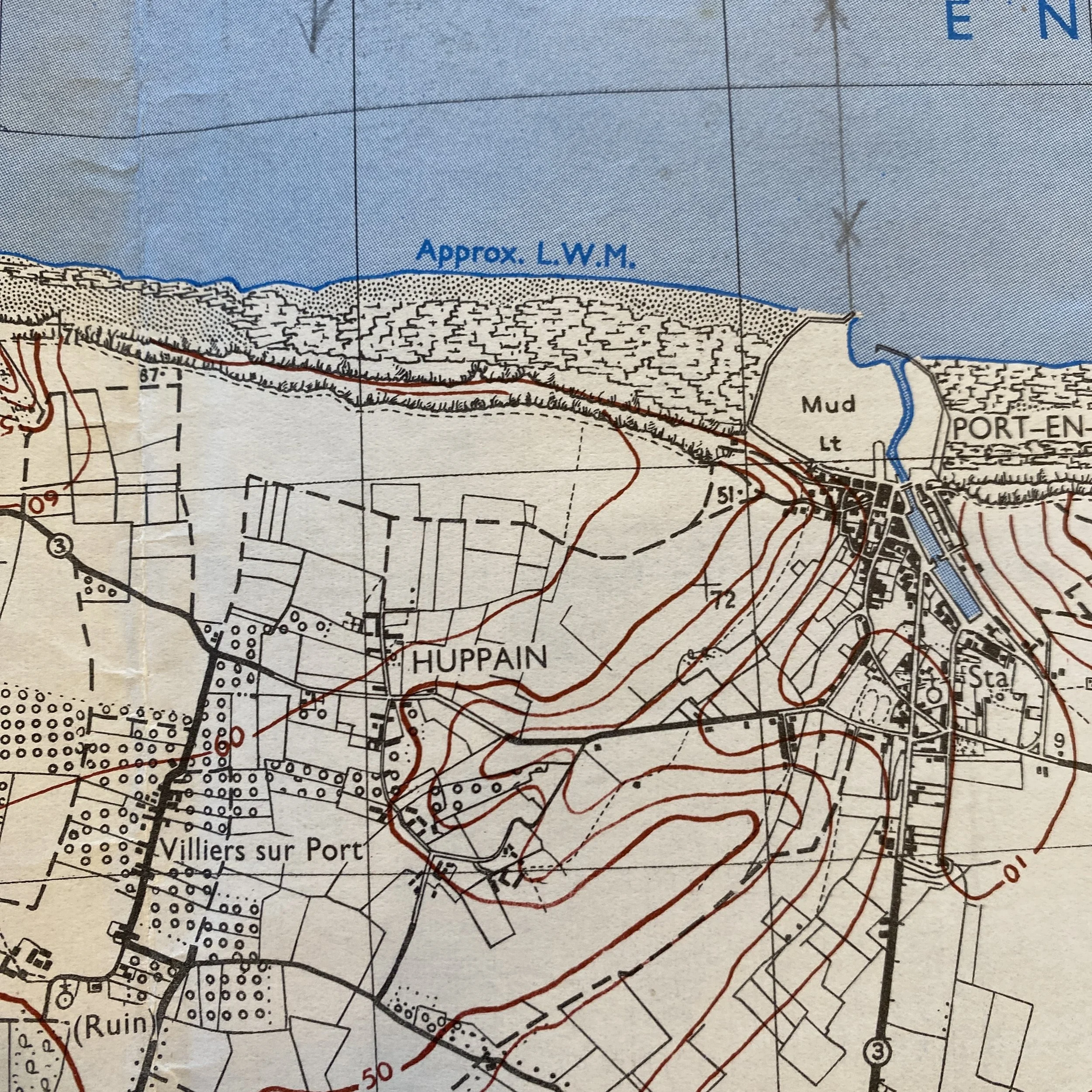

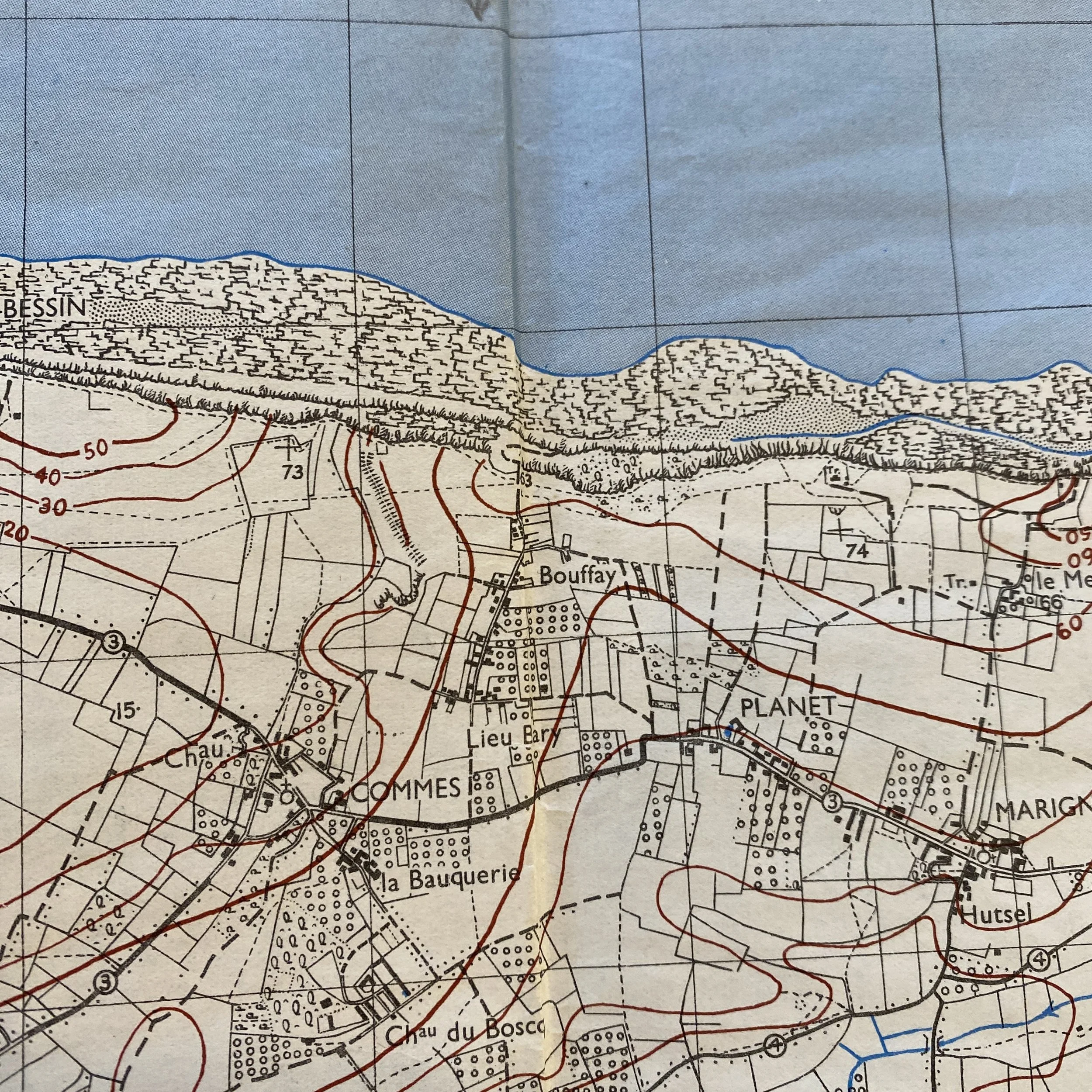

Similar to the BIGOT collection, only a small handful of this series of these D-Day combat assault maps exist. This is the exact map that was carried ashore by 1st Infantry Division soldiers landing on all sectors of Omaha Beach on June 6th, 1944.

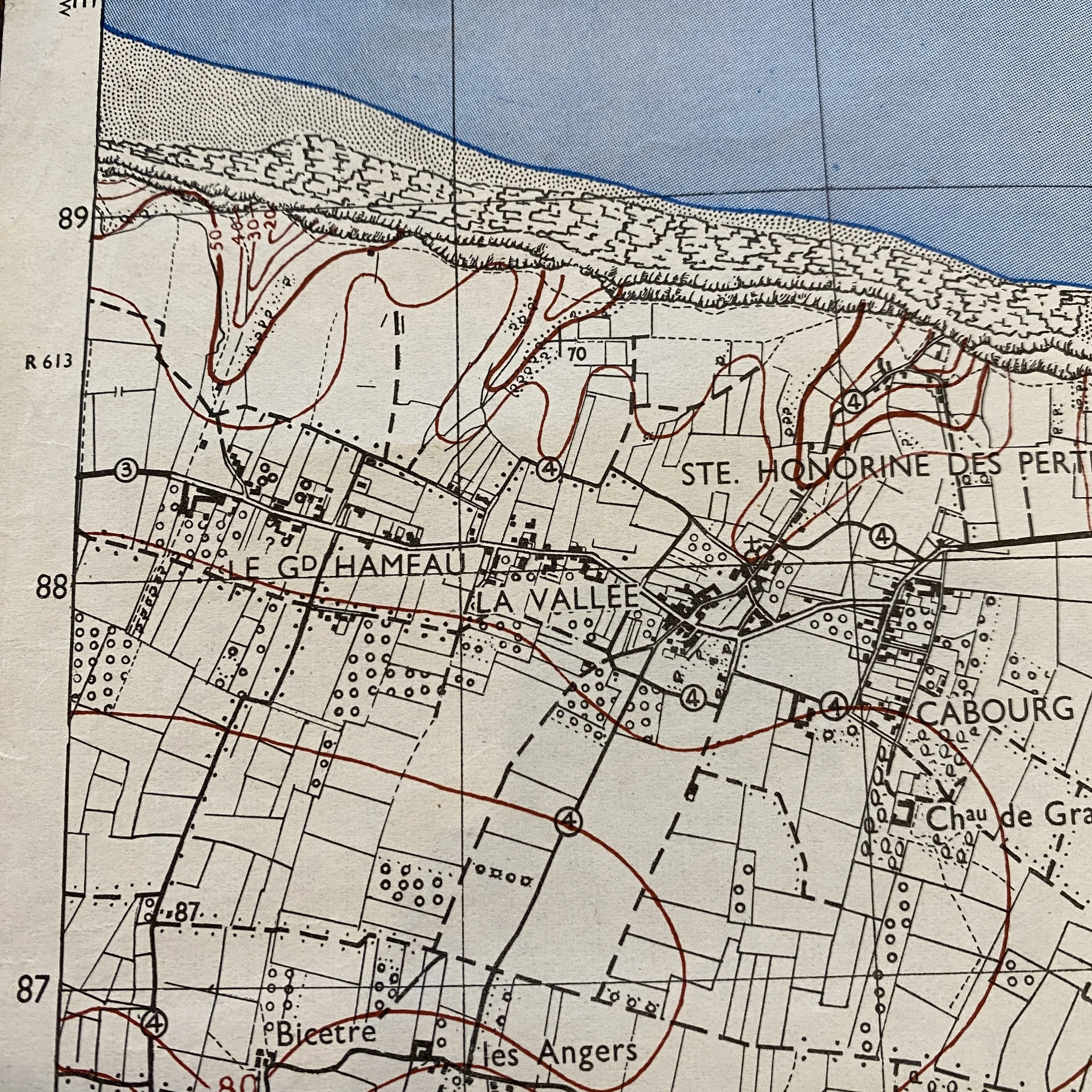

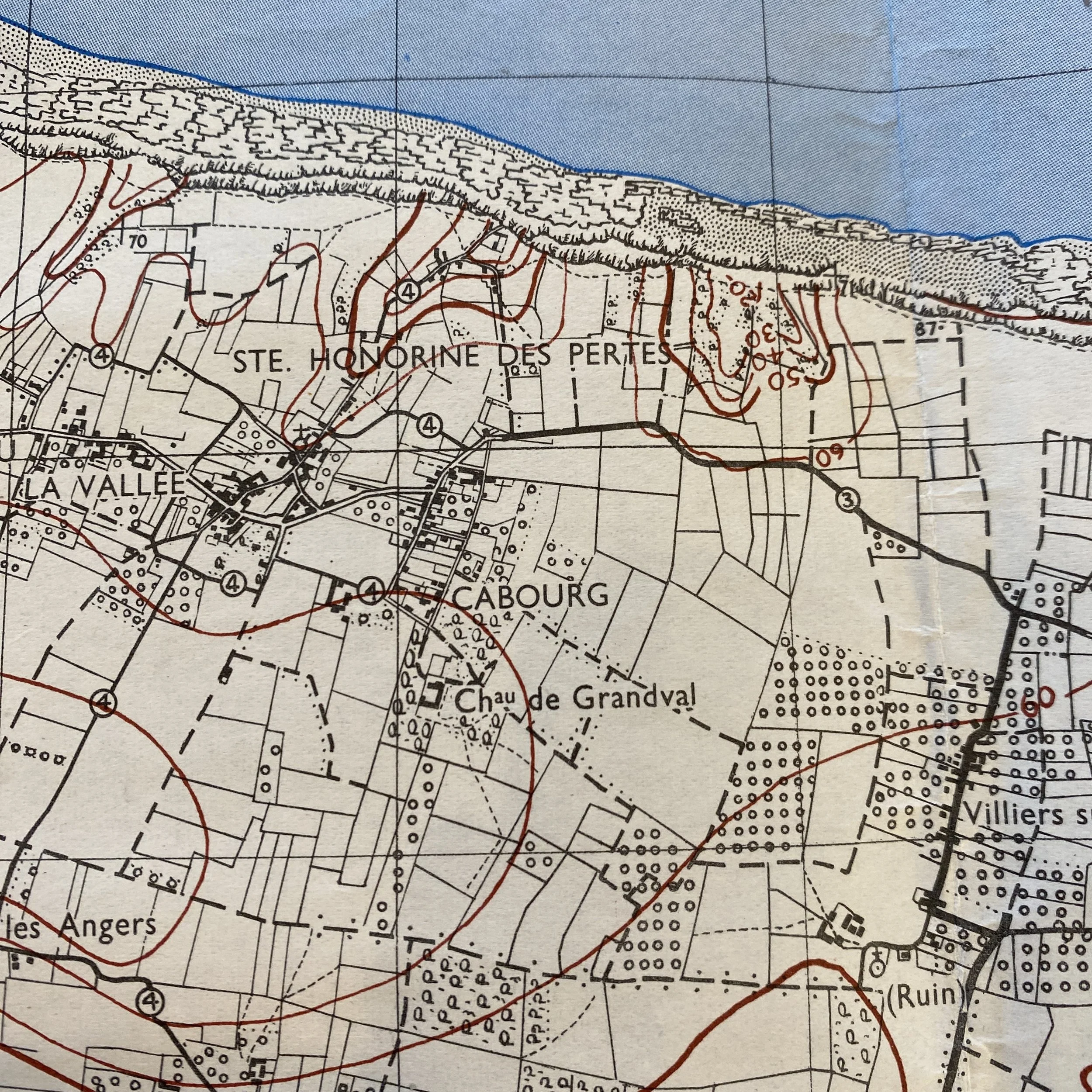

This extremely rare and museum-grade 1st Infantry Division “BIG RED ONE” WWII Operation Overlord Omaha Beach D-Day landing map was used on June 6th, 1944 as U.S. and British Divisions landed on Omaha and Gold Beach in Normandy, France. Dated April 1944, this updated SECOND EDITION U.S. Infantry Division D-Day assault map shows OMAHA and GOLD BEACH and was revised with the TOP SECRET BIGOT series and was printed two months prior to the Allied invasion of Normandy.

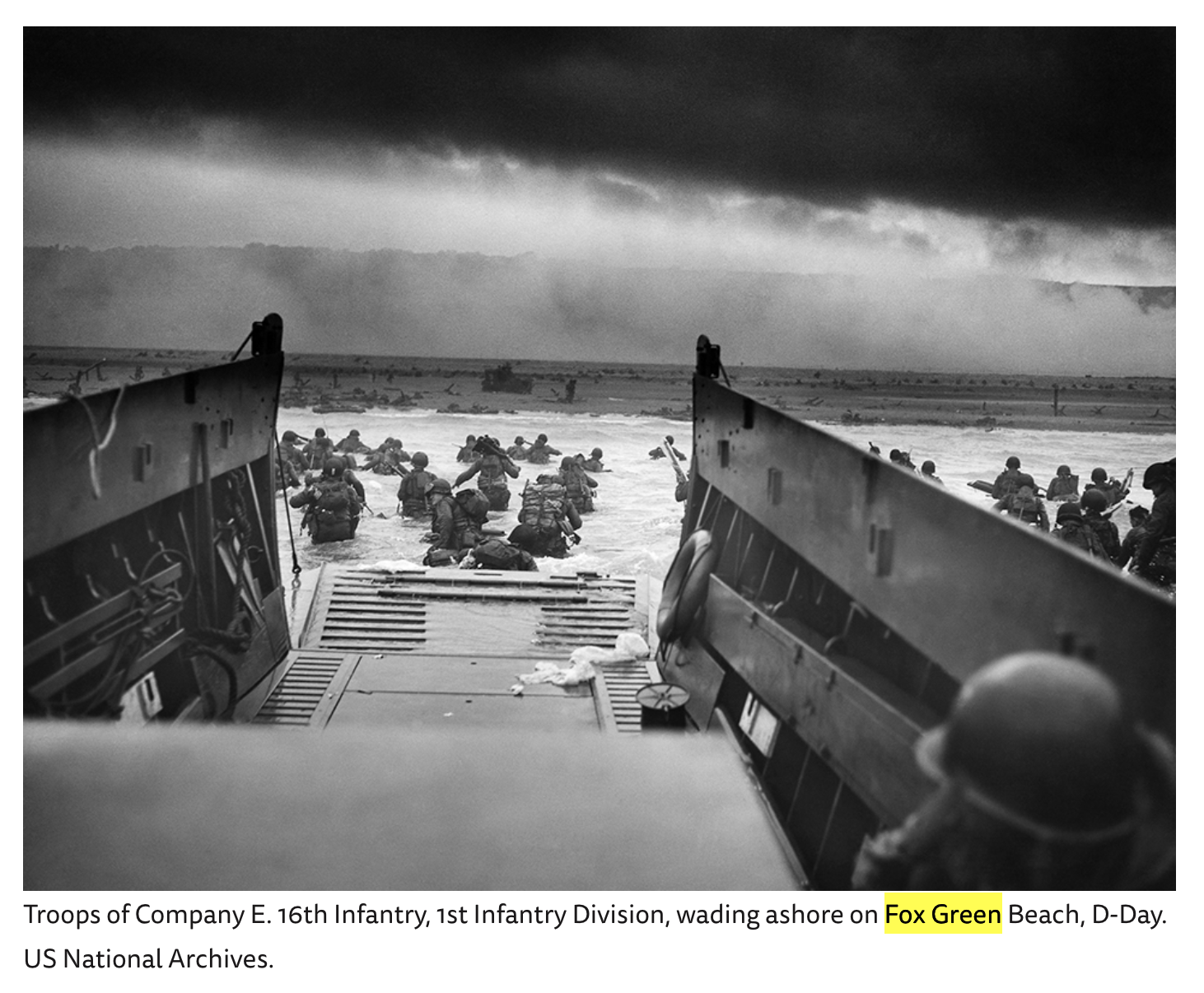

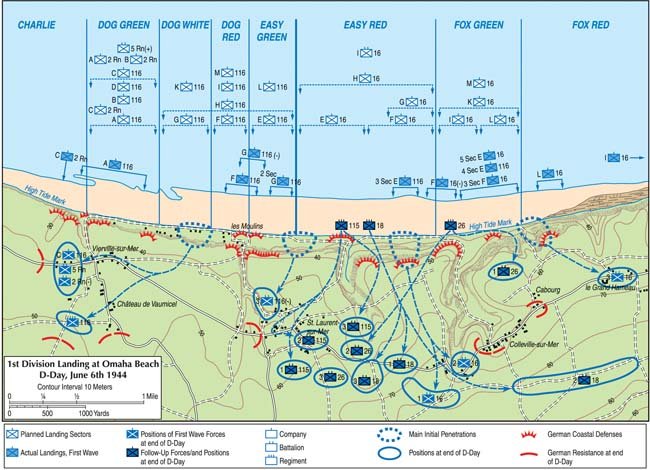

The troops in this first wave, known as Force O, were the 16th Infantry Regimental Combat Team of Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division—the Big Red One—which had already seen plenty of combat in North Africa and on Sicily. Attached to the 1st for most of the first day of this operation, known as “Overlord,” was the 116th Infantry Regimental Combat Team of Maj. Gen. Charles Gerhardt’s 29th Infantry Division—a well-trained division that had not yet experienced combat. The 16th, commanded by Colonel George A. Taylor, was scheduled to land on “Easy Red” and “Fox Green” beaches, two sections of a five-mile-long beachhead code-named “Omaha”; the 116th’s assigned sectors, just to the west of the 16th’s, were designated “Dog Green,” “Dog White,” and “Dog Red.”

Four attack transports—the USS Samuel Chase, USS Henrico, USS Dorothea M. Dix, and HMS Empire Anvil—had carried the 1st Infantry Division to a rendezvous point (dubbed “Piccadilly Circus”) in the middle of the English Channel. From there the assault troops transferred into smaller landing craft for the long run into shore. Companies E and F of the 16th Regiment’s 2nd Battalion were scheduled to hit Easy Red Beach a minute after the 32 amphibious Sherman tanks from A Company, 741st Tank Battalion reached shore at H-hour, 0630 hours. At the same moment, on Fox Green, the easternmost sector of Omaha Beach, Companies I and L would swarm ashore. The troops on Easy Red would be reinforced a half-hour later by the arrival of Companies G and H, while Fox Green would be backed up by Companies K and M. About an hour later, Lt. Col. Herbert C. Hicks, Jr.’s2 2nd Battalion would hit the shore, followed by the four companies of Lt. Col. Edmund F. Driscoll’s 1st Battalion and the guns of Lt. Col. George W. Gibbs’ 7th Field Artillery Battalion. Next would come Force B, Colonel George A. Smith, Jr.’s 18th Infantry Regiment and the attached 115th RCT from the 29th. In the early afternoon, Colonel John F.R. Seitz’s 26th Infantry Regiment would come ashore at Easy Red and Fox Green. That was the precisely timed, well-rehearsed plan but, as anyone who has ever been in combat will testify, the battle rarely sticks to the script.

On Fox Green Beach, things were as bad as on Easy Red. Five boat sections of F Company, 16th Infantry were scattered across a thousand yards of sand. Two sections of the company did manage to land close together in front of enemy positions, but were decimated by machine guns and mortars as they departed from their LCVPs. Six officers and half of the company became casualties in a matter of minutes. The remaining boat section of E Company, 16th Infantry reached the shore where water and sand were spouting in an endless flurry of artillery and mortar explosions.

At Easy Red and Fox Green, the leading companies of the 16th RCT were trapped on the beach. The only way to break out of the trap was for one man, or several, to risk their lives by crawling forward, armed with little more than wire cutters or Bangalore torpedoes—20-pound tubes packed with explosives—and expose themselves to enemy fire while they attempted to cut through the wire. Several brave men tried it; all were killed. Despite witnessing the suicidal nature of the mission, another soldier, Sergeant Phillip Streczyk of Wozenski’s E Company, attempted the impossible. With practically every German weapon within range zeroing in on him, Streczyk made a mad dash for the wire through a hail of bullets, snipped it, then waved for the rest of the troops to follow him.

D-Day FOX GREEN and OMAHA BEACH:

For the average American soldier at Omaha beach, death lurked with every step, especially near the strong points dubbed Wiederstandnesten or just “WN” by the Germans. These key fortifications were generally sited along the five natural beach exits, each of which had been created in the valleys between slopes by thousands of years of wind, rain, and erosion. In the 1st Infantry Division’s sector on the eastern side of Omaha, none of the exits were paved well enough to support armor or other heavy vehicles. Both the Americans and the Germans understood that these exits, or draws, offered the only sustainable way to get off the beach. The infantry would have to take the draws; the engineers would then follow up and pave them into real roads capable of handling large volumes of vehicle and troop traffic.

Looming over the Fox Green sector, in the heart of the 1st Division landing beaches, WN-61 directly overlooked the sea and a rocky, flat beach. Twelve German soldiers, under the command of a Sergeant Major Schnuell, comprised the garrison. WN-61 contained three Tobruks, (basically a dugout ring of reinforced concrete) one with a Renault tank turret, and two with machine guns and flame throwers. A formidable 50 millimeter antitank gun, in a dugout pit, faced westward. By far, the most powerful weapon at WN-61 was an 88-millimeter PAK gun ensconced in a concrete casemate that afforded near complete protection for the crew and only a small embrasure through which the menacing gun’s barrel protruded. The casemate was designed to shield the gun crew from naval fire and tank fire. The crew’s field of fire commanded all of Omaha beach. The gun could savage tanks, landing craft and soldiers alike. In fact, this 88, in combination with another one at WN-71, guarding the Vierville draw on the western edge of Omaha, in the 29th Division sector, bracketed the whole beach. Fortunately, a pair of American Sherman tanks knocked out the 88 within the first 30 minutes of the invasion.

The 50-millimeter gun proved to be a tougher nut to crack, something Staff Sergeant Raymond Strojny quickly realized on D-Day morning. The 25 year old Strojny was a Taunton, Massachusetts native who had once worked for Reed and Barton, a manufacturer of fine crystal and flatware. He had fought with his outfit since North Africa. His boat section leader, Lieutenant Otto Clemens, had been killed within a few minutes of landing. Strojny had then gathered up what men he could and dodged the heavy fire.

Even with the 88-millimeter gun out of commission, Sergeant Major Schnuell and the 12 German defenders of WN-61 creased the beach with devastating fire from the 50-millimeter cannon. The fortifications of WN-61 were perched on a knoll only about 40 yards away from the high water mark. This close proximity to Fox Green made the fire of the enemy defenders especially lethal and accurate. However, this was also a disadvantage—WN-61's closeness meant that the Americans could spot it and destroy it more readily than other unseen strong points on the bluffs.

Strojny watched in abject frustration, and anger, as the 50-millimeter gun destroyed three Sherman tanks along the beach. He raised his rifle and fired several ineffective shots at the gun crew. To have any chance against the 50-millimeter gun, he needed a heavier weapon. He looked around and called for a bazooka crew, but apparently the team from his section was either dead or wounded. “So I went in searching for a bazooka on the beach, knowing that that gun had to be knocked out to make our sector a success,” he later wrote. After searching for several minutes, he found an unfamiliar sergeant who was carrying a bazooka. Strojny instructed the sergeant to fire his bazooka at the 50-millimeter, but the man said he could not see it. Sergeant Strojny pointed it out to him. The other soldier, who did not seem especially eager to comply with Strojny’s wishes, told him that he could not shoot because he had no one to load his bazooka. Strojny quickly loaded a rocket into the tube. The man fired and missed badly. Strojny crawled over to him, loaded another rocket, and then took cover about five yards away. The man fired and missed again.

Most likely, these two shots attracted the attention of an enemy mortar crew. A round zipped in and exploded in the five yard gap between the two sergeants, badly wounding the unfamiliar sergeant. Strojny was fine. He grabbed the bazooka and took off in search of a better firing spot. The 50-millimeter gun continued spitting out shells at targets on the beach. The monotonous rapidity with which the gun spewed death and destruction infuriated the young sergeant. He glanced at the bazooka and noticed that it had been damaged by the mortar fragments. “But I had to try it,” he said, “maybe it was not damaged enough, I had to take the chance.” It was not uncommon for a defective bazooka to explode in the face of a shooter. He loaded a rocket into the tube, no small feat since it required the loader to connect an arming wire to the rear of the bazooka while making sure the rocket did not slide down the tube and out the front, perhaps arming itself in the process. The job of loading and firing was designed for two people, but he was determined to do it himself. He managed to fire a pair of shots but they had no effect. Bazooka gunners were trained to glance backward before firing and make sure no one was in the line of the weapon’s back blast. But, in the excitement of the moment, Strojny forgot to do that. “When he fired the bazooka, he was not too careful about seeing who was behind him,” T5 James Thomson, a radioman from the same company who witnessed Strojny’s exploits, later said. “The back blast burned one of the wounded men who was lying there on the beach.” Fortunately, the wound was not serious, “but at least it caught him and he knew something had happened.”

Strojny continued his search for the best vantage point to attack the 50-millimeter gun. All alone, he dashed forward to a grassy minefield. Somehow Strojny crossed the minefield without touching off any explosions and found a spot with a good field of fire. He fired several times and scored at least two hits in the vicinity of the 50-millimeter but still it kept firing. “I ran out of ammunition, then went back to [the] beach, found more ammunition, came back to [the] bazooka, took up firing again.” According to a post action interview, he fired six rounds, each one of which hit the gun or in its vicinity. The final rocket detonated a nearby ammunition dump. Flames roared in and around the gun pedestal. The explosion and the fire finally put the gun out of commission and probably killed at least two of Sergeant Major Schnuell’s defenders. “A number of dead were observed,” the interview claimed, “and only one German was seen to escape.” Sergeant Strojny grabbed his M1 Garand and fired at the fleeing soldier. At the same time, an enemy rifleman spotted him and fired. A bullet tore through his helmet just above his left eye. Instead of penetrating his skull, it deflected to the left, circled his head and exited his helmet near his left ear, leaving the fortunate Strojny with only a superficial flesh wound.

If he was chastened by this close call, it did not show. He tossed the empty bazooka aside, rounded up a mixed group of soldiers and began to lead them through the minefield to attack the remaining machine gun positions of WN-61. Several times he had to urge men forward, particularly those who did not know him. His experience and competence were self-evident, though, especially for those who were new to combat that day. Indeed, several survivors later told an Army historian that they were “glad to follow soldiers who had combat experience and who seemed to know what they were doing.”

One of Strojny’s men, Private Charles Rocheford, stepped on a mine that blew his hand off. The records of Strojny’s F Company, 16th Infantry claim that his group silenced at least two machine gun posts and killed seven enemy soldiers. One American soldier was killed, another wounded. The destruction of the 50-millimeter gun and several other emplacements (not just by Strojny but other F Company soldiers) within WN-61 relieved some of the intense pressure the Germans were applying against Fox Green. Strojny’s elimination of the 50-millimeter gun, in particular, was a crucial accomplishment that saved many American lives. It was the first major step in the vital mission of securing the eastern flank of Omaha Beach. Sergeant Strojny inherently understood this. Like any good NCO, he possessed a keenly practical sense of how to get a job done. But his actions also stemmed from a powerful need to set an example for others.

For his actions and his leadership, he received the Distinguished Service Cross. Amazingly, the concrete casemate of WN-61, onetime location of the 88 and 50-millimeter guns, is now a private home. Any visitor to Omaha Beach can observe it and, in that short instant, catch a fleeting glimpse of what Sergeant Strojny saw on D-Day.