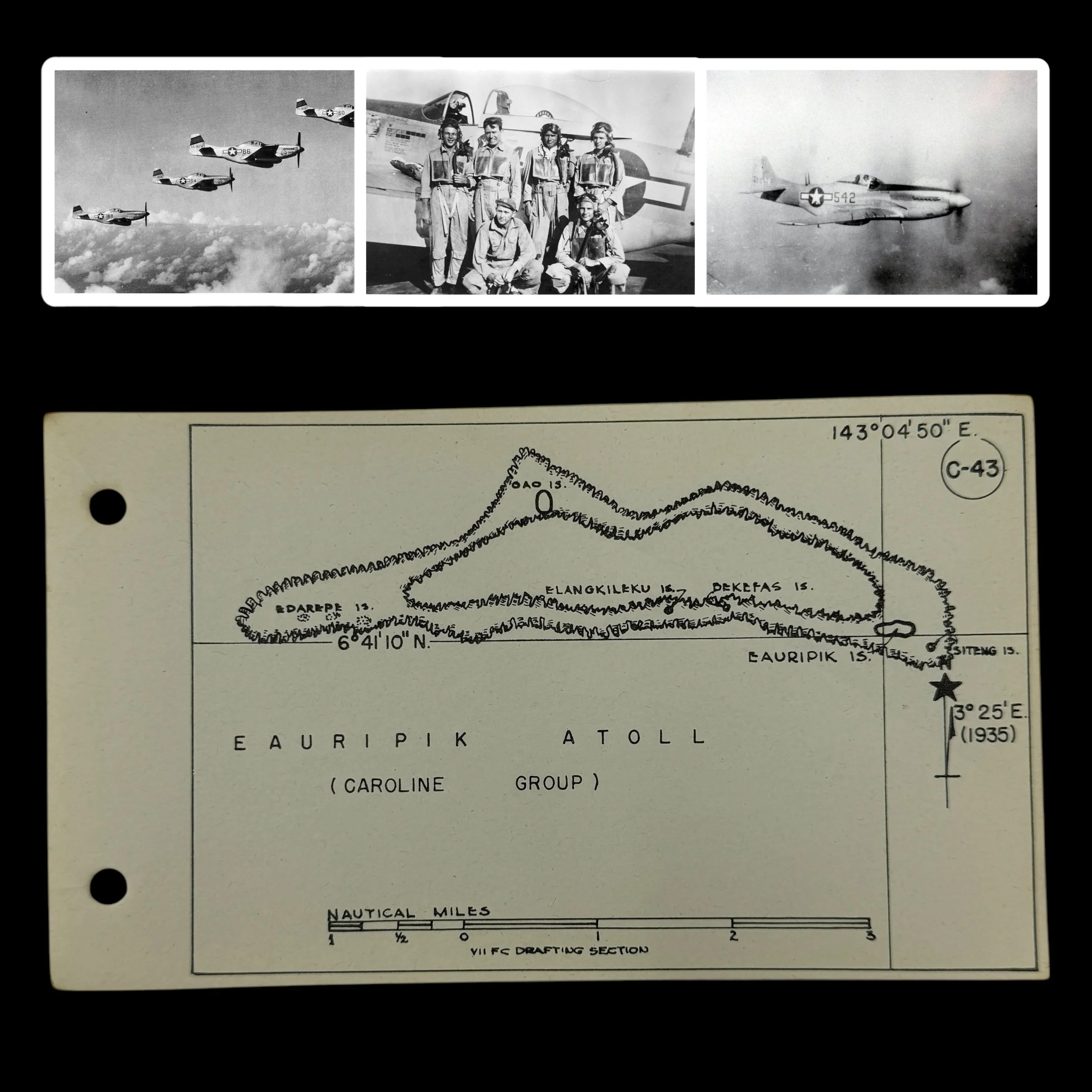

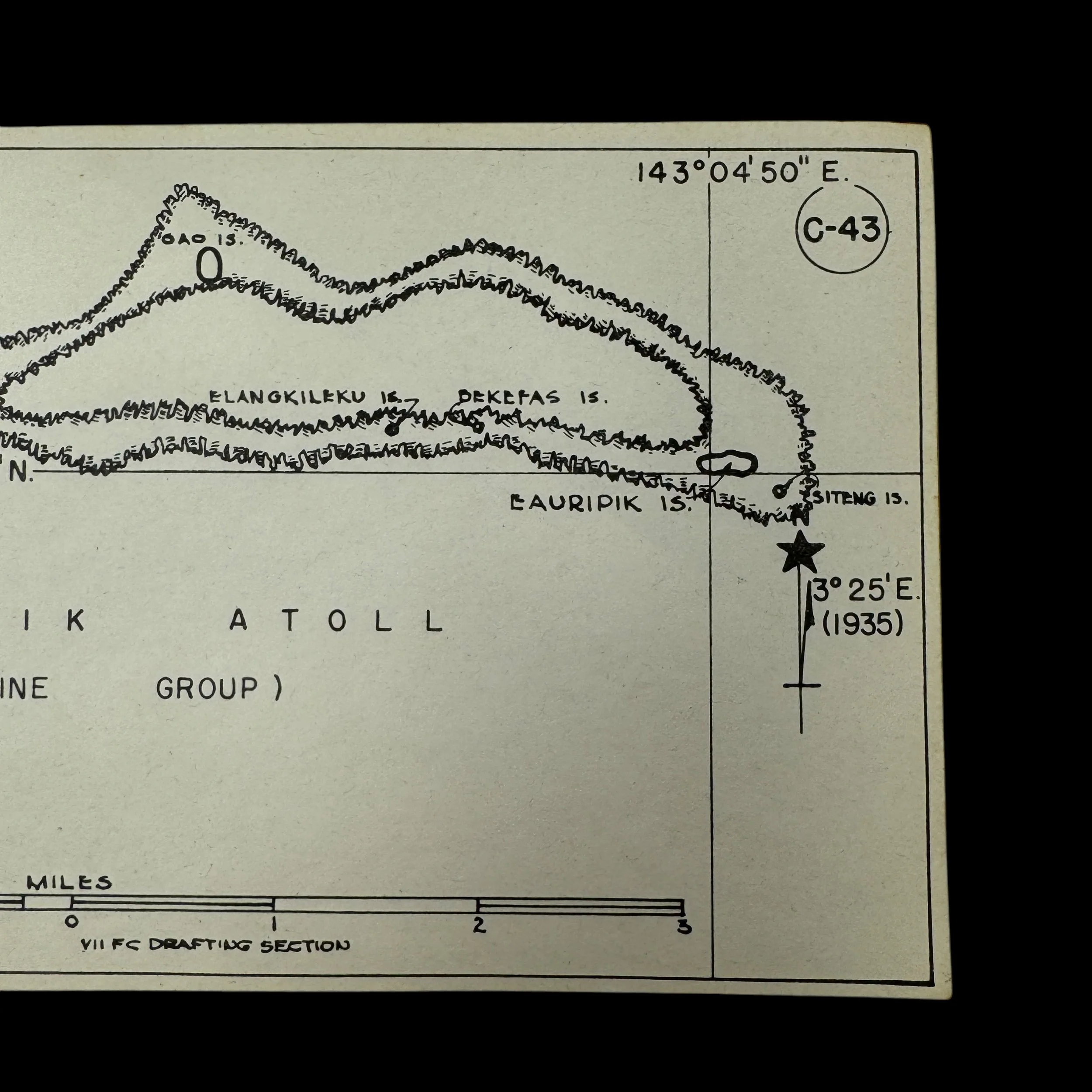

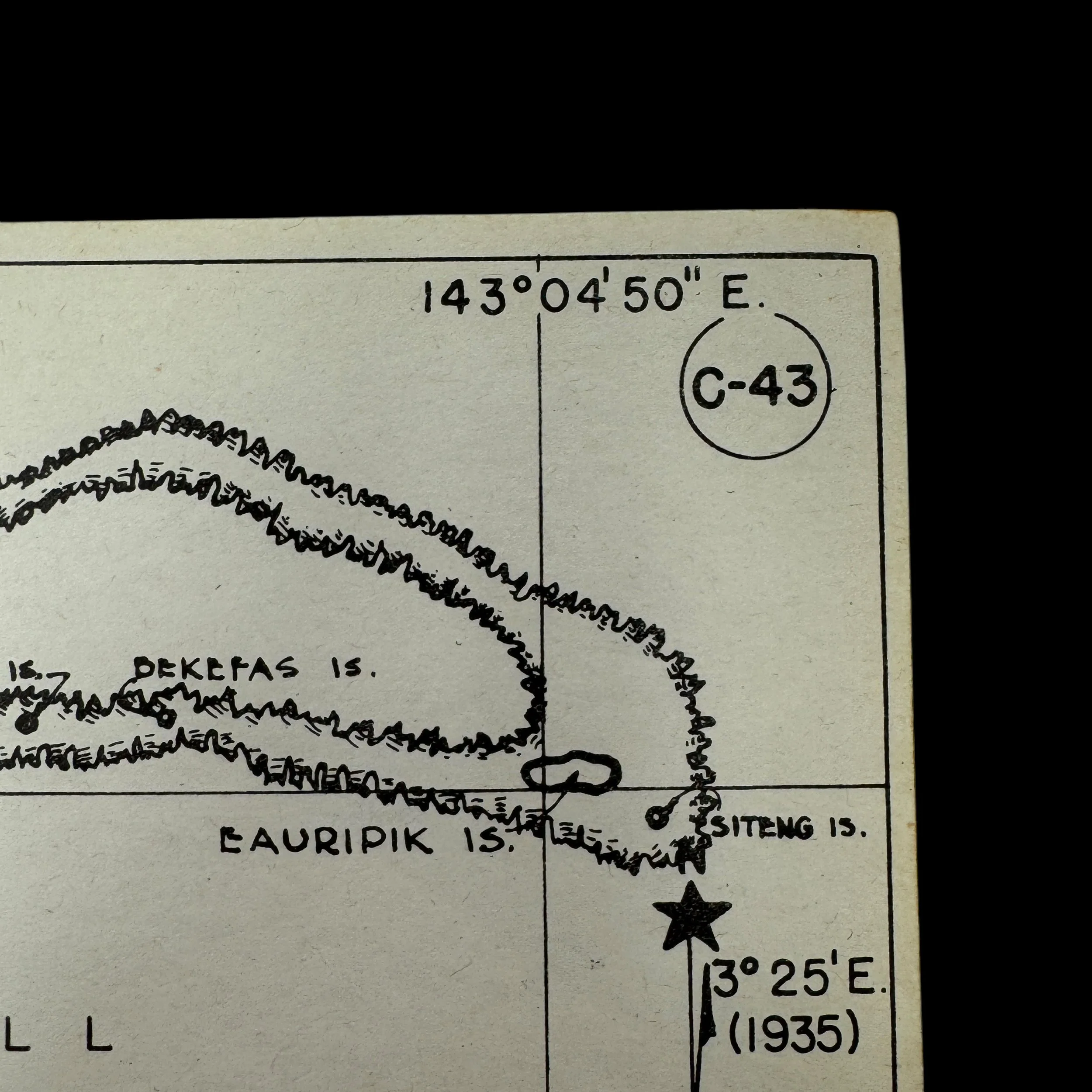

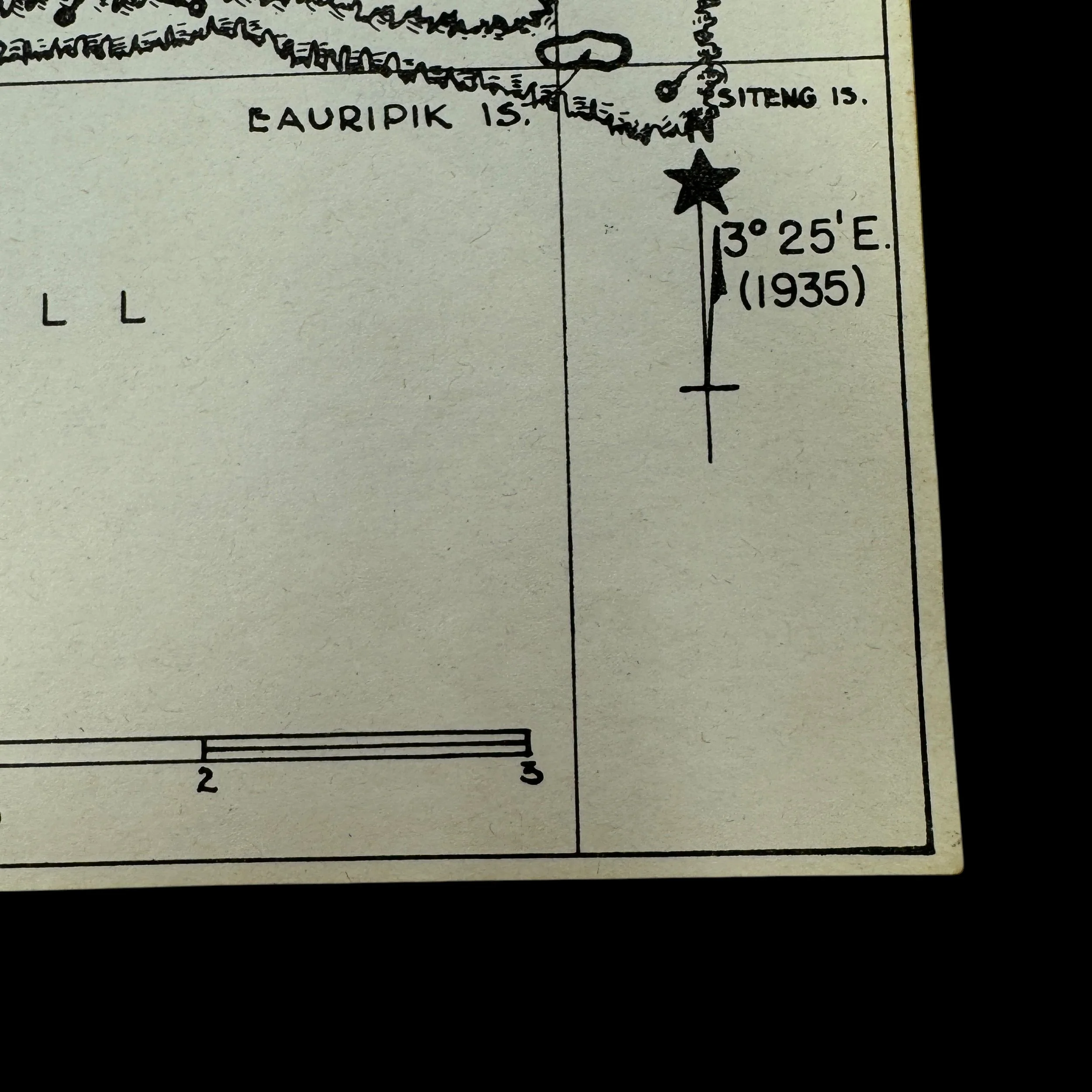

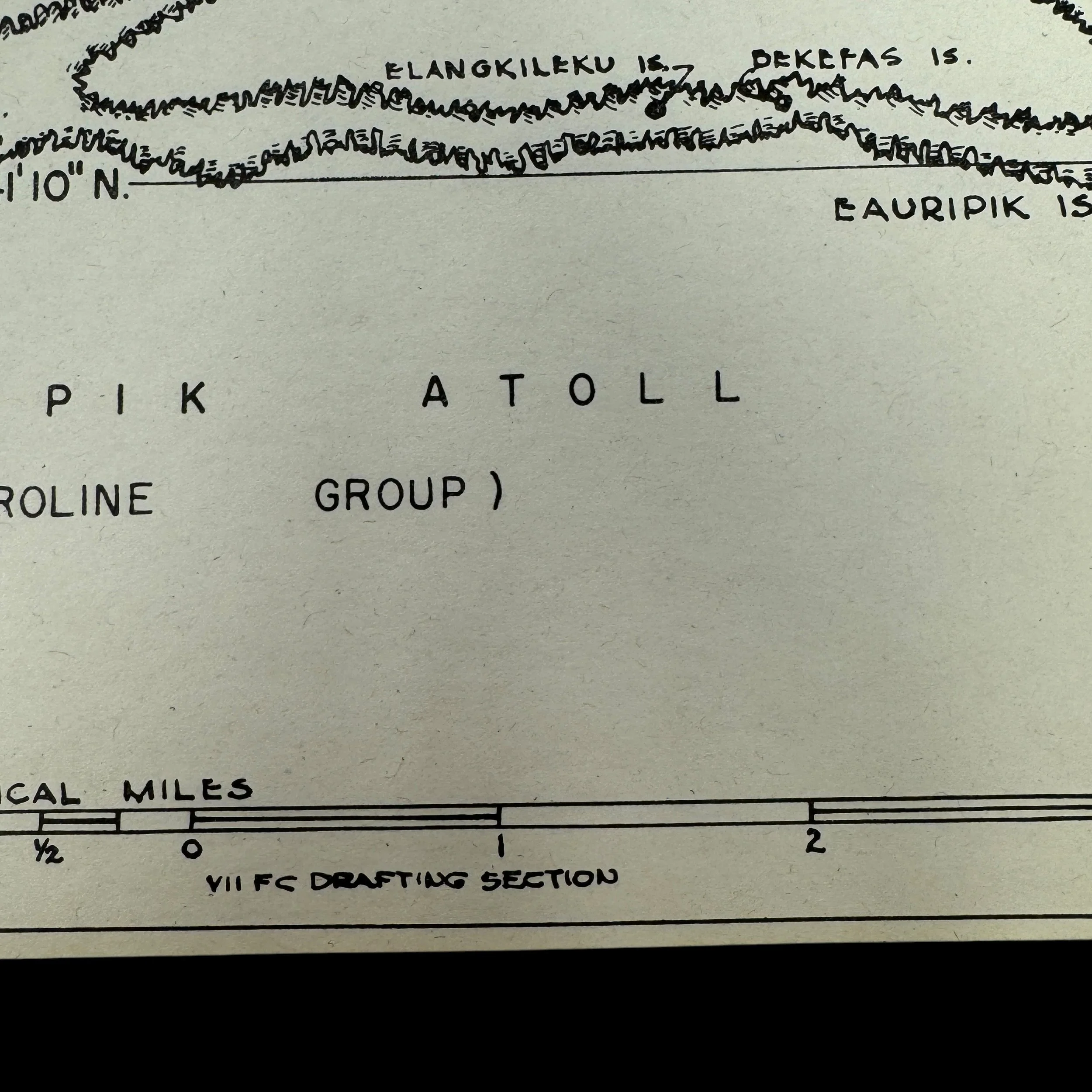

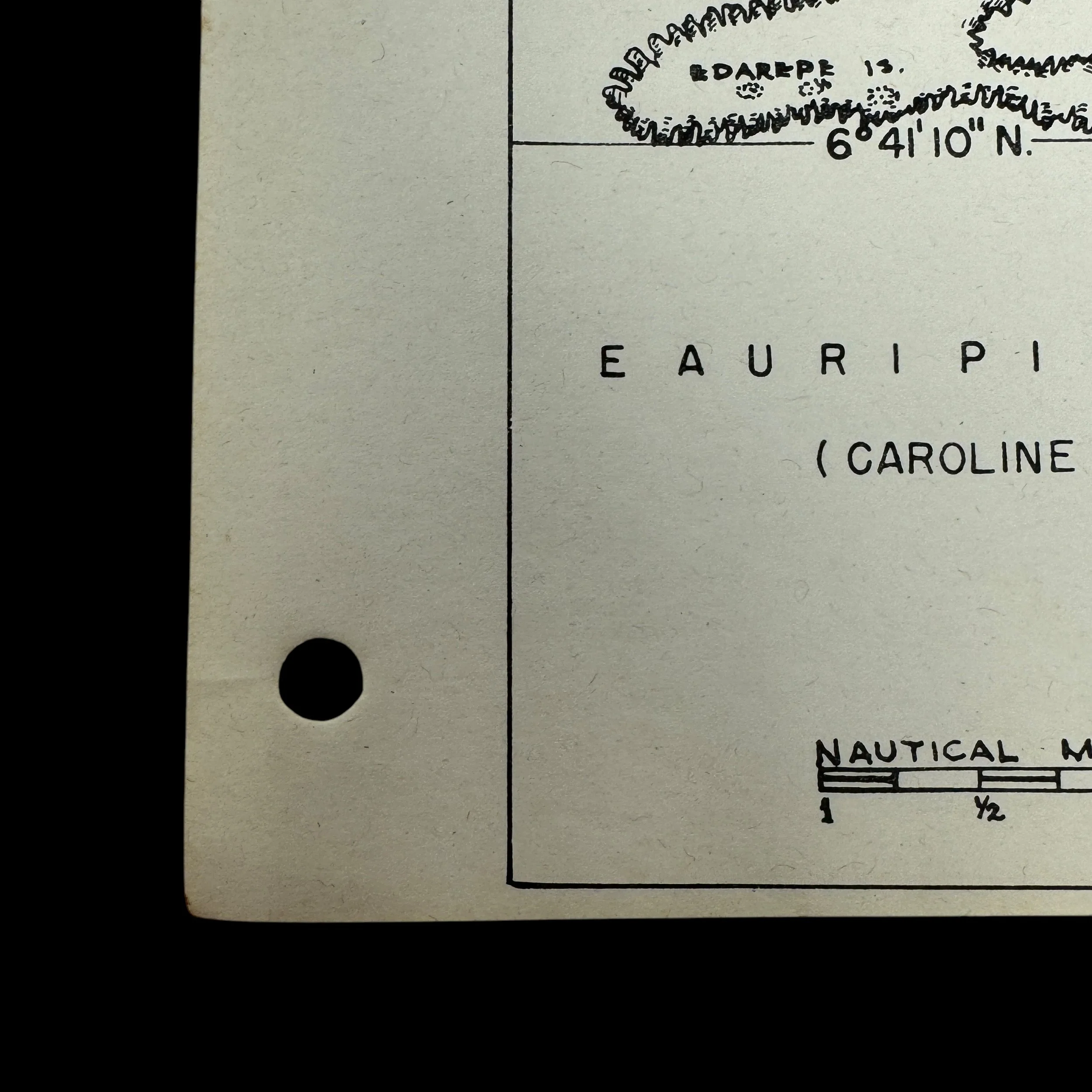

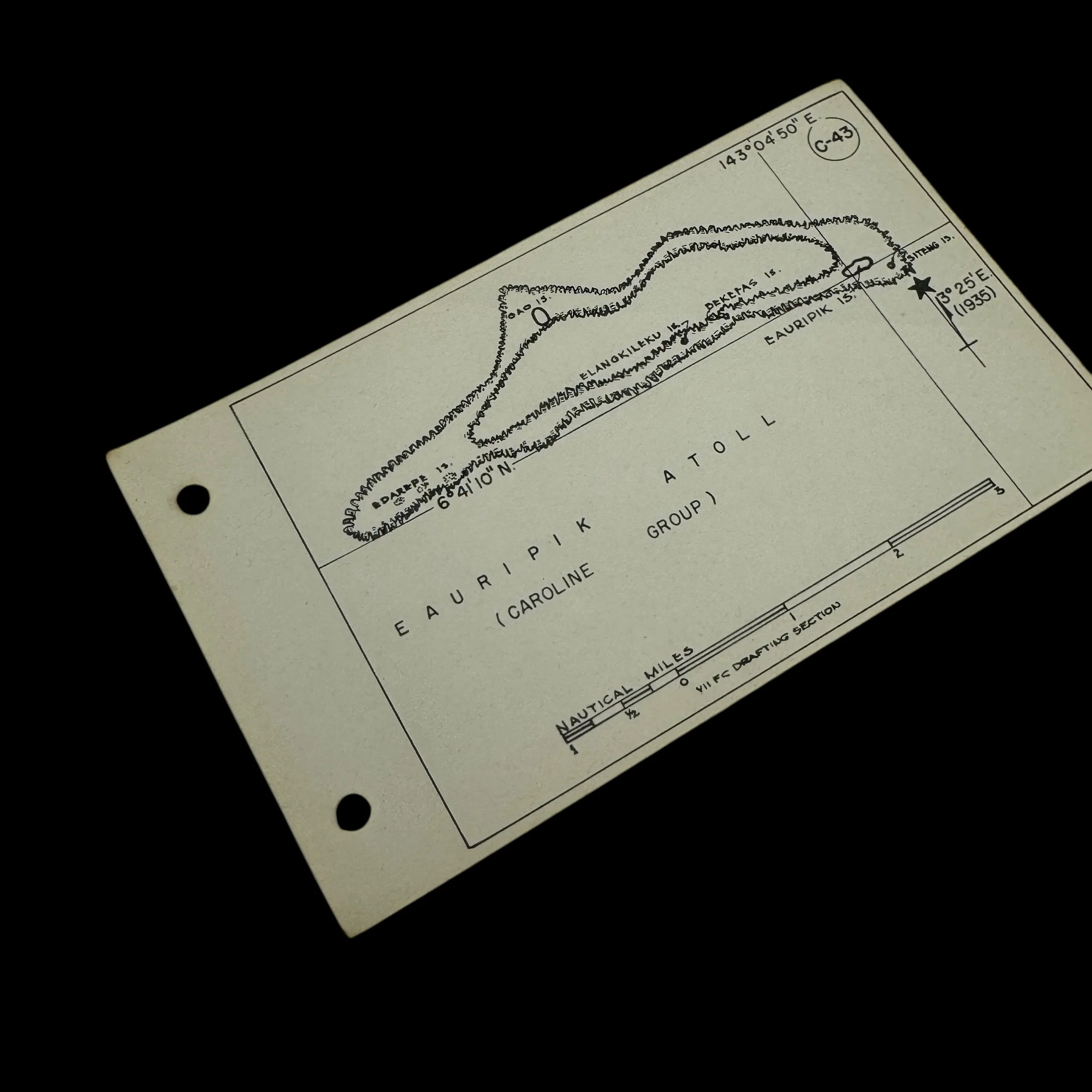

RARE! WWII VII Fighter Command P-51 Mustang Pilot Eauripik Atoll (Caroline Group) "Kneepocket" Flight Combat Map

RARE! WWII VII Fighter Command P-51 Mustang Pilot Eauripik Atoll (Caroline Group) "Kneepocket" Flight Combat Map

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

“As part of the Seventh Air Force, the VII Fighter Command P-51 pilots were instrumental in securing U.S. air superiority, conducting long-range escort missions, and supporting the strategic bombing campaign against Japan. Their deployment in the Marianas Campaign was pivotal to the success of the island-hopping strategy and the eventual destruction of Japan’s war-making capabilities”

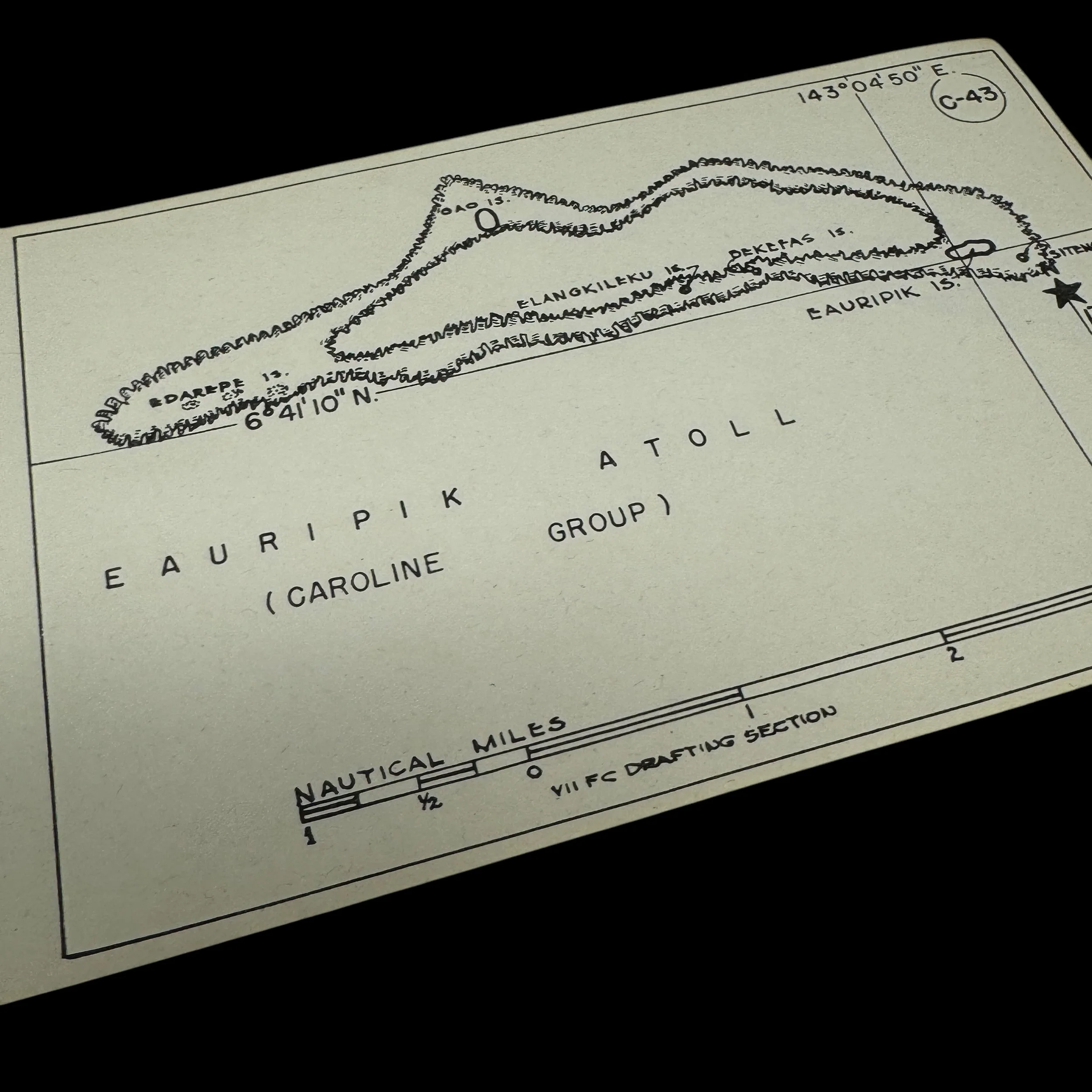

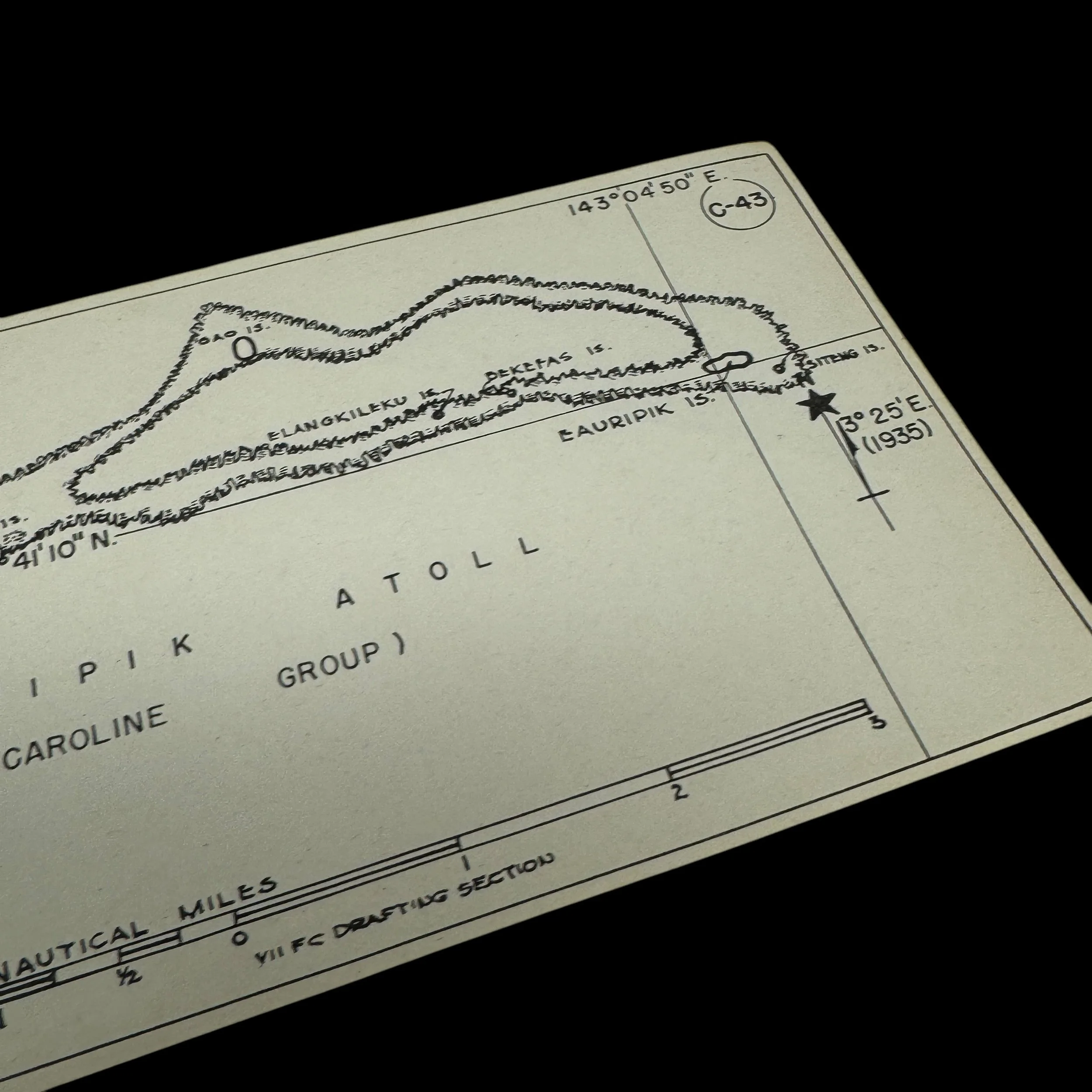

Type: Original World War II VII Fighter Command “Kneepocket" Flight Map Specially Made For P-51 Mustang Pilots of the Seventh Air Force’s VII Fighter Command (Field Printed at VII Fighter Command Forward Operating Airfield in the Pacific Theater)

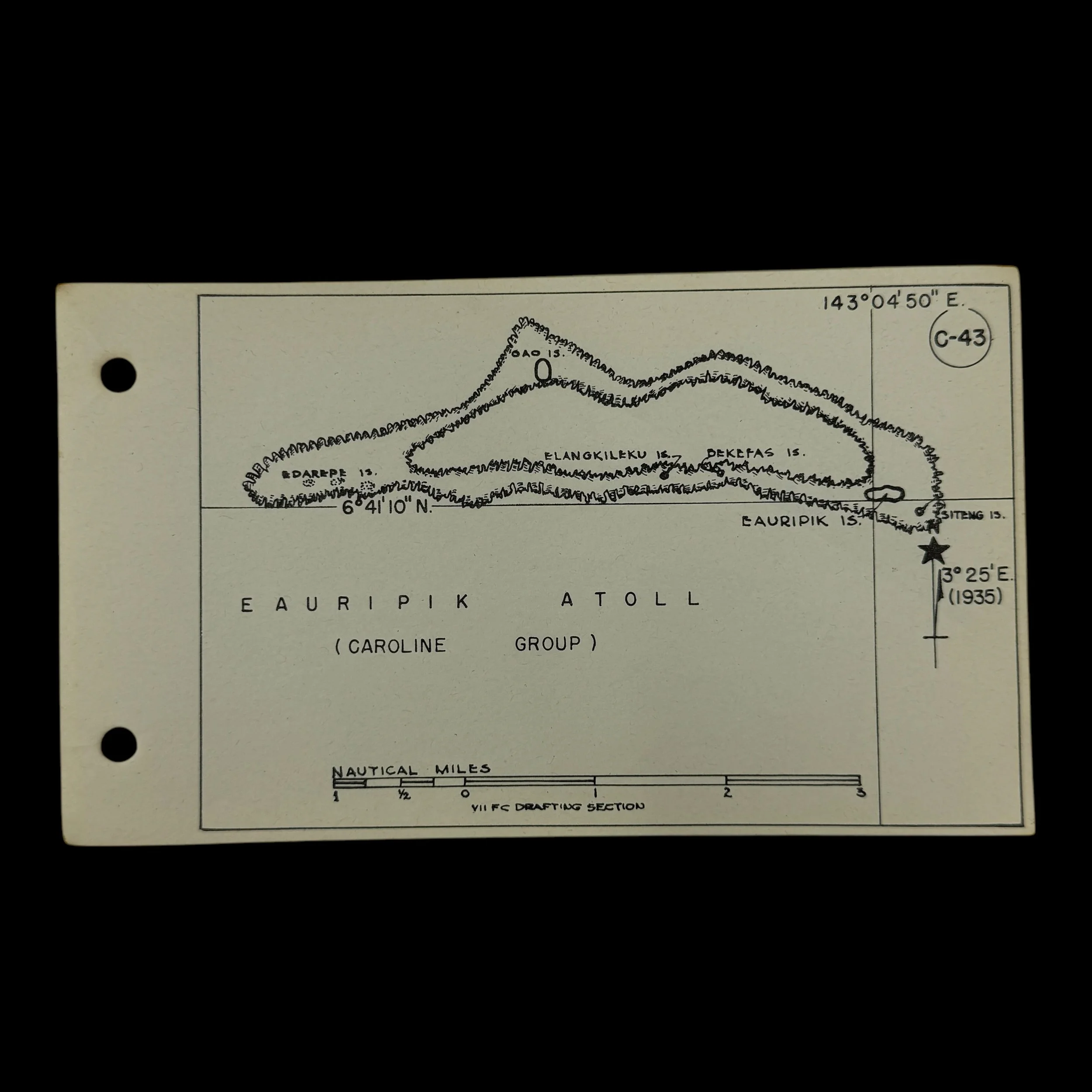

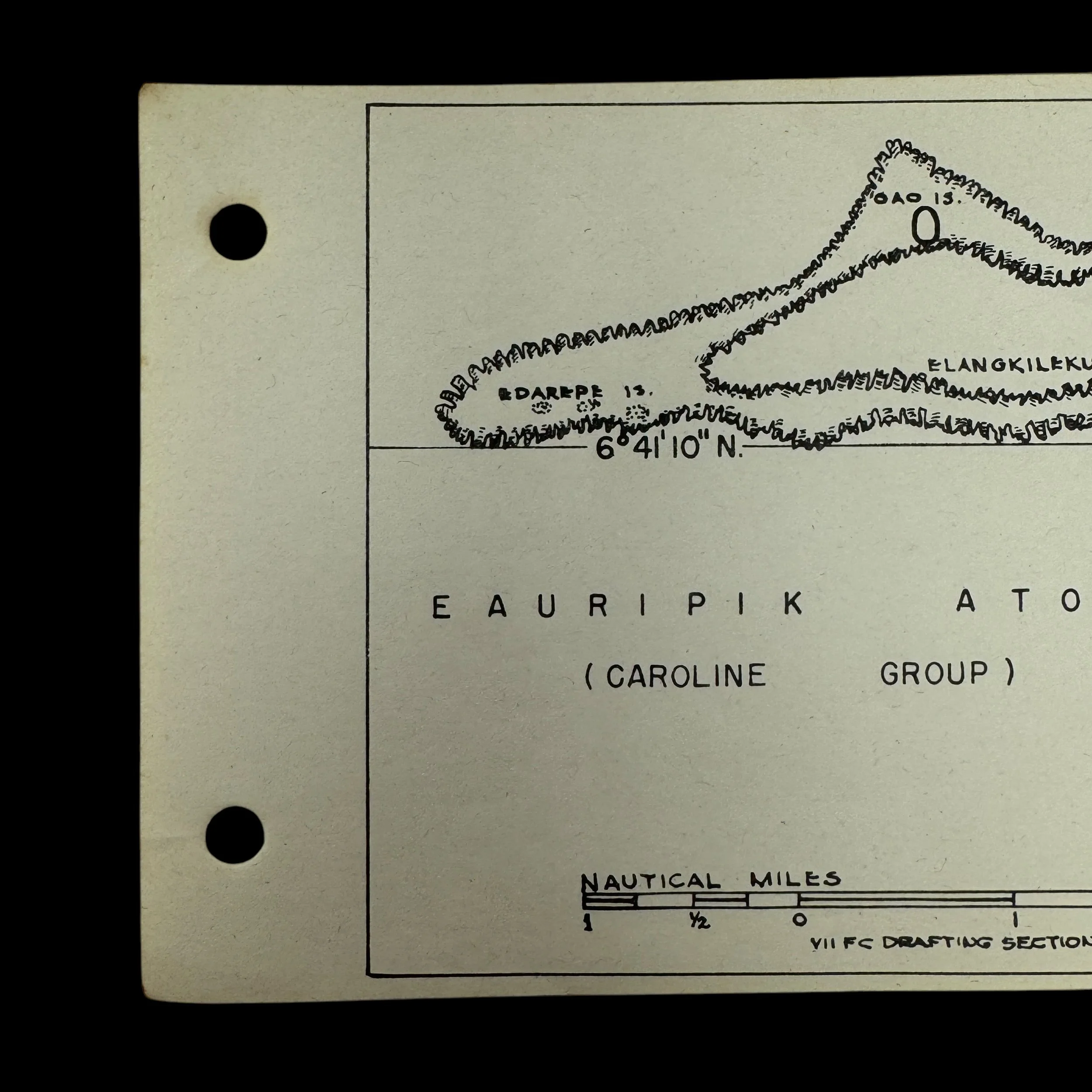

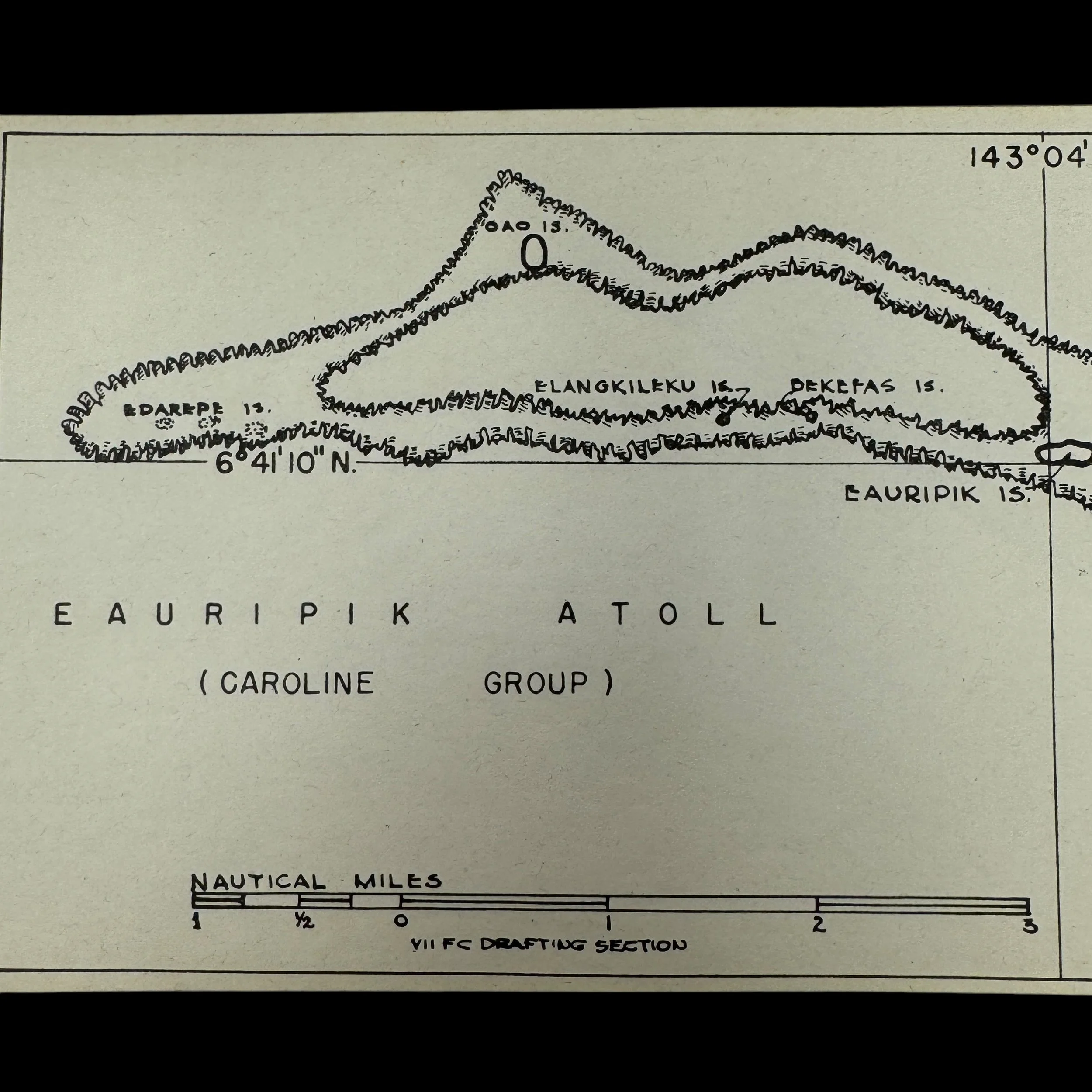

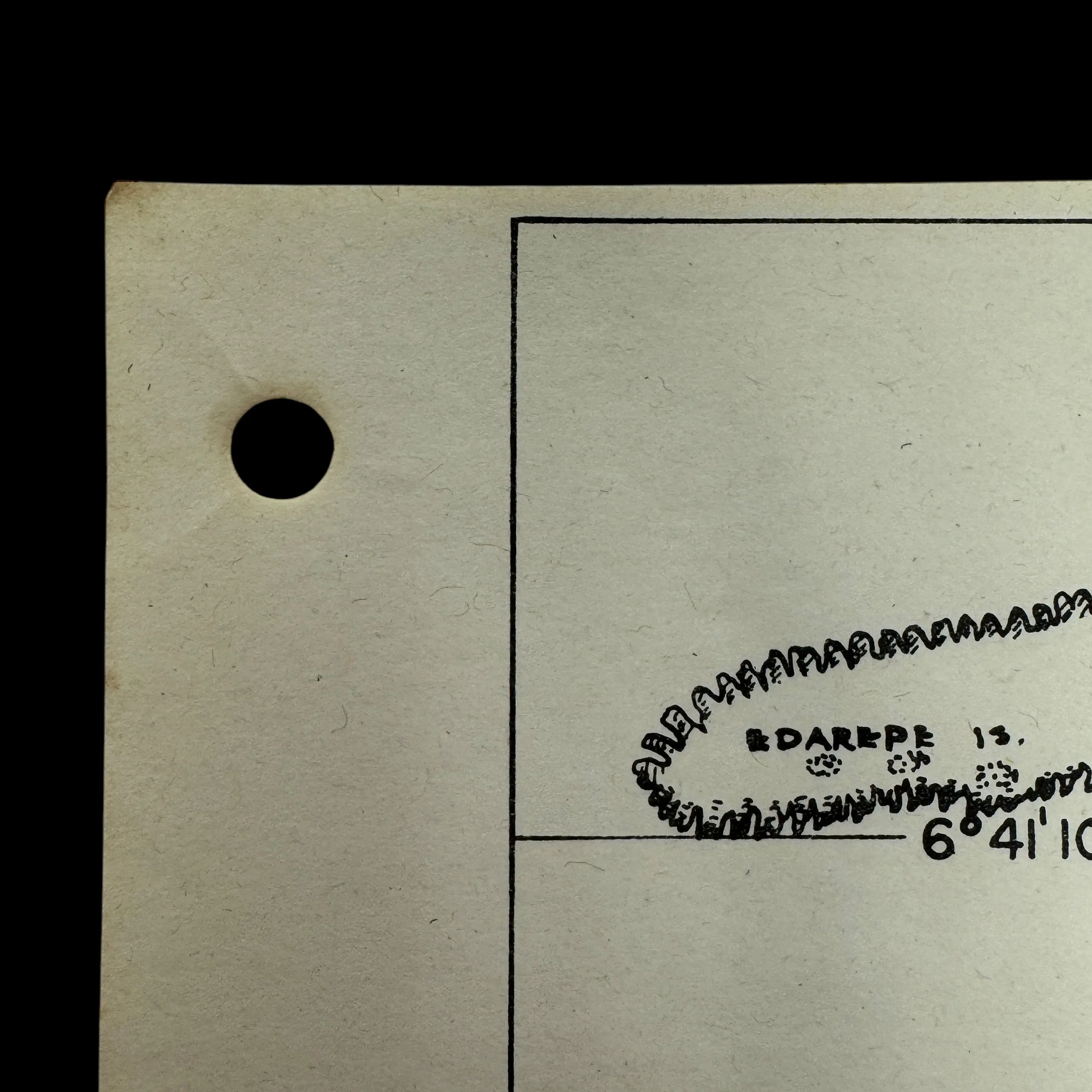

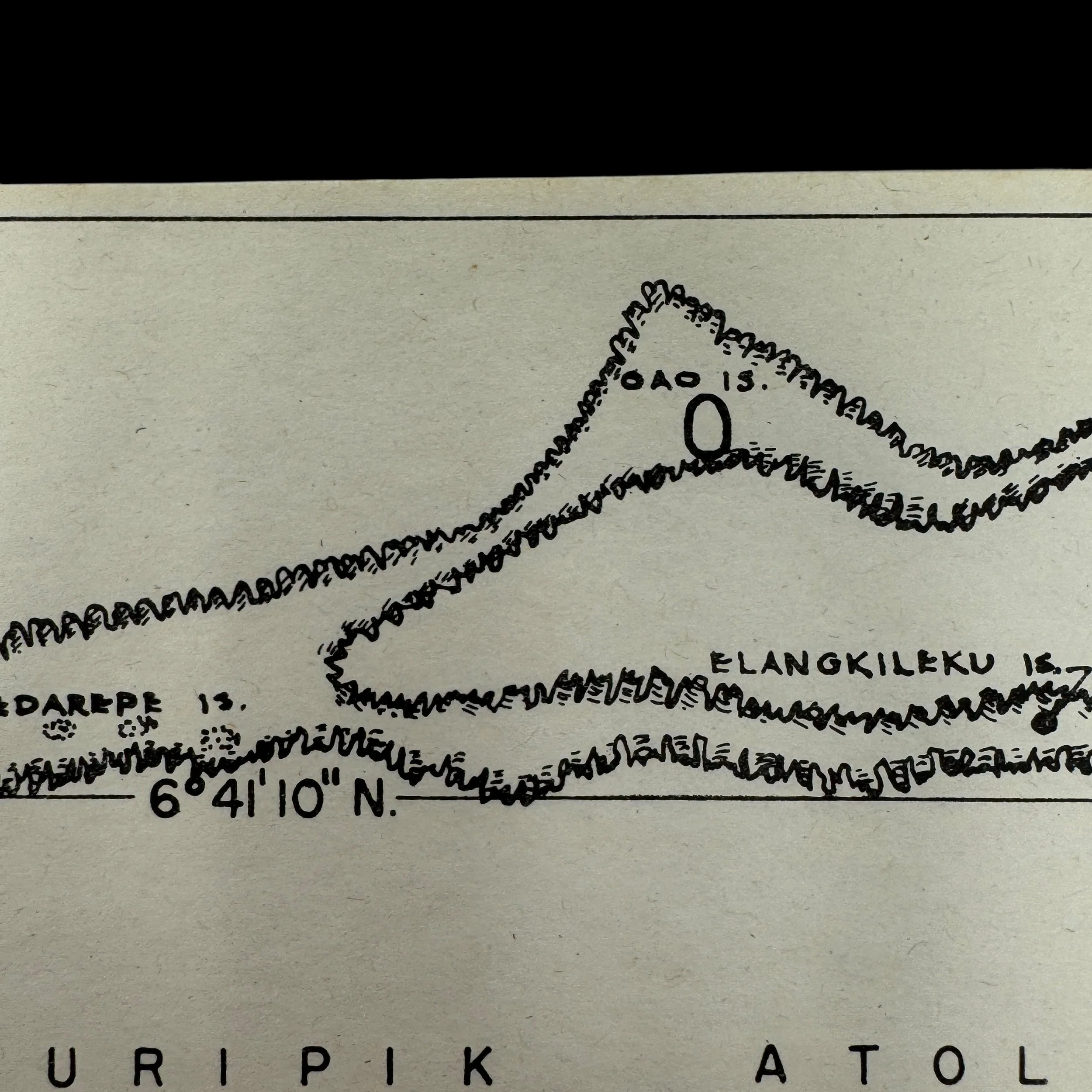

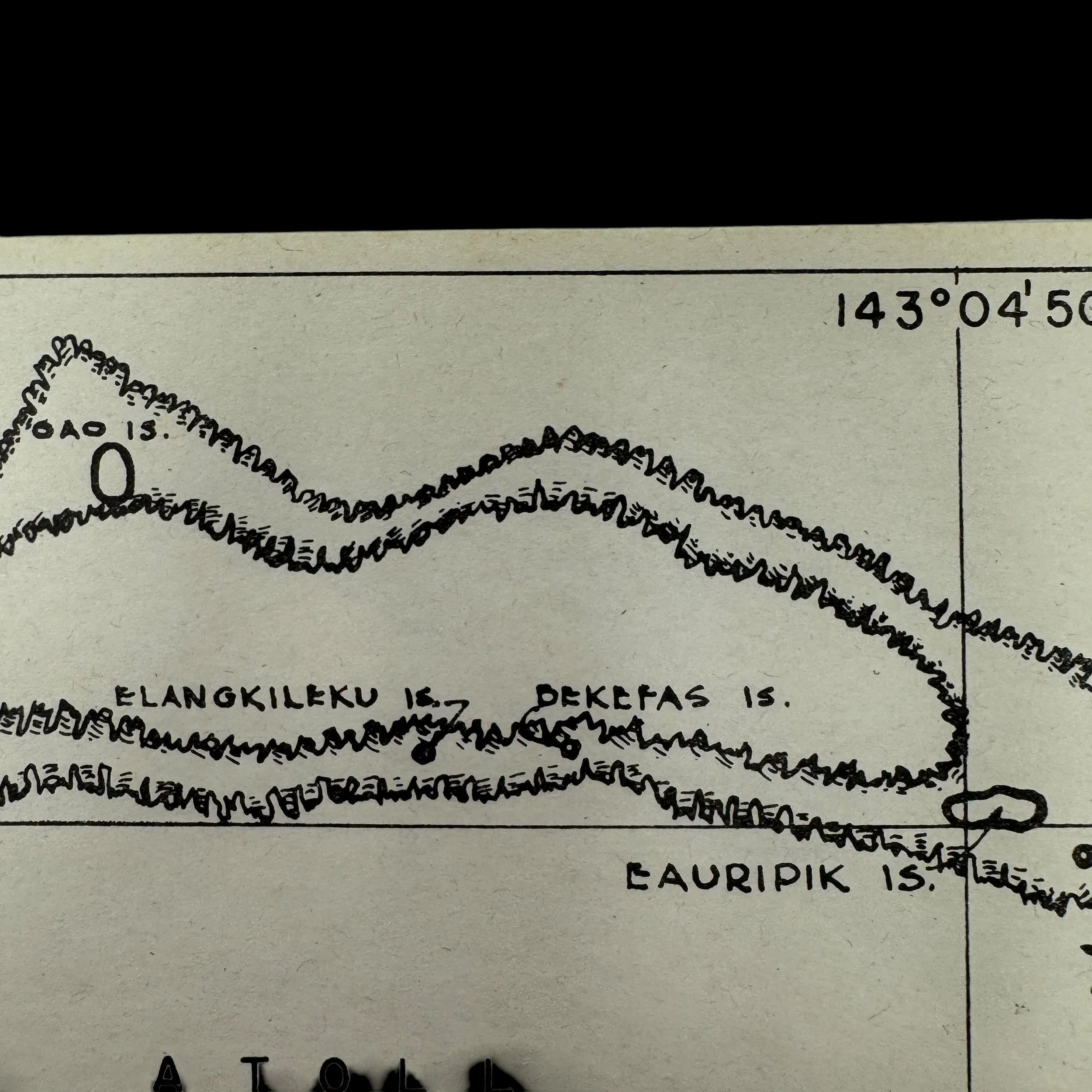

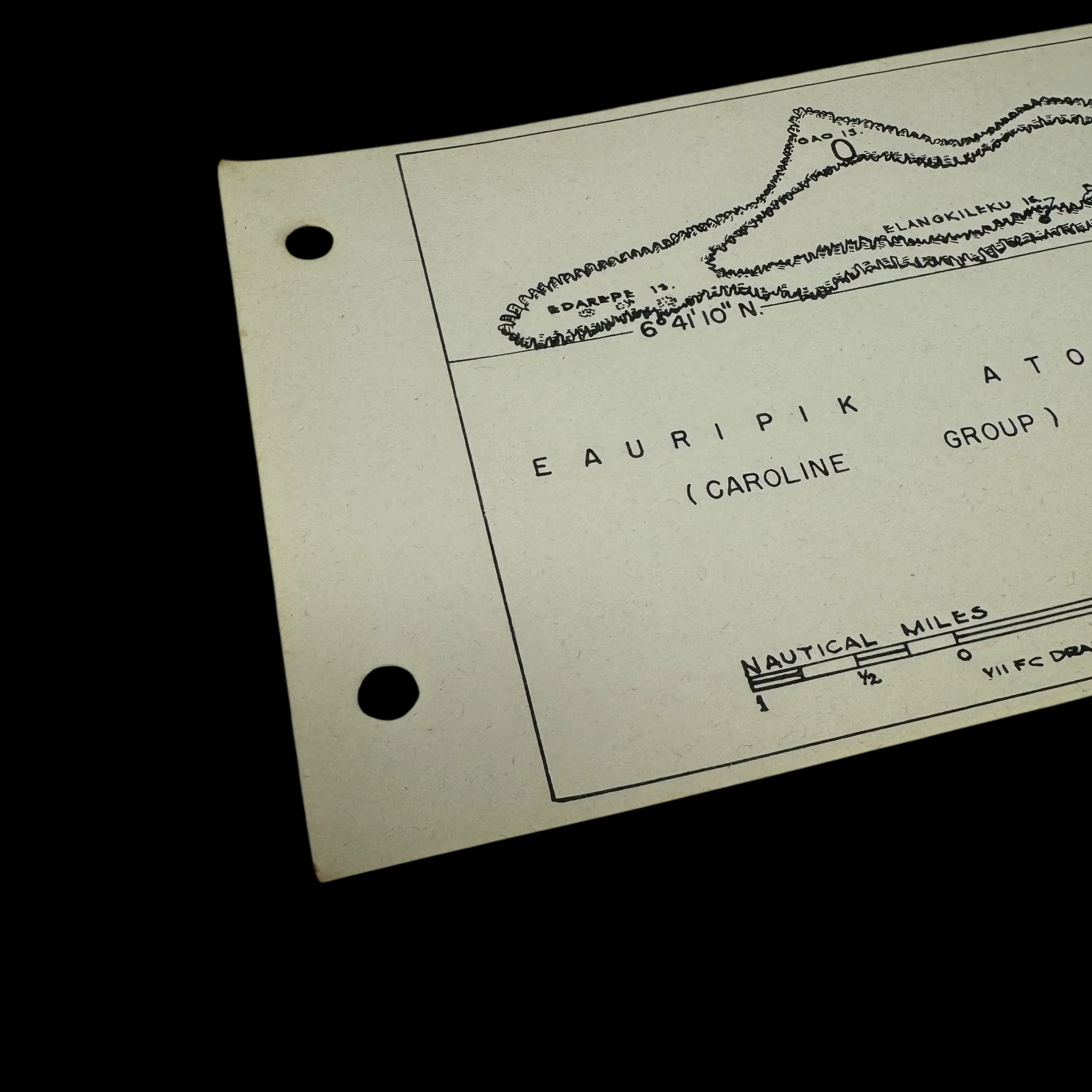

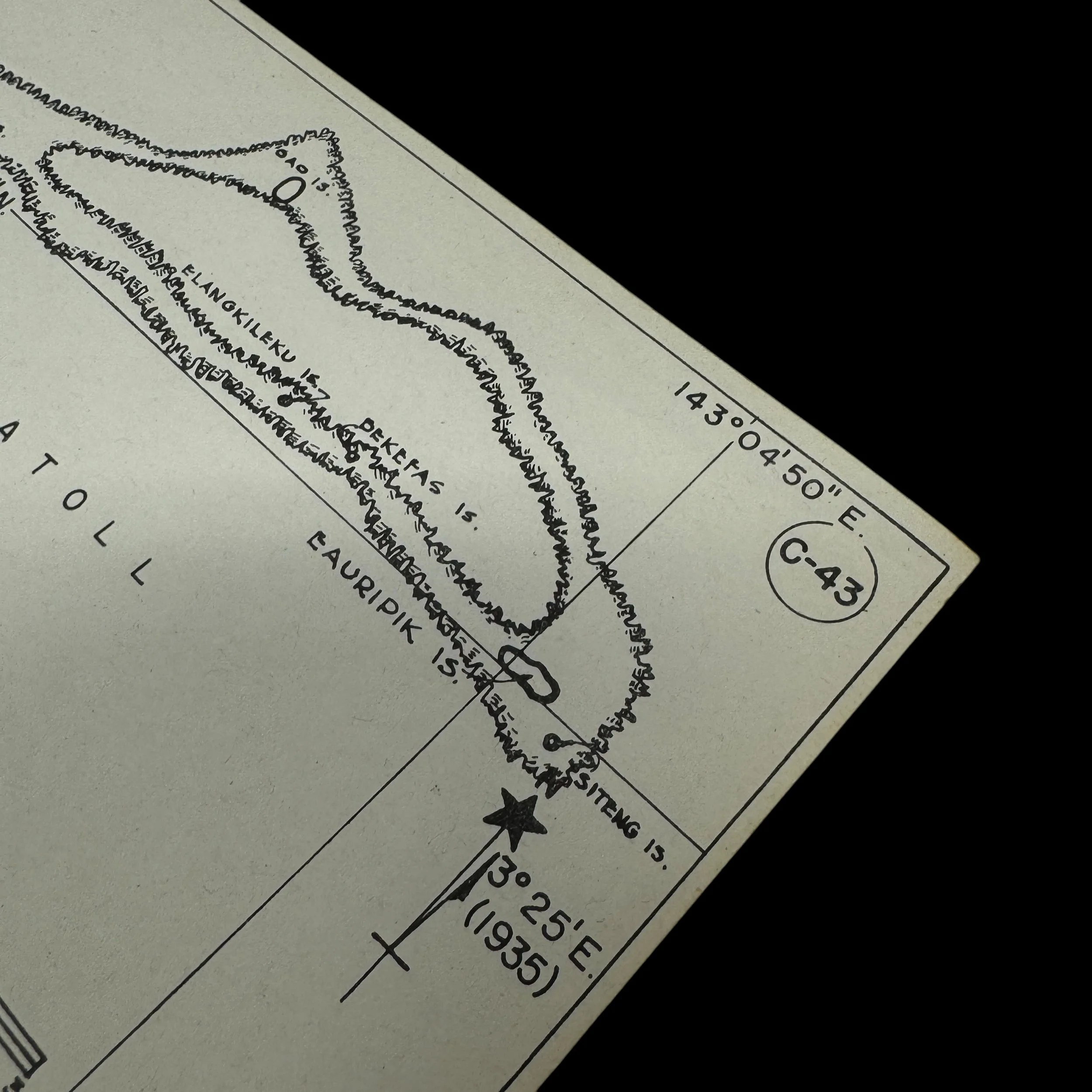

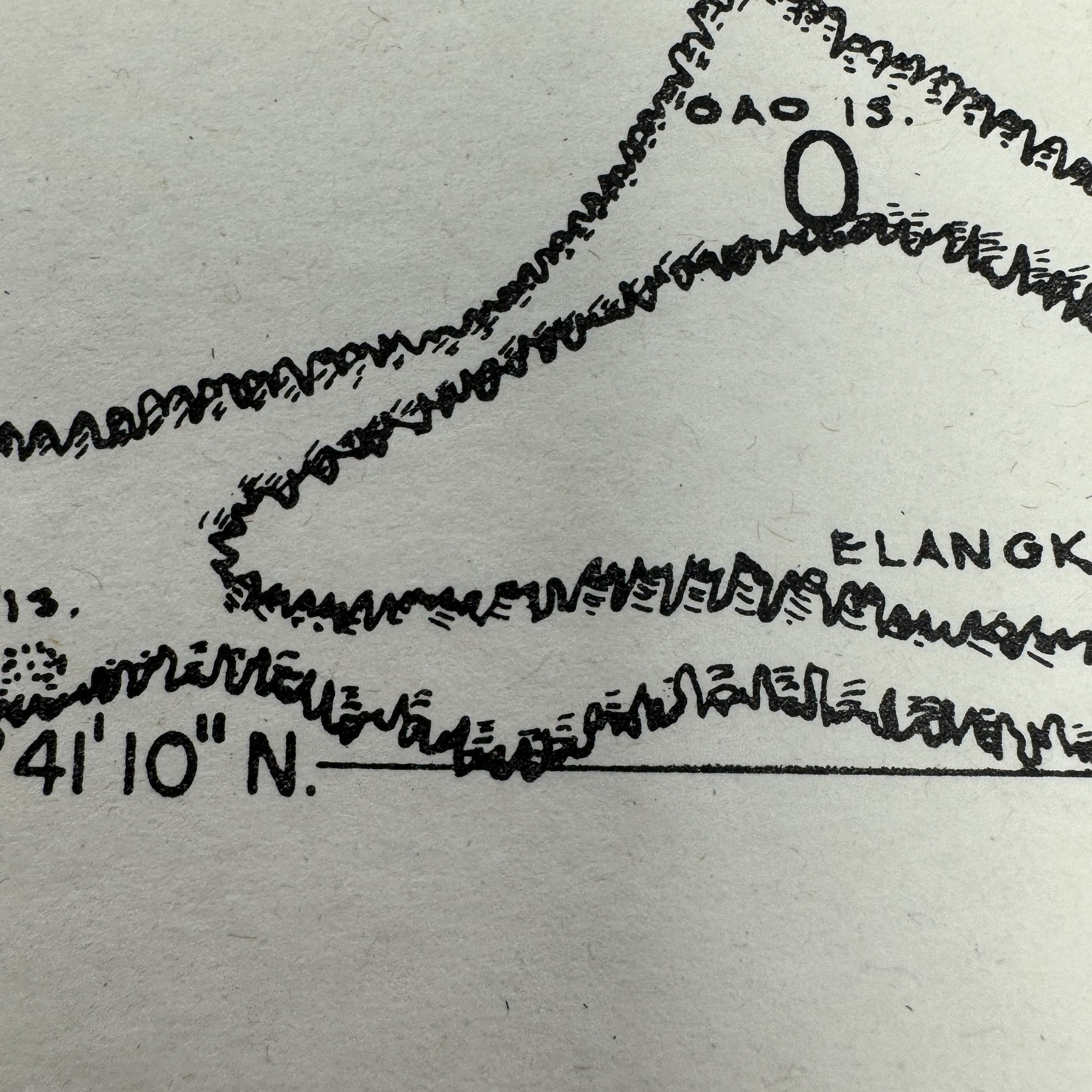

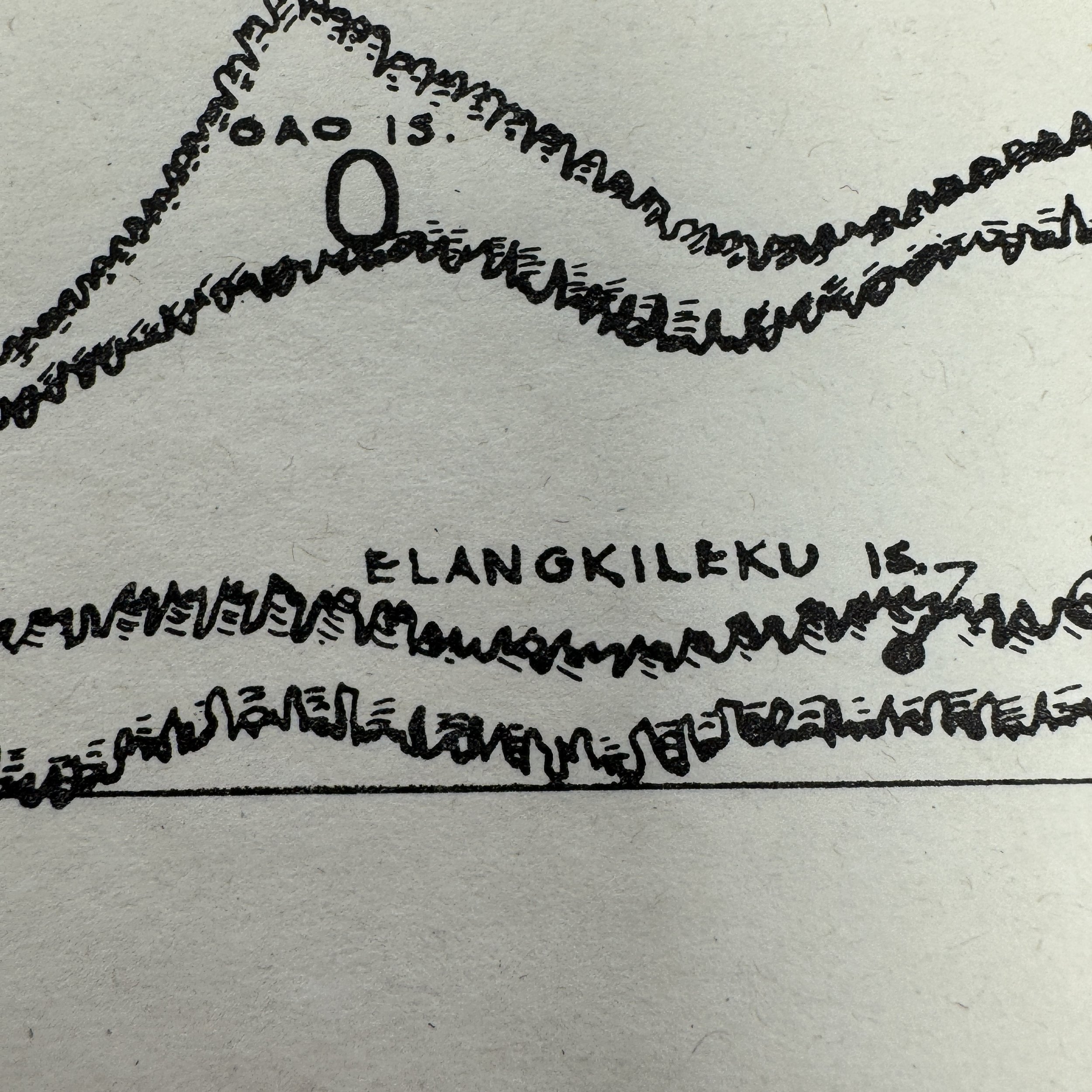

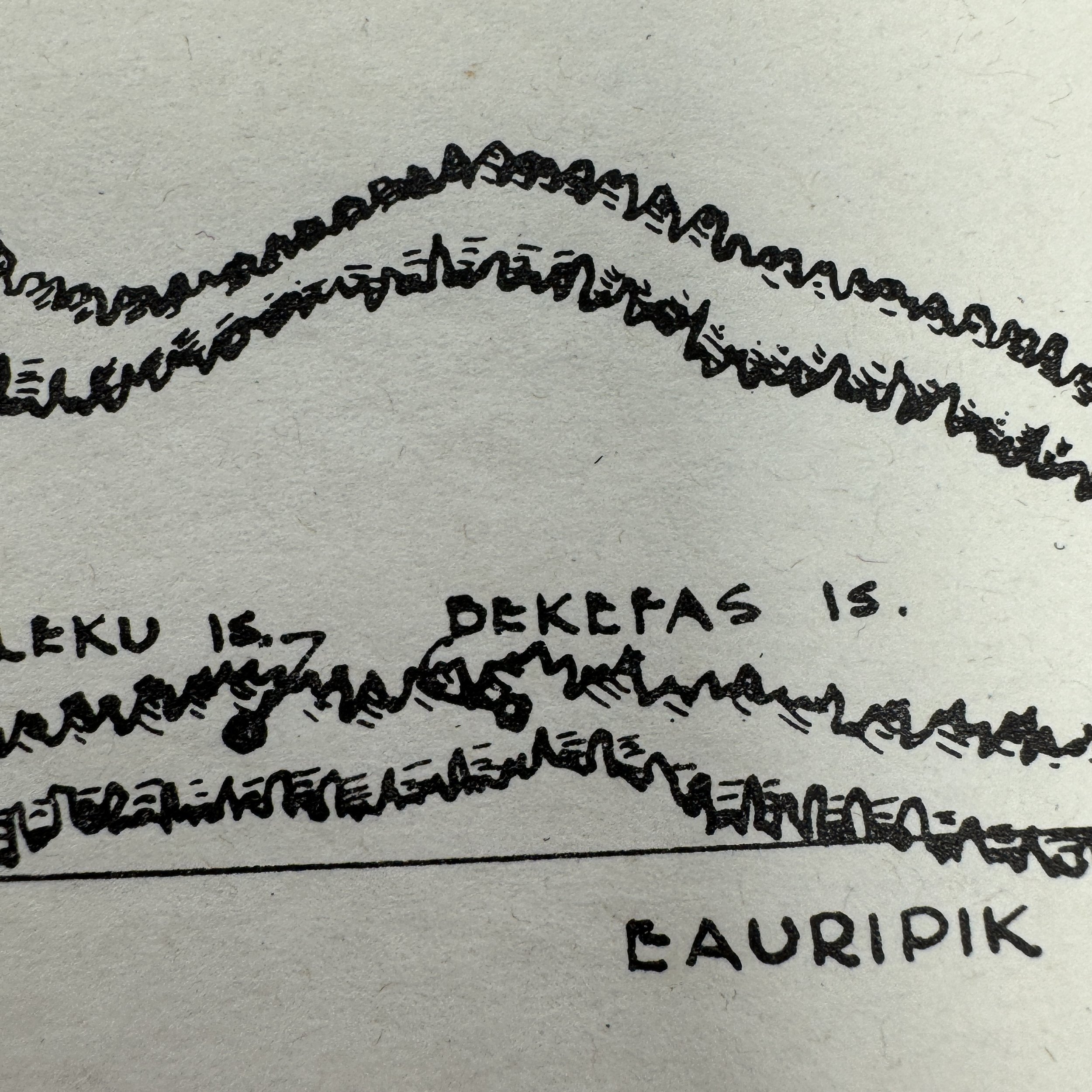

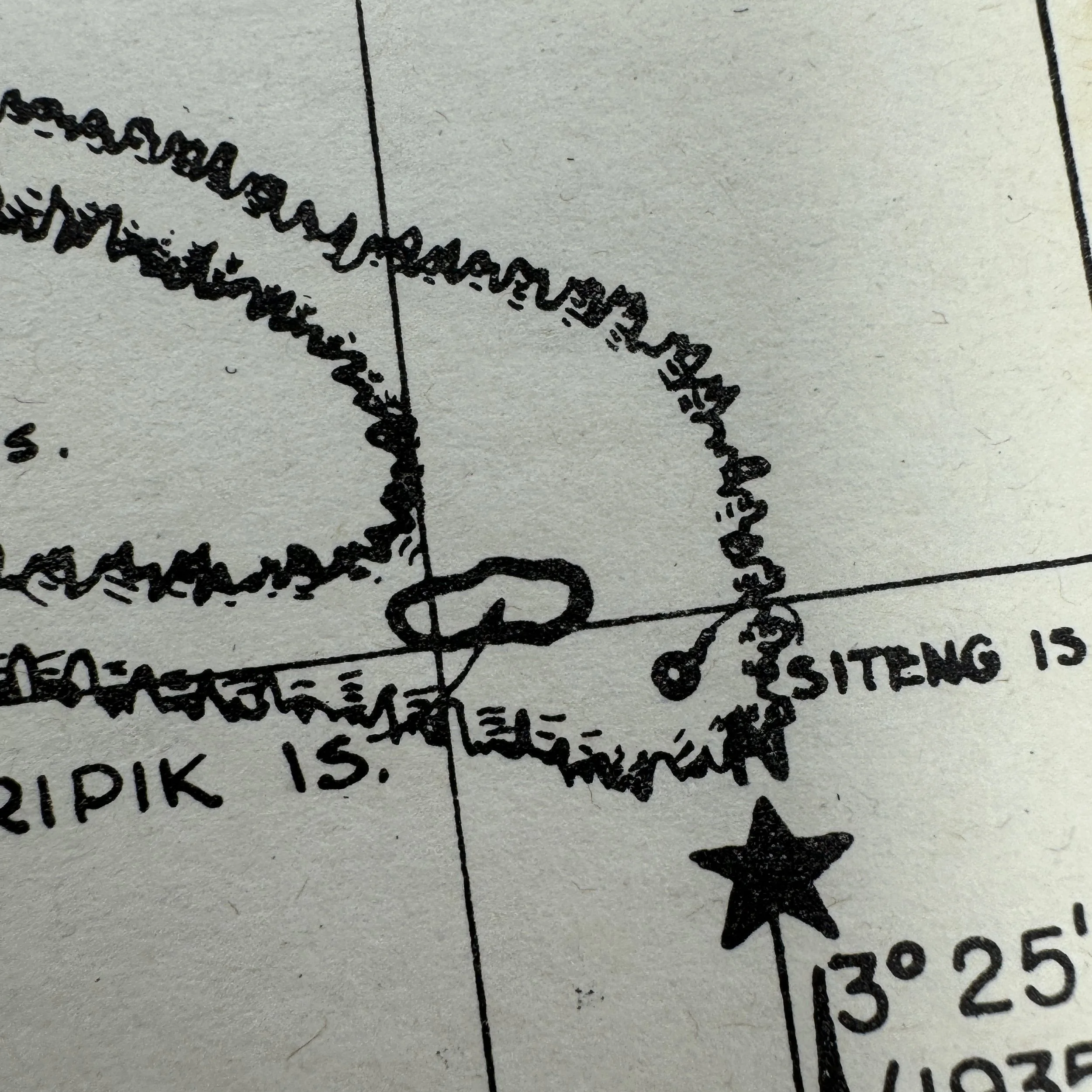

Titled: Eauripik Atoll - Caroline Group

P-51 operations near Eauripik Atoll typically originated from recently captured or newly constructed airfields farther east, such as those in the Marshall Islands (e.g., Kwajalein, Majuro, and Eniwetok). These bases served as springboards for missions stretching hundreds of miles westward into Japanese-held territory. A typical mission would involve meticulous planning: pilots would be briefed on the locations of known or suspected enemy installations, given updated weather reports (which could be treacherous in the vast Pacific), and loaded with a mixture of external fuel tanks, bombs, and ammunition for their .50 caliber machine guns.

Size: 4 × 7 inches

This incredibly rare, museum-grade World War II artifact is an original combat map used by United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) pilots from the Pacific Theater's VII Fighter Command. Known among pilots as the "kneepocket" map, this essential navigation tool was carried by all P-51 Mustang pilots on every combat mission during the war.

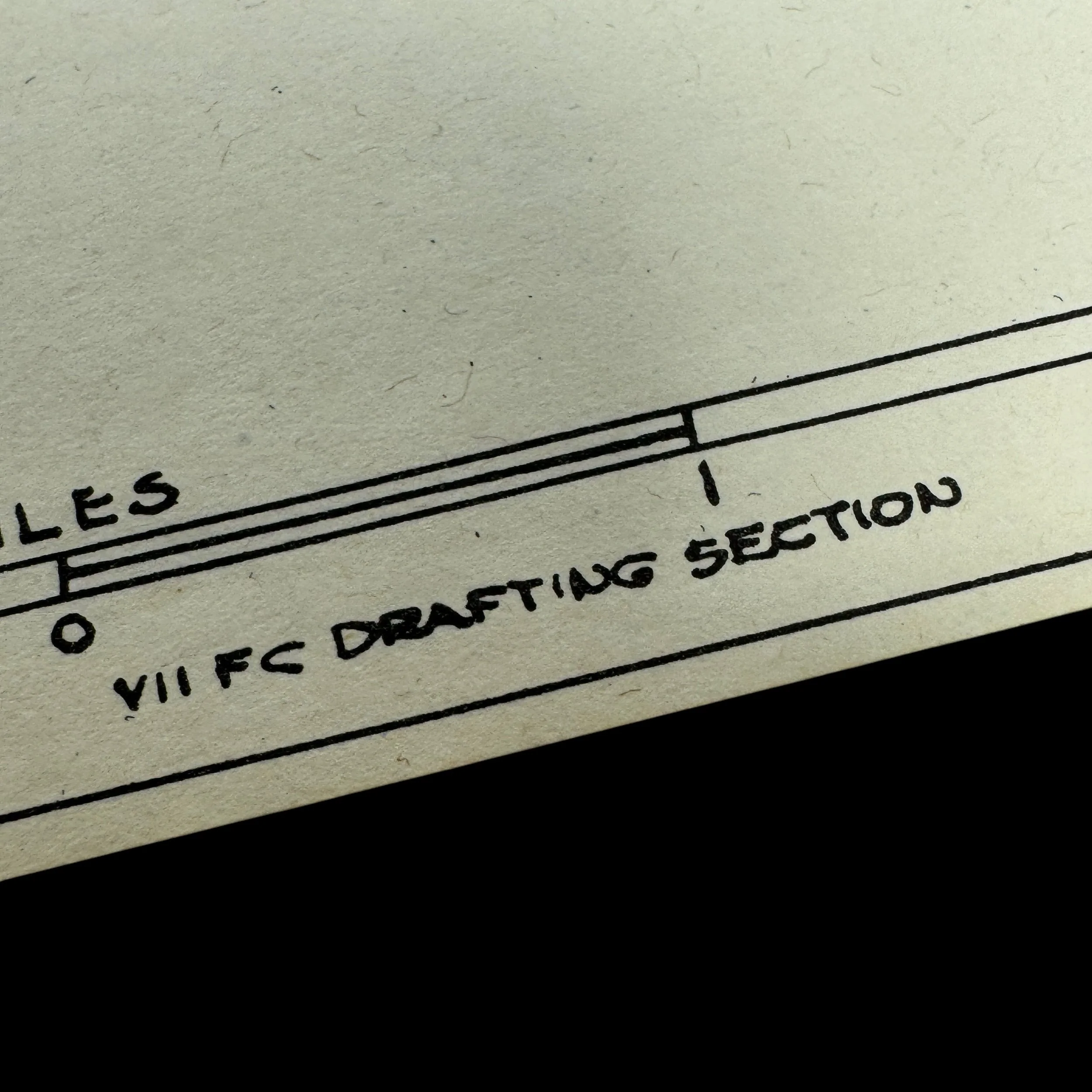

Designed and field-printed by the “VII Fighter Command Drafting Section”, this compact yet detailed map was tailored for the specific challenges faced during long-range escort and reconnaissance missions over the vast Pacific Ocean. It was designed to fit perfectly inside the large knee pocket of a P-51 pilot’s flight suit, ensuring easy access without interfering with cockpit controls during combat missions.

The kneepocket map was vital during missions, whether escorting B-29 Superfortresses on Very Long Range (VLR) bombing runs to Japan, or conducting fighter sweeps and reconnaissance. Pilots used this map while in the air to track their positions, coordinate formation movements, and record real-time intelligence on enemy activity and potential targets.

Additionally, the map played a crucial role in emergency planning, providing vital information about nearby islands for potential crash landings. In a theater where engine failure, damage from enemy fire, or fuel shortages posed constant threats, the kneepocket map could mean the difference between survival and being lost at sea.

As a field-produced document, each map was unique, and only a handful of examples with direct connections to the VII Fighter Command have survived, with most reserved for high-end museum archives. Today, these original VII Fighter Command combat maps are exceedingly rare artifacts of WWII aviation history.

VII Fighter Command Operations Around Eauripik Atoll: P-51 Mustang Missions in the Caroline Islands, 1944–1945

During World War II, the VII Fighter Command played a pivotal yet often underappreciated role in the Pacific Theater, particularly in operations surrounding the Caroline Islands, including the small but strategically located Eauripik Atoll. As part of the broader push across the Central Pacific, VII Fighter Command’s operations in this region in 1944 and 1945 reflected a shift in air combat strategy: from defensive patrols to aggressive long-range offensive missions that aimed to destroy Japanese air power, interdict enemy shipping, and support amphibious landings. While Eauripik Atoll itself was a minor target compared to larger bases like Truk or Yap, its position within the Caroline Group made it a noteworthy waypoint and concern for American forces seeking to neutralize every potential threat to advancing Allied operations. It was here, and across the surrounding seas and skies, that the P-51 Mustang pilots of VII Fighter Command distinguished themselves in extended missions that pushed the limits of aircraft range, endurance, and combat effectiveness.

The VII Fighter Command, originally established in the Hawaiian Islands, underwent a remarkable transformation over the course of the Pacific War. By 1944, under the larger umbrella of the Seventh Air Force, the command had been repositioned forward to support the Central Pacific Drive—an ambitious campaign to capture strategic islands and neutralize Japanese bases, paving the way for future assaults on the Marianas, the Philippines, and ultimately Japan itself. One of the key innovations of VII Fighter Command during this period was the use of long-range fighters—particularly the P-51D Mustang—which, equipped with external fuel tanks, could escort bombers and conduct fighter sweeps over vast stretches of ocean and isolated atolls.

The Caroline Islands, a sprawling archipelago dominated by larger bases like Truk (present-day Chuuk Lagoon), had been fortified heavily by the Japanese as part of their inner defensive perimeter. Smaller atolls like Eauripik, although lacking the massive airfields or ship anchorages of their larger neighbors, still served the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army as observation posts, emergency refueling stops, or points for patrol boats and radio stations. As such, their neutralization was necessary to ensure the safety of American bomber streams and naval forces operating through the region.

Starting in mid-1944, VII Fighter Command’s P-51 squadrons began flying extended-range reconnaissance and fighter-bomber missions over the Caroline Islands. Their objectives were clear: destroy any remaining enemy aircraft, eliminate radar and radio stations, sink coastal shipping and barges, and support the broader effort to isolate and neutralize the Japanese strongholds without the need for costly amphibious invasions. Eauripik Atoll, with its small size and limited infrastructure, was not subjected to the massive bombing raids seen at places like Truk, but it did attract periodic fighter sweeps and strafing attacks from the P-51 pilots tasked with ensuring that no threat remained unchecked.

P-51 operations near Eauripik Atoll typically originated from recently captured or newly constructed airfields farther east, such as those in the Marshall Islands (e.g., Kwajalein, Majuro, and Eniwetok). These bases served as springboards for missions stretching hundreds of miles westward into Japanese-held territory. A typical mission would involve meticulous planning: pilots would be briefed on the locations of known or suspected enemy installations, given updated weather reports (which could be treacherous in the vast Pacific), and loaded with a mixture of external fuel tanks, bombs, and ammunition for their .50 caliber machine guns.

Once airborne, P-51 pilots would form up into flights and proceed westward, often flying at altitudes designed to minimize fuel consumption. Upon nearing their targets, they would jettison empty tanks, descend to low altitude, and begin their attack runs. Against small atolls like Eauripik, attacks typically involved low-level strafing of suspected radio huts, observation posts, and any Japanese personnel sighted along the beaches or inland structures. The P-51s' speed, agility, and devastating firepower made them ideally suited for these "island sweeps," where targets were often fleeting and resistance could vary from nonexistent to surprisingly fierce.

The dangers faced by these pilots were numerous. Beyond the risk of anti-aircraft fire from hidden Japanese gun positions, the sheer distance involved meant that fuel management was critical. Engine trouble, navigational errors, or battle damage could easily result in forced landings at sea—far from friendly forces. While rescue efforts, particularly through the efforts of Navy "Dumbo" rescue flights and submarines, were becoming more effective, a downed pilot in these waters still faced grim odds. Thus, missions to places like Eauripik, though perhaps minor in the grand strategic sense, demanded high levels of skill, courage, and endurance from VII Fighter Command’s P-51 crews.

The broader context of these missions also illuminates their importance. By late 1944 and into 1945, the U.S. Navy's fast carrier task forces were striking deeper into Japanese territory, and Army Air Forces bombers were launching raids that would eventually culminate in the bombing of the Japanese home islands. Ensuring the safety of these operations required a clean sweep of any Japanese outposts that could provide reconnaissance, early warning, or harassment. Even a single radio transmission from a place like Eauripik could compromise an American fleet’s movement or allow for the scrambling of Japanese aircraft from larger bases nearby. Thus, VII Fighter Command's aggressive patrols were not simply "mopping up"; they were a critical component of operational security in the Central Pacific.

Furthermore, the operations of VII Fighter Command helped refine the doctrine of long-range fighter operations that would later be applied on an even greater scale during the air campaigns over Japan itself. The experience gained escorting B-24 Liberators on long missions, conducting island sweeps, and operating with minimal ground-based navigation aids prepared VII Fighter Command’s units for the even more daunting challenges of the final year of the war.

By mid-1945, as the focus of operations shifted farther west toward the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, places like Eauripik Atoll became increasingly irrelevant in a tactical sense, as Japanese forces there were either wiped out or left to wither without resupply. However, the operations carried out by the P-51 pilots of VII Fighter Command in and around such remote points had already achieved their strategic purpose: denying the enemy any foothold from which to threaten the advancing Allied forces.

In sum, the VII Fighter Command’s operations around Eauripik Atoll from 1944 to 1945, though smaller in scale compared to major battles elsewhere, were part of a vital web of missions that showcased the emerging dominance of American air power in the Pacific. The P-51 pilots who flew those dangerous, lonely missions against isolated targets demonstrated not only tactical skill and bravery but also contributed to the greater momentum that was pushing inexorably toward Japan’s ultimate defeat. Their sweeps over tiny atolls like Eauripik symbolized the relentless, island-by-island erosion of Japan’s defensive network—a strategy that would culminate in the final, decisive chapters of World War II.