WWII 1942 D-Day Operation Touch "Charlie Beachheads" Eastern Task Force Amphibious Landing Invasion Map

WWII 1942 D-Day Operation Touch "Charlie Beachheads" Eastern Task Force Amphibious Landing Invasion Map

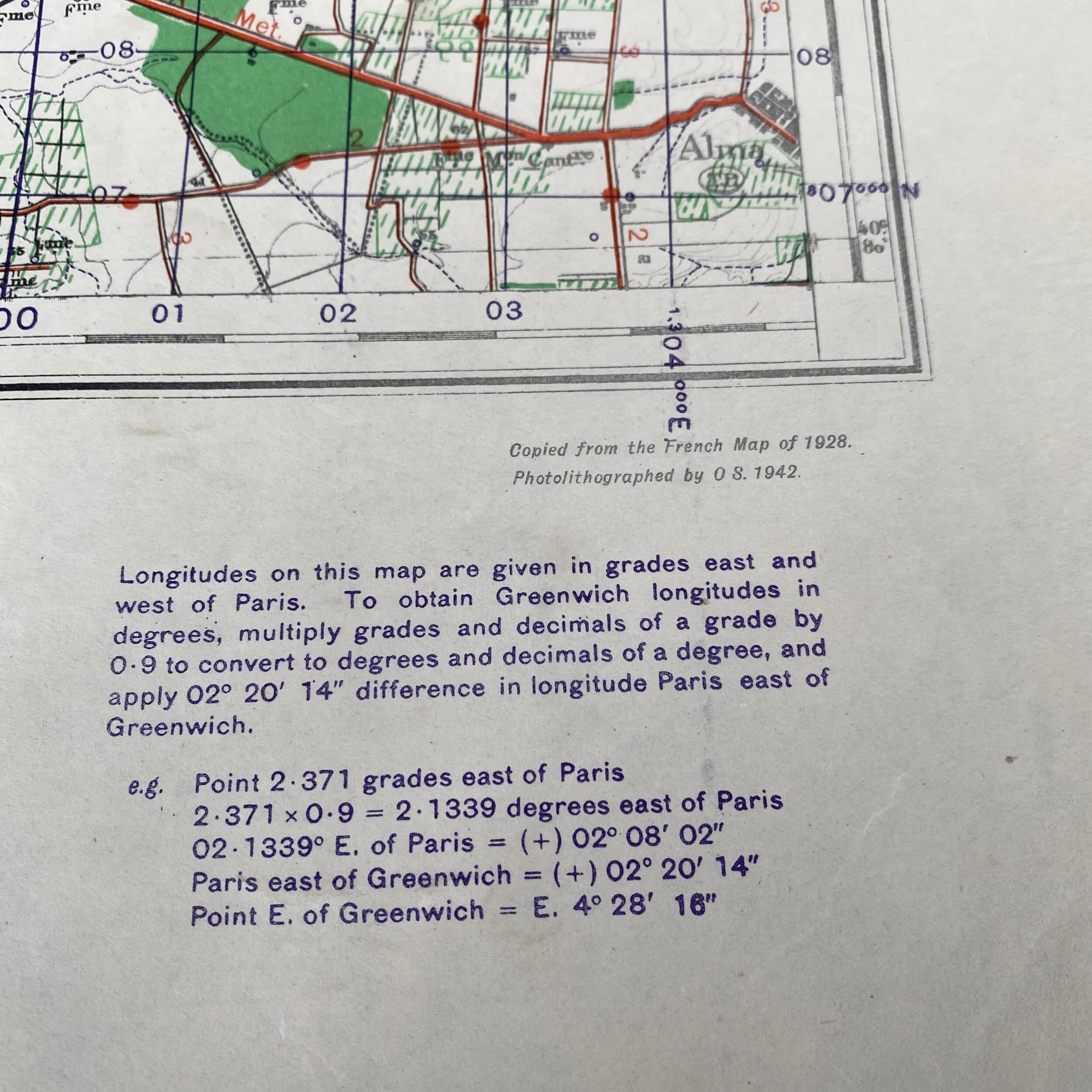

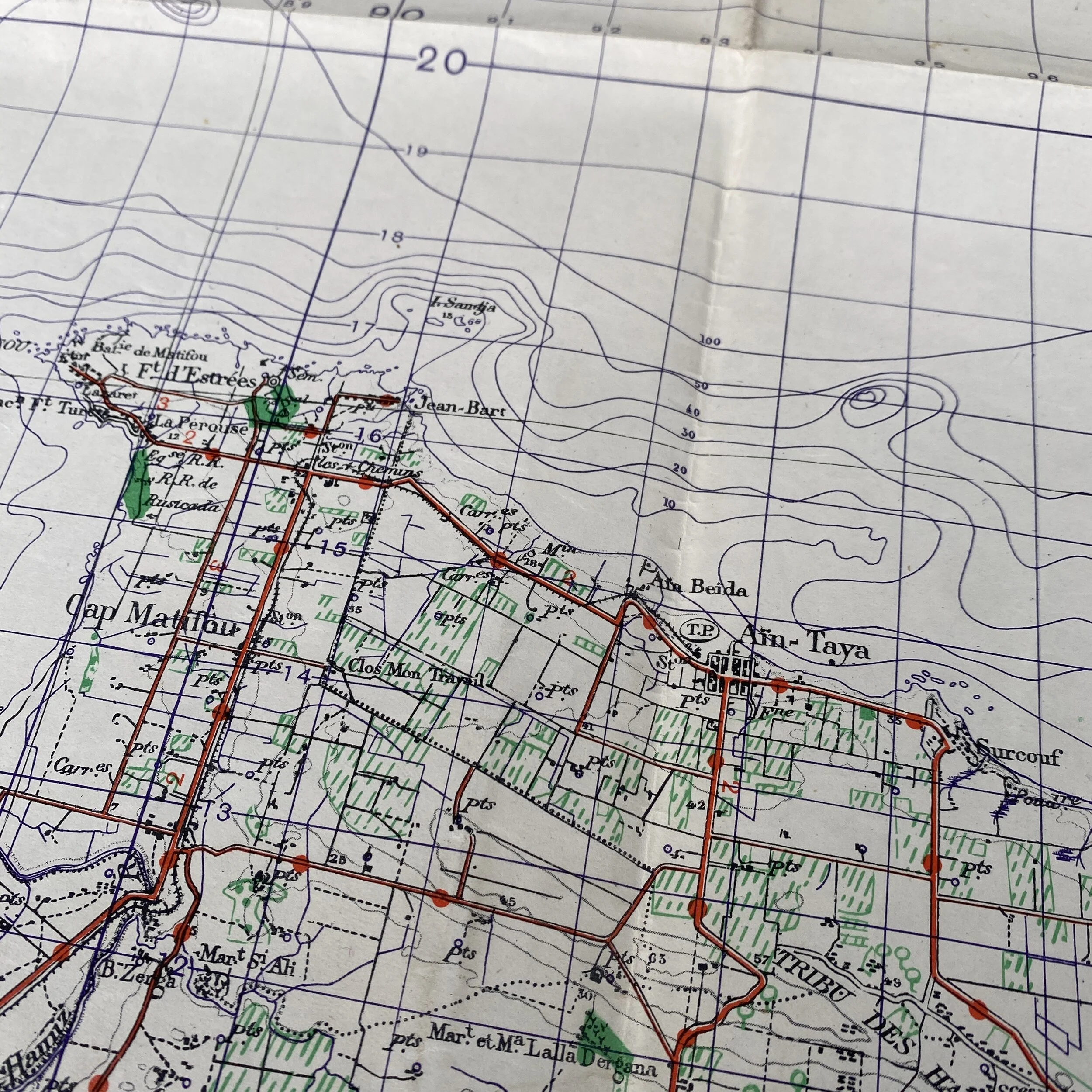

This original ‘SECOND EDITION’ 1942 dated map is titled ‘Alger’ and shows the coastal region of one of the most infamous amphibious landings of Operation Torch. This map shows the amphibious landing beaches designated as “CHARLIE BEACHES” landed on by the 39th Combat Team (9th Division) and Elms Commandos. This map shows CHARLIE RED 1, and CHARLIE RED 2 landed on by the 39th Combat Team whose main targets were to break through Axis beach defenses and assault the towns of Ain Taya and Surcout. Also shown on the map is CHARLIE BLUE and CHARLIE GREEN landed on by the Commandos whose main targets were to break through Axis beach defenses and assault the towns of Ain Taya and sweep the left coastal areas towards Jean-Bart to Batterie De Lazeret.

* Please see below for a full review of the detailed landing/beachheads this map shows.

Operation Torch:

The Allied invasion of French North Africa in November 1942 was intended to draw Axis forces away from the Eastern Front, thus relieving pressure on the hard-pressed Soviet Union. The operation was a compromise between U.S. and British planners as the latter felt that the American-advocated landing in northern Europe was premature and would lead to disaster at this stage of the war.

The operation was planned as a pincer movement, with U.S. landings on Morocco’s Atlantic coast (Western Task Force—Safi, Fedala, Mehdia–Port Lyautey) and Anglo-American landings on Algeria’s Mediterranean coast (Center and Eastern task forces—Oran, Algiers). There was also a battalion-sized airborne landing near Oran with the mission to seize two airfields. The primary objective of the Allied landings was to secure bridgeheads for opening a second front to the rear of German and Italian forces battling the British in Libya and Egypt. However, resistance by the nominally neutral or potentially pro-German Vichy French forces needed to be overcome first.

After a transatlantic crossing, the Western Task Force effected its landings on 8 November. A preliminary naval bombardment had been deemed unnecessary in the vain hope that French forces would not resist. In fact, the initially stiff French defense caused losses among the landing forces. However, by 10 November, all landing objectives had been accomplished and U.S. units were poised to assault Casablanca, whose harbor approaches were the scene of a brief, but fierce, naval engagement. The French surrendered the city before an all-out attack was launched.

The Center Task Force, composed from assets based in the United Kingdom, also encountered resistance by French shore batteries and ground forces to its 8 November landings. Vichy French warships undertook a sortie from Oran’s port, but were all either sunk or driven ashore. After an attempt to capture the port facilities failed, heavy British naval gunfire brought about Oran’s surrender on 9 November.

Operations of the Eastern Task Force (also arriving from Britain) were aided by an anti-Vichy coup that took place in Algiers on 8 November. Thus, the level of French opposition at the landing beaches was low or non-existent. The only serious fighting took part in the port, where U.S. Army Rangers were landed to prevent the French from destroying facilities and scuttling ships. Resistance had been overcome by the evening of 10 November, when the city was surrendered to the U.S. and British forces.

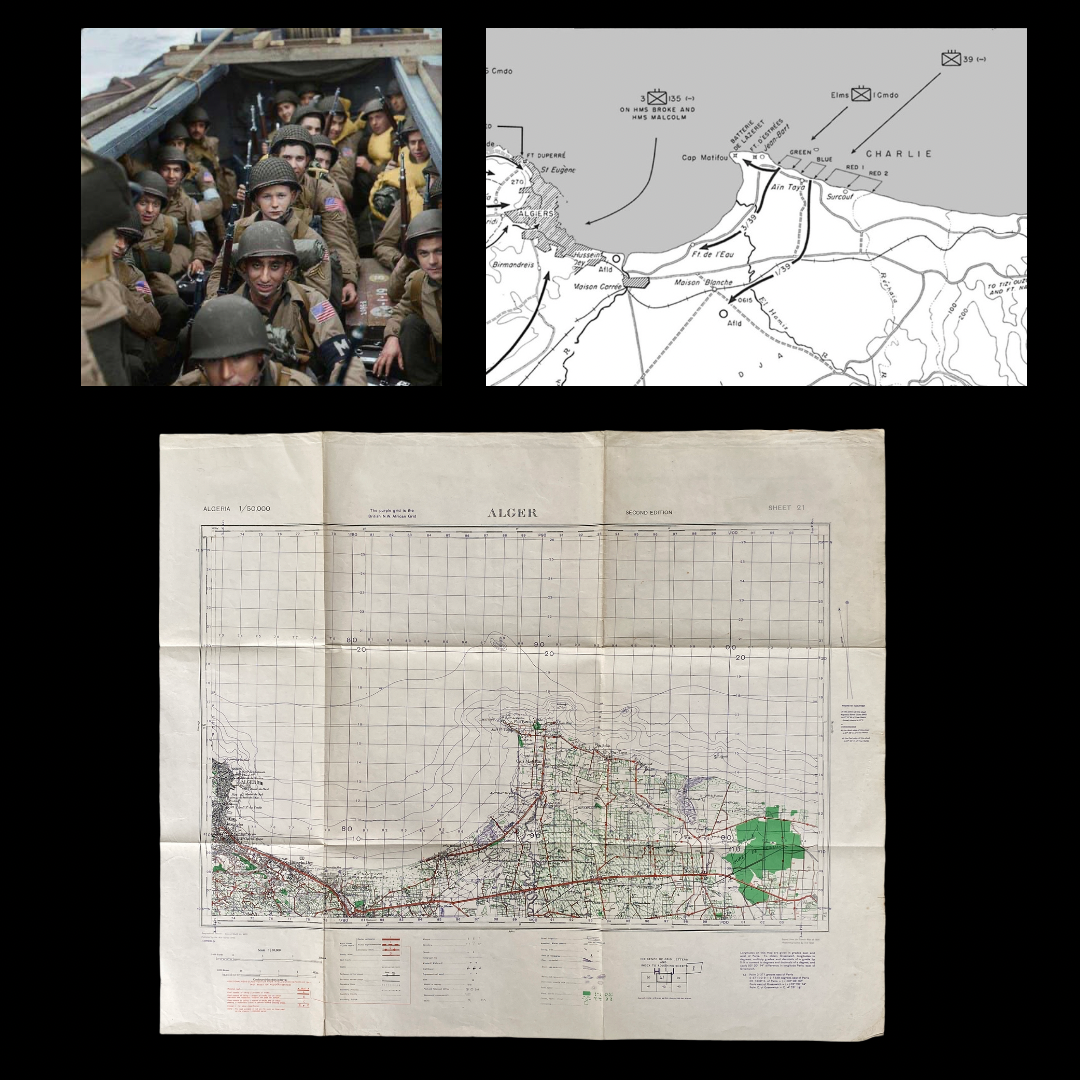

U.S. TROOPS LANDING NEAR SURCOUF, 8 November 1942:

Team of 5,688 officers and enlisted men, reinforced by 312 (198 British, 114 American) from the 1st Commando, all under the command of Col. Benjamin F. Caffey, Jr. They were transported by the American combat loaders Samuel Chase (the command ship), Leedstown, Almaack, and Exceller, under escort by three British warships. The senior naval officer, landings was Capt. Campbell D. Edgar (USN). Beach parties and signal sections were American, augmented by British Army beach signal units. More than an hour before midnight, the small convoy established communications with the beacon submarine and hove to some eight miles offshore. The transports had started on this journey from New York Port of Embarkation on 25 September only a short time after most of them had been commissioned. The unfortunate Thomas Stone was the best prepared for night amphibious operations.29 The convoy began its actual assault operations, therefore, under the handicap of inexperience and insufficient training, and under the additional difficulty of last-minute adjustments arising from the loss of the Thomas Stone.

In a moderate swell and under a clear sky, with lights ashore undimmed and the piloting party waiting to guide the landing craft formations to the beaches, the disembarkation into the boats began. The difficulties which delayed other combat teams, whether in the Western, Center, or Eastern Task Forces, in getting assault waves in place to start their runs to shore were also experienced in the Charlie Sector. But energetic action and skillful improvisations overcame those difficulties in time to make the initial touchdowns at about 0130 at all but one point.

The 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, and supporting units were on the Samuel Chase; the 3d Battalion and a detachment of the 1st Commando (five troops only) were on the Leedstown. The Almaack carried the Headquarters Company and vehicles, most of the drivers of which were on the Exceller or scattered on the other ships. The 3d Battalion, originally scheduled for the reserve, was now to undertake the mission for which the luckless 2d Battalion on the Thomas Stone had been preparing up to a few hours earlier.

Of four beaches which had been designated in the sector, three were employed. Charlie GREEN extended for about 800 yards, halfway between the villages of Jean-Bart and Aïn Taya. Charlie BLUE, of the same length, lay directly in front of Aïn Taya. RED Beach, subdivided into RED 1 and RED 2, reached from the hamlet of Surcouf, east of Aïn Taya, to the marshy mouth of the Rérhaïa river. The landing schedule, adjusted at a conference of commanders on the Samuel Chase to meet prevailing conditions, provided that the 1st Battalion Landing Team should go to Charlie BLUE, and Commandos and the 3d Battalion Landing Team should go to Charlie GREEN, and service units and vehicles should use Charlie RED, the only one which had easy access to the interior.31 The others were faced by an almost vertical bluff with stairs for pedestrians but with no good exits for vehicles.

As the assault waves were nearing the beaches, two ships of the slower convoy with matériel for the easternmost landings arrived in the transport area, and, since no opposition appeared to be coming from ashore, Captain Edgar ordered all his transports to proceed closer to the beaches. About 0130, they started to positions only 4,000 yards out. More than an hour later the battery on Cap Matifou was roused. Even before Captain Edgar had received a report from the beachmaster, he heard a broadcast from Washington announcing that the landings under his command had been successfully accomplished.32

Searchlights on Cap Matifou swept over the area, illuminating not only the transports but the British destroyers, Cowdray and Zetland. The four big guns of the Batterie du Lazaret directed several shells toward the destroyers, which fired in return, dousing the light and forcing the battery to suspend fire.33

The westernmost landings in the Charlie Sector were the last to be made, for the Commandos in eleven LCP's, guided by a pilot aboard one of these boats, after a late start from the vicinity of the Leedstown ran into an offshore fog bank, slowed down to enable the formation to keep together more closely, and completed their run to GREEN Beach about two hours behind schedule.

The first waves of infantry from the Samuel Chase, and the service units from the Almaack, bound for BLUE and RED Beaches, were expected to leave together at the same time as the Commandos. They were to have a motor launch and pilot at both outside front positions, and to remain together for the first six miles until they arrived at an offshore obstacle and landmark, the Bordelaise Rock. The last 2,000 yards would find the two groups diverging to their respective objectives. Unfortunately for the execution of this plan, the navigators of the landing craft going to RED Beach failed to swing southeastward at the rock and continued instead to BLUE Beach.34 A few boats bound for GREEN Beach from the Leedstown also strayed into the BLUE Beach area. Yet in the absence of resistance, it was possible for the units to straighten out the situation quickly. The 1st Battalion Landing Team (Lt. Col. A. H. Rosenfeld) at Aïn Taya was beginning to reorganize by 0130, and the 3d Battalion Landing Team (Maj. Farrar O. Griggs) nearer Jean-Bart was about fifteen minutes later in preparing for its inland advance.35

The Commando troops under command of Maj, K. R. S. Trevor (Br.) moved westward along the coastal road. Detachments soon controlled three important objectives: Jean-Bart, a signal station and barracks near Fort d'Estrées, and the approaches to the Batterie du Lazaret. The battery and fort declined to surrender or to accept a truce, and proved too strong to be taken by assault with the means available. A request was made, therefore, for heavy supporting naval gunfire.36

The 3d Battalion, 39th Infantry, was expected to move by the coastal road to Fort de l'Eau, Maison Carrée, and Husseïn Dey. Here it was to seize a small airfield and subsequently establish contact with the Allied forces approaching Algiers from the west, with the special detachment which was to have stormed Algiers Harbor, and with the friendly French who were to have gained control of the city.37 A march of approximately six miles brought the 3d Battalion to the resort village of Fort de l'Eau, where French troops disputed its further westward progress. Three French tanks supporting the infantry there damaged some American trucks, threatened to strike the battalion on the flank, and brought the advance toward Algiers to a stop.38

The 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, had the vital mission of seizing the Maison Blanche airdrome before daylight. Beach conditions immobilized the newly landed antitank guns and 105-mm. howitzers, but advance elements set off without them. The battalion made an expeditious approach march by road for most of the ten miles to the airfield, arriving at its objective at approximately 0615.39 A few French tanks, against which the attacking force had no suitable weapons, were encountered as the battalion neared the airfield, but after they had fired briefly as if in merely token resistance, they withdrew while the American troops occupied the airfield. Negotiations for its surrender were completed by 0830.40 Fog over the airdrome was too thick to permit immediate use by Royal Air Force units, but the 43d Squadron (eighteen Hurricanes) was reported in at 1035, with two other units then summoned arriving during the afternoon. The main problem in using the field was to obtain fuel and maintenance, but enough fuel was found to get some of the aircraft aloft over Algiers and Cap Matifou before sunset.41

Capture of the field proved far less advantageous than had been anticipated, for vehicles, supplies, and ground crews for the Royal Air Force squadrons, brought to the sector on the cargo ships Dempo, Macharda, Maron, and Ocean Rider, had met with ill fortune. The high swell and surf through which the landings of the assault troops were made demanded a proficiency in small-boat navigation exceeding that of most of the half-trained crews assigned to that duty. As the craft piled up on the beaches, or swamped offshore, the rate of debarkation by later serials slowed down sharply. The weather, moreover, deteriorated during the day, also helping to prevent aviation supplies sorely required at Maison Blanche from being landed. The carrier aircraft continued to furnish almost all air support on D Day and to defend the port.42 The defense of the airfield was entrusted to Company A, 39th Infantry, reinforced by an extra machine gun platoon from Company D and by a section of 81-mm. mortars, while the remainder of the 1st Battalion occupied an area north and northeast of the field.43

While the approach to the city from the east was being held up on Cap Matifou and at the village of Fort de l'Eau, and while rough water was destroying more and more landing craft, slowing down the movement of men and supplies from ship to shore to a mere trickle, efforts were made to break the deadlock at the Batterie du Lazaret. The request for naval gunfire in support of the Commando troops on Cap Matifou brought at 1040 a bombardment from H.M.S. Zetland which continued for an hour but which proved insufficient to produce surrender.44 A combined air and naval bombardment was therefore delivered early in the afternoon. While the Commandos pulled back a second time, the cruiser Bermuda and a flight of Albacore dive bombers from the carrier Formidable struck the area under attack for more than an hour, commencing about 1430. After 1600, the Commandos, supported by one self-propelled 105-mm. howitzer, renewed their attack on the battery. Some fifty French marines surrendered at 1700. Reinforced by two armored cars, the Commandos went on to attack Fort d'Estrées about half an hour later, but without success. At 2000, the attack was broken off. The Commandos withdrew to the south for the remainder of the night.45

Axis bombers arrived at dusk to hinder Allied progress toward the seizure of Algiers. One small flight demonstrated without serious effect near Algiers, and another achieved a preliminary success on the eastern side of Cap Matifou against the ship anchored off Charlie Sector. They severely damaged the destroyer Cowdray and immobilized the transport Leedstown with a hit astern. After narrow escapes other vessels shifted next morning to the bay of Algiers for unloading in Algiers Harbor. The Leedstown was left behind, a setup for return visits on 9 November, when two afternoon attacks forced its abandonment. U.S. Navy losses on the ship were eight dead and fourteen wounded. Army personnel also suffered casualties while trying, with the assistance of those already on the beach, to reach land through surf and undertow.