VERY RARE! WWII Original Battle of the Bulge Patton & Montgomery U.S. Infantry & Armored Combat Map

VERY RARE! WWII Original Battle of the Bulge Patton & Montgomery U.S. Infantry & Armored Combat Map

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

“Middleton’s troops were to jump off from their positions around Bastogne, move west of that town, then northeast to Houffalize. The corps, which comprised about 90,000 men, was made up of one combat command of the 10th Armored Division, the 11th Armored Division, the 17th and 101st Airborne Division, and the 87th Infantry Division.”

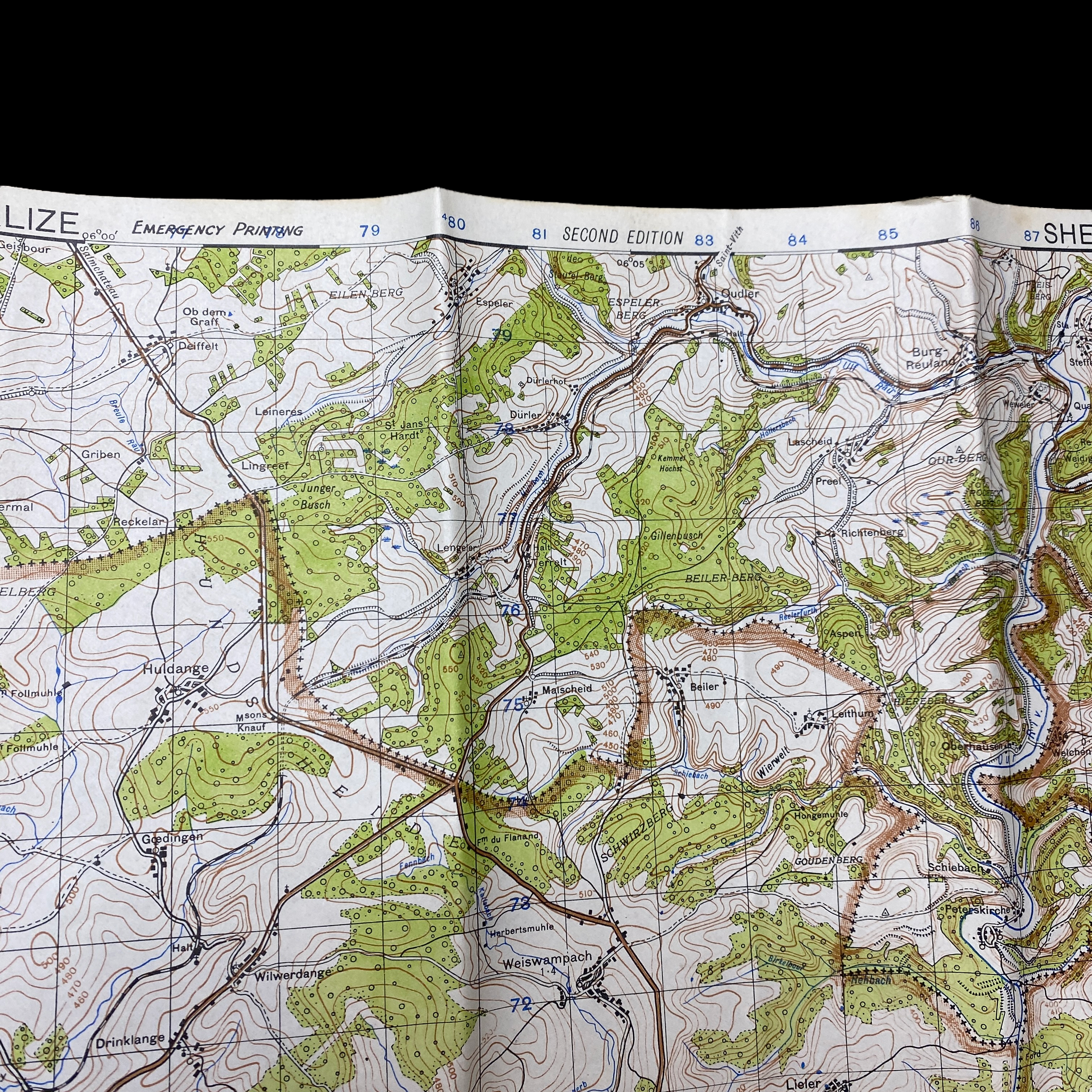

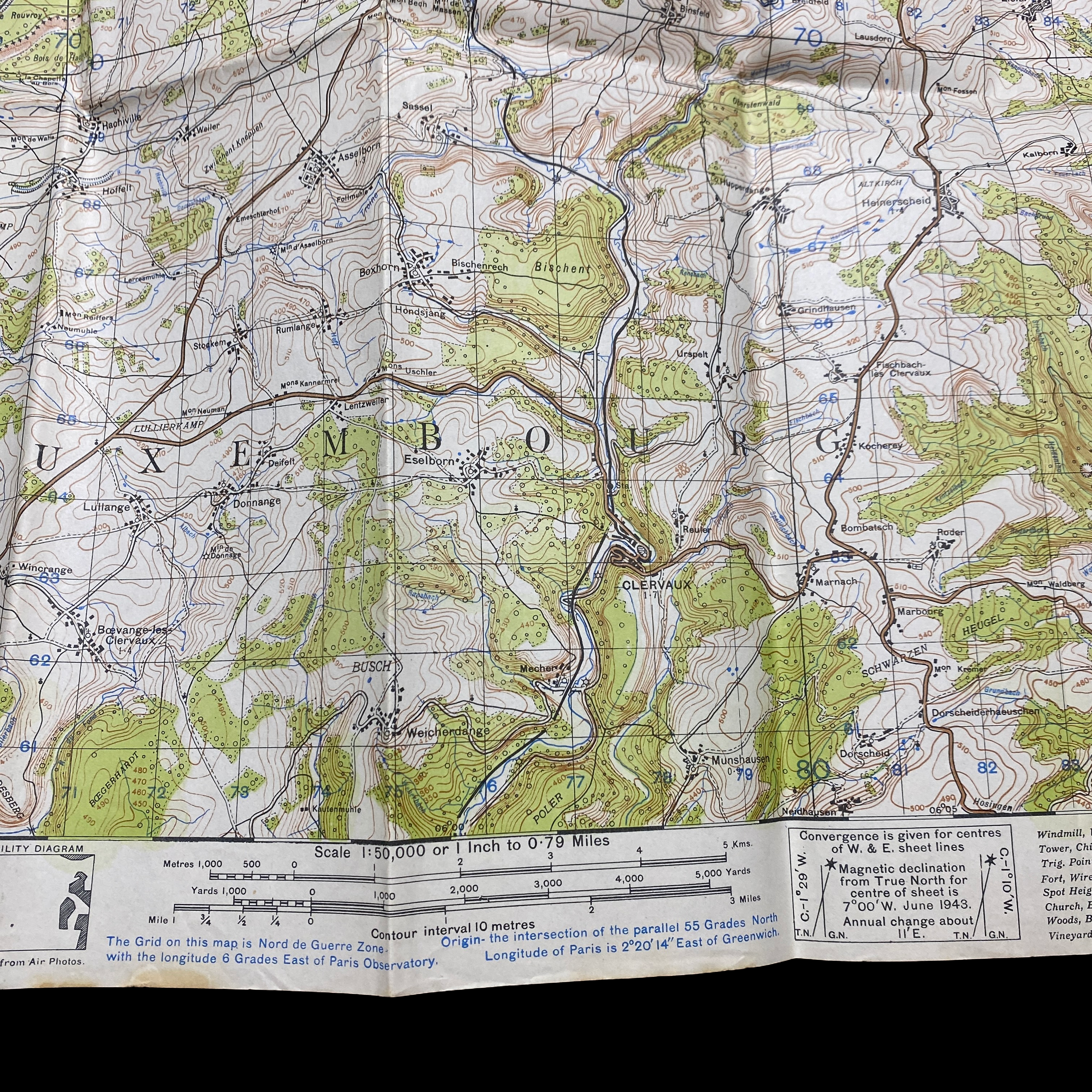

This incredibly rare and museum-grade WWII map titled “HOUFFALIZE” was a very scarce “EMERGENCY PRINTING” used during the infamous Battle of the Bugle. Houffalize is a small town located just nine miles northeast of Bastogne. Houffalize was one of the strategical turning points of the Battle of the Bugle as it is where Generals Montgomery and Patton met up in a counter-attack against remaining German forces! This combat operations map was used by infantry and armoured divisions around Houffalize during the Battle of the Bugle.

While the German offensive had ground to a halt during January 1945, they still controlled a dangerous salient in the Allied line. Patton's Third Army in the south, centered around Bastogne, would attack north, Montgomery's forces in the north would strike south, and the two forces planned to meet at Houffalize.

Assigned to carry the weight of the attack for Third Army was Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton’s VIII Corps, part of the First Army, but for command and control purposes serving under Third Army. Middleton’s troops were to jump off from their positions around Bastogne, move west of that town, then northeast to Houffalize. The corps, which comprised about 90,000 men, was made up of one combat command of the 10th Armored Division, the 11th Armored Division, the 17th and 101st Airborne Division, and the 87th Infantry Division.

First Army’s main effort would be made by its VII Corps under Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins. Heavily reinforced and approaching 100,000 men, VII Corps included the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions; the 83rd, 84th, and 75th Infantry Divisions; and 12 independent artillery battalions. Starting from the Hotton-Ourthe River area across the Bastogne-Liege highway, it was to advance southeast between the Ourthe and Lienne Rivers to take the high marshland of the Plateau des Tailles, which commanded the town of Houffalize 12 miles away.

The standoff in the Ardennes abruptly ended with a renewed German push against Bastogne. While the front remained quiet in the north, between January 2 and 4 repeated attacks were delivered by the Wehrmacht on the American-held bastion in the south. Under a hail of concentrated U.S. artillery fire in conjunction with American III Corps counterattacks, the Nazis were stopped cold. This proved to be the final German offensive effort in the Battle of the Bulge. Concluding that the enemy’s attacking power was spent, Montgomery ordered the First and Third Armies to commence their attack toward Houffalize on January 3.

From January 3 through 14, the American northern and southern strike forces edged toward Houffalize. The going was tough. The Ardennes proved to be a natural military obstacle, easy to defend and murderous to attack. They not only had to face a determined and enterprising foe, but also freezing weather, severe icy conditions, snow to depths of up to two feet, dense pine forests, deeply cut ravines, steep cliff-like ridges, and swift streams.

Heavy Losses From the German Infantry & Panzer Formations:"

Compounding the extremely difficult geography was a general lack of roads in the region. Road movement was critical, especially in First Army’s area of operations. Only one major road, the Liege-Houffalize-Bastogne highway, led directly to the objective. A network of secondary roads and tracks intersecting with numerous villages, bridges, defiles, and hairpin curves would have to be navigated in the face of enemy opposition. The conditions were miserable for both armored and nonarmored vehicles, requiring that the infantry often take the lead and engage the enemy alone since the tanks and assault vehicles could not freely maneuver in the wilderness. Additionally, overcast conditions decreased visibility to the extent that close air support and artillery were never assured.

Facing the two American drives toward Houffalize was a mixture of German infantry and panzer formations. These were mere shells of their former selves after the ferocious fighting they had been through during the past weeks. Strengths in the infantry divisions varied from 1,500 to 2,500 men, and there were around 5,000 to 6,000 personnel in the panzer units. Losses had been so high and maintenance so difficult that a German armored division counted itself lucky to have 30 fighting vehicles operational at any given time.

The Waffen SS panzer divisions of Sixth Panzer Army, fronting the northern part of the Bulge, had either been shifted to the Bastogne sector by mid-January or pulled back behind St. Vith to guard against an attack near the base of the original German penetration. This left only understrength formations, including the 560th Volksgrenadier Infantry Division and the 116th Panzer Division to face the American onslaught from the north. Fearing an imminent collapse of that face of the salient and the potential entrapment of German troops at the most distant penetration of the Bulge, the commander of the Fifth Panzer Army, General Hasso von Manteuffel, requested an immediate pullback to a line anchored on Houffalize. His plea was not granted until January 8, and then only to the extent that the tip of the Bulge was evacuated.

The snail-like pace of the northern and southern thrusts to Houffalize continued through the 14th, hampered by snow-storms and clever German resistance centered on the use of minefields and ambushes abetted by counterattacks employing small groups of mixed infantry, armored, and antitank forces. On the 14th, Hitler was finally persuaded to allow a withdrawal of his army to the high ground just east of Houffalize, extending northward behind the Salm River and southward through existing positions east of Bastogne. On January 15, an advance guard of the 101st Airborne entered the village of Norville five miles south of Houffalize.

“When Houffalize is taken, we will have a junction between the First and Third Armies, which will put Bradley back in command of the First Army. This will be very advantageous, as Bradley is much less timid than Montgomery.” Thus wrote George Patton in his diary on the night of January 12, 1945. In the same entry, he noted that VII and VIII Corps should be in Houffalize by the next day, “as there is not much in the way.”

Major Michael Greene Asked to Lead the Operation:

The Third Army chief was mistaken; January 13 came and went with the main concentration of VIII Corps seven miles from the town. Notified that elements of the First Army were just west of Houffalize on the banks of the Ourthe River, Patton determined to take it by pushing a flying column of Third Army troops north. The move would not only give his command credit for the amputation of the German bulge, but would also deprive Montgomery of the honor. To Patton, the feat would be a repeat of the race to Messina 17 months before. There, to Montgomery’s profound chagrin, the Americans under Patton beat the British to that city, signaling the end of the campaign for Sicily.

Patton gave the task of taking Houffalize to Brig. Gen. Charles S. Kilbrun’s 11th Armored Division and, via the fortunes of war, Major Michael J.L. Greene was tapped to lead the operation. Greene was a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy class of 1941. Before being assigned to the 11th Armored, he had served in the 2nd and 7th Armored Divisions, rising from platoon to squadron leader. After attending the Command and General Staff College in 1943, the 26-year-old was posted to the 41st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron of the 11th Armored Division as its executive officer.

On January 15, the 41st, commanded by Lt Col. H.M. Foy, was attached to the 11th Armored Division’s Combat Command A and deployed along the northern fringe of the Les Assins Woods near the village of Monaville, Belgium. At 11 am on the 15th, the squadron, made up of Troops A, C, D, and E supported by the 16 Stuart light tanks of Company F, was ordered to hand over responsibility for its sector to the 17th Airborne Division and move to Monaville and then north and east to Bertogne. The squadron protected the left flank of Combat Command A’s eastward advance along the line Pied Du Mont Woods-Comogne-Rastadt-Velleroux. When Greene reached Bertogne with most of the unit in tow during midafternoon, he discovered Colonel Foy had gone forward with Troop C, leaving Greene in command of the bulk of the squadron.

No sooner had Greene reached the town than the commanding officer of Combat Command A, Brig. Gen. W.A. Holbrook, Jr., accompanied by the division chief of staff, Colonel J.J.B. Williams, drove into the village looking for Colonel Foy. Greene reported that Foy was not in town.

General Holbrook looked at the major and said, “Okay. We have another mission that you and the remainder of the squadron must undertake. This is an extremely important mission, a must, directed by the army commander.” He went on to say, “We must get to Houffalize tonight and contact the First Army as it comes down from the north.”

Colonel Williams then spoke up and in a grave voice told Greene, “This is a difficult assignment for anyone because Houffalize is at least 10 miles behind German lines. But someone must get through to establish contact with the 2nd Armored Division as it comes down from Achouffe. They may be already there. General Patton wants this mission accomplished without delay, and he wants this division [11th Armored] to do it.”

Green’s Deliberating Mind Raced at a Mile a Minute:

Holbrook broke in at this point with a wave of his hand and the comment, “Here is an excellent reconnaissance squadron mission. We’ve got to get around to the northern flank of the division and then through the German lines if they extend that far. It should be interesting.”

Greene showed no emotion as the other two officers spoke, but his mind was going a mile a minute. He knew that the approaches to Houffalize, except by way of the main highway, were indistinct snow-covered trails meandering through dark woods—woods that would become a lot darker as night neared. Putting such thoughts aside, Greene ordered the squadron operations officer to round up any tanks and assault guns available and put D Troop on alert to move out immediately.

The major then began to study maps of the area and plan the details of the operation. Not long afterward, Colonel Foy joined the group of officers pouring over the maps in the squadron command post. Foy formally put Greene in charge of the force heading into Houffalize.

Greene’s ad hoc strike force consisted of Troops D and E, the 2nd Platoon of Troop A, and the light tanks of Company F, the latter unit under Captain Harold Mullins. The last two units were on outpost duty beyond the town of Bertogne, so they were radioed to meet Troops D and E outside the village of Rastadt, two miles from Bertogne, as soon as possible. Riding in his half-track behind the last vehicle of the point, Greene led his small, lightly armed command, consisting of 17 M5 light tanks, 15 M8 Greyhound armored cars, six assault guns, 15 jeeps, and six M3 halftracks with 450 men, out of Bertogne at 5:30 pm.