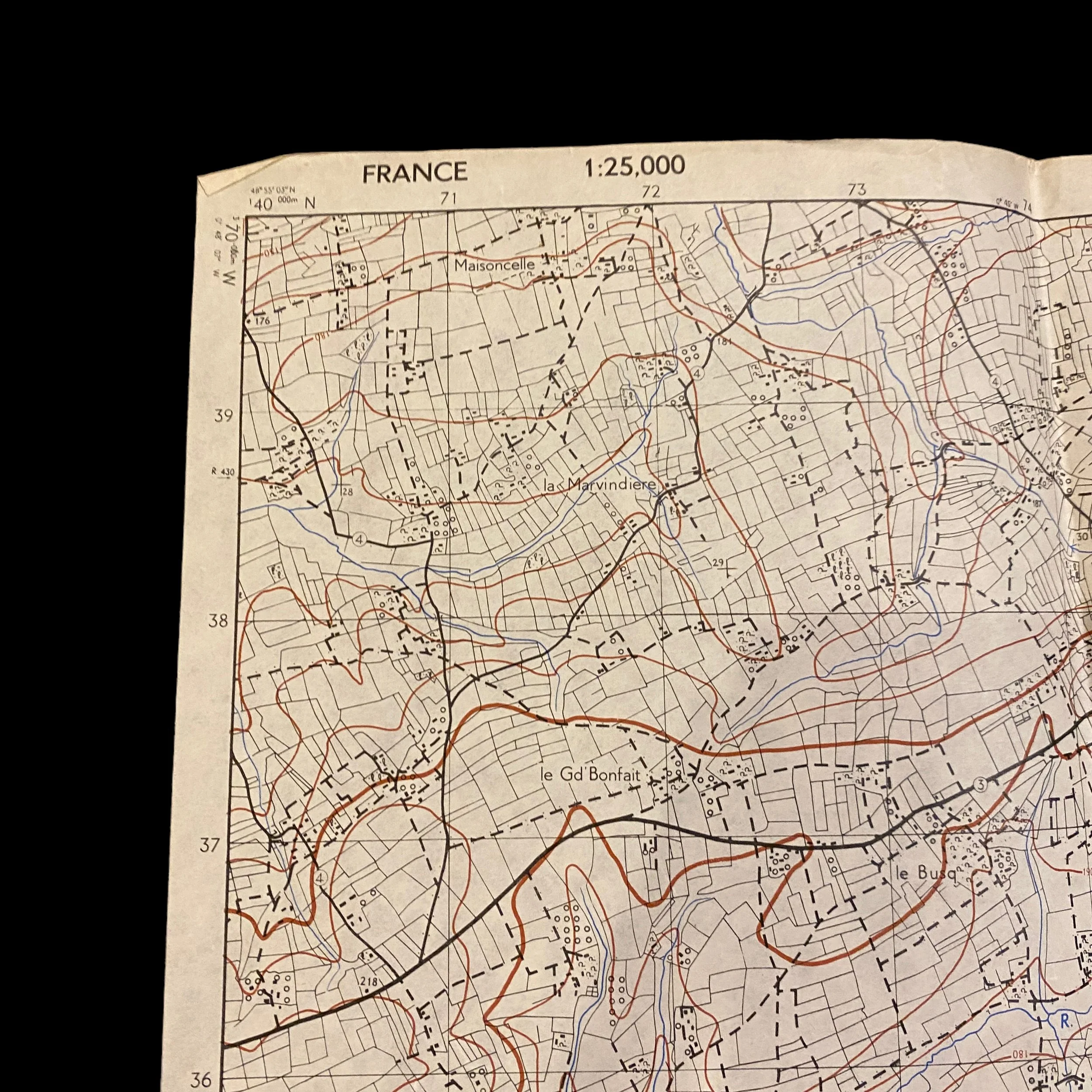

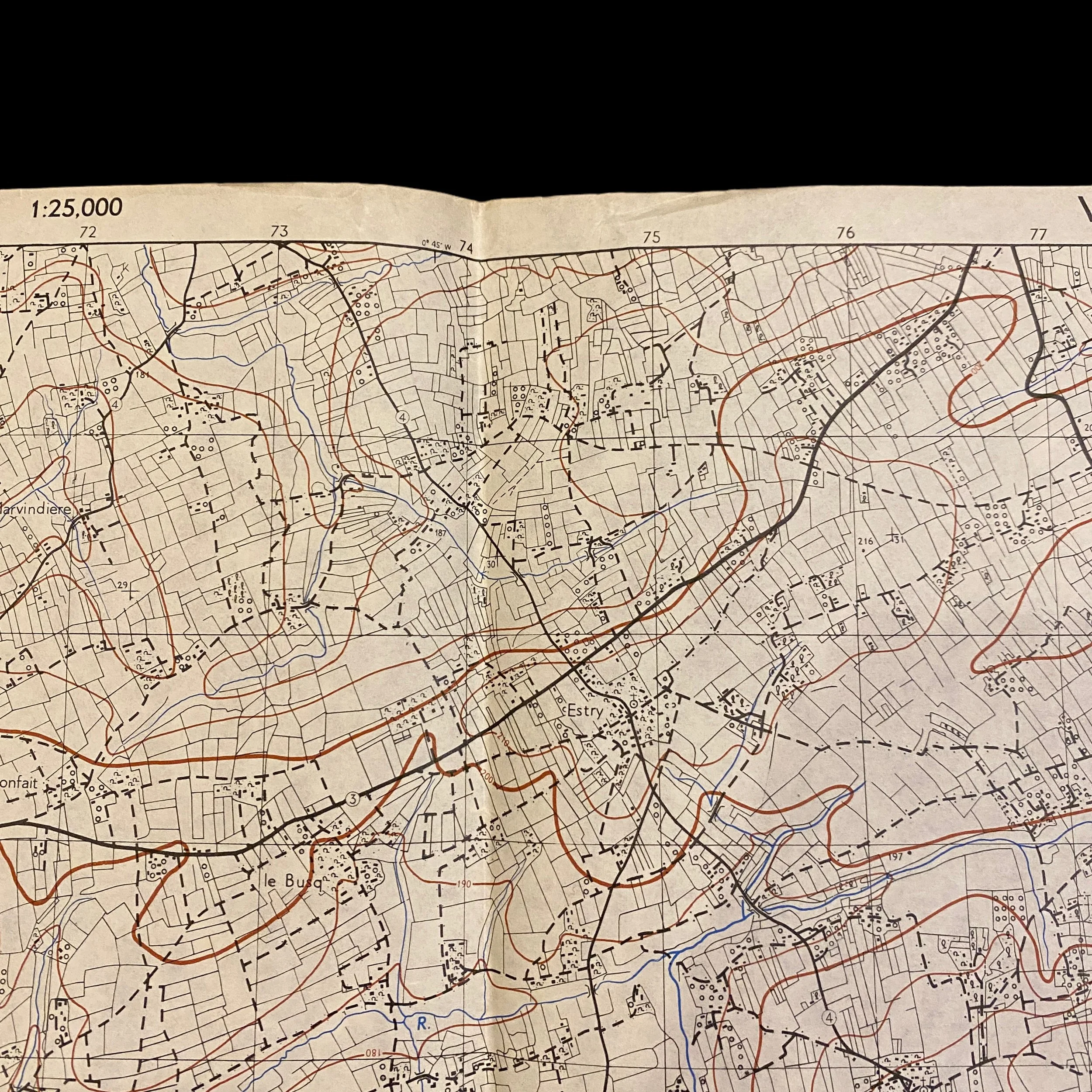

RARE! WWII 1944 D-Day Invasion of Normandy "Breakout of Omaha" VASSY - NORMANDY, FRANCE Combat Assault Map

RARE! WWII 1944 D-Day Invasion of Normandy "Breakout of Omaha" VASSY - NORMANDY, FRANCE Combat Assault Map

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

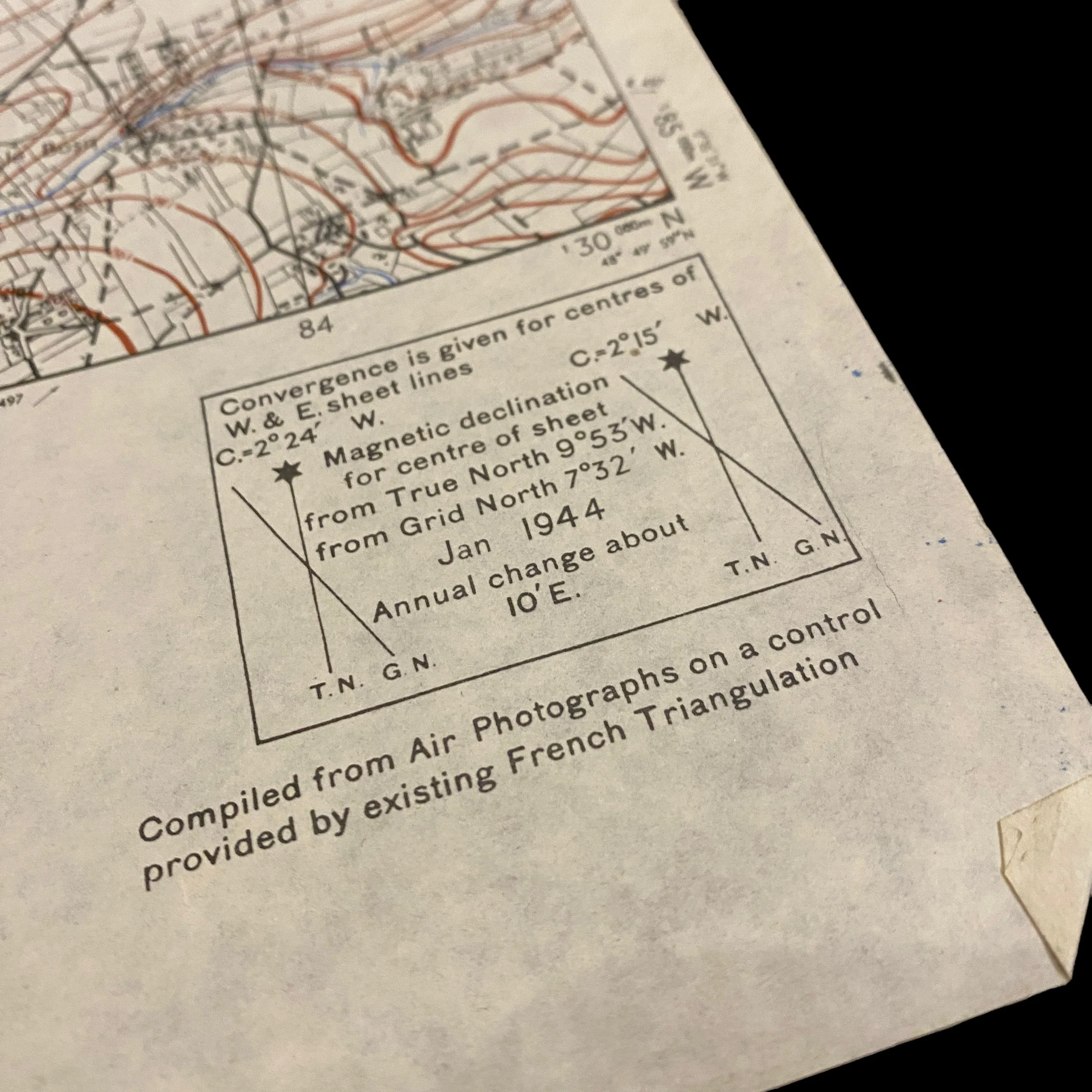

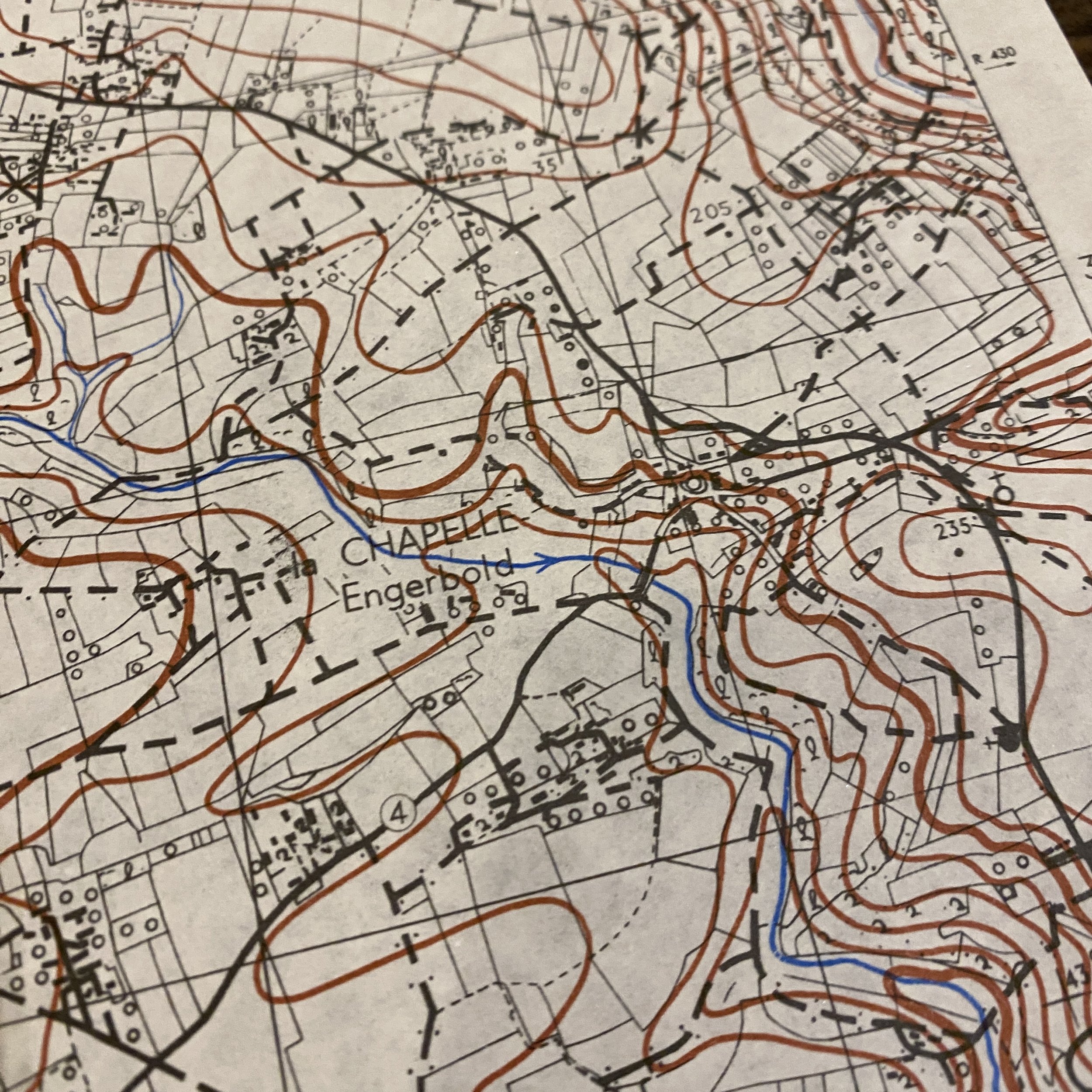

Similar to the BIGOT collection, only a small handful of this series of these Normandy combat assault maps exist. Of this series, this map was used by U.S. Infantry and Armored Divisions during the breakout of Omaha and Utah Beach (Normandy Beachheads). This map was a bring back of a WWII veteran who served in Normandy, France and used this map during combat operations in an Infantry Division.

This extremely rare and museum-grade Operation Overlord D-Day combat assault map is a part of the rare FEB. 1944 (FIRST EDITION) printing series. This map was printed just four months prior to the Allied D-Day landings on June 6th, 1944. Titled “VASSY - FRANCE” this combat assault map was used when U.S. Infantry and Armored Divisions captured Omaha Beach and pushed deeper in the Normandy region of France.

The Men And Guns Of D-Day: Omaha & The Breakout:

During the naval landings of D-Day on June 6, 1944, the situation for the U.S. 5th Corps going ashore at "Omaha" beach hung by a thread during the initial waves. The weather, which was supposed to be calm for the operation, complicated things, as swells and tides swamped several landing craft and the majority of the M4 Sherman Duplex Drive amphibious tanks, leaving infantry on the beach without armored support.

The swells also hampered the Joint Assault Signal Company (JASC) that had joined the first wave to act as fire control parties to direct in accurate naval gunfire from the vessels offshore. Water ruined their radios, and as a result, they were unable to call in desperately needed fire support. This lack of armor and direct naval gunfire support to help the infantry move up the beach contributed to the large number of casualties sustained by those landing at Omaha.

An eastward tide and smoke over the beach, which limited visibility of landmarks, caused landing craft to miss their designated sectors and drop off their passengers at the wrong area, causing confusion as units got separated. All of this went on while the Germans rained down accurate mortar and machine gun fire down onto the beach from their protected concrete bunkers from the bluffs above. Although the exact number of American servicemen killed in the landings at Omaha is still debated, it is believed to be around 1,000.

As the morning progressed and more waves came ashore at Omaha, eventually small groups of American infantryman began to work their way towards the bluffs and draws at the head of the beach. These men bravely fought their way up the bluffs and began to take on the German defenders, in an effort to stop the massacre happening below. The first group of Americans to make it to the top of the bluff were at the "Fox" sector of Omaha to the east, making their way up the "F-1" draw before coming up against the German defenders of bunker complex "WN-60," a maze of trenches and concrete emplacements containing mortars and machine guns.

Led by 2nd Lt. Jimmie W. Monteith Jr., this small group took on the German defenders in a close-quarters brawl through the complex of trenches and holes. However, a German counterattack soon cut the group off and pinned them down. In an effort to get his men out of the predicament, 2nd Lt. Monteith attempted to direct his unit out of the situation but was shot and killed in the process. For his devotion in leading his men all the way up the bluffs and to the end, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He is one of three recipients of the medal that remain interred at the Normandy American Cemetery, along with 9,386 other American servicemen who perished in the liberation of Normandy.

Despite the harsh start to the landings at Omaha on D-Day, and thanks to the influx of U.S. Rangers along with the leadership of small group leaders on the beach, U.S. troops eventually gained a foothold and began working their way up to, and beyond, the German defenses on the bluffs. Thanks in part to the efforts of 2nd Lt. Monteith and other infantrymen fighting their way up the F-1 draw, WN-60 was silenced by 9 a.m., allowing the 3rd Battalion of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division to move inland. By the end of D-Day, footholds had been established inland all along Omaha beach, but far behind what had been planned.

As the Allied landing forces began to move inland to the Normandy interior, they encountered obstacles that they had not prepared for, the Bocage region filled with overgrown hedgerows stretching for miles. These hedgerows provided excellent choke points for the Germans to set up ambushes against the advancing allies and hampered the advance further inland. Each hedgerow could become its own little closed-in battlefield, as both sides meandered through the maze of roads, fields, and overgrowth.

The situation encountered in the hedgerows removed fluidity from the battlefield and bogged down the Allied advance to a slow craw, before stalling just outside the city of Saint-Lo, France, six weeks after D-Day. The German's tenacity and effective use of the Bocage region made the process and costly and bitter fight. In an effort to break out of the Bocage, the U.S. command planned a to use a massive daylight carpet-bombing raid, with a drop zone one mile deep and five miles wide, to the west of the city. Known as Operation Cobra, this panned aerial attack would land just ahead of the 2nd Armored Division's advance, and was intended to allow it to break through the German lines into Brittany.

Commenced on July 25, 1944, the operation resulted in tragedy, as inaccurate bomb drops from the 8th Air Force carrying out the aerial half of the operation landed on American forces pushing forward, resulting in the deaths of 111 men, including Gen. Lesley McNair, the highest-ranking U.S. officer killed in the European Theater. Despite this, the massed carpet-bombing achieved its intended result as well, and softened up the German defenses standing in its wake. While U.S. infantry and armor still had to contest against surviving German units, by July 28, resistance crumbled and allowed a corridor for allied advance into France, breaking out of the Bocage and Normandy.