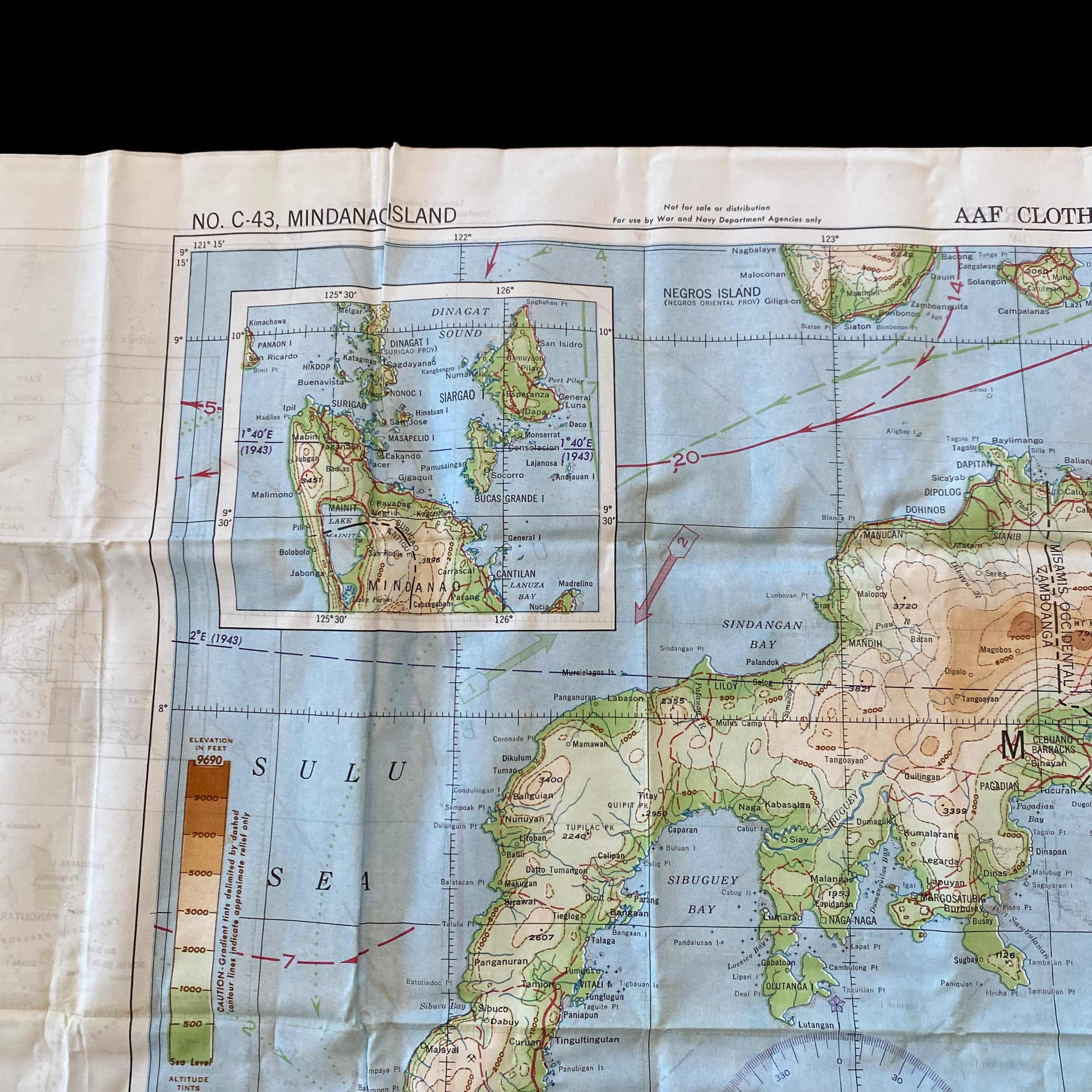

WWII RESTRICTED April 1944 Mindanao & Borneo USSAF Pilot Philippines Campaign Bailout Silk Survival Map

WWII RESTRICTED April 1944 Mindanao & Borneo USSAF Pilot Philippines Campaign Bailout Silk Survival Map

Comes with C.O.A.

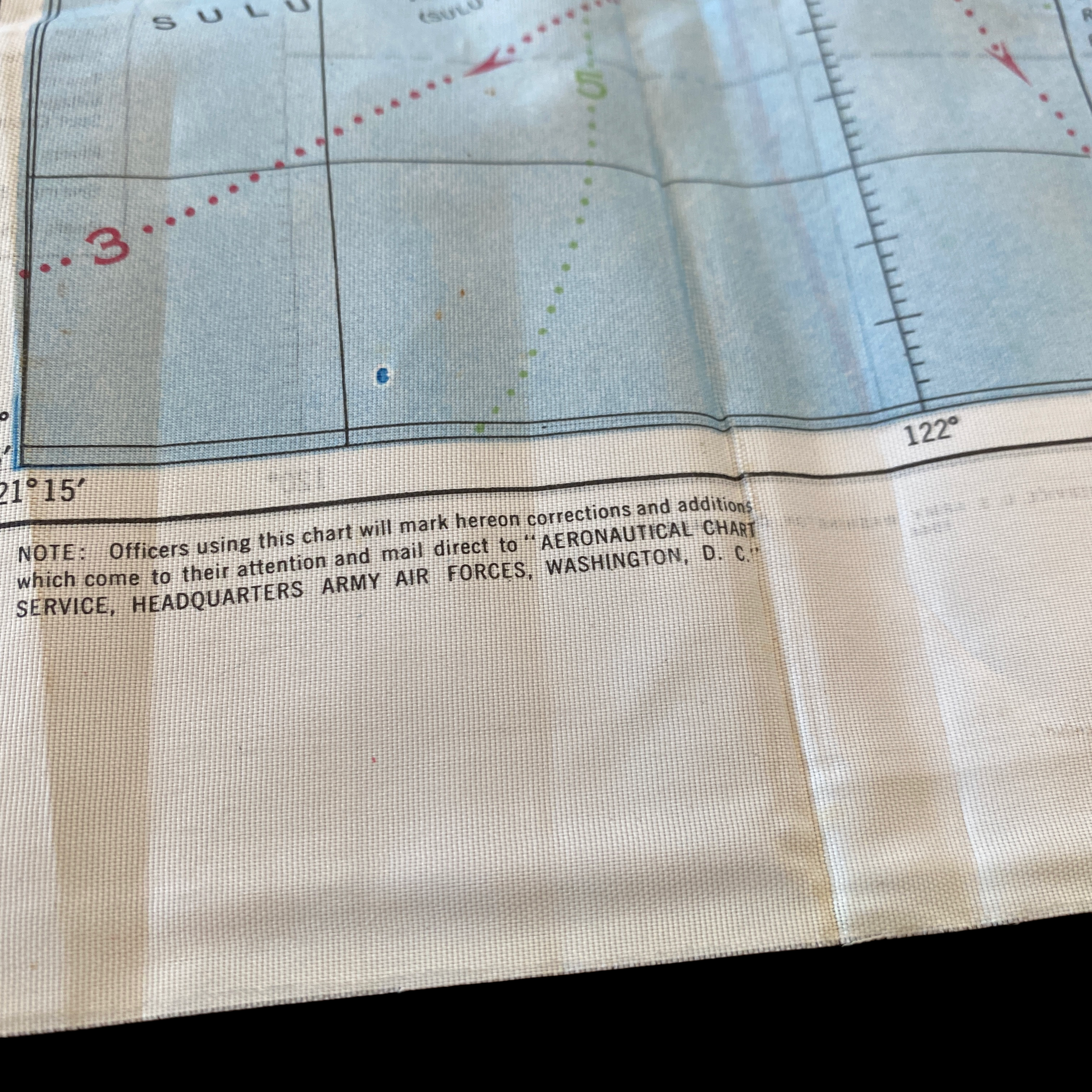

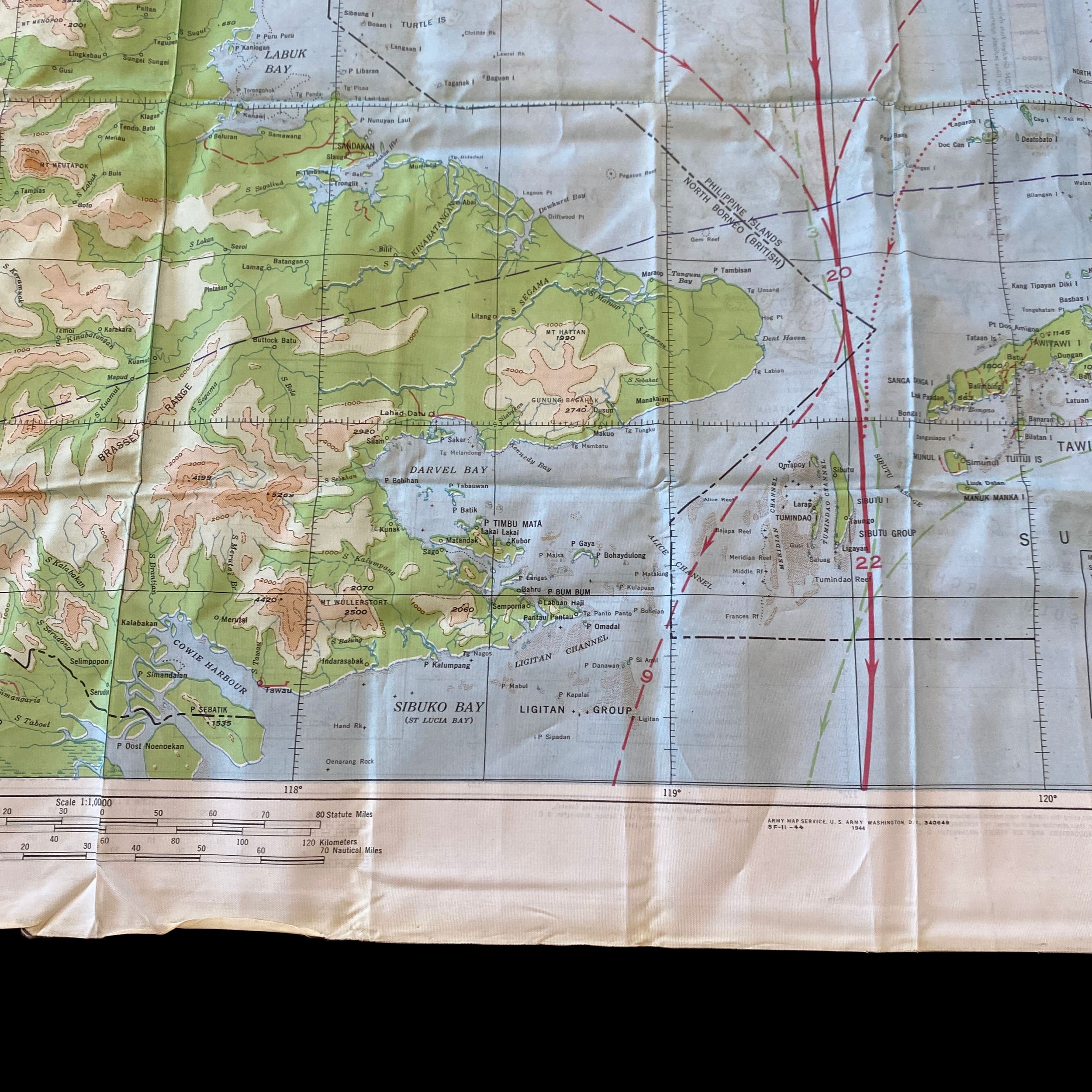

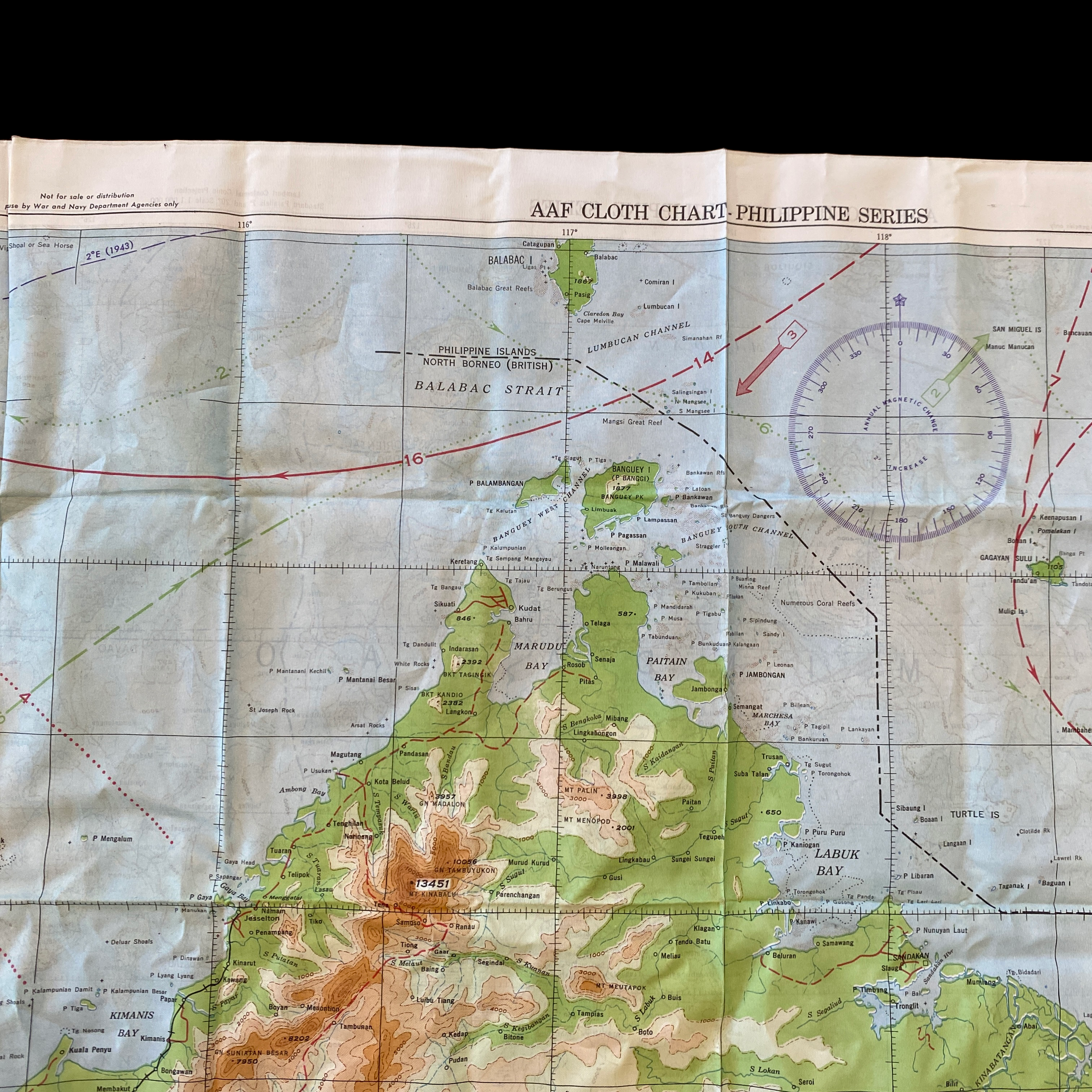

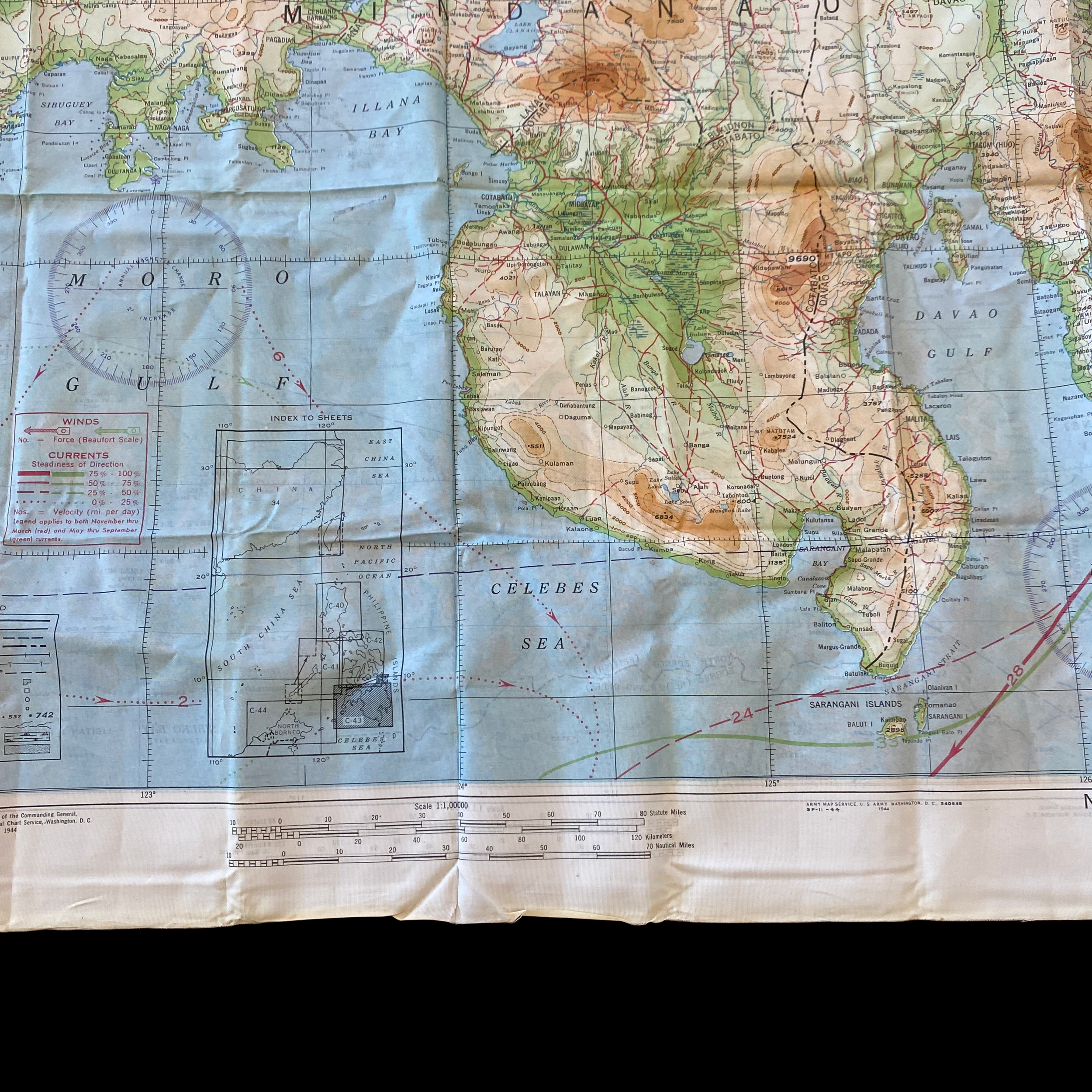

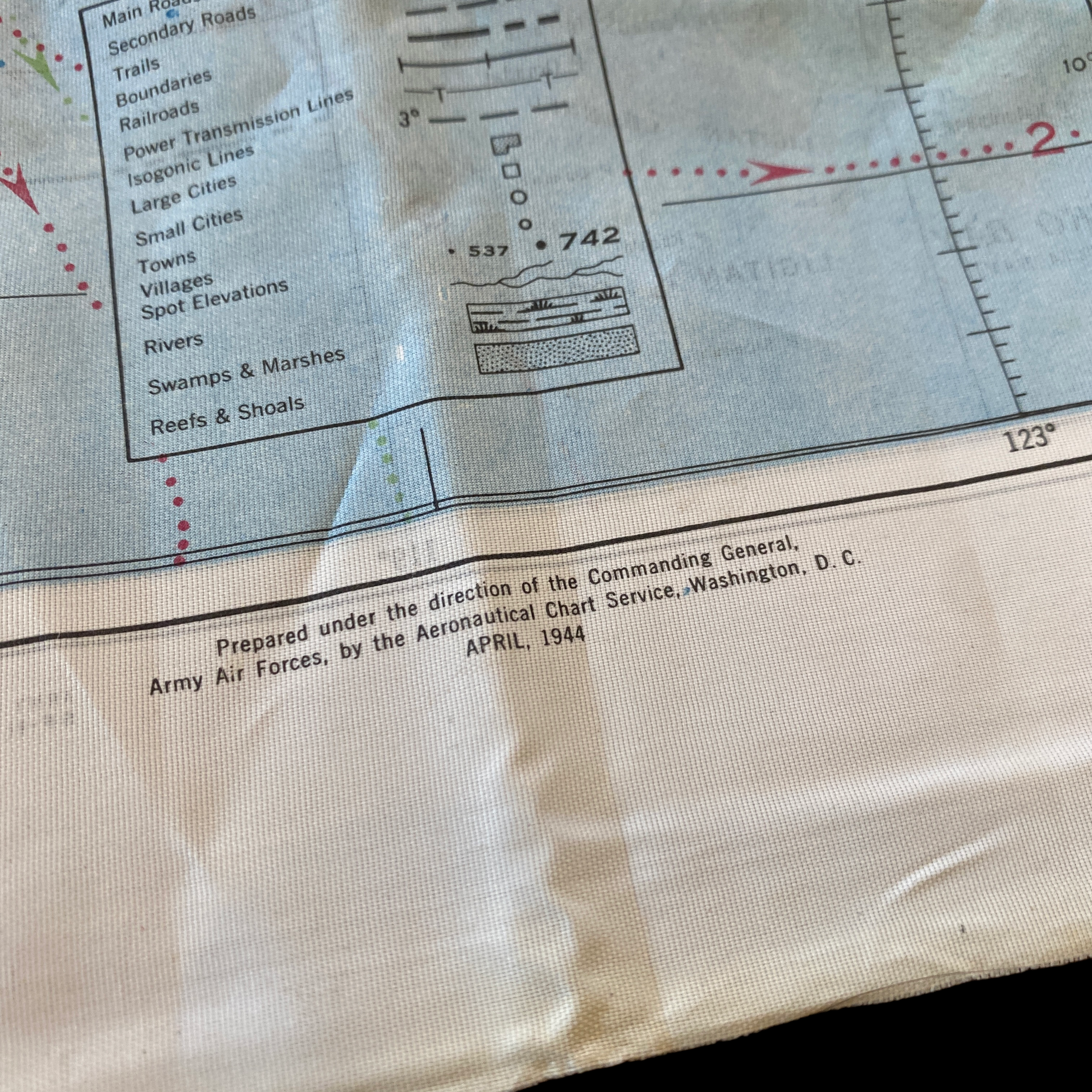

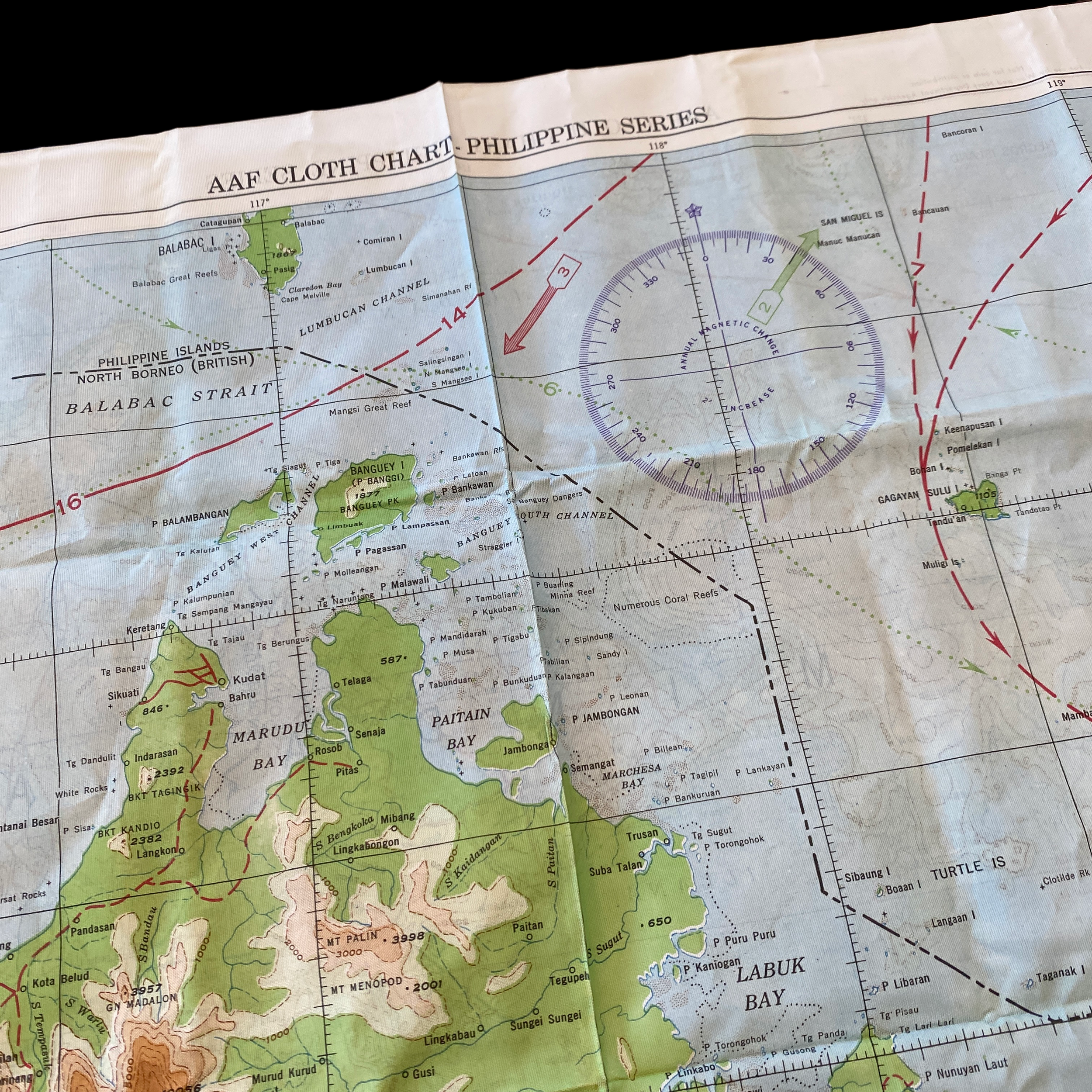

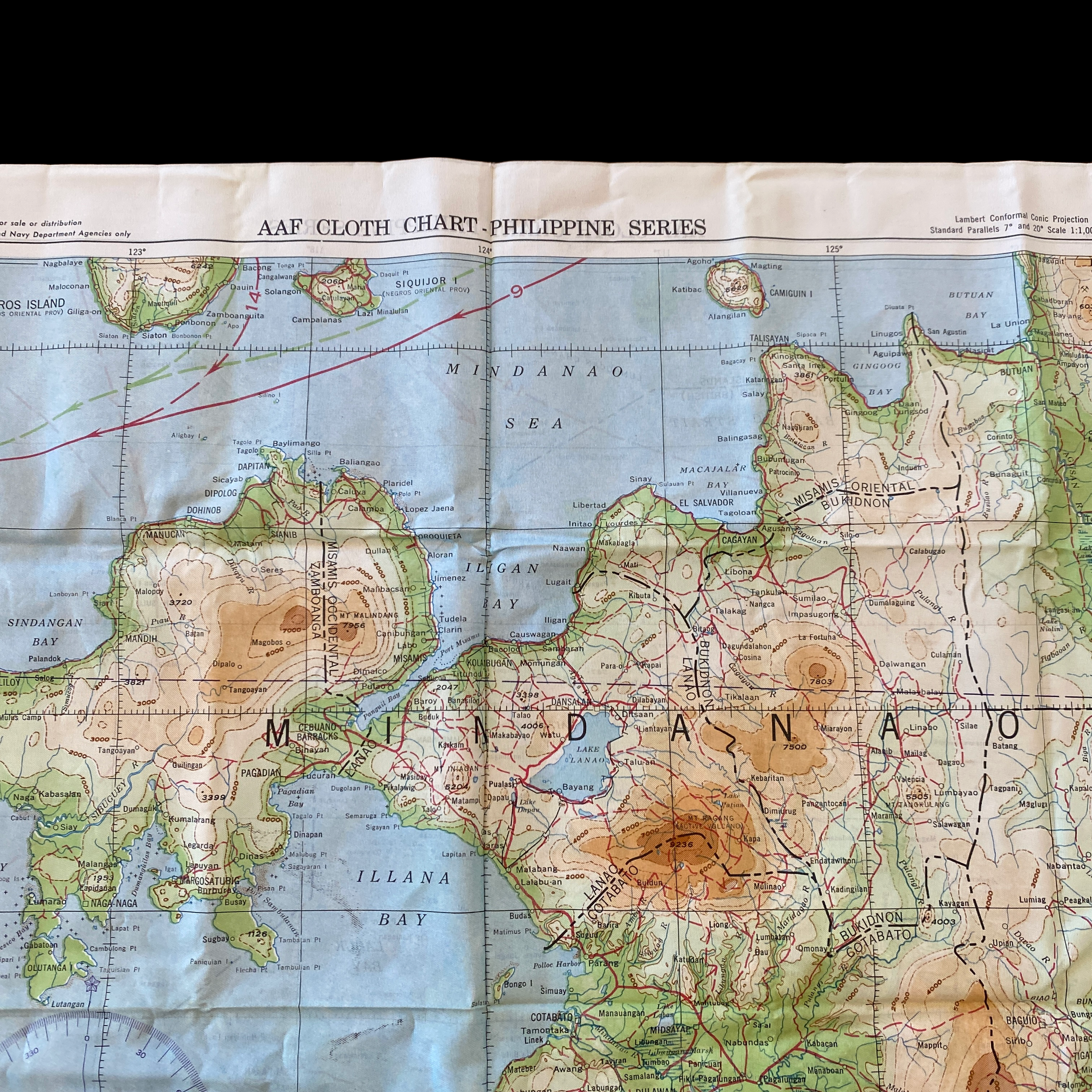

This large dobule-sided “RESTRICTED” marked Pacific Theater pilot bailout survival map is dated April 1944 and was prepared under the direction of the US ARMY AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS as USAAF pilots and USAAF bomber crew members began assaulting the Japanese during the Philippines Campaign (1944–1945). Titled “AAF CLOTH CAHRT PHILLIPPINE SERIES” this cloth chart does show signs of theater use and would have been carried by a USAAF pilot or crew participating in the Philippines Campaign.

These cloth charts were worn as neck scarves or stuffed in the pant/jacket pockets by pilots during WWII as part of their survival gear. During WWII these silk bailout maps were produced in varying quantities by the Allied forces on thin silk (waterproof) material. The idea was that if an Allied pilot’s plane was shot down behind enemy lines they should have a map to help him find his way to safety if he escaped or evade capture.

This World War II USAAF bailout map shows some of the most famous islands of the Philippines Campaign including North Borneo, and Mindanao, and many other smaller island chains surrounding that same region.

The Philippines campaign, Battle of the Philippines or the Liberation of the Philippines, codenamed Operation Musketeer I, II, and III, was the American, Mexican, Australian, and Filipino campaign to defeat and expel the Imperial Japanese forces occupying the Philippines during World War II.

Planning for the Philippines Campaign:

By mid-1944, American forces were only 300 nautical miles (560 km) southeast of Mindanao, the largest island in the southern Philippines – and able to bomb Japanese positions there using long-range bombers. American forces under Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz had advanced across the Central Pacific Ocean, capturing the Gilbert Islands, some of the Marshall Islands, and most of the Marianas Islands, bypassing many Japanese Army garrisons and leaving them behind, with no source of supplies and militarily impotent.

Aircraft carrier-based warplanes were already conducting air strikes and fighter sweeps against the Japanese in the Philippines, especially their military airfields. U.S. Army and Australian Army troops under the American General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Theater of Operations, had either overrun, or else isolated and bypassed, all of the Japanese Army on New Guinea and the Admiralty Islands. Before the invasion of the Philippines, MacArthur's northernmost conquest had been at Morotai in the Dutch East Indies on September 15–16, 1944. This was MacArthur's one base that was within bomber range of the southern Philippines.

U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Army as well as Australian and New Zealand forces under the command of Admiral Nimitz and Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr. had isolated the large Japanese South Pacific base at Rabaul, New Britain, by capturing a ring of islands around Rabaul, and then building air bases on them from which to bomb and blockade the Japanese forces at Rabaul into military impotence.

With victories in the Marianas campaign (on Saipan, on Guam, and on Tinian, during June and July 1944), American forces were getting close to Japan itself. From the Marianas, the very long-range B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers of the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) could bomb the Japanese home islands from well-supplied air bases – ones with direct access to supplies via cargo ships and tankers. (The earlier B-29 bombing campaign against Japan had been from the end of a very long and tortuous supply line via British India and British Burma – one that proved to be woefully inadequate. All B-29s were transferred to the Marianas during the fall of 1944.)

Although Japan was obviously losing the war, the Japanese Government, and the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, showed no sign of capitulation, collapse, or surrender.

There had been a close relationship between the people of the Philippines and the United States since 1898, with the Philippines becoming the Commonwealth of the Philippines in 1935, and promised their independence in mid-1946. Furthermore, an extensive series of air attacks by the American Fast Carrier Task Force under Admiral William F. Halsey against Japanese airfields and other bases on the Philippines had drawn little Japanese opposition, such as interceptions by the Japanese Army fighter planes. Upon Admiral Halsey's recommendation, the Combined Chiefs of Staff, meeting in Canada, approved a decision to not only move up the date for the first landing in the Philippines but also to move it north from the southernmost island of Mindanao to the central island of Leyte, Philippines. The new date set for the landing on Leyte, October 20, 1944, was two months before the previous target date to land on Mindanao.

The Filipino people were ready and waiting for the invasion. After General MacArthur had been evacuated from the Philippines in March 1942, all of its islands fell to the Japanese. The Japanese occupation was harsh, accompanied by atrocities and with large numbers of Filipinos pressed into slave labor. From mid-1942 through mid-1944, MacArthur and Nimitz supplied and encouraged the Filipino guerrilla resistance by U.S. Navy submarines and a few parachute drops, so that the guerrillas could harass the Japanese Army and take control of the rural jungle and mountainous areas – amounting to about half of the archipelago. While remaining loyal to the United States, many Filipinos hoped and believed that liberation from the Japanese would bring them freedom and their already-promised independence.

The Australian government offered General MacArthur the use of the First Corps of the Australian Army for the Liberation of the Philippines. MacArthur suggested that two Australian infantry divisions be employed, each of them attached to a different U.S. Army Corps, but this idea was not acceptable to the Australian Cabinet, which wanted to have significant operational control within a certain area of the Philippines, rather than simply being part of a U.S. Army Corps.[20] No agreement was ever reached between the Australian Cabinet and MacArthur – who might have wanted it that way. However, units from the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal Australian Navy, such as the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia, were involved.

During the American re-conquest of the Philippines, the guerrillas began to strike openly against Japanese forces, carried out reconnaissance activities ahead of the advancing regular troops, and took their places in battle beside the advancing American divisions.