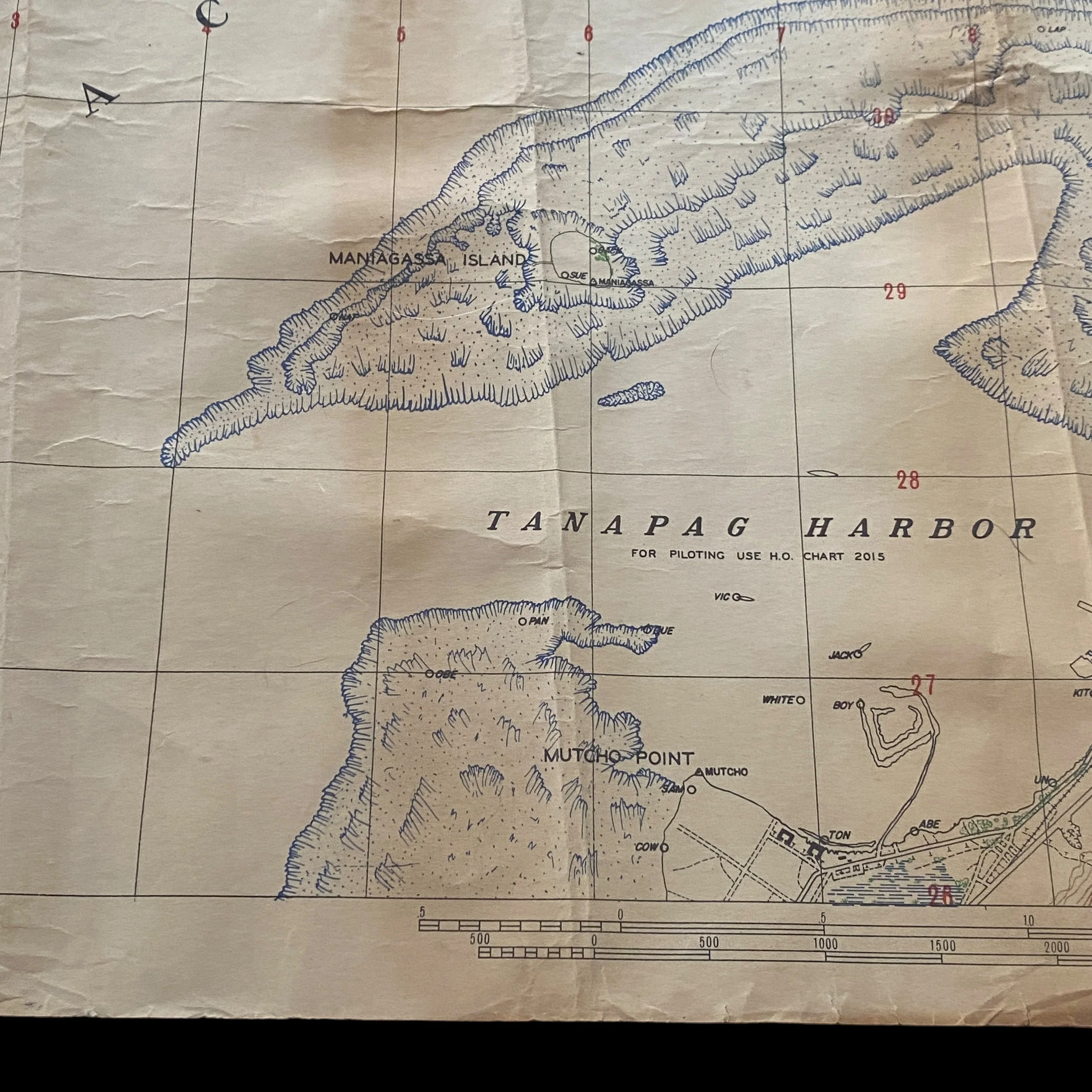

RARE! WWII 1944 Saipan 2nd Marine Division "RESTRICTED" Operation Forger Artillery Firing Sector Map (Tanapag Harbor)

RARE! WWII 1944 Saipan 2nd Marine Division "RESTRICTED" Operation Forger Artillery Firing Sector Map (Tanapag Harbor)

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

Titled “2ND MARINE DIVISION - FIRE CONTROL MAP” this original, ultra rare, and museum-grade 1944 dated Saipan “RESTRICTED” Saipan map vividly illustrates the intensive planning and operational accuracy that was behind Operation Forger and the U.S. assault on the Mariana Islands from June 15th through July 9th, 1944. Prepared by the 2nd Engineer Battalion, 2nd Marine Division this heavily used map is a very limited print count and was specially prepared for the 2nd Marine Division.

In March 1944, the Joint Chiefs of Staff concluded that the seizure of the Mariana Islands would be the next logical step in bringing about the downfall of the Japanese Empire. The Marianas were a vital link in Japan’s line of defenses; they were the key to the Central Pacific because the islands dominated Japan’s lines of communication for its “Inner South Seas Empire.” The capture of the Marianas would not only cut the enemy’s defenses, but would also provide air and sea bases from which the United States could effectively strike at the Philippines, Formosa, China, and the Japanese home islands.

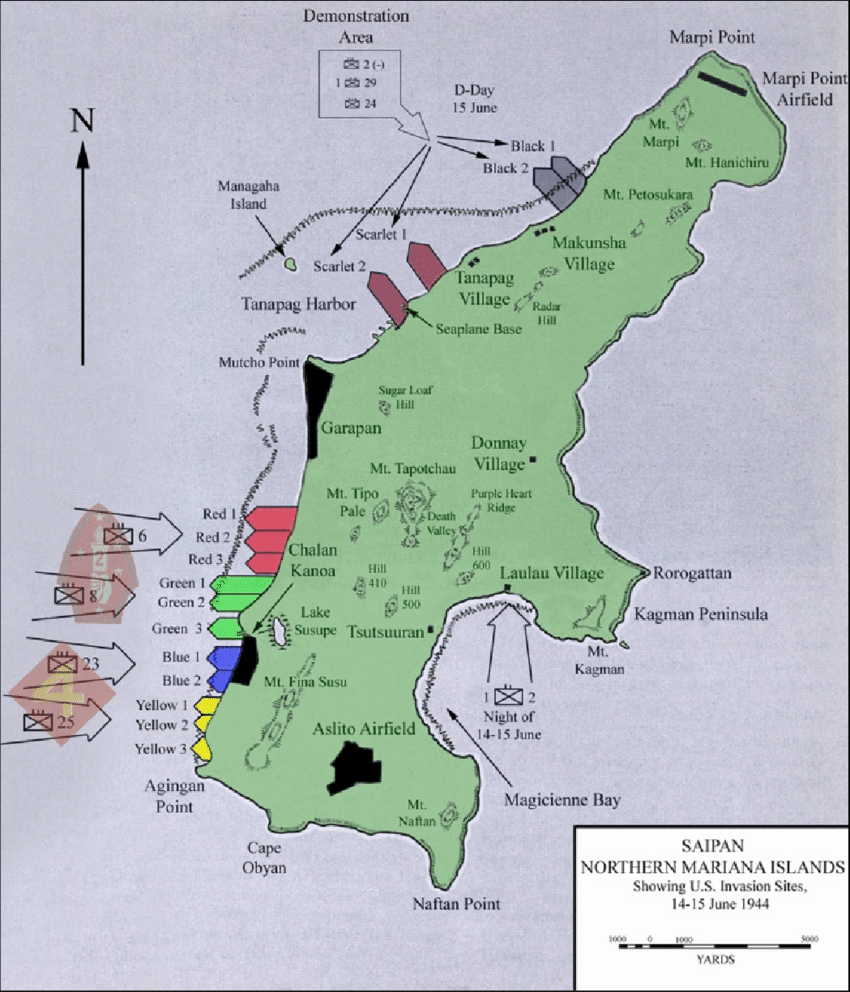

Saipan was selected as the first target in the invasion of the Marianas. D-Day was set for 15 June 1944. LtGen Holland M. Smith was given over-all command of the landing force which consisted of: the 2d Marine Division under MajGen Thomas E. Watson; the 4th Marine Division under MajGen Harry Schmidt; and, in reserve, the 27th Infantry Division (Army) under MajGen Ralph C. Smith and later under MajGen Sanderford Jarman.

Waiting for the Americans were nearly 30,000 enemy troops, though intelligence reports had placed the figure at 19,000. The invasion of Saipan was unique in the Central Pacific campaign; it was the first time in that area that an amphibious assault was made on a sizable, mountainous land mass, as contrasted with previous attacks on tiny, flat coral atolls.

Beginning on 11 June, Saipan was subjected to intensive air and naval bombardment. This preparation, however, proved to be inadequate in neutralizing the enemy in the landing areas. Shortly after 8:00am on 15 June, the 2d and 4th Marine Divisions, many of whose men were veterans of hard-won victories in the Gilbert and the Marshall Islands, embarked on landing craft and headed for the southwest coast of the island. As the amphibian tractors (LVTs) neared the beaches, the enemy unexpectedly began firing a heavy fusillade from automatic and anti-boat weapons, along with devastating shelling from artillery and mortars. A number of the LVTs, as a result, were either sunk or disabled. Nonetheless, 8,000 men were landed in 20 minutes.

Casualties mounted because of the congestion and confusion that occurred on the beaches. The LVTs, in many cases, disembarked the troops short of the original landing zones. The entire 2d Marine Division was landed by error nearly 900 yards north of the assigned beaches and hence lost contact with the 4th Marine Division. Although both divisions made it ashore, the price was very high with over 2,000 casualties in the first day’s fighting.

The Japanese continued to fiercely resist the invaders after the beachhead had been secured. Counterthrusts were launched on the 16th and 17th, including a large scale tank attack. These were repulsed but with severe losses to the Marines. The extremely heavy casualties and the intensity of the enemy’s resistance induced Gen Holland Smith to revise his plan for the conquest of the island. Since all the Marine reserve regiments had been committed, Gen Smith decided to land the Army’s 27th Infantry Division. The first Army elements came ashore on the night of the 16th, but the movement was not completed until the 20th.

In the meantime, the Marines struck out from the beachhead, moving eastward. By the 18th, the island was bisected when Marine units reached the east coast. The next day the gap between the two divisions was closed and both were now in a position to drive northward against the second line of enemy defenses. Units of the 27th Infantry Division were given the tasks of mopping-up areas that were by-passed by the Marines and destroying the remnants of the enemy that were trapped on Nafutan Point, the southeastern peninsula of the island.

While the Marines were preparing to strike northward on Saipan, the U.S. Navy secured a great victory far out to sea. A powerful Japanese flotilla, including a large armada of aircraft carriers, was dispatched to the Marianas to destroy the attack force at Saipan. On 19 June, Task Force 58 met the Japanese off Guam and forced their withdrawal, thus ending the threat to the troops on the island. In the engagement, which is known as the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Japanese lost three aircraft carriers and hundreds of aircraft. This victory guaranteed the United States uncontested control of the seas adjacent to Saipan while frustrating any future counter-landings by the enemy.

After the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Marines began moving north over craggy, precipitous terrain. Progress was slow and as a result, the 27th Infantry Division was ordered to the front lines to help the Marines gain momentum in the drive. On 23 June, the three divisions launched a coordinated attack into a densely wooded and mountainous area which impeded progress. Against determined resistance from the enemy, the 2d Marine Division on the left flank and the 4th Marine Division on the right flank seized their objectives; however, the Army’s attack in the center faltered. In this area, known as Death Valley, the Japanese had their strongest defenses. The soldiers could make no headway which left the flanks of the two Marine divisions over-exposed. The Marines, then, had to retard their advance until the center could be brought forward.

Although the 27th Infantry Division’s drive was stymied, the following day saw both Marine divisions once again advancing and fanning out as rapidly as possible under the circumstances. At the end of the day on the 24th, major advances were made with the 2d Marines reaching the outskirts of Garapan, the island’s principal town. After making no forward progress, the 27th Infantry Division decided to abandon the frontal assault of Death Valley and instead moved to occupy the hills above the valley. By 30 June, the 27th Infantry Division had swept through the hills and then down the valley where it finally destroyed the enemy.

While the main fighting was occurring in the central part of the island, the Japanese who were hemmed in at Nafutah Point broke through the encirclement of the Army’s 2d Battalion, 105th Infantry and struck at Aslito Airfield, the former Japanese airdome. There they burned American aircraft and attacked units of the 14th and 25th Marines. A line of defense was soon established in which the Seabees and Marine pilots joined the two regiments in annihilating the attacking Japanese force of about 500 men.

On 1 July, a drive on Garapan was launched. After three days, the town fell to the 2d Marine Division, which then went into reserve while the other two divisions continued pushing north. Yet all was not over, for the Japanese launched one more attack, their biggest and last of the campaign. Early in the morning of 7 July, thousands of enemy troops fell upon the Army’s 105th Infantry Regiment in a final, desperate banzai charge. After attacking the regiment and bypassing the positions held by two of its battalions, the Japanese hit the 3d Battalion, 10th Marines, an artillery unit. The Marines fired their howitzers at point blank range and then seized pistols, rifles, and BARs and fought as infantry, although the momentum of the attack forced the battalion back to new positions. As the Japanese surged forward, they struck at the 4th Battalion, 10th Marines, which held its position. Meanwhile two secondary attacks were launched against units of the 27th Infantry Division, but these were repulsed.

Hardest hit in the Japanese counterattack was the 105th Infantry. The 1st and 2d Battalions, suffering heavy casualties and finding themselves cut off from friendly lines, moved to form a perimeter defense at the village of Tanapag on the coast. There they fought off a succession of thrusts, which continued for 15 hours. The 106th Infantry attempted to reach the stranded soldiers but was turned back. The men of the 105th were finally evacuated by amphibian tractors.

Although the enemy had proceeded in breaking through American lines and in causing great havoc, the Japanese were not able to hold the ground they had retaken. The banzai attack had decimated their ranks and those who survived the battle withdrew. The salient feature of this engagement was the fact that the enemy no longer had the capacity or strength to launch any further offensive operations.

On the 8th, the 2d Marine Division replaced the 27th Infantry Division in the front lines and then advanced rapidly with the 4th Marine Division against the shattered Japanese. A day later, the Marines reached Marpi Point, the northernmost point of the island, where hundreds of enemy soldiers and civilians leapt to their death from the rocky ridges rather than surrender. The island was declared secure that day, although mopping-up operations continued for months, forcing out stubborn groups of enemy soldiers that had taken refuge in the caves that abounded on the island.

The cost of this campaign was great: over 16,500 casualties, including almost 3,500 killed. The Marine units suffered close to 13,000 casualties. Although the price for victory was high, the seizure of Saipan was a highly significant step forward in the advance on the Japanese home islands. The island became the first B-29 base in the Pacific. The war had reached a new turning point. Some highly-placed Japanese felt that their defeat on Saipan signified the beginning of the end of the Empire.