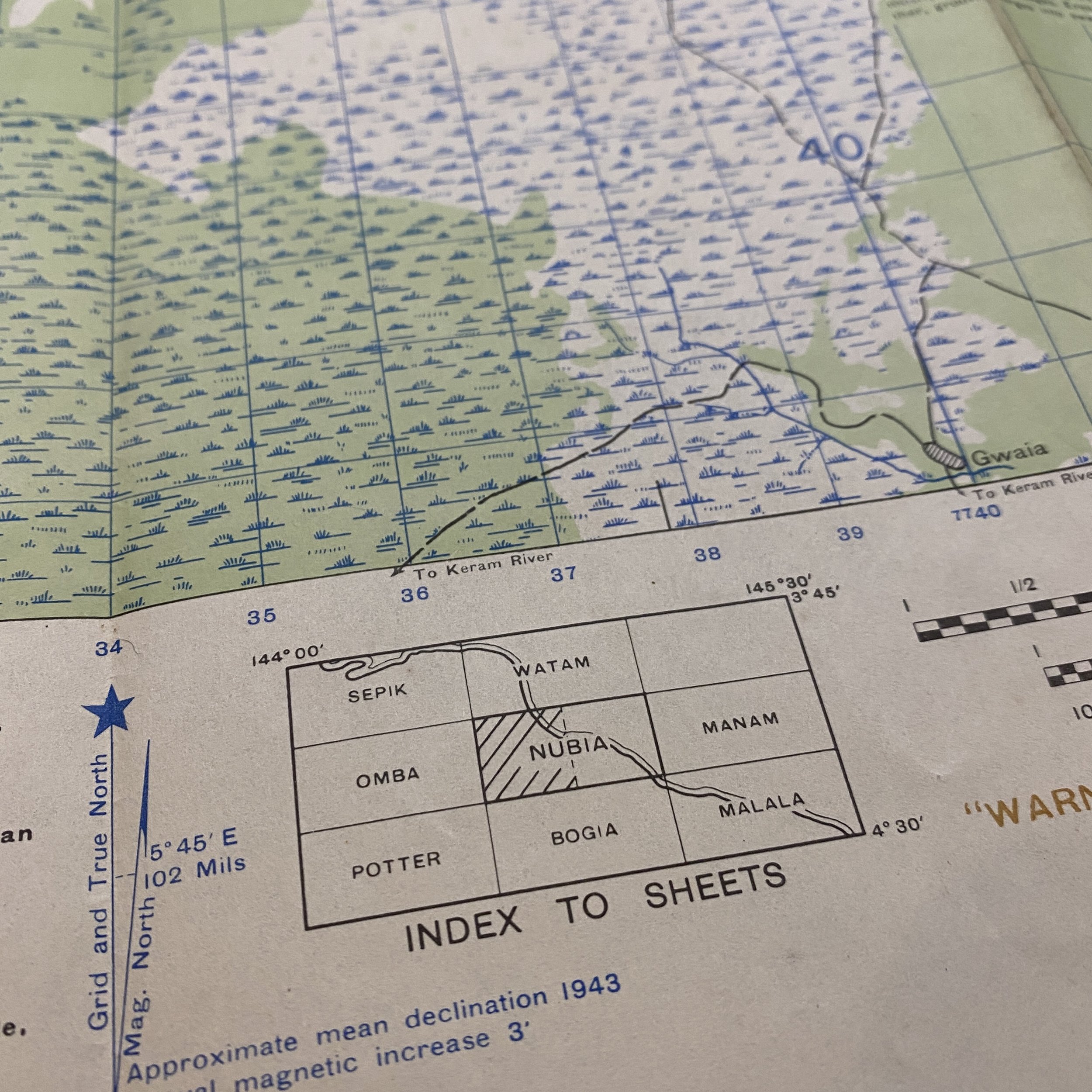

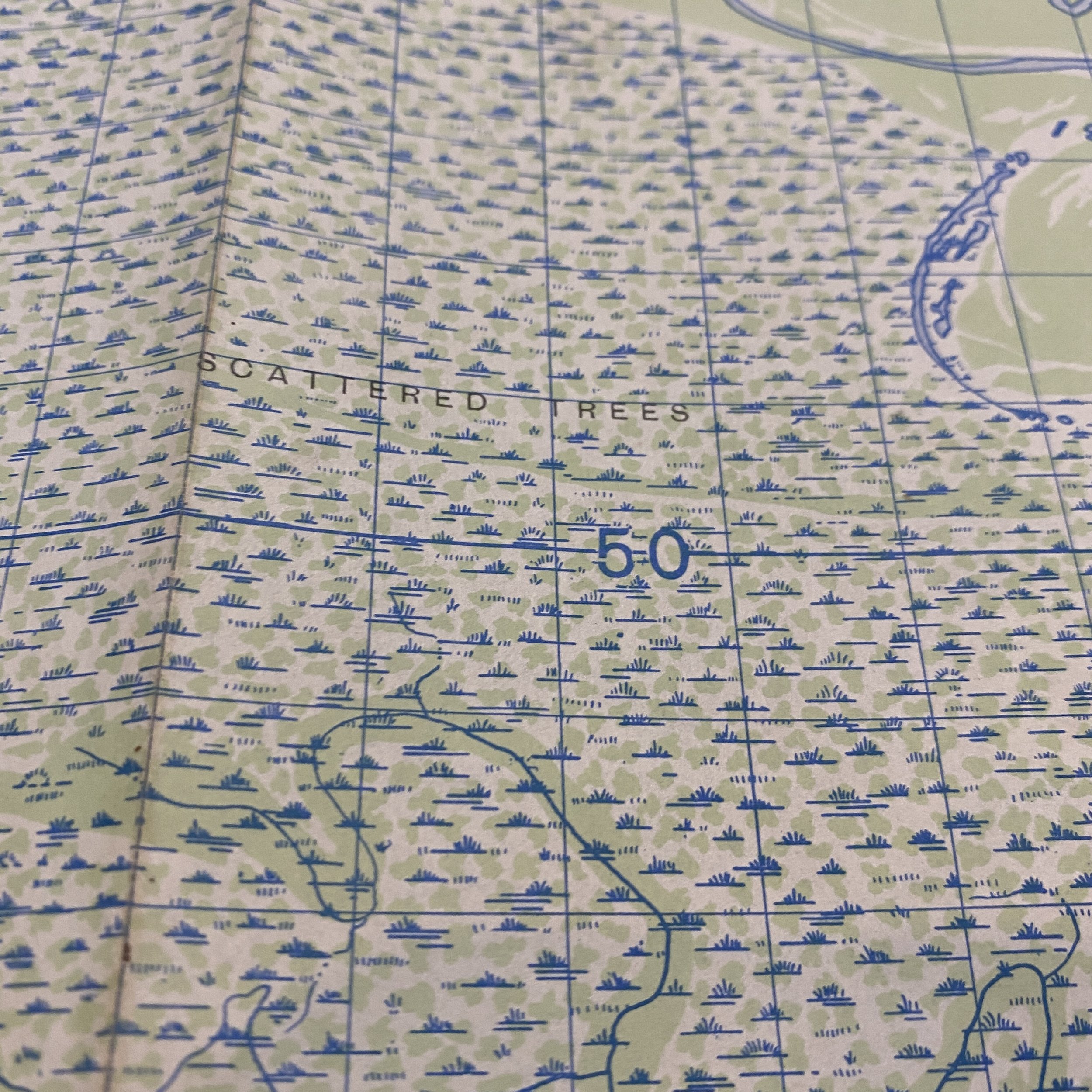

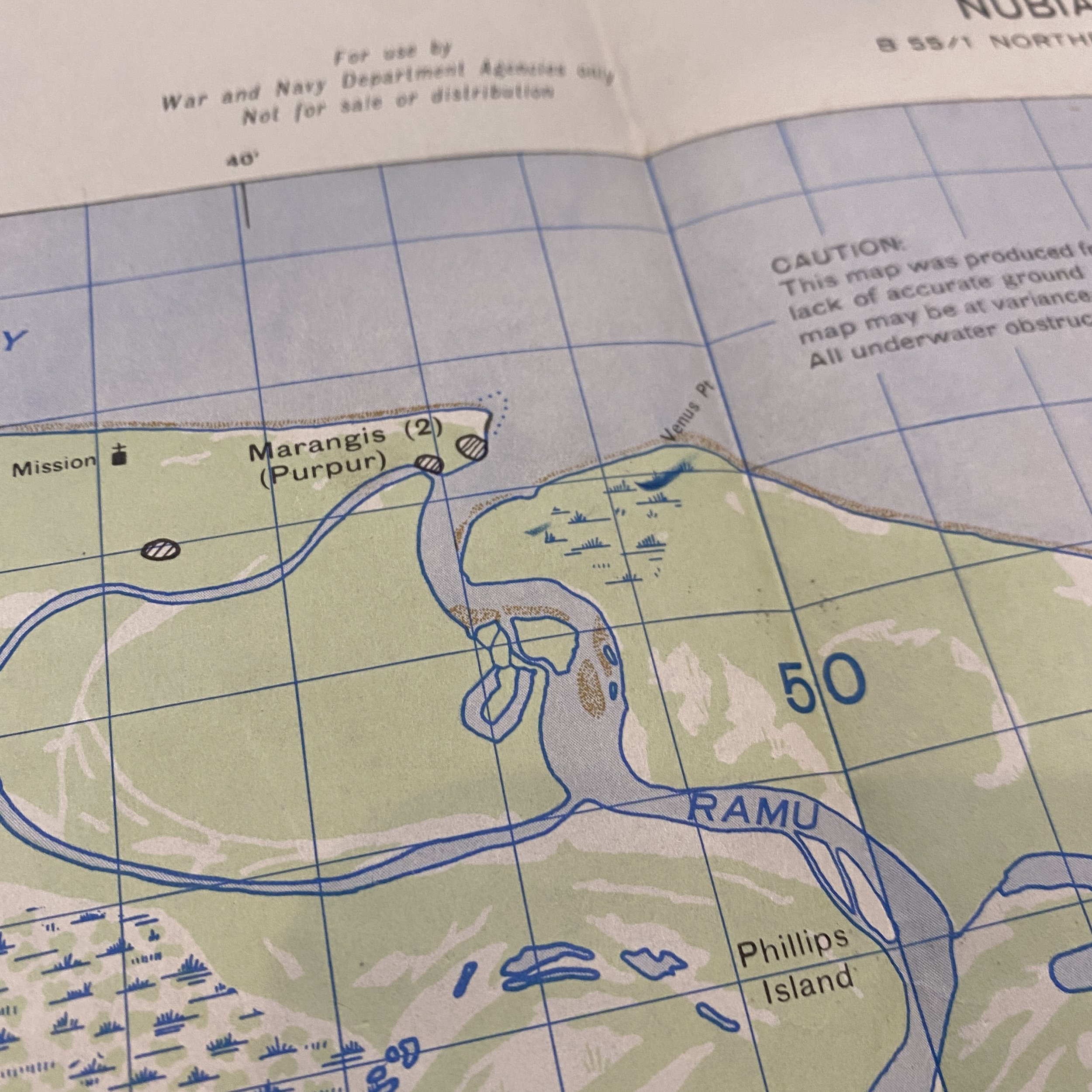

RARE! New Guinea NUBIA 1943 Invasion Map Operation Michaelmas - Pacific Theater Operations

RARE! New Guinea NUBIA 1943 Invasion Map Operation Michaelmas - Pacific Theater Operations

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

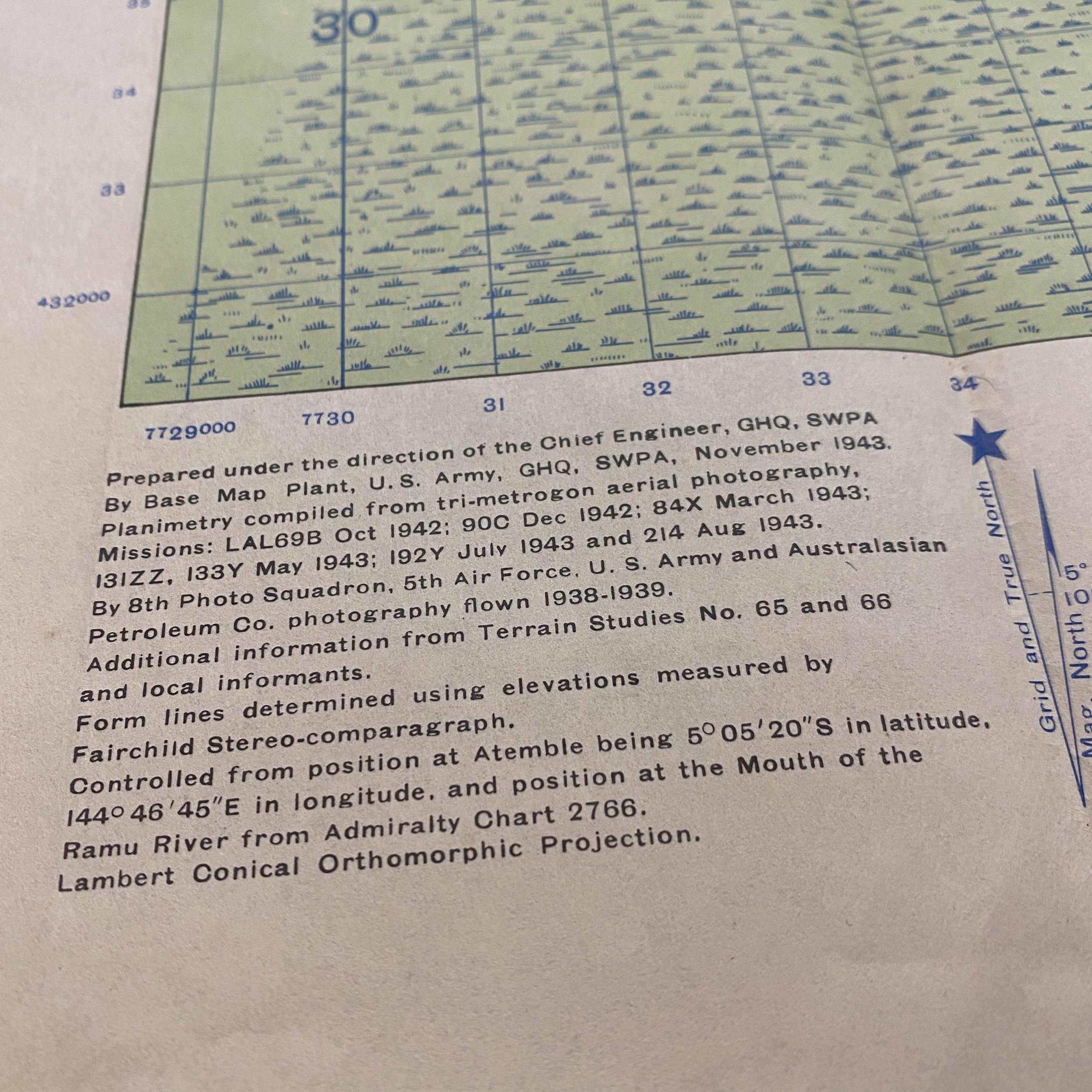

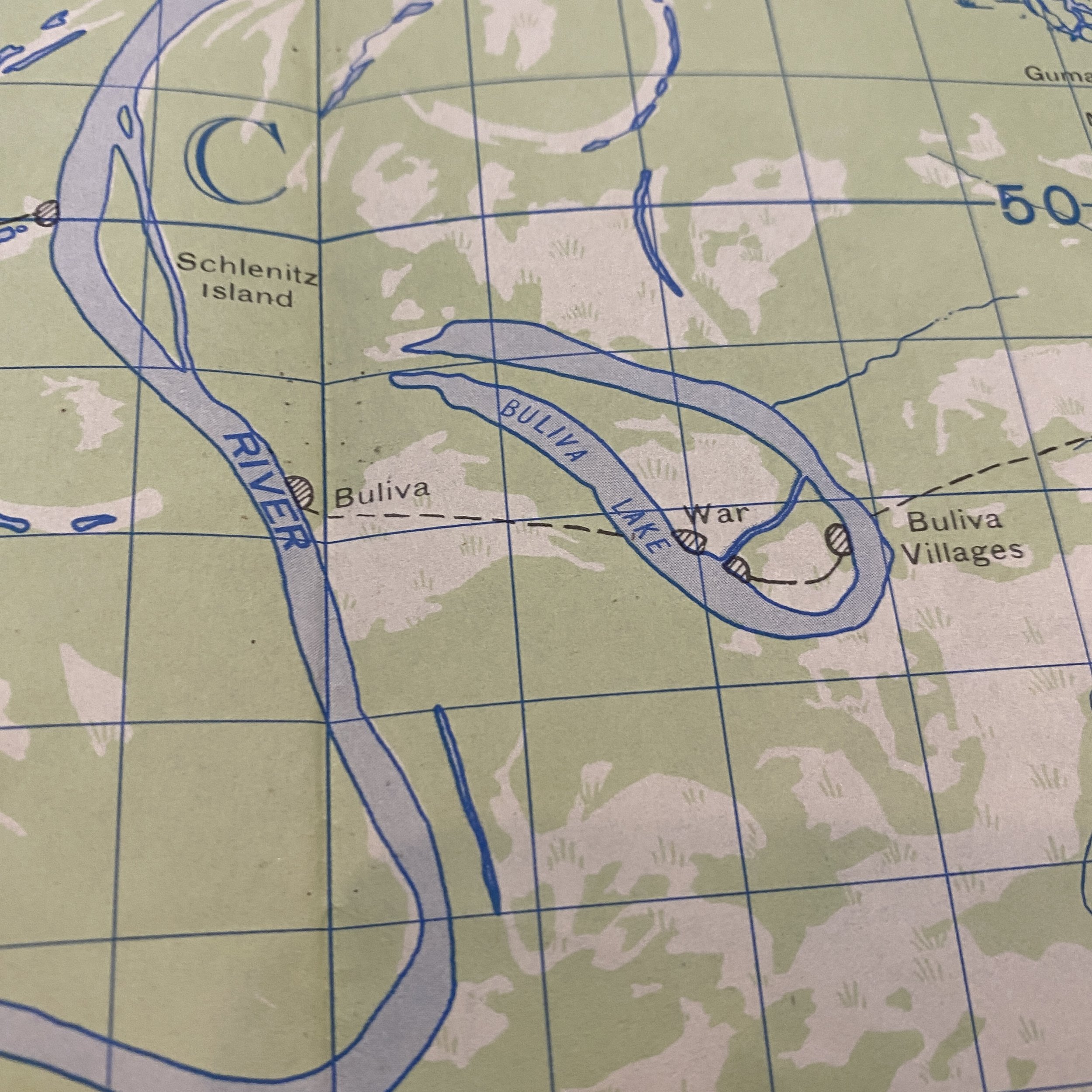

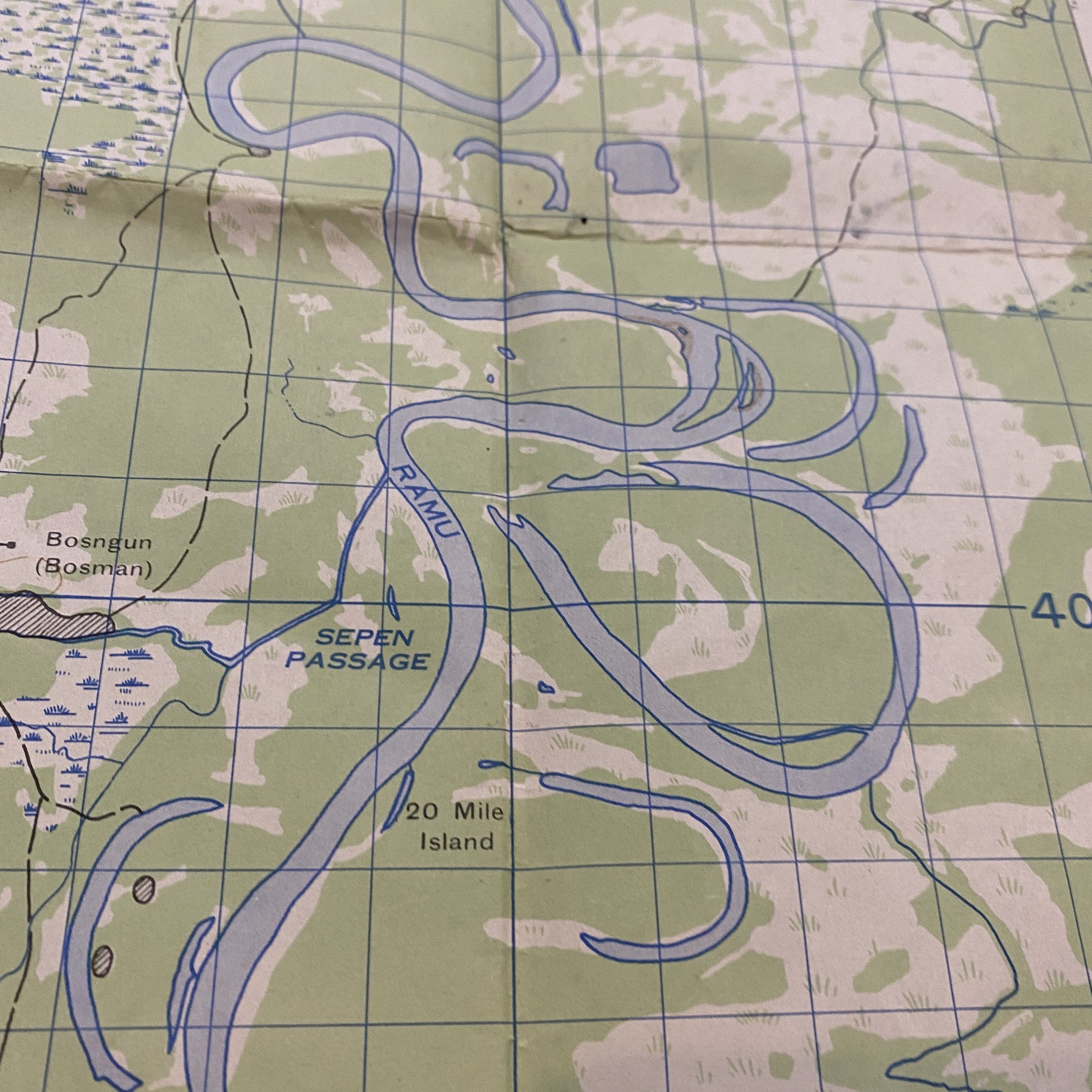

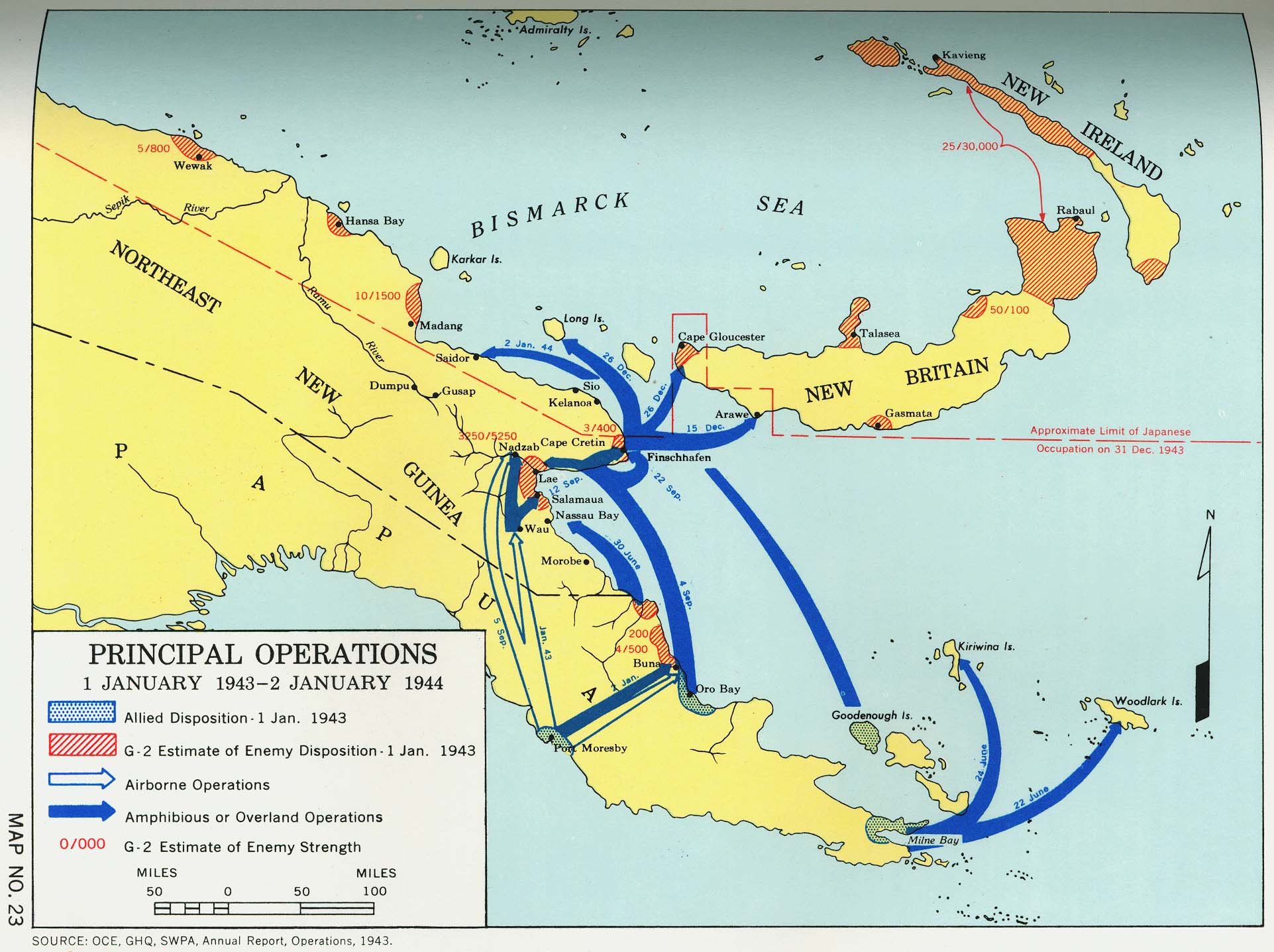

This incredibly rare and museum-grade WWII combat map was used following the famous landing at Saidor, codenamed Operation Michaelmas, which was the Allied amphibious landing at Saidor, Papua New Guinea on January 2nd 1944 as part of Operation Dexterity during World War II. In Allied hands, Saidor was a stepping stone towards Madang, the ultimate objective of General Douglas MacArthur's Huon Peninsula campaign. The capture of the airstrip at Saidor also allowed construction of an airbase to assist Allied air forces to conduct operations against Japanese bases at Wewak and Hollandia. But MacArthur's immediate objective was to cut off the 6,000 Imperial Japanese troops retreating from Sio in the face of the Australian advance from Finschhafen.

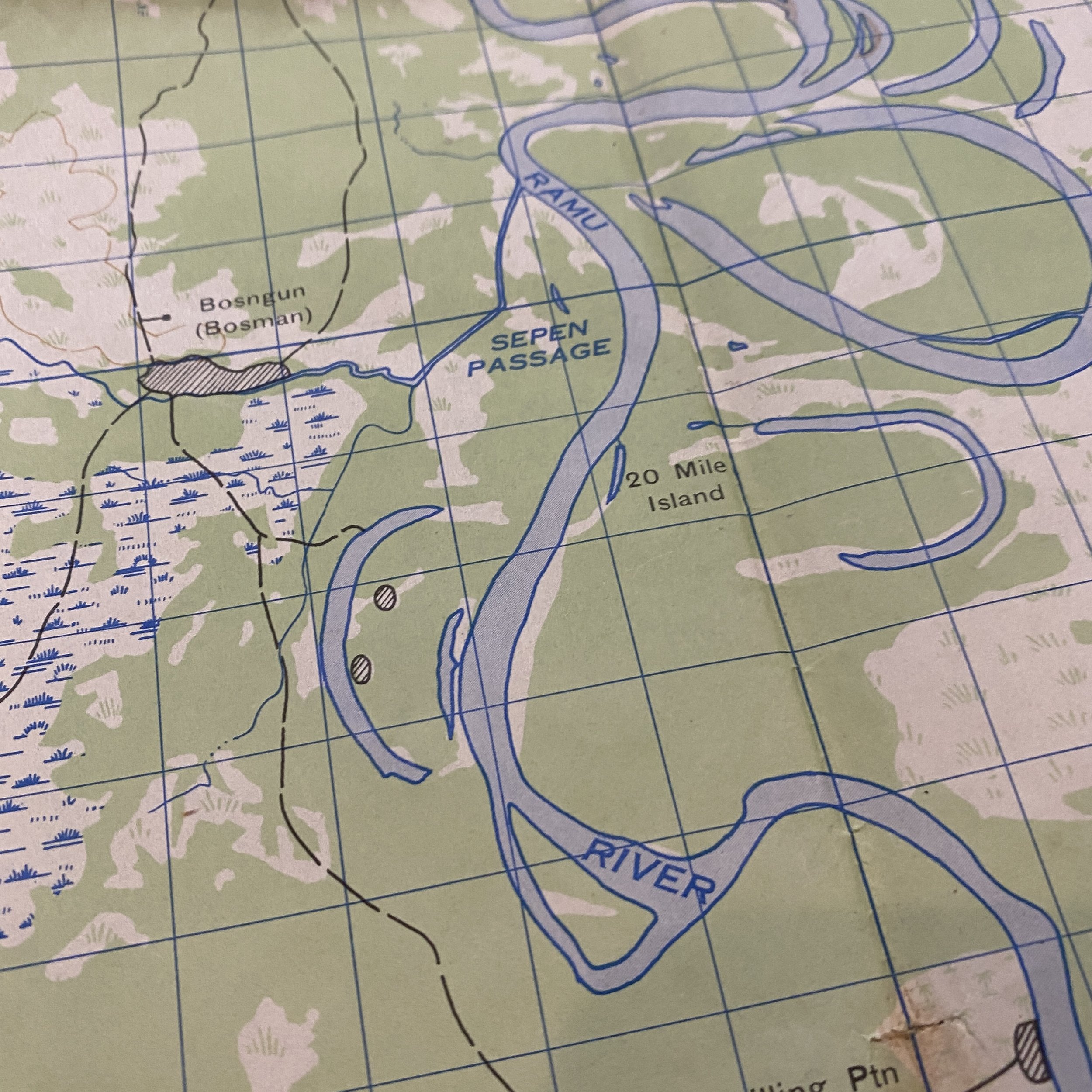

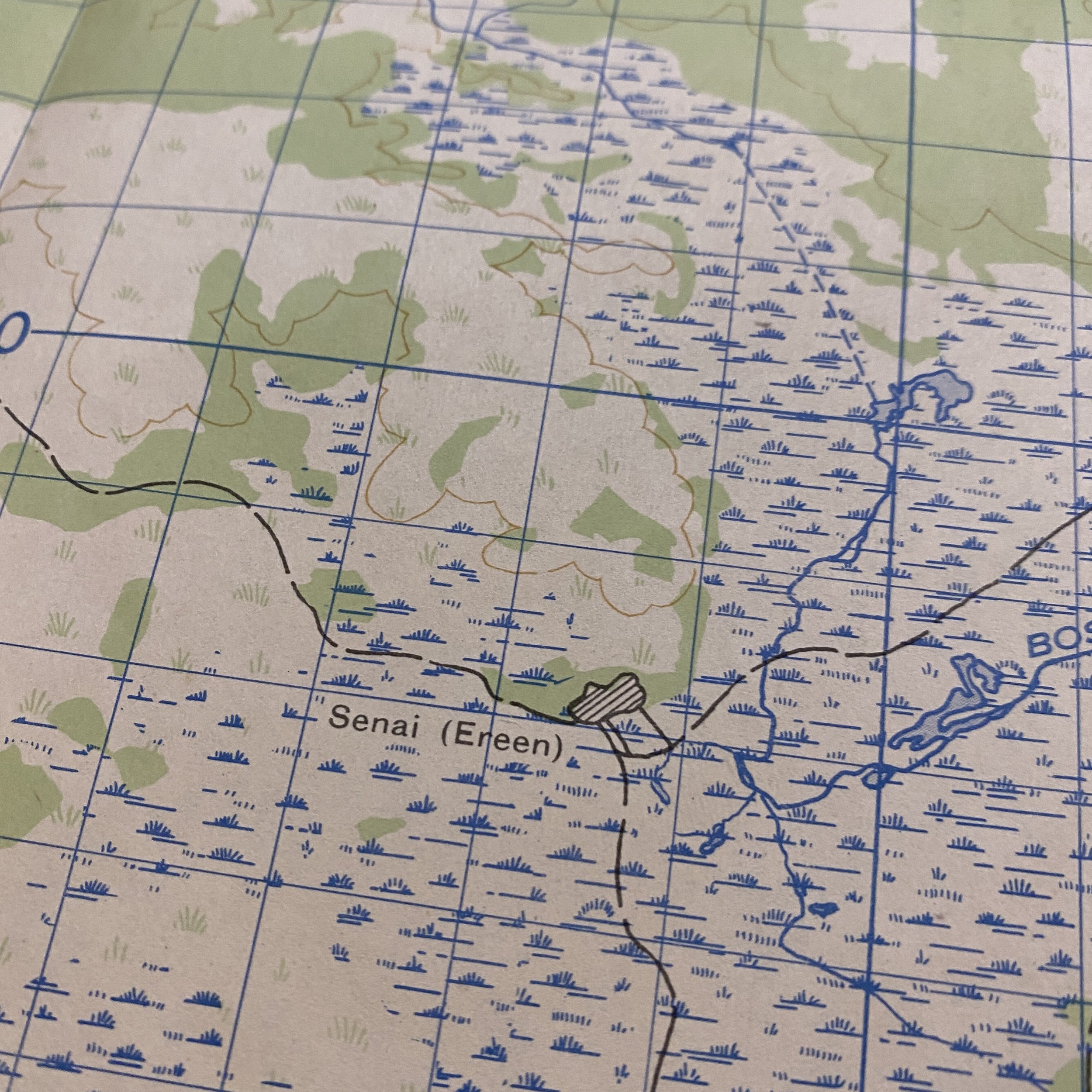

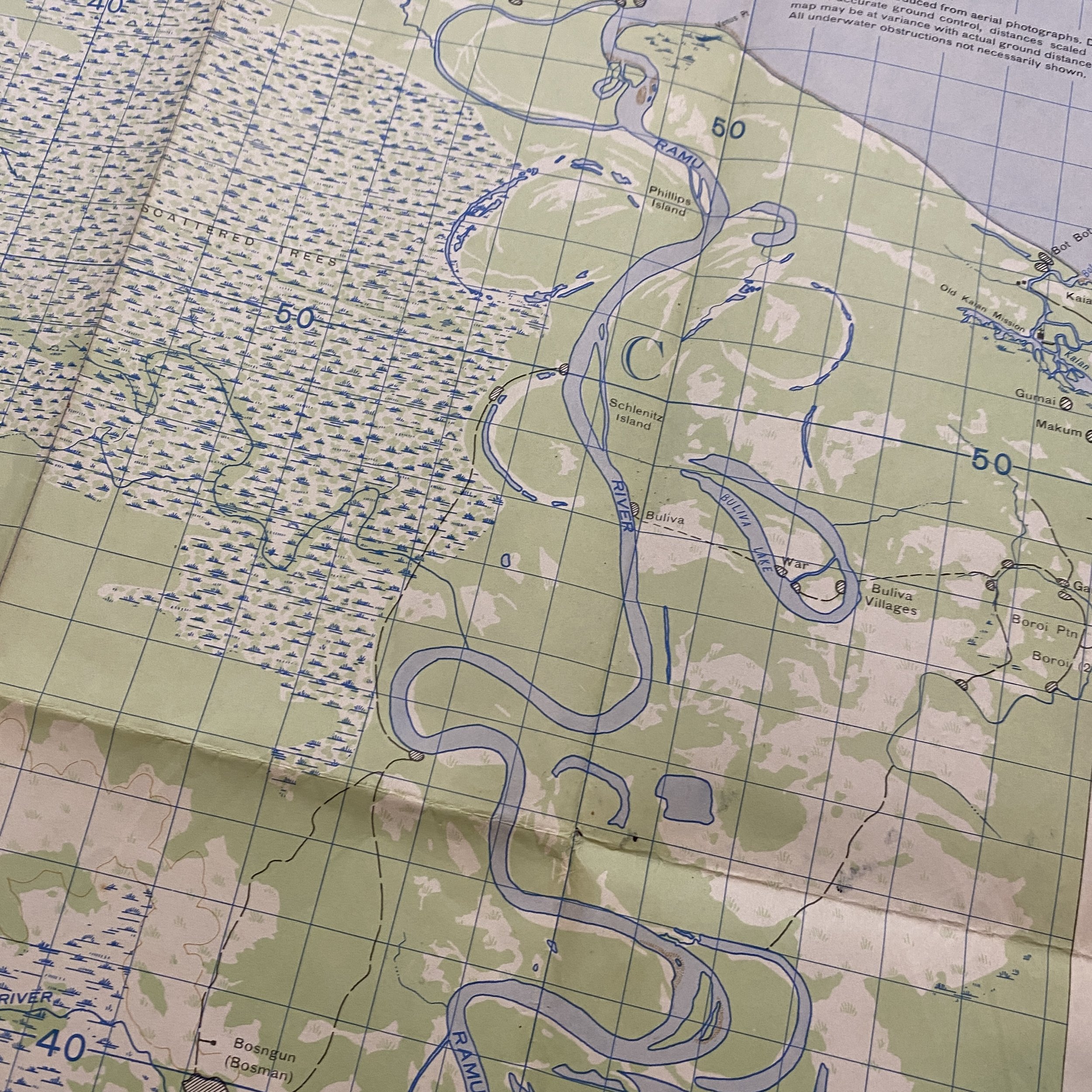

This invasion map of NUBIA WEST was used after the Allies pushed from their original landing locations at Saidor, New Guinea and attacked the Japanese on New Guinea. This map of NUBIA WEST shows very important battlefield locations such as the RAMU RIVER, located near Hansa Bay, in Madang Province, between Madang and Wewak, northeast of Bogia.

Nubia Airfield was located near Nubia village inland from Hansa Bay on the north coast of New Guinea. The Allies called this location "Nubia Airfield" for the nearby Nubia village. Known by the Japanese as "Hansa South". Today located in Madang Province in Papua New Guinea (PNG). To the north was Old Hansa Airfield and further north was Awar Airfield (Hansa North, Condor Point).

During March 1943, surveyed by the Japanese as an airfield. The 6th Airfield Construction Battalion began construction during June to October 1943 with assistance from soldiers and later the 24th Airfield Company. Together, they built a single runway measuring 3,500' x 170' (as of July 23, 1943). Another source lists the runway as 3,750' x 170' in October 23, 1943). A single taxiway and dispersal area with revetments (4 bomber, 0 fighter) was looped off the side closest to the Hansa Bay (E). A large battery of heavy anti-aircraft guns was located half way down the strip on the western side. Six heavy anti-aircraft guns were emplaced at Nubia Mission, with an additional four just north of the mission.

Used by the Japanese Army Air Force (JAAF) for use by fighters and light bombers. The 45th Sentai detachment (Ki-48 Lily) from Wewak arrived on July 30, 1943. In November 1943 designated as an emergency airfield and refueling base. During April 1943 until May 1944 attacked by Allied bombers and fighters.

American missions against Nubia

April 12, 1943 - May 3, 1944

As late as March 1944 there were still airfield personnel at the strip, mostly working to repair the runway after Allied bombing.

On June 14, 1944 Hansa Airfield area was occupied by Australian Army soldiers. Afterwards, this airfield was not repaired and was abandoned. In late June 1944, Air Technical Intelligence Unit (ATIU) investigated the Japanese aircraft wrecks at the airfield noting Ki-48 Lily 1258 and Ki-48 Lily 1199 plus the wreckage of several Ki-43 Oscar

The amount of intelligence that went into producing this specific combat operations map was very intensive which makes this a very valuable map used during the battles.

Landing at Saidor order of battle:

The ships and landing craft were escorted by the destroyers USS Beale, Mahan, Drayton, Lamson, Flusser, Reid, Smith and Hutchins. The force arrived at Dekays Bay before dawn on 2 January 1944 to find the shore obscured by low hanging clouds and drizzling rain. Admiral Barbey postponed H-Hour from 06:50 to 07:05 to provide more light for the naval bombardment, and then to 07:25 to allow the landing craft more time to form up. The destroyers fired 1,725 5-inch rounds, while rocket-equipped LCIs fired 624 4.5-inch rockets. There was no concurrent aerial bombardment, but Fifth Air Force B-24 Liberators, B-25 Mitchells and A-20 Havocs bombed Saidor airstrip later that morning.

The first wave reached the shore at about 07:30. The first four waves of Landing Craft, Personnel (Ramped) (LCP(R)) from the APDs—arrived over the next 15 minutes. Each of the six LSTs in the assault towed a Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM) of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade; two carried bulldozers, two carried rocket equipped DUKWs, and two carried spare diesel fuel. The LCMs beached shortly before 08:30 and the LSTs soon after. The Shore Battalion, 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment laid Australian Reinforcing Company (ARC) mesh to provide a roadway across the beach for vehicles.

All six LSTs were unloaded by 11:45. There was little opposition. Eleven Japanese soldiers were killed by the naval bombardment or assault troops. Perhaps as many as 150 transient Japanese troops were in the Saidor area, all of whom fled into the interior. American casualties on the day of the landing came to one soldier killed and five wounded, and two sailors drowned. Nine Japanese Nakajima Ki-49 (Helen) aircraft, escorted by up to twenty A6M Zero (Zeke) and Kawasaki Ki-61 (Tony) fighters bombed the beach area at 1630. There were three more air raids during the night, and 49 over the course of the month, but most were small.

MacArthur announced the landing in his communiqué the next day:

We have seized Saidor on the north coast of New Guinea. In a combined operation of ground, sea and air forces, elements of the Sixth Army landed at three beaches under cover of heavy air and naval bombardment. The enemy was surprised both strategically and tactically and the landings were accomplished without loss. The harbour and airfields are in our firm grasp. Enemy forces on the north coast between Sixth Army and the advancing Australians are trapped with no source of supply and face disintegration and destruction.

Japanese Response at Saidor:

Since October 1943, the Japanese strategy had been to conduct a fighting withdrawal in the face of MacArthur's advance that would "trade position, to the end that the enemy offensive will be crushed as far forward as possible under the accumulation of losses". At General Hitoshi Imamura's Japanese Eighth Area Army headquarters at Rabaul, the staff debated whether the 20th and 51st Divisions should attack Saidor or slip past it and join up with the rest of the Eighteenth Army at Wewak. In view of the poor condition of the 20th and 51st Divisions, Imamura relieved the Eighteenth Army of responsibility for the Sio area and ordered Adachi to withdraw to Madang.

Adachi had flown from Madang to the 51st Division's headquarters at Kiari in late December, and he received word of the landing at Saidor shortly before heading overland to the 20th Division's headquarters at Sio, where he received Imamura's orders. He placed Lieutenant General Hidemitsu Nakano of the 51st Division in overall command of the forces east of Saidor and ordered the 41st Division to move from Wewak to Madang to defend that area. He then departed for Madang by submarine. To harass Saidor, he withdrew eight companies from Major General Masutaro Nakai's force facing Major General Alan Vasey's Australian 7th Division in the Finisterres. The Nakai force deployed along the Mot River around Gambumi. It succeeded in repelling American attempts to cross the river until 21 February, when it withdrew, its mission complete. However, weakening the Finisterres front provoked an Australian attack, resulting in the loss of the entire Kankirei position.

Nakano organised the withdrawal of his force. He chose two routes, one following the coast and the other running along the ridge lines of the foothills of the Finisterres. Initially, the 20th Division was to take the coastal route while the 51st and some naval units took the inland one, but this was changed at the last minute and both divisions took the inland route. Additional rations and supplies were to be delivered by submarine. However, the 51st Division elected to move out rather than wait for the submarines and risk exhausting its rations through waiting. The 51st Division had experience crossing the mountains before, and Nakano was confident of its ability to negotiate them. In the event, one submarine was discovered by Allied aircraft and failed to reach its objective, while a second was discovered and sunk. A third got through but it was a small type that was only able to carry five tons of supplies, which were distributed among units of the 20th Division.

The difficulty of the march had been underestimated, and sick and wounded men had to make their way through trackless regions. Lieutenant General Kane Yoshihara, the Chief of Staff of the Eighteenth Army, recalled the march:

The most wearing part was that with these ranges, when they climbed to the craggy summit they had to descend and then climb again, and the mountains seemed to continue indefinitely, until they were at the extreme of exhaustion. Especially when they trod the frost of Nokobo Peak they were overwhelmed by cold and hunger. At times they had to make ropes out of vines and rattan and adopt "rock-climbing" methods; or they crawled and slipped on the steep slopes; or on the waterless mountain roads they cut moss in their potatoes and steamed them. In this manner, for three months, looking down at the enemy beneath their feet, they continued their move. Another thing which made the journey difficult was the valley streams, which were not usually very dangerous. At times, however, there was a violent squall, for which the Finisterres are famous during the rainy season; then these valley streams for the time being flowed swiftly and became cataracts. Then there were many people drowned ... Lieutenant General Ryoichi Shoge was swept away by one of these streams on one occasion but fortunately managed to grasp the branch of a tree which was near the bank and was able to save one of his nine lives.

The first troops reached Madang on 8 February, and the whole movement was complete by 23 February. Eighteenth Army anticipated that units reaching Madang, would probably have lost much of their equipment, as was indeed the case, so stores were gathered together from distant Wewak and Hansa, and collected together near Madang. In addition emergency articles such as some food, shoes and clothing were collected near the mouth of the Minderi River, supplied by the Nakai Detachment.