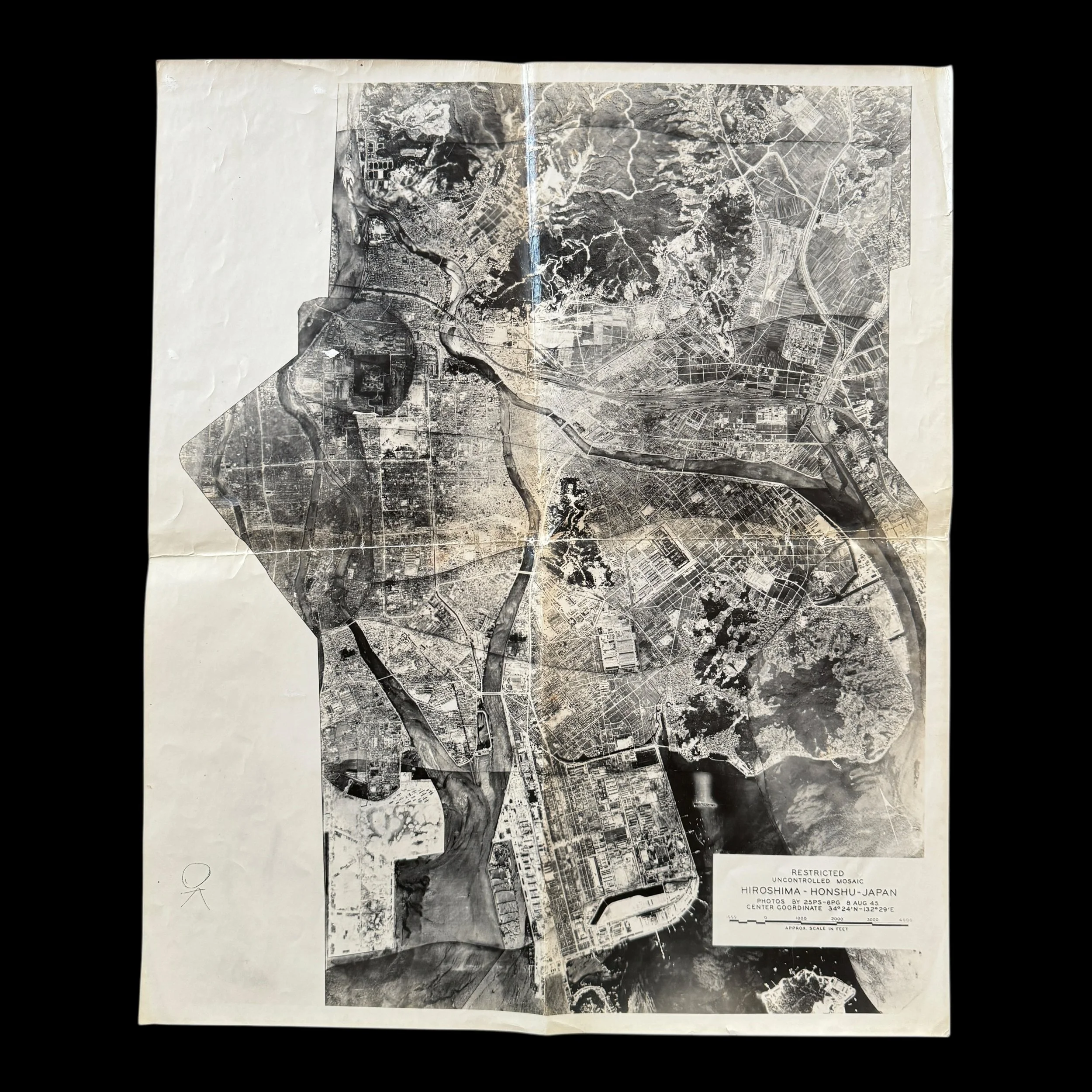

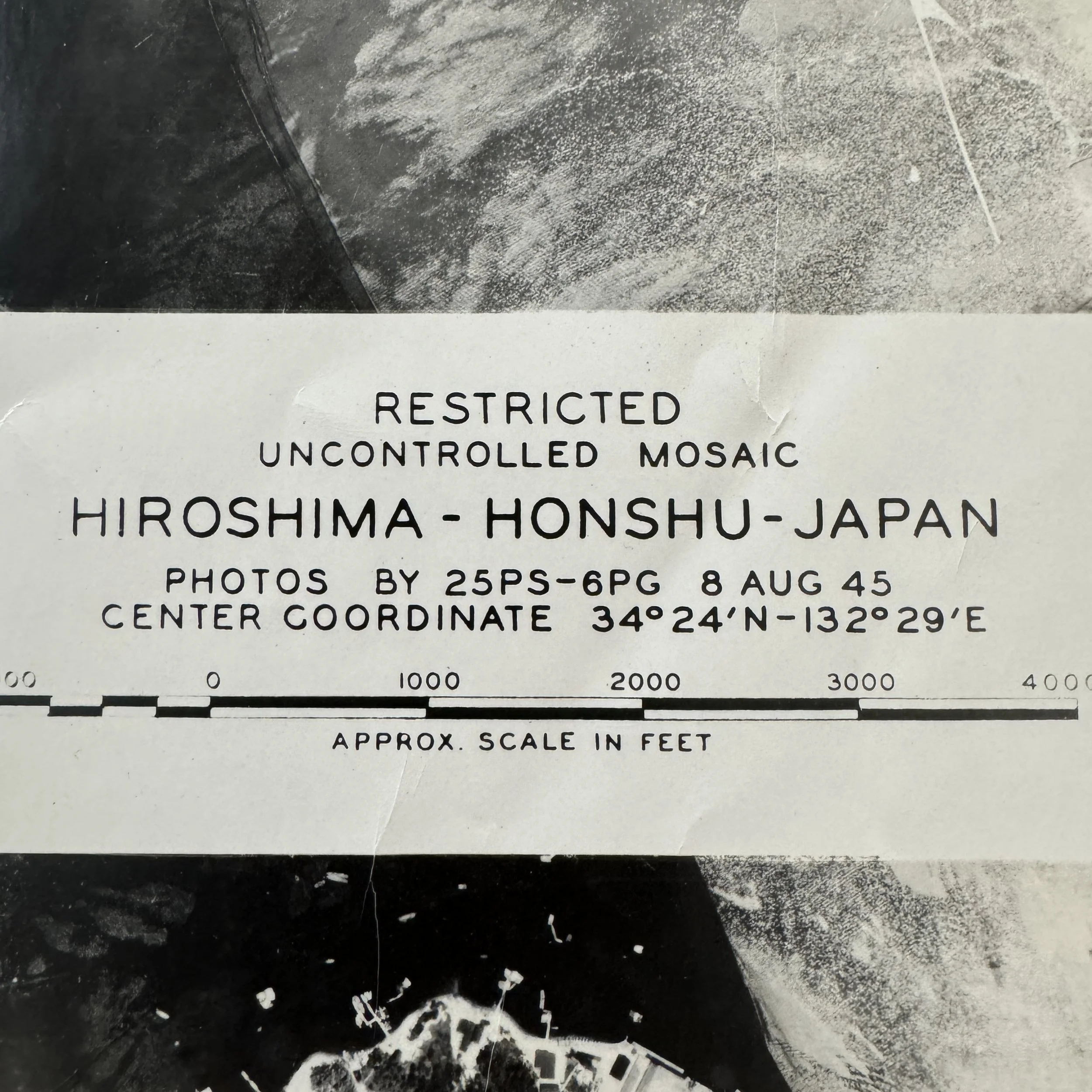

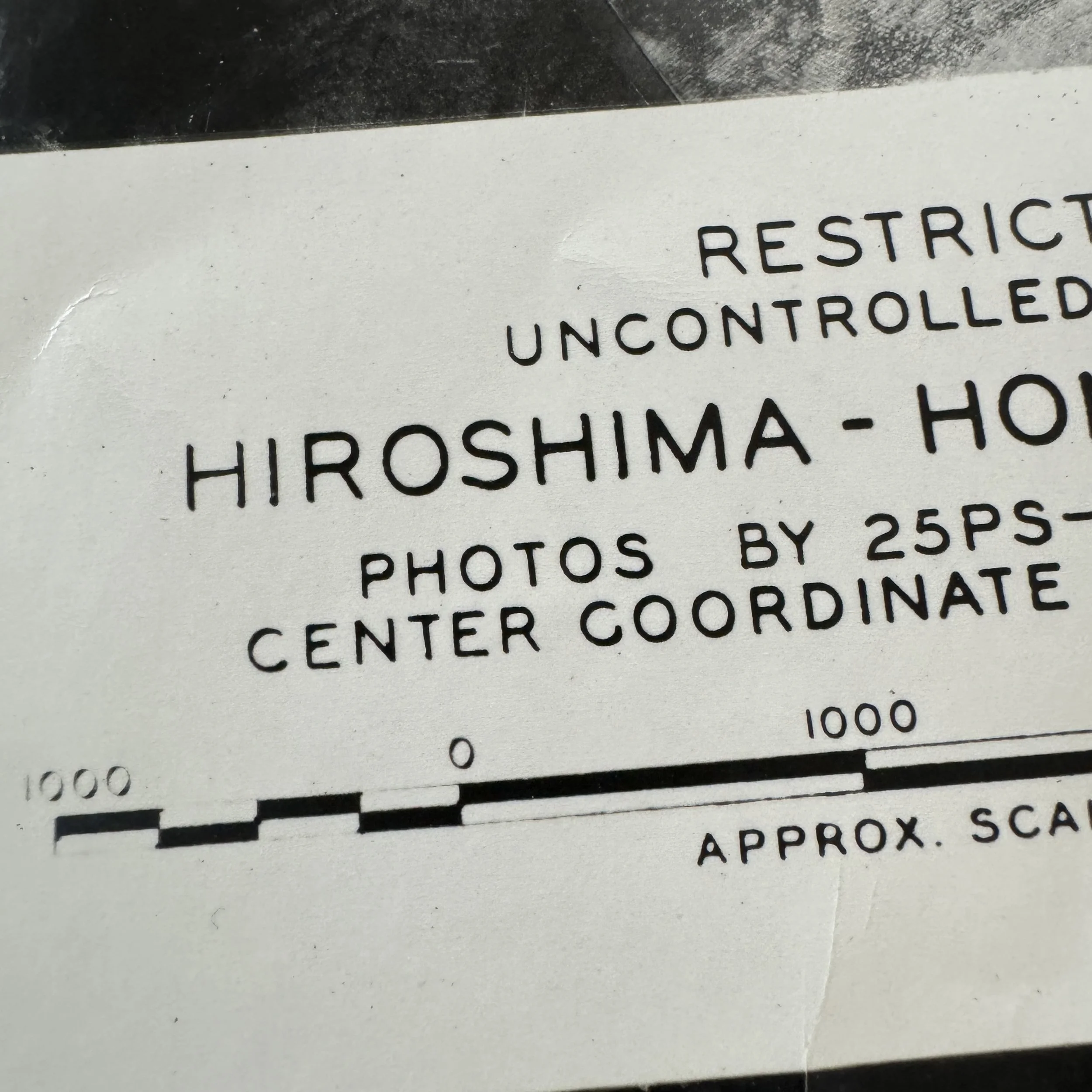

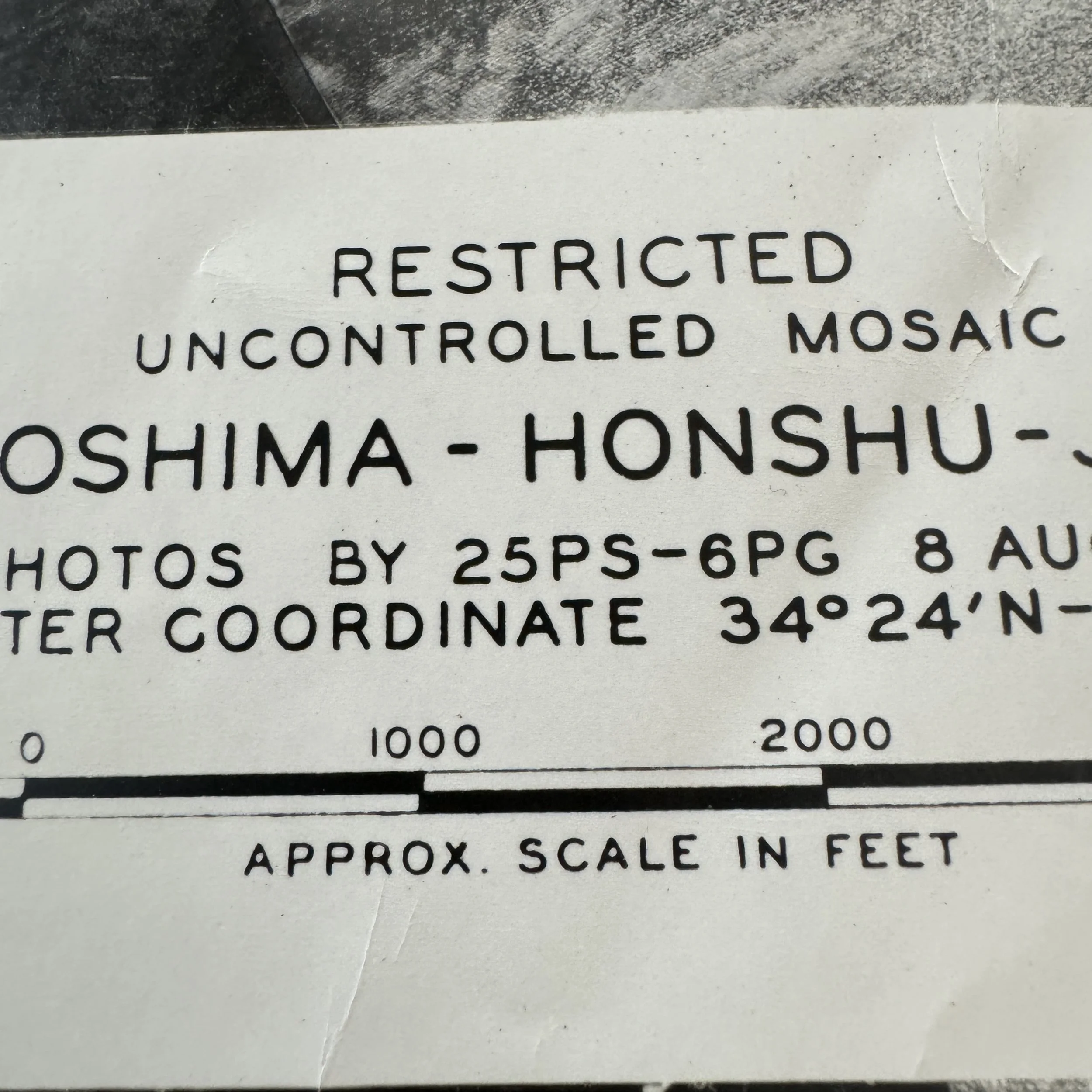

Extremely Rare Original WWII August 8, 1945 “RESTRICTED” Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Aerial Reconnaissance Mosaic by the 25th Photo Recon Squadron, 6th Photo Group (First Post-Bombing Military Intelligence)

Extremely Rare Original WWII August 8, 1945 “RESTRICTED” Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Aerial Reconnaissance Mosaic by the 25th Photo Recon Squadron, 6th Photo Group (First Post-Bombing Military Intelligence)

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

From: World War II

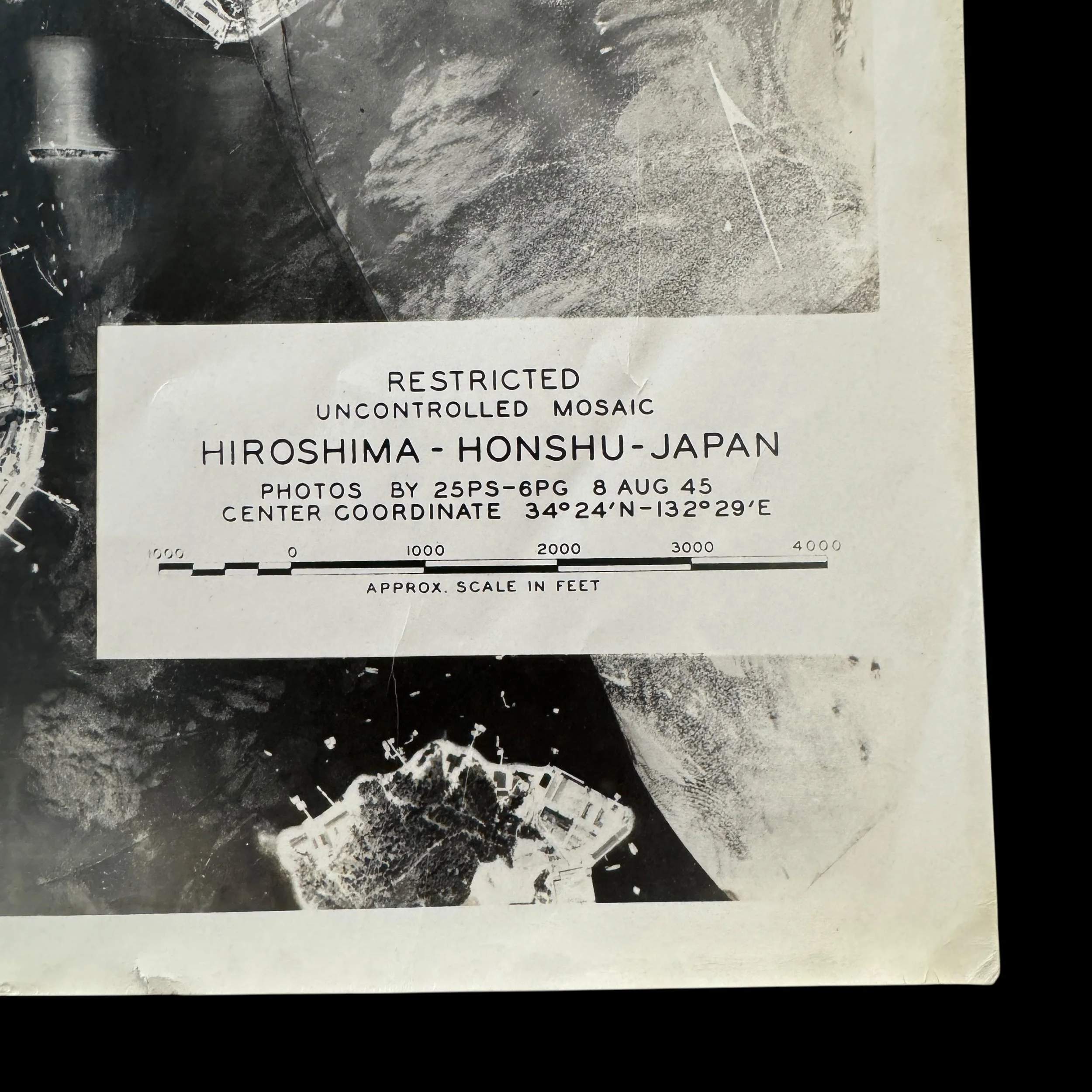

Type: Extremely Rare Original WWII August 8, 1945 “RESTRICTED” Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Aerial Reconnaissance Mosaic by the 25th Photo Recon Squadron, 6th Photo Group – First Post-Bombing Military Intelligence Survey

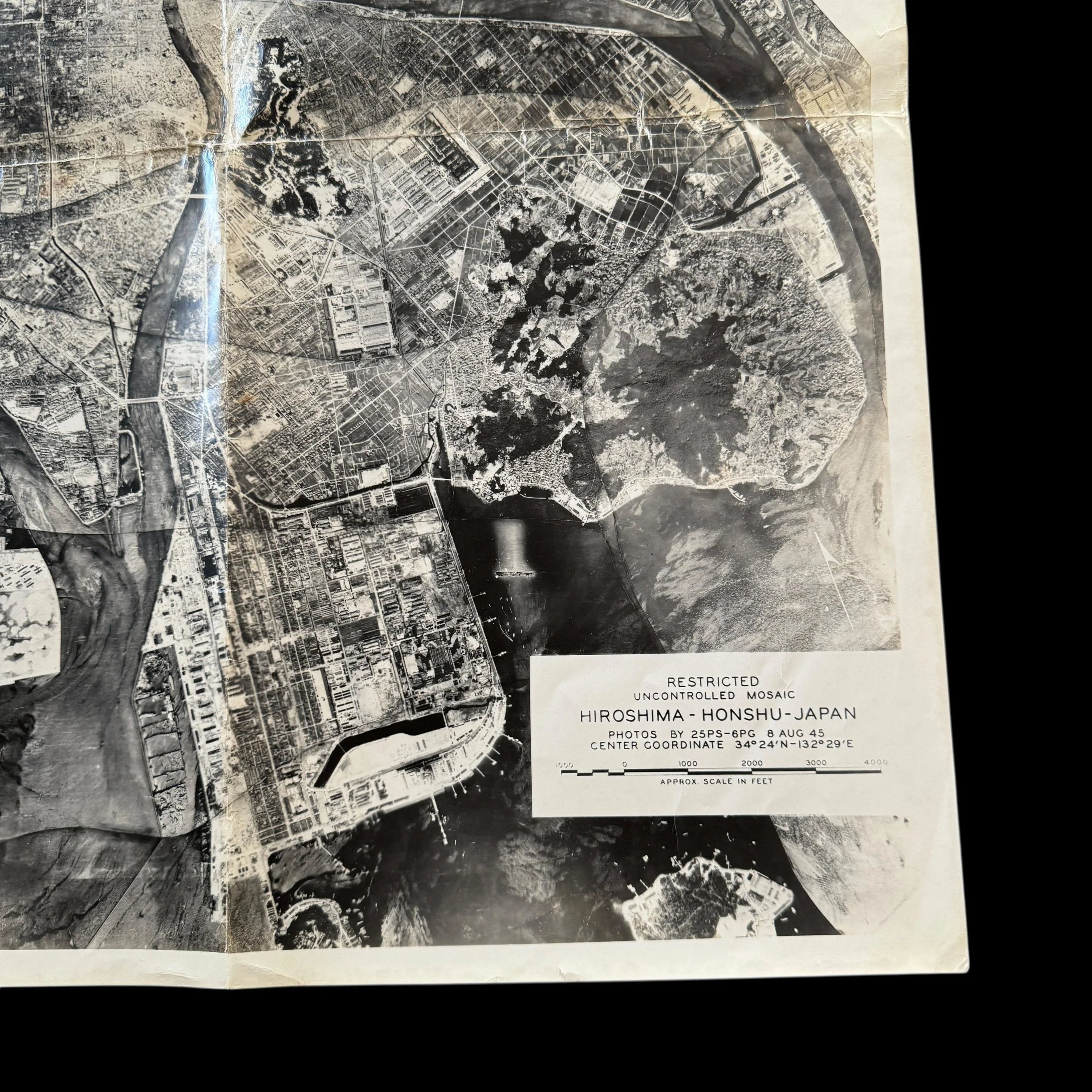

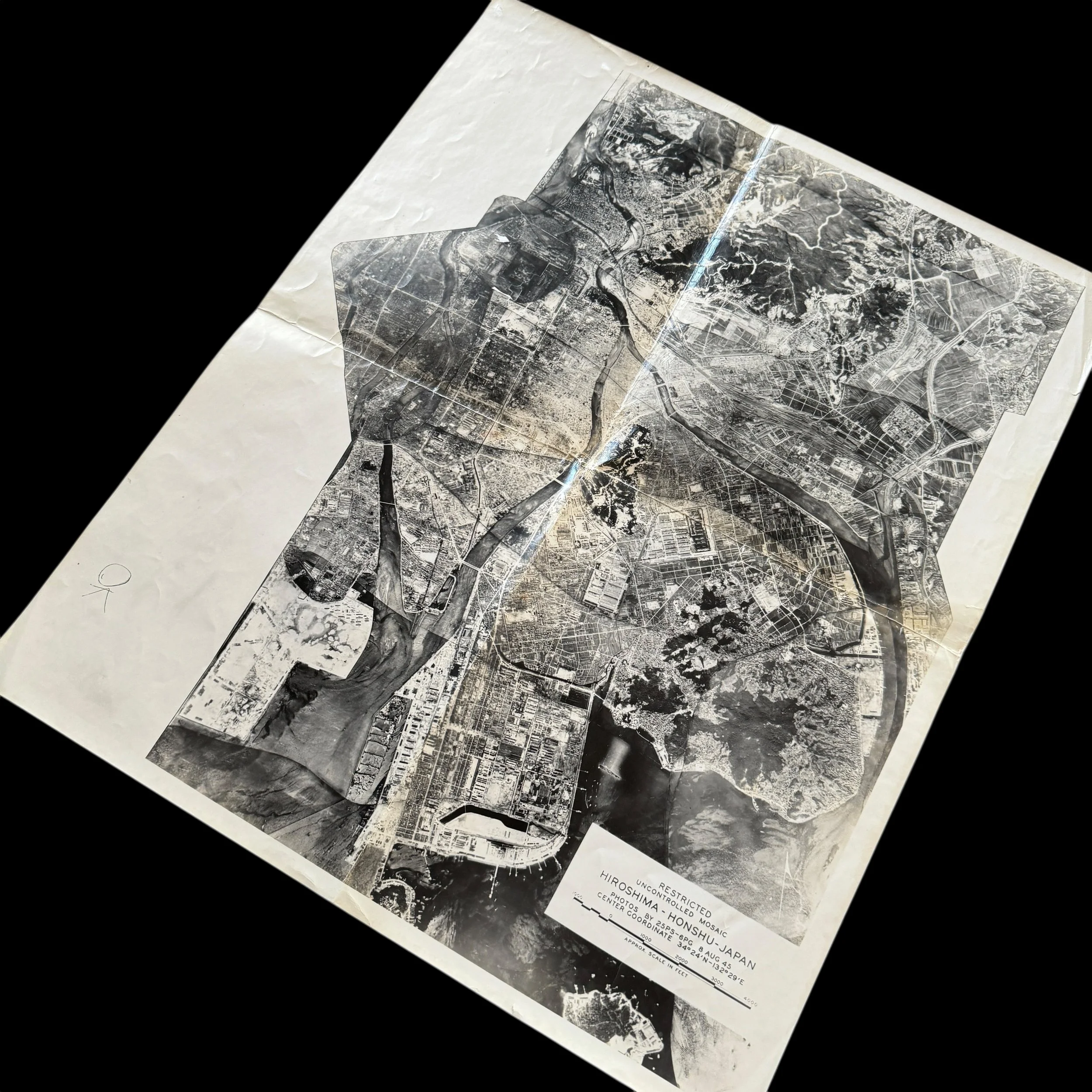

Size: 20 × 24 inches

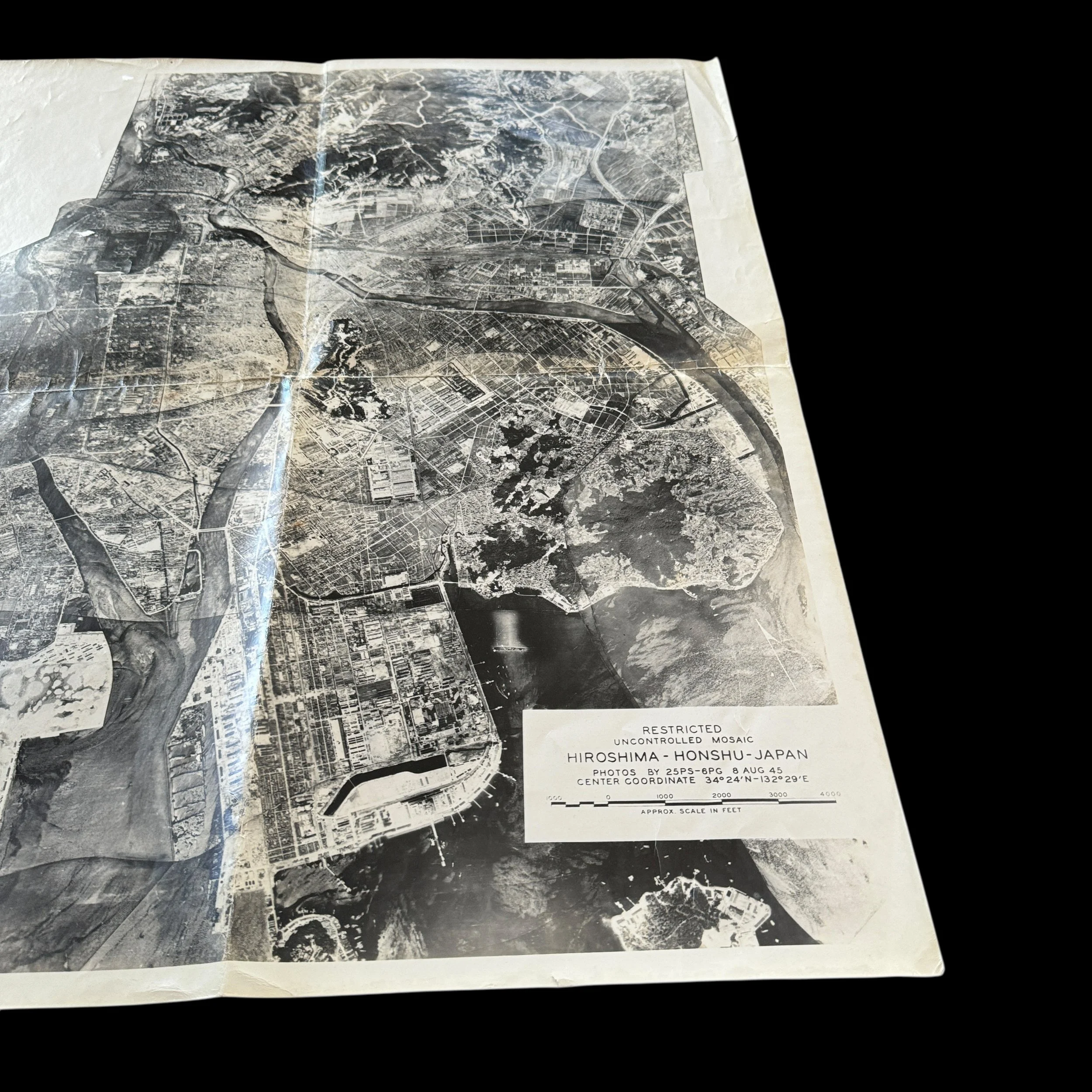

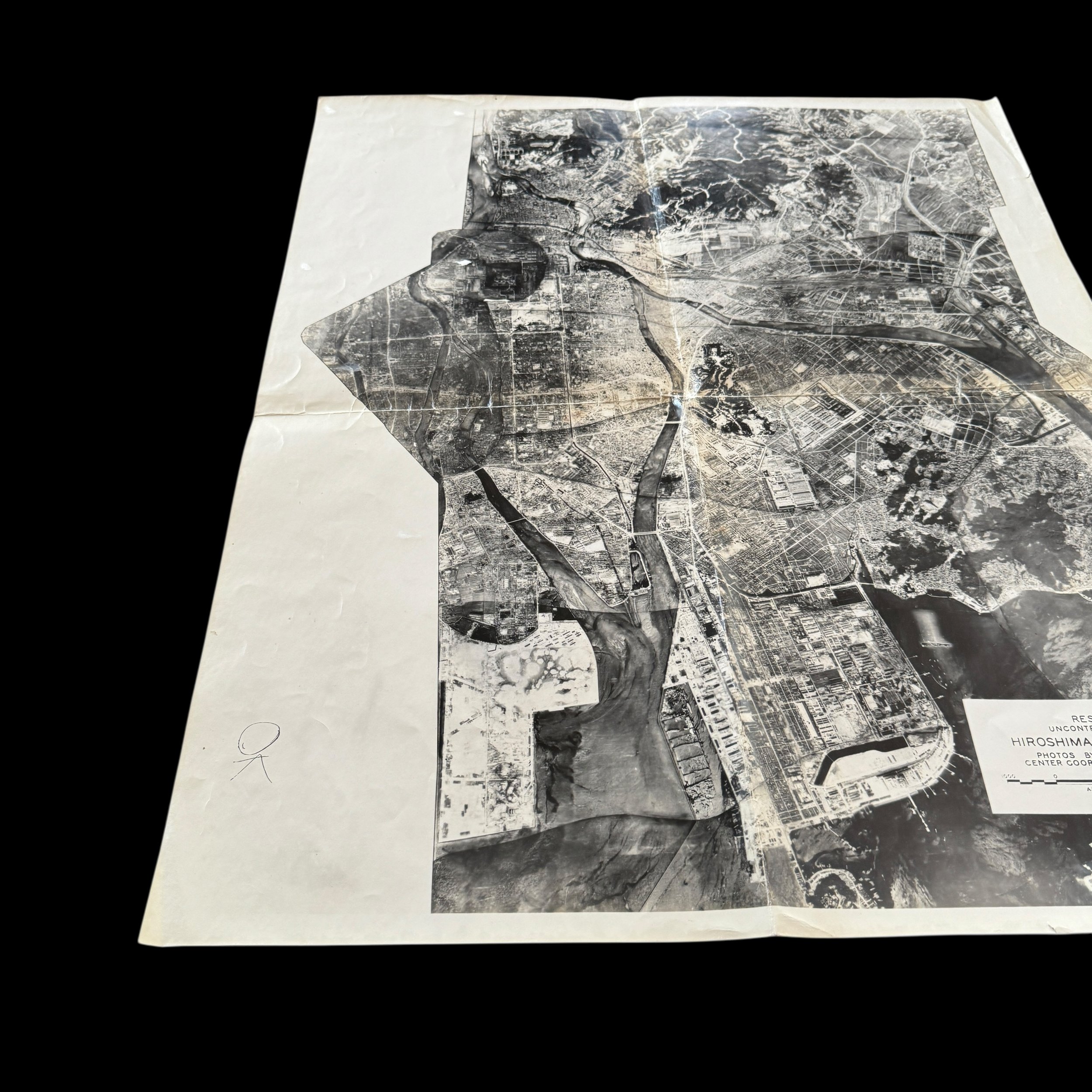

This once-in-a-lifetime and museum grade World War II artifact is one of the first “RESTRICTED” uncontrolled military intelligence mosaics of Hiroshima, created just two days after the first atomic bomb was dropped. Dated August 8, 1945, this mosaic was meticulously compiled from aerial reconnaissance photographs taken by the 25th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron of the 6th Photo Group—making it one of the earliest and most sensitive visual intelligence assessments ever produced of an atomic aftermath. At the time, the United States had just initiated an unprecedented form of warfare. On August 6, 1945, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay dropped “Little Boy,” the world’s first wartime atomic bomb, over Hiroshima at precisely 8:15 a.m. The result was instantaneous devastation—flattening over five square miles of the city and killing tens of thousands in seconds.

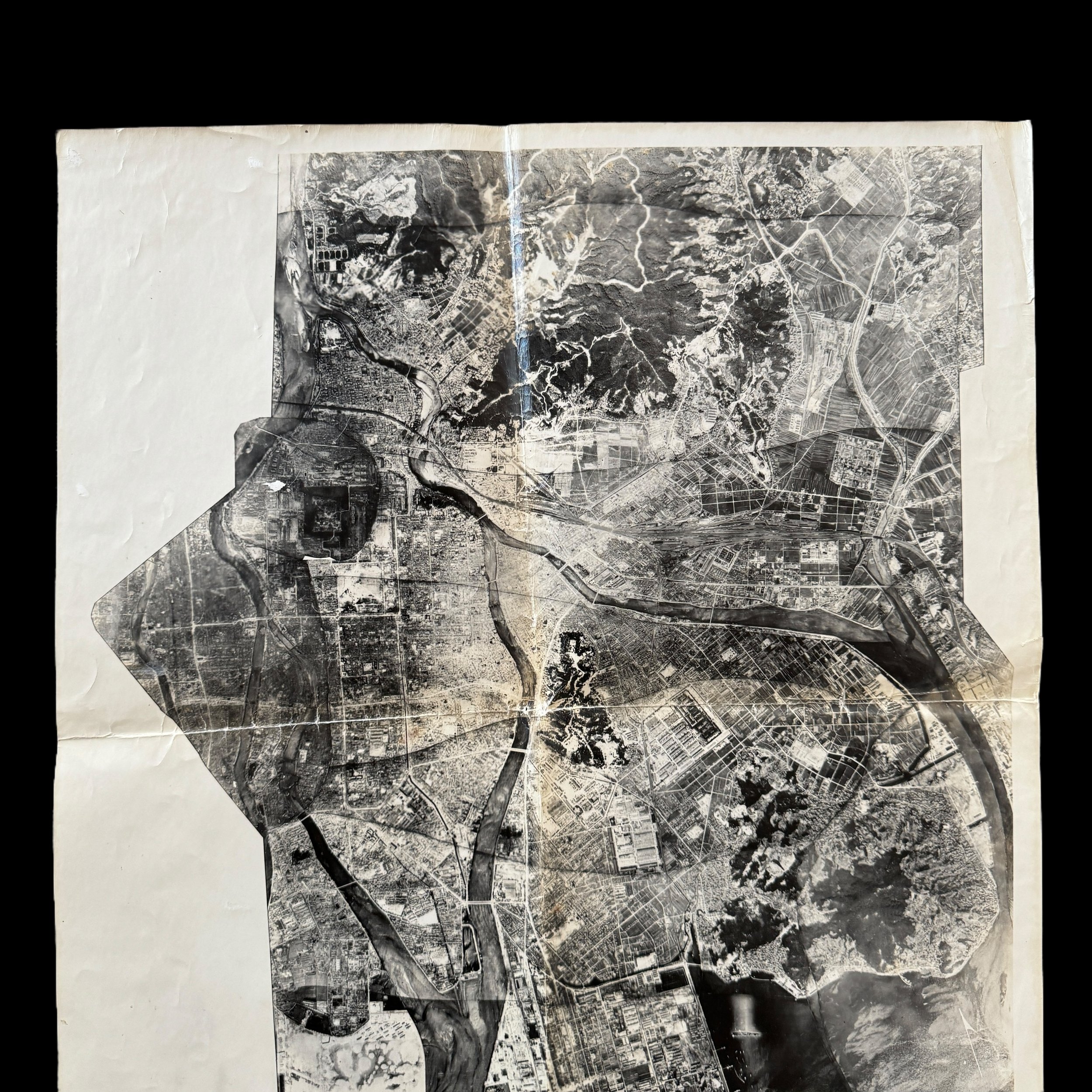

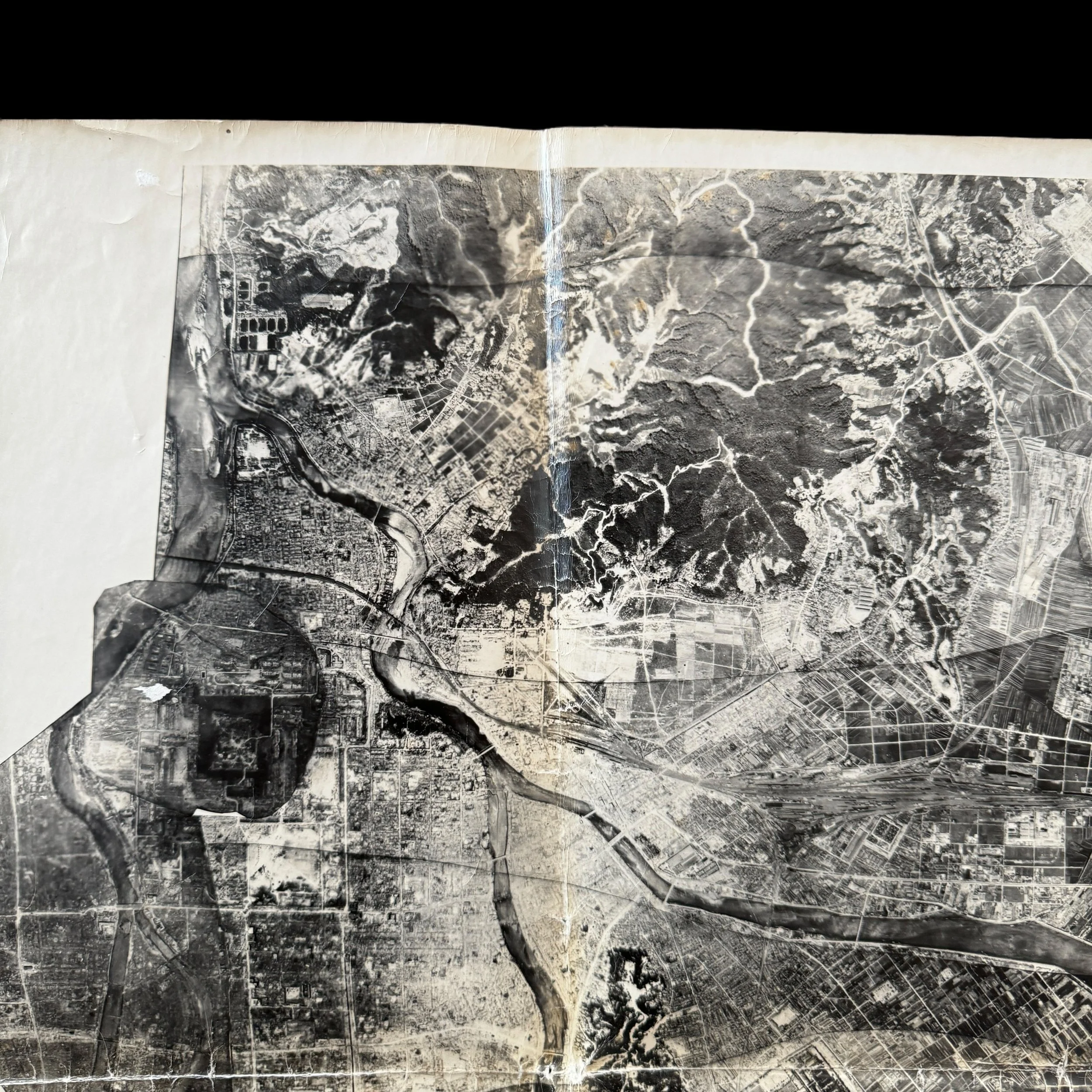

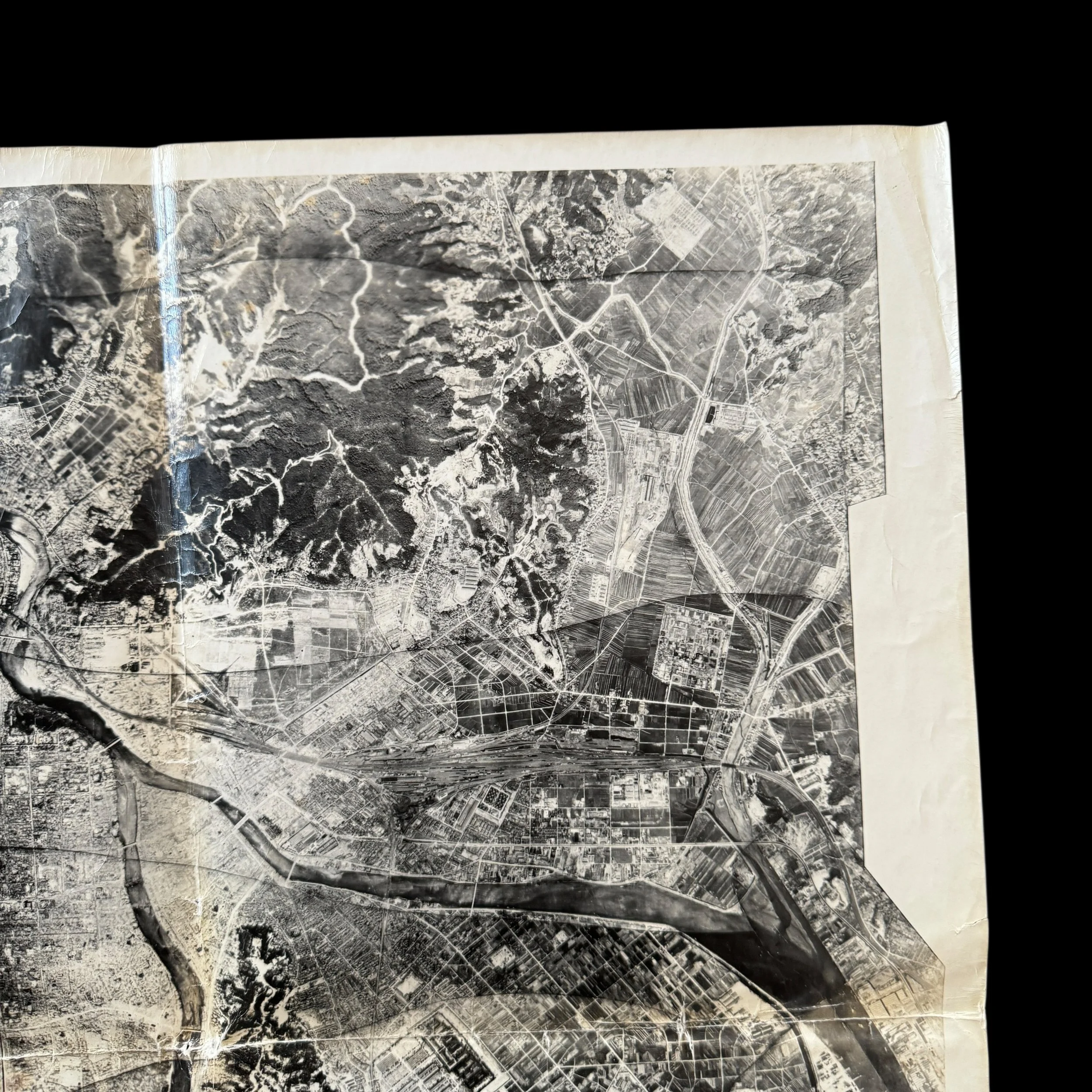

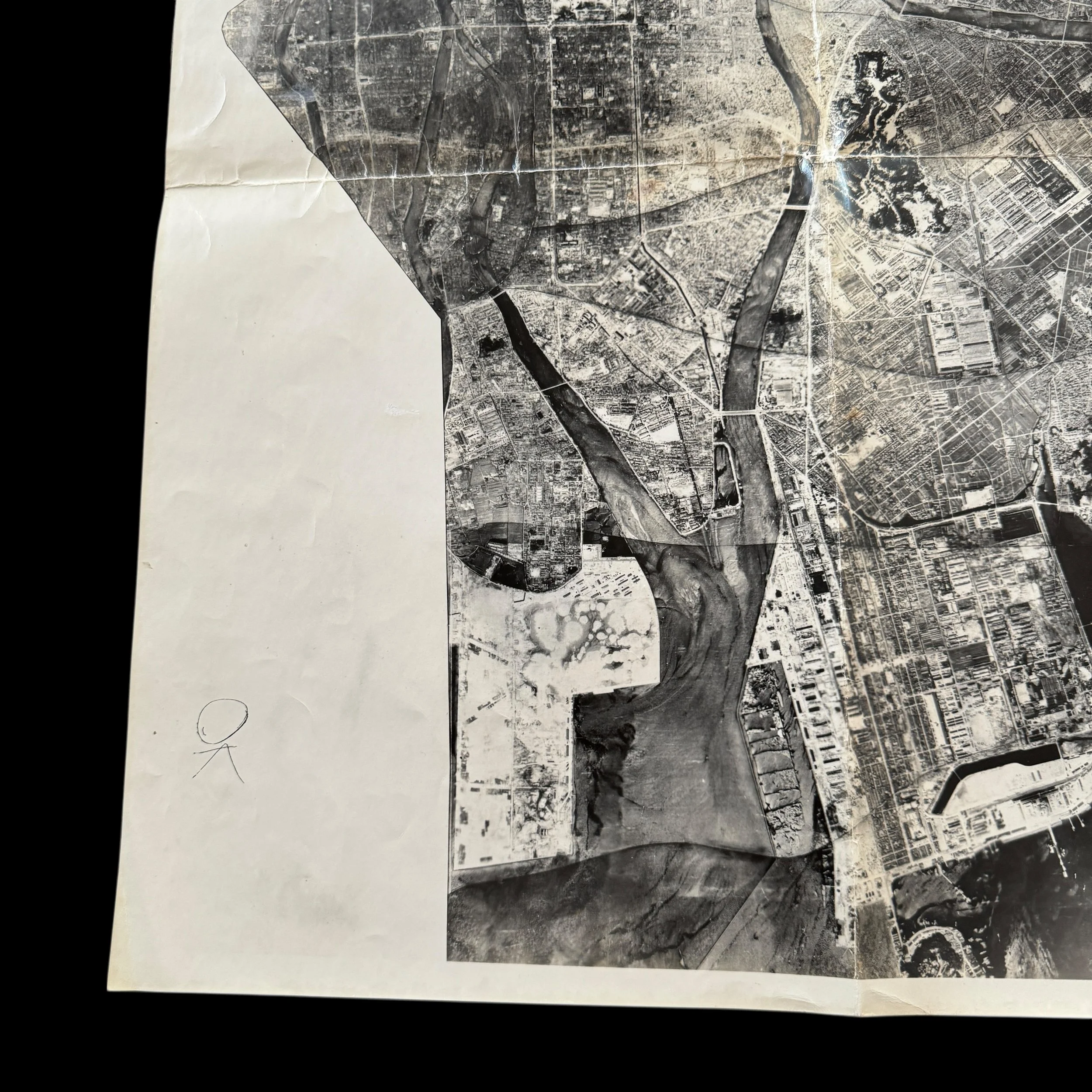

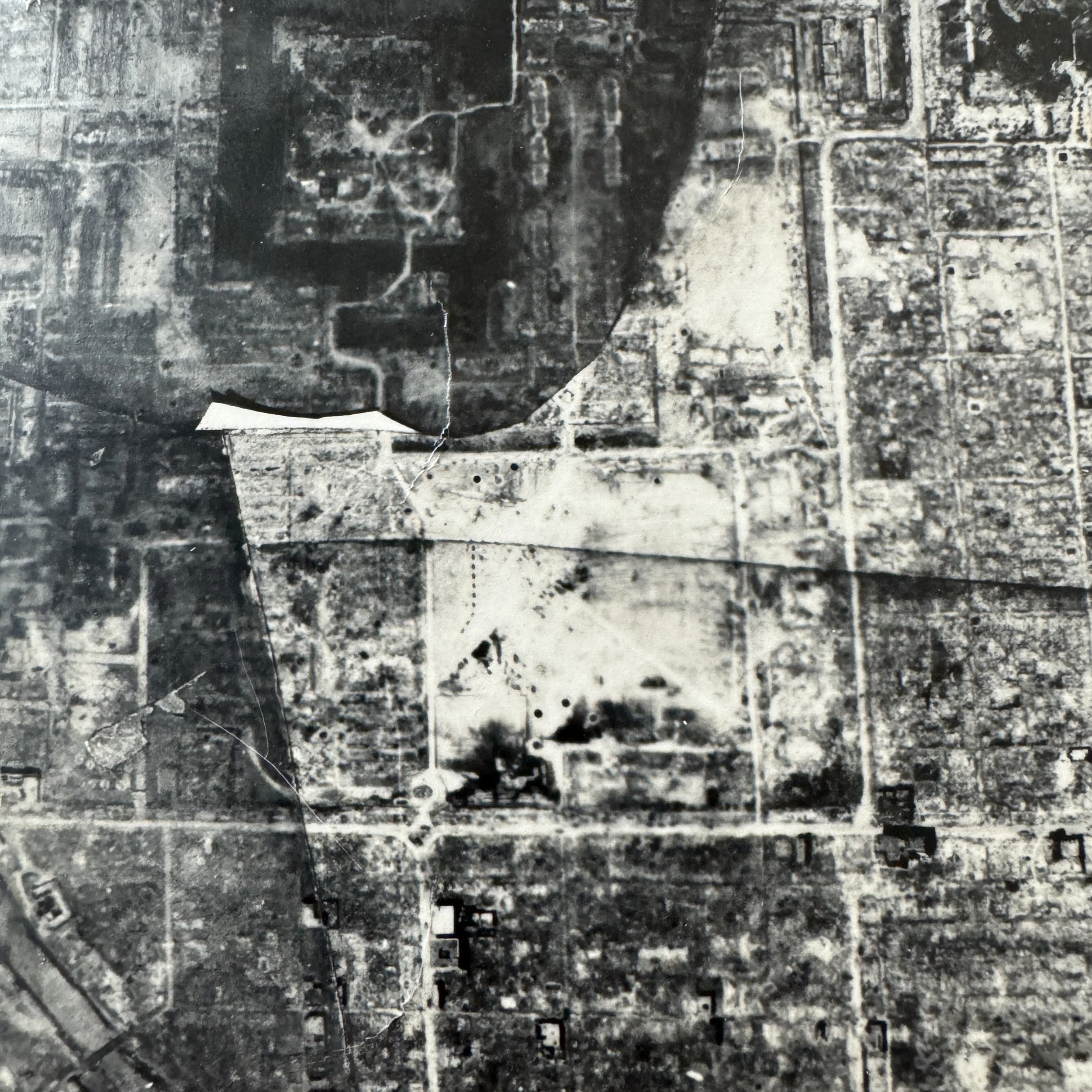

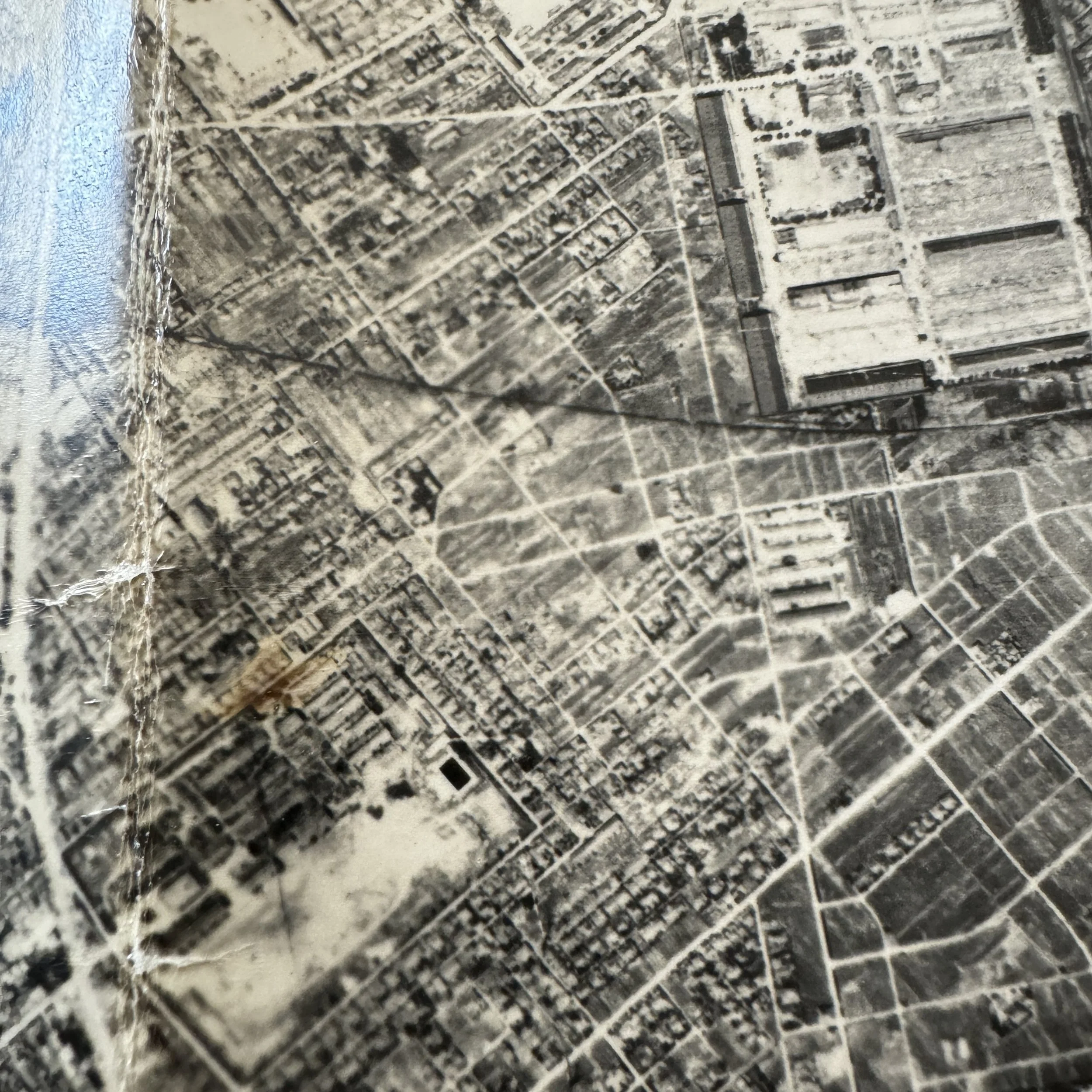

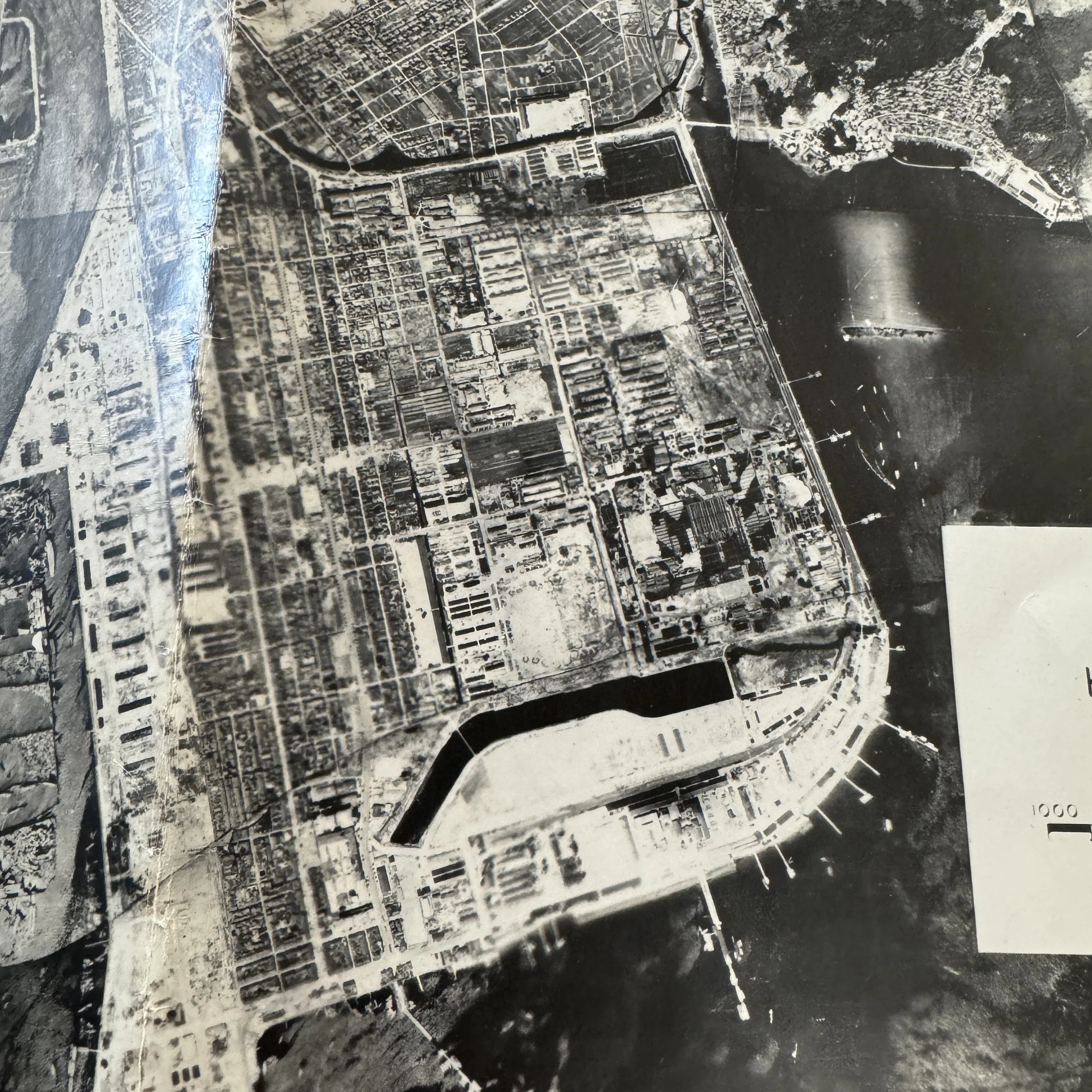

The immediate aftermath made reconnaissance nearly impossible. A thick column of smoke, dust, and radioactive debris hovered over the city. Fires raged for hours. Yet within 48 hours, with aerial conditions improving slightly, the U.S. military launched high-priority photographic missions to assess the damage. Reconnaissance aircraft—most likely F-13 Superfortress variants outfitted with long-range aerial cameras—captured overlapping, high-resolution vertical images of ground zero. Upon returning to their base, likely Tinian in the Marianas, photographic analysts assembled these into what is known as an “uncontrolled mosaic,” a rapid, manual technique in which overlapping prints were cut and aligned by hand without precise geometric calibration. What resulted was a wide, panoramic photographic view of a city utterly destroyed—one that could be used by top military officials and Manhattan Project scientists to evaluate the immediate effects of the bomb’s unprecedented destructive force.

This artifact was never intended for the public. It was produced under a “RESTRICTED” classification, meaning it was only accessible to those at the highest levels of U.S. and Allied command, including members of the Manhattan Project, General Douglas MacArthur’s intelligence staff, and possibly even the President himself. Its purpose was not symbolic, but analytical. Officials needed to understand blast radii, fire patterns, building obliteration zones, and overall infrastructure collapse to assess the bomb’s effectiveness and to guide future strategy—including whether to deploy a second bomb, which they would do three days later over Nagasaki.

Visible on this mosaic are telltale signs of the immense heat and concussive force. The iconic Aioi Bridge, used as the bomb’s aiming point, stands intact in form but is surrounded by flattened earth. The banks of the Motoyasu River are choked with debris. Concentric damage rings ripple outward from ground zero. Some structural skeletons can still be seen through the ash, including the shell of what would later be preserved as the Hiroshima Peace Dome. Perhaps most chilling are the mosaic’s physical features—the seams and overlaps of individual photos, still clearly visible, showing exactly where military analysts had sliced and joined the prints. This wasn’t created for beauty. It was a rushed, highly classified tool of war analysis—assembled with urgency for generals and physicists grappling with the dawn of nuclear warfare.

The 25th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron, part of the 6th Photo Group and the Twentieth Air Force under General Curtis LeMay, had played a critical role in documenting the Pacific air war. Their shift to atomic bomb reconnaissance marked a somber turning point—the beginning of aerial photography’s role not just in war planning, but in documenting and understanding nuclear destruction. These early mosaics became foundational to later military planning, Cold War doctrine, and even post-war scientific studies into blast effects, radiation dispersion, and urban resilience.

Of the few mosaics that survived, most remain sealed in government archives or within the holdings of major national museums. Very few were printed in large format, and even fewer escaped destruction, declassification purges, or repurposing in later training. This surviving print, assembled and distributed in the final week of the war, represents not just a tangible link to one of the most pivotal moments in human history—it is also an object that helped shape the decisions that followed. It informed the dropping of the second bomb, Japan’s eventual surrender, and the onset of a nuclear world order.

Holding this artifact today is to witness history in its rawest form: the aftermath of atomic warfare viewed through the lens of military necessity, secrecy, and scientific inquiry. It remains a powerful and irreplaceable record of both devastation and the decisions that ended a world war.