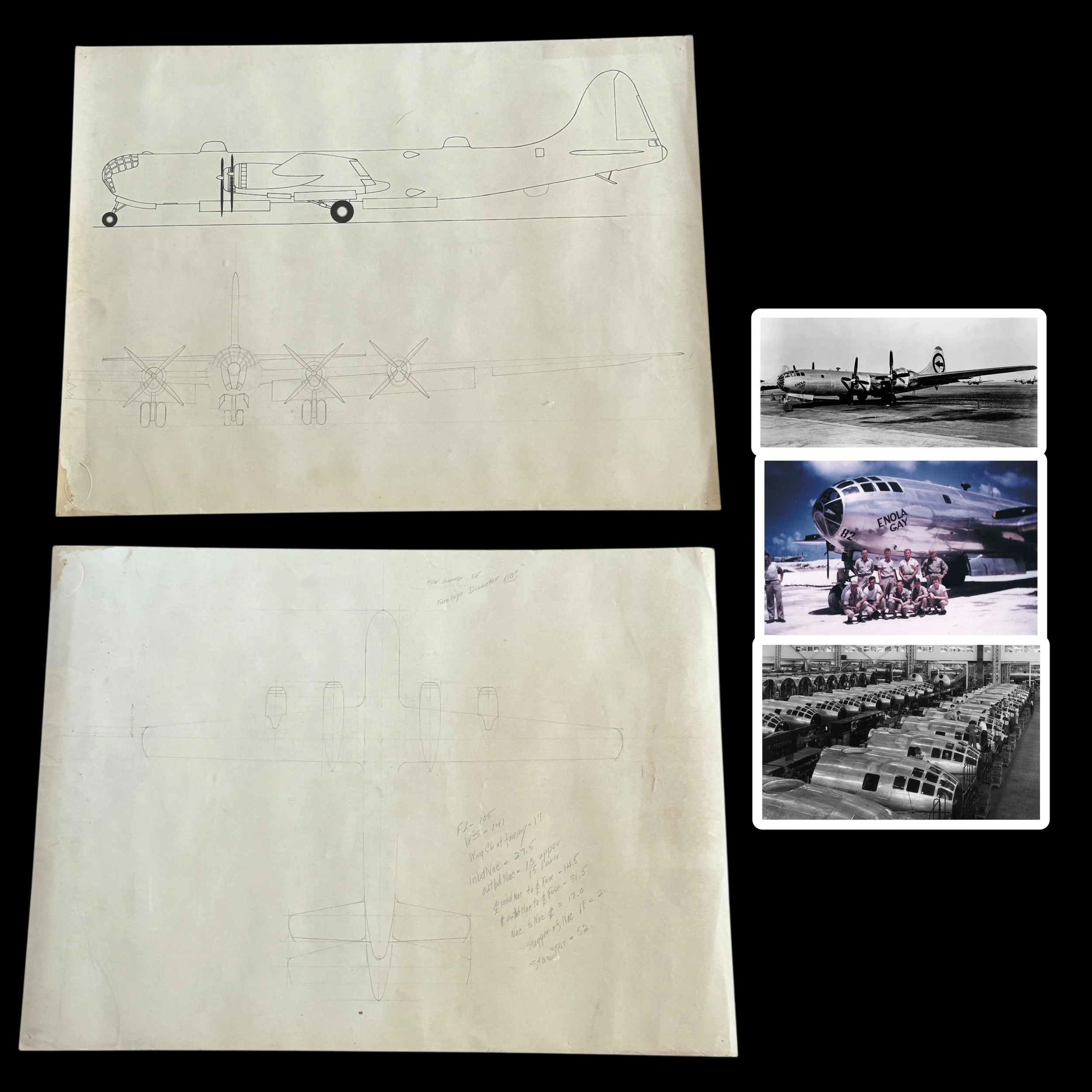

EXTREMELY RARE! Original WWII Engineer’s Hand-Drawn Boeing B-29 Superfortress Revisions Blueprint from Boeing Wichita Division "Birthplace of the Atomic Bomb Aircraft" (DOUBLE-SIDED)

EXTREMELY RARE! Original WWII Engineer’s Hand-Drawn Boeing B-29 Superfortress Revisions Blueprint from Boeing Wichita Division "Birthplace of the Atomic Bomb Aircraft" (DOUBLE-SIDED)

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

*”Wichita’s role in this process was foundational. Every aircraft used in the first bombing raid on Japan in June 1944 was built there. The most historically significant of them all—the Enola Gay—was rolled out of Boeing’s Wichita plant and later modified under the Silverplate program. On August 6, 1945, Colonel Paul Tibbets and his crew flew the Enola Gay from Tinian Island to Hiroshima, where they released Little Boy—the first atomic weapon ever used in warfare. Just three days later, Bockscar, another Silverplate-modified B-29, dropped Fat Man on Nagasaki. The devastating effectiveness of these missions—both launched from B-29s—ushered in the nuclear age and forced Japan’s surrender, effectively ending the war.”

From: World War II

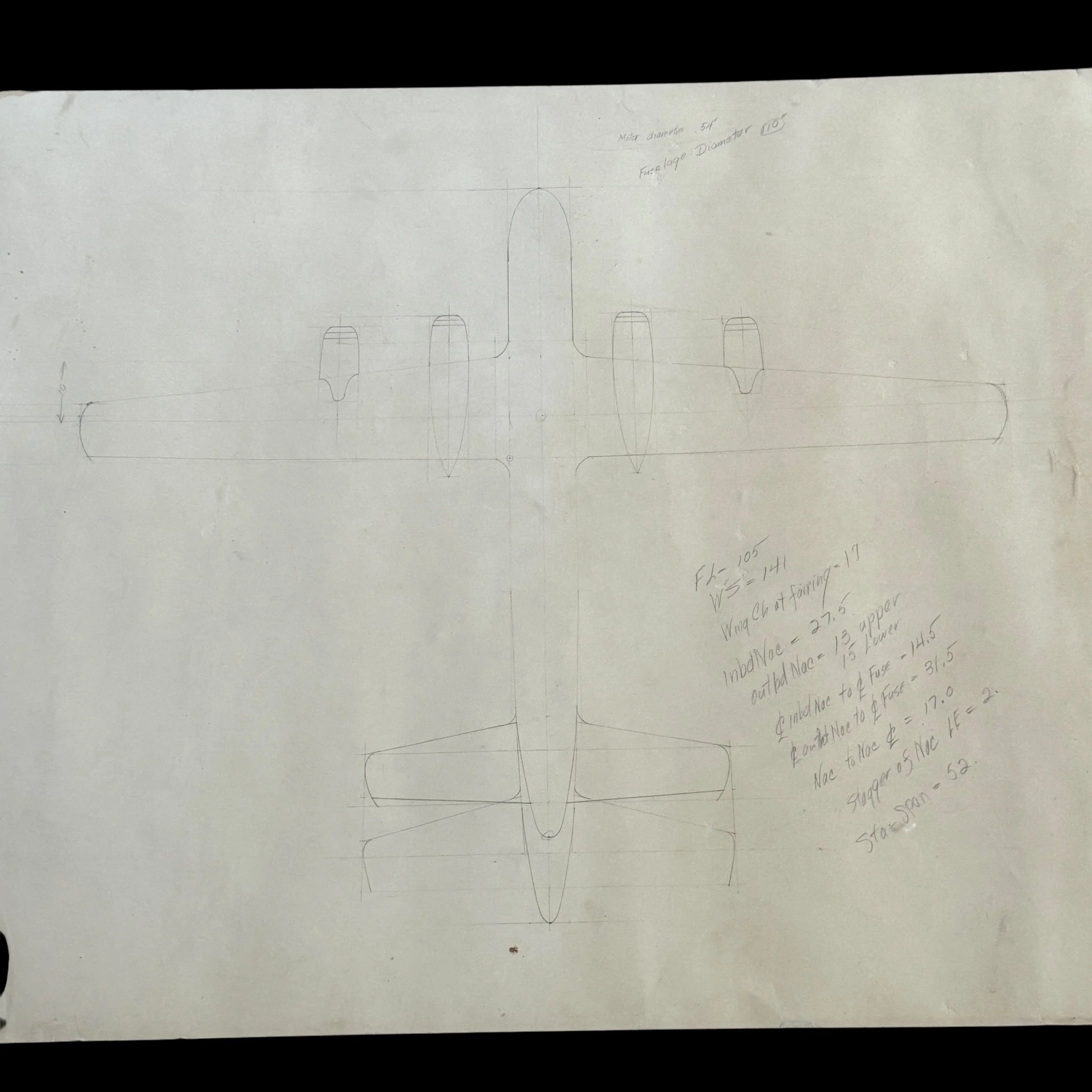

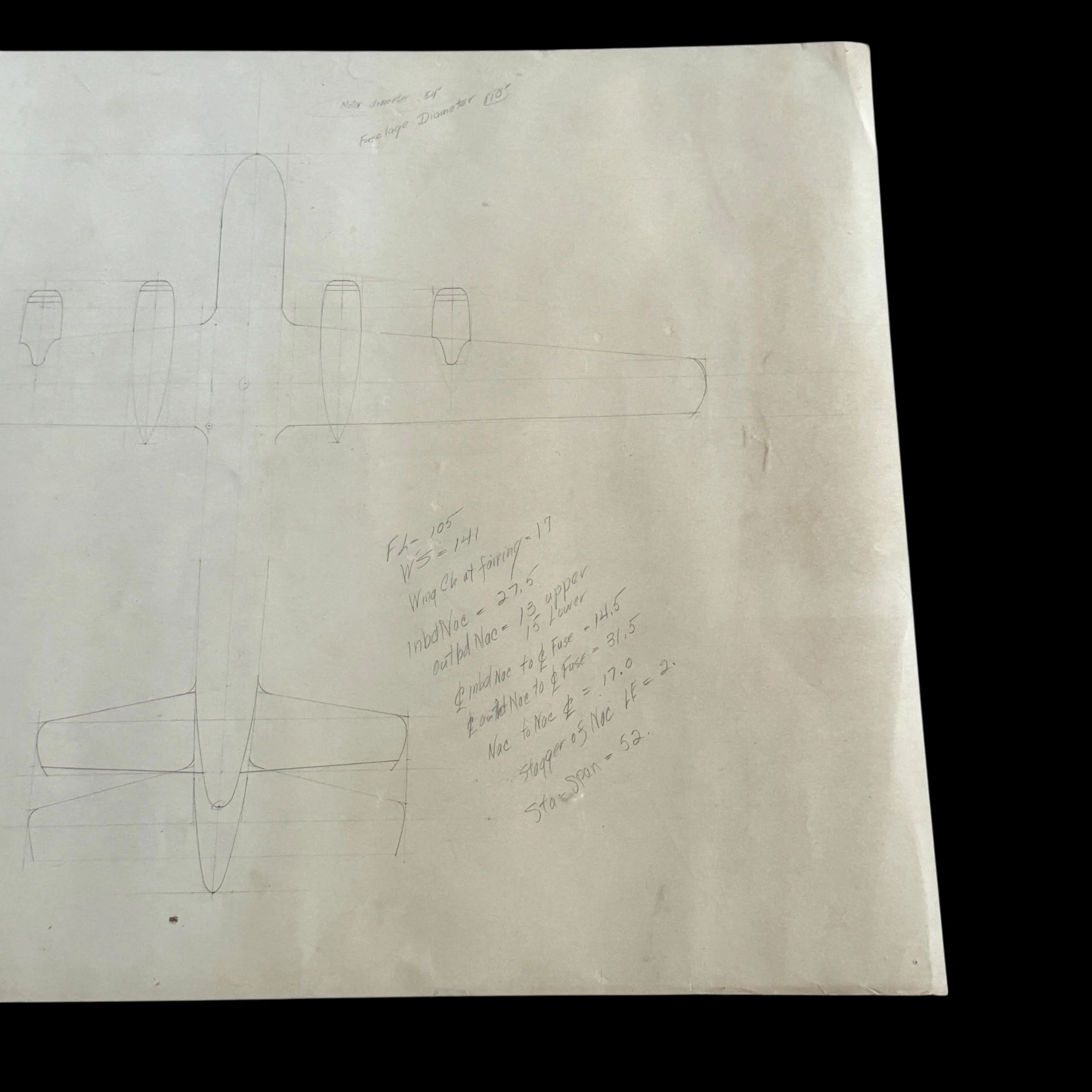

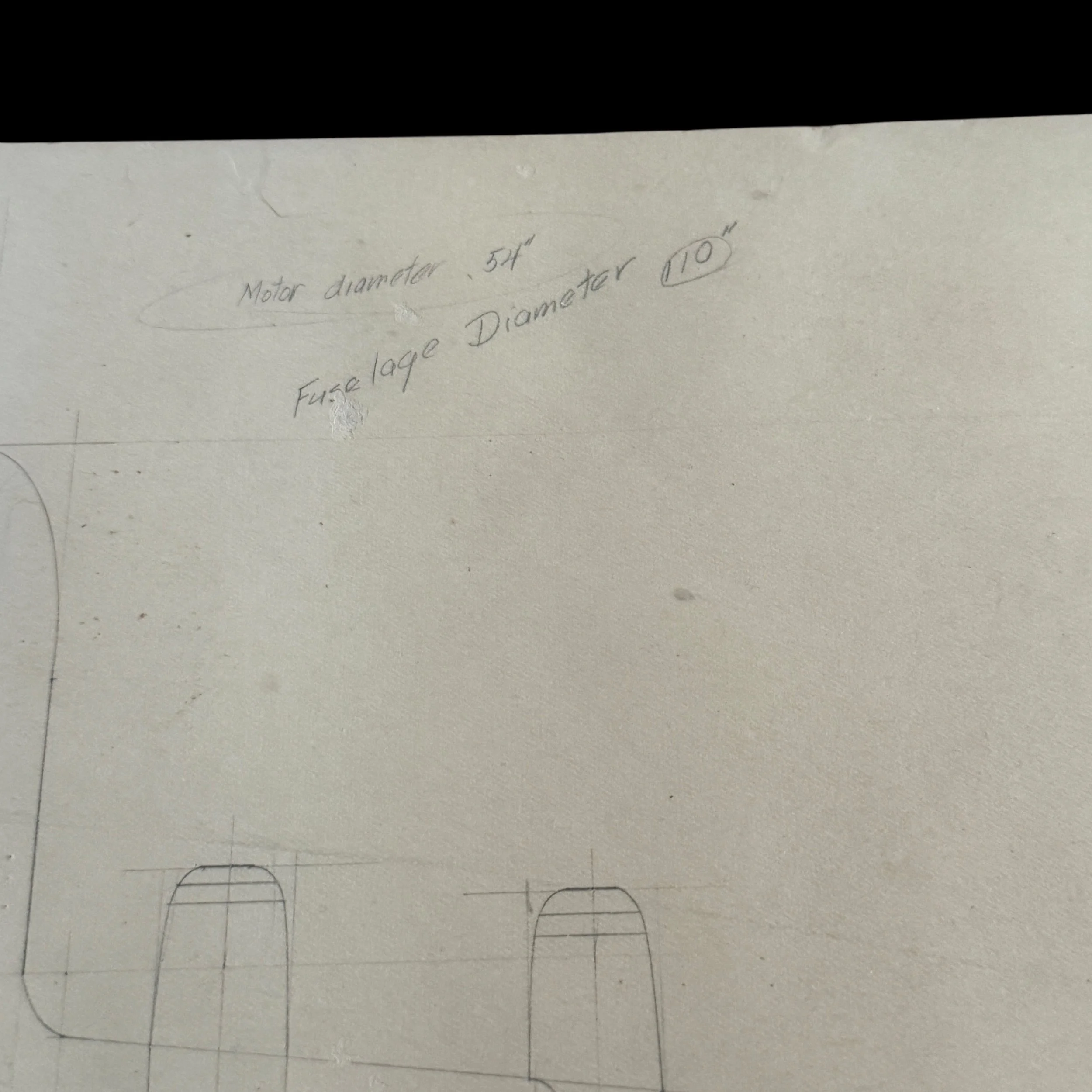

Type: EXTREMELY RARE (1 of 1) Original WWII Engineer’s Hand-Drawn DOUBLE-SIDED Boeing B-29 Superfortress Blueprint from Boeing Wichita Division "Birthplace of the Atomic Bomb Aircraft" (B-29 “Revisions” Technical Drawings)

Size: 15 × 20 inches

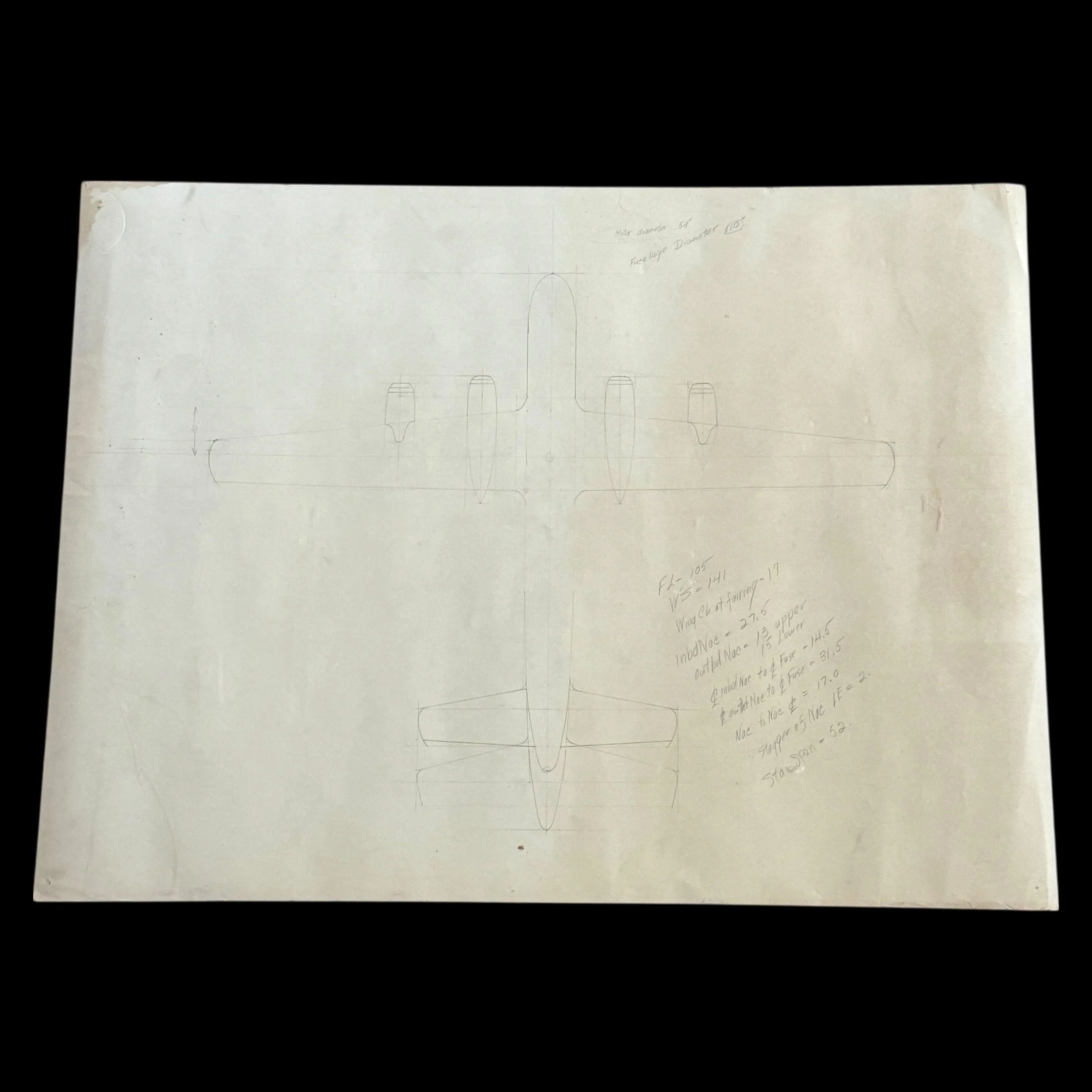

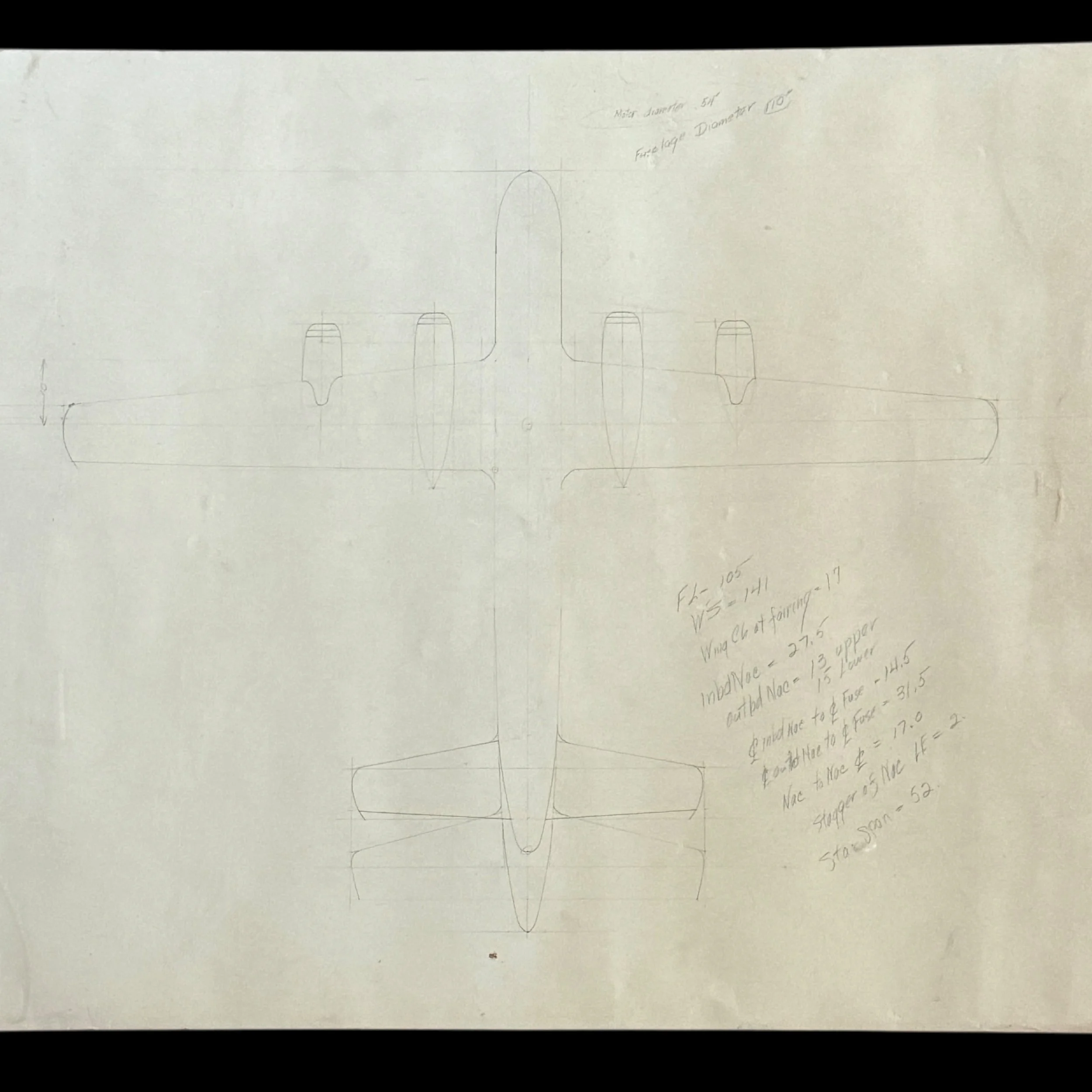

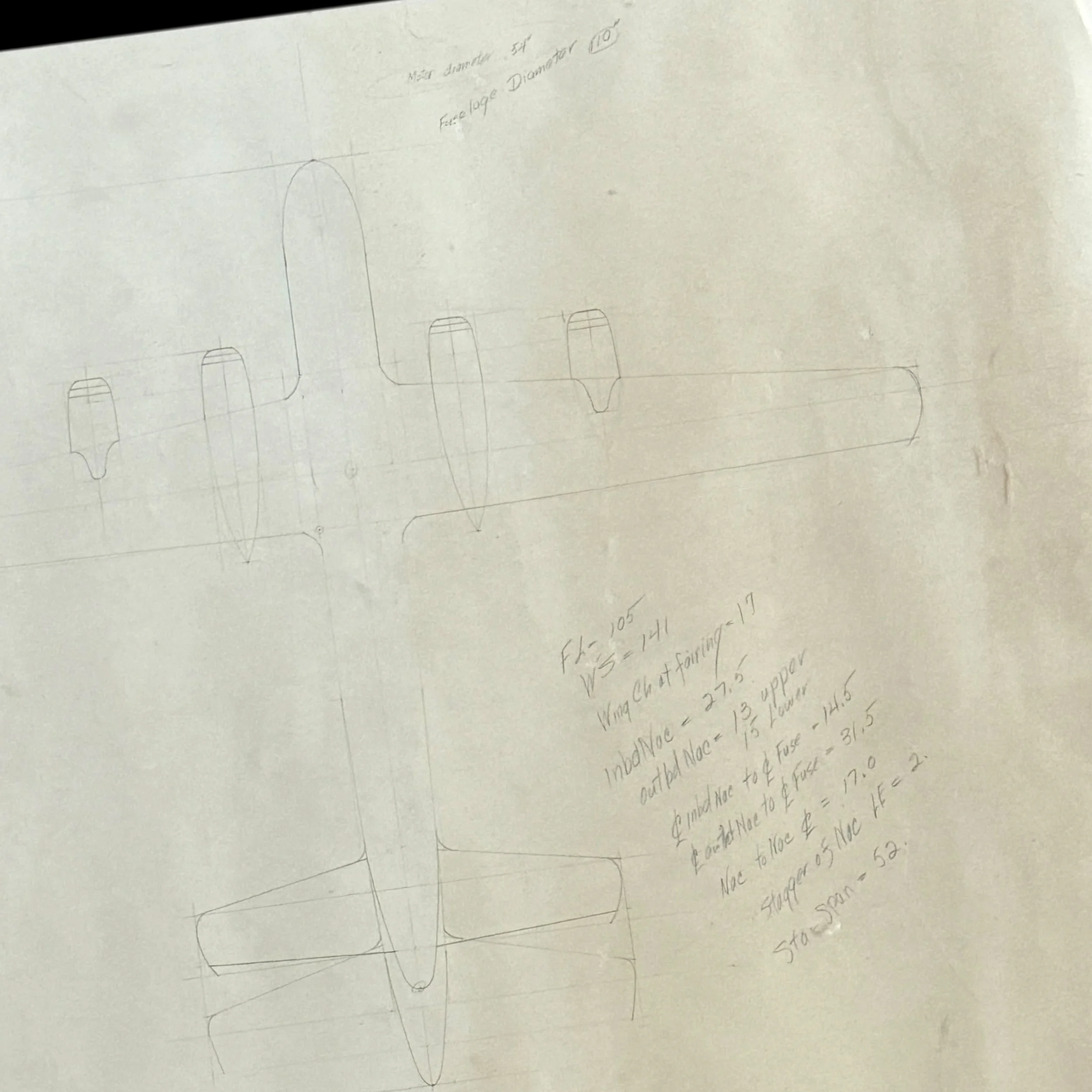

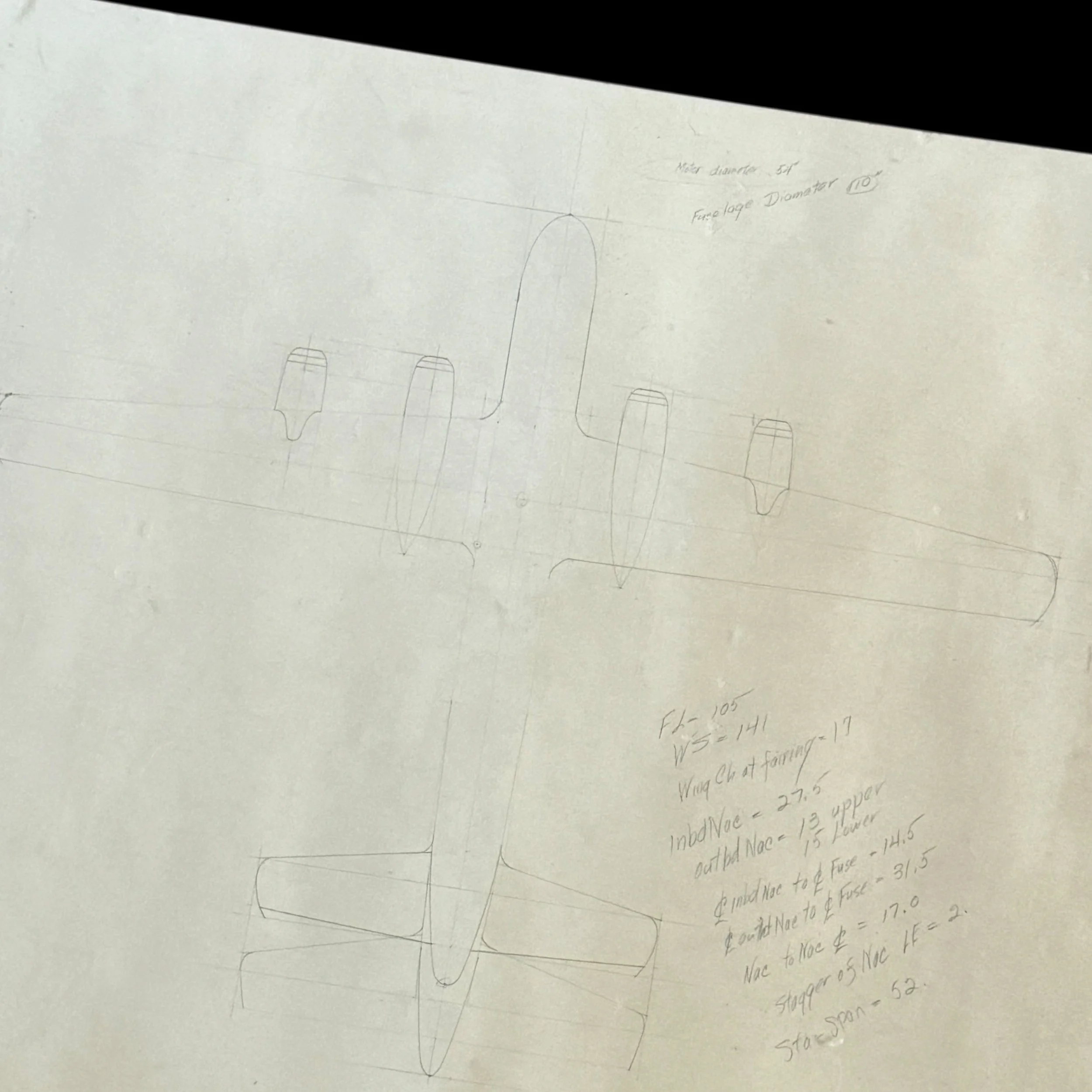

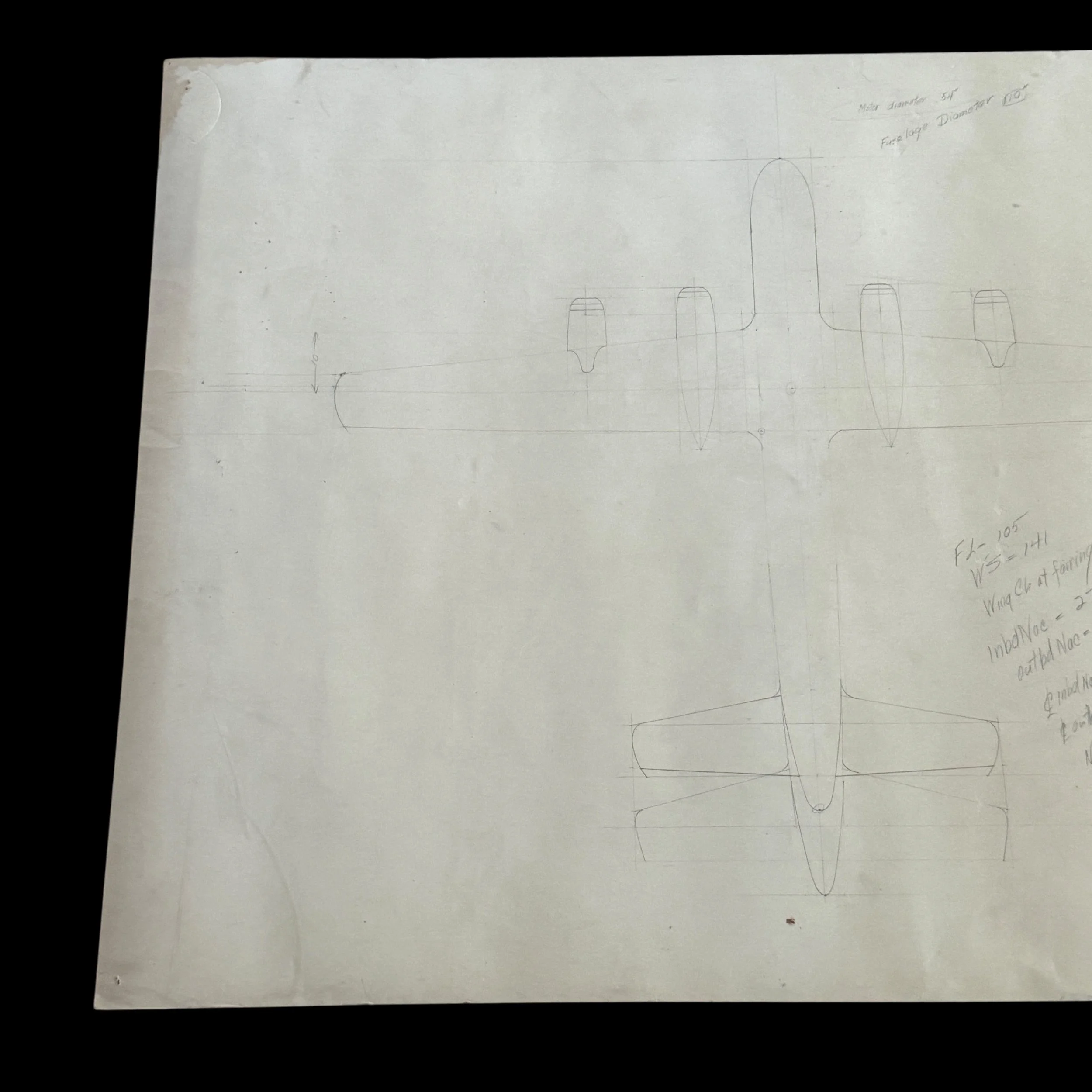

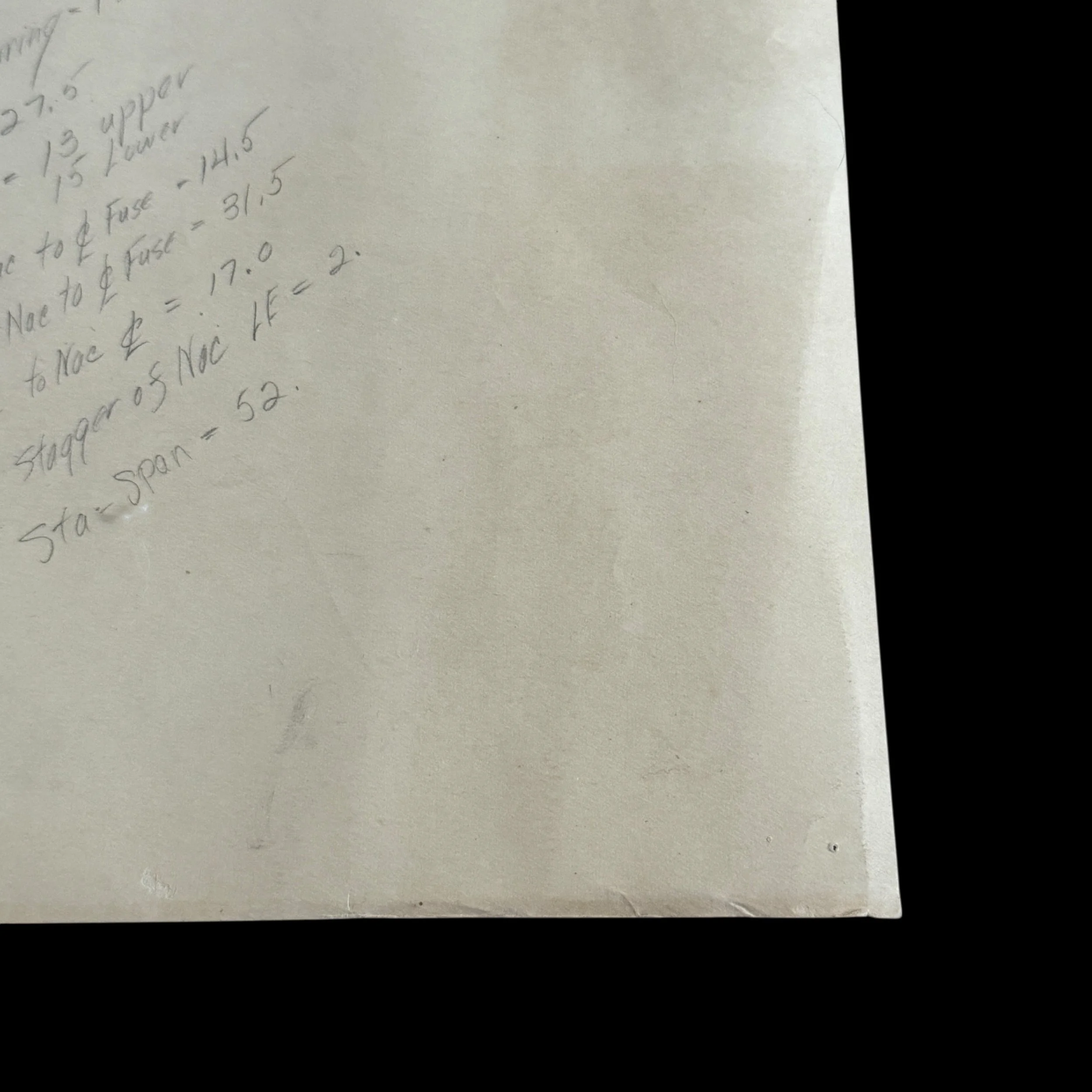

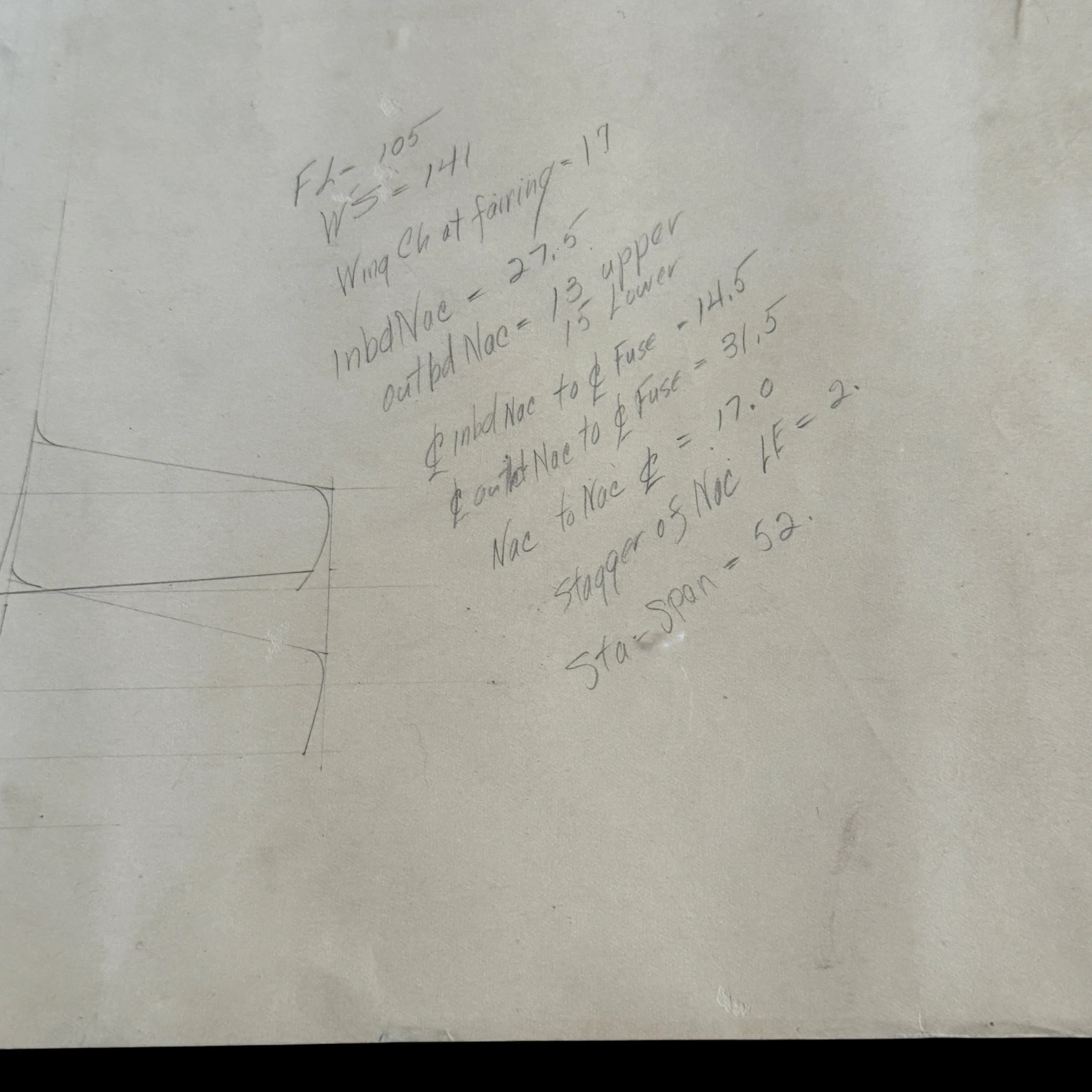

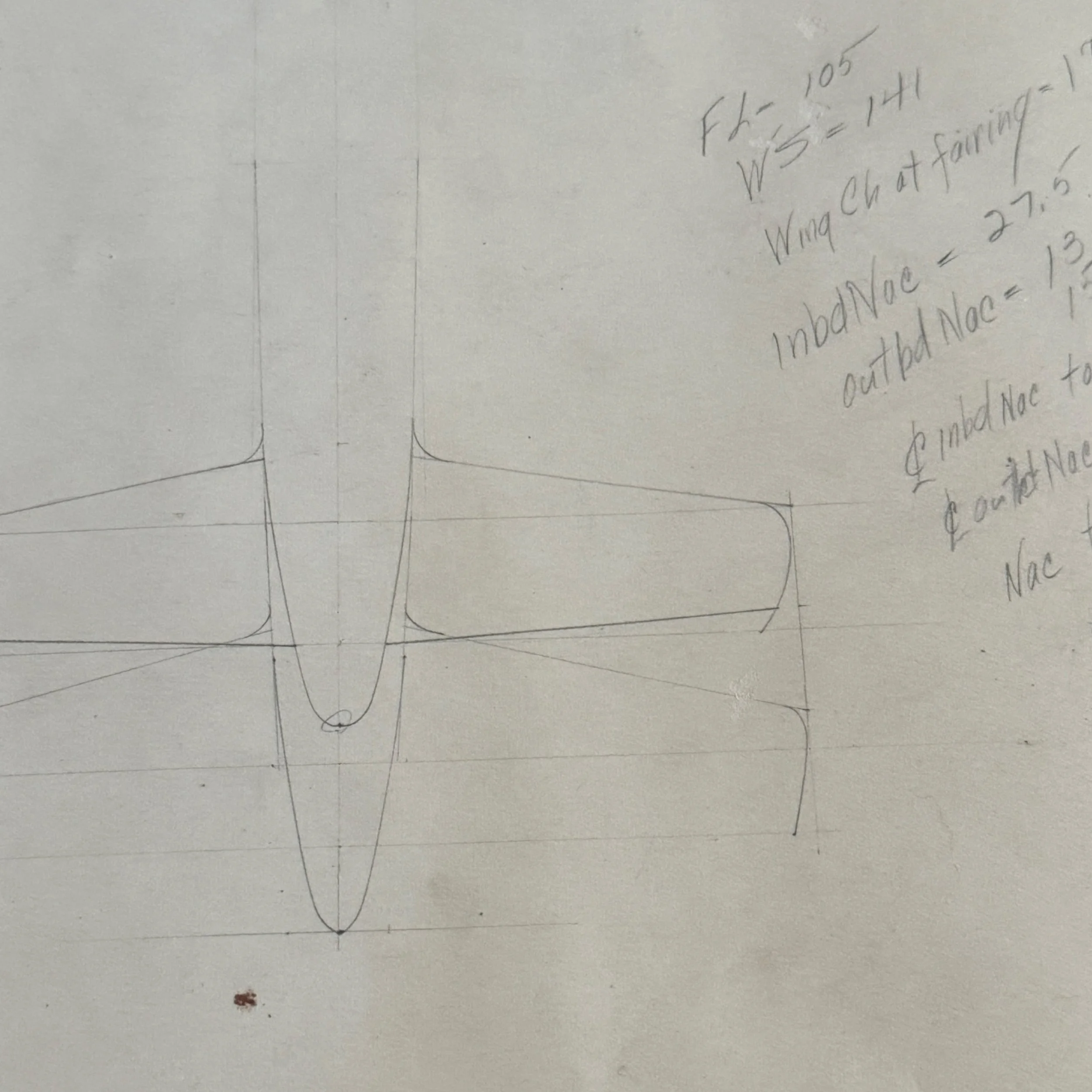

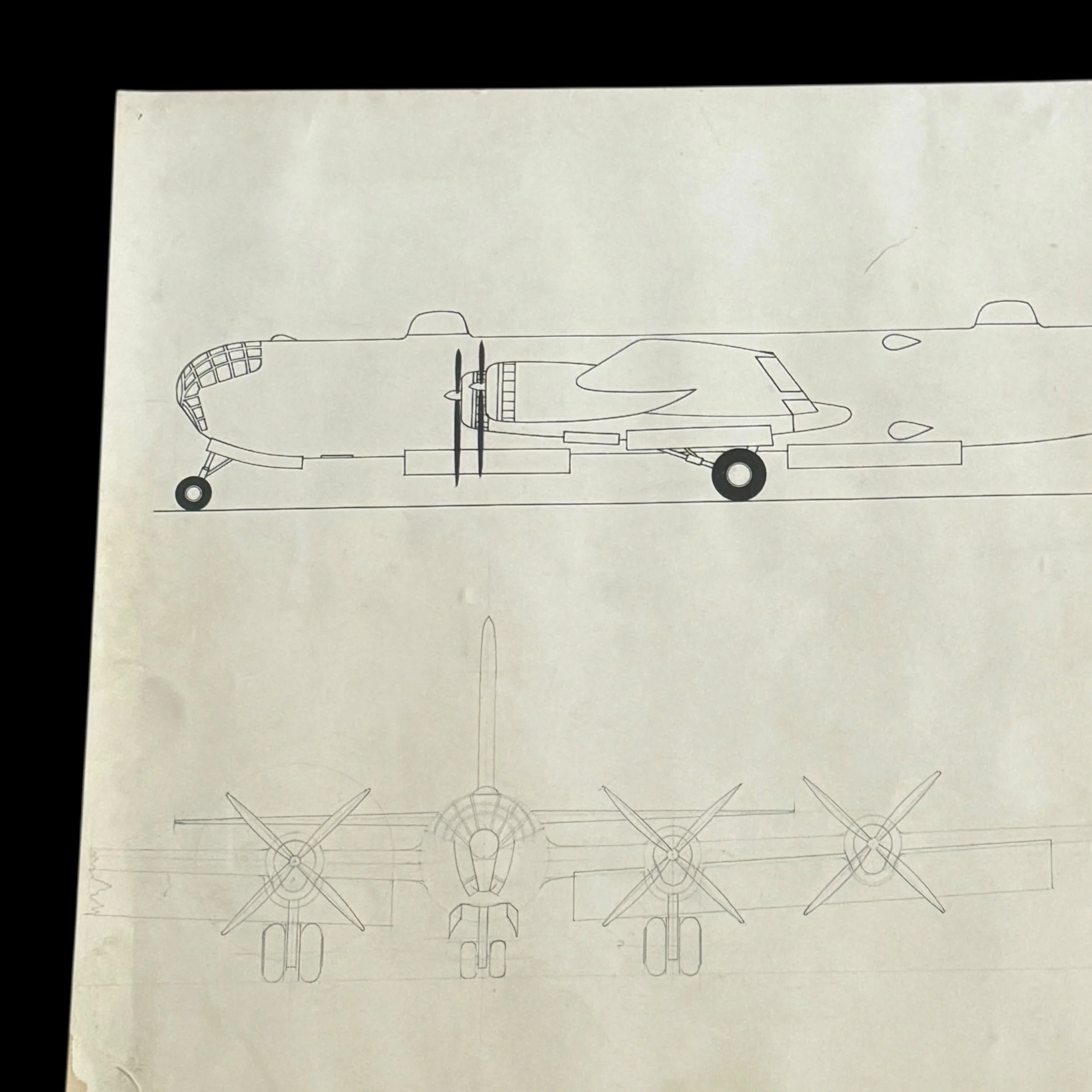

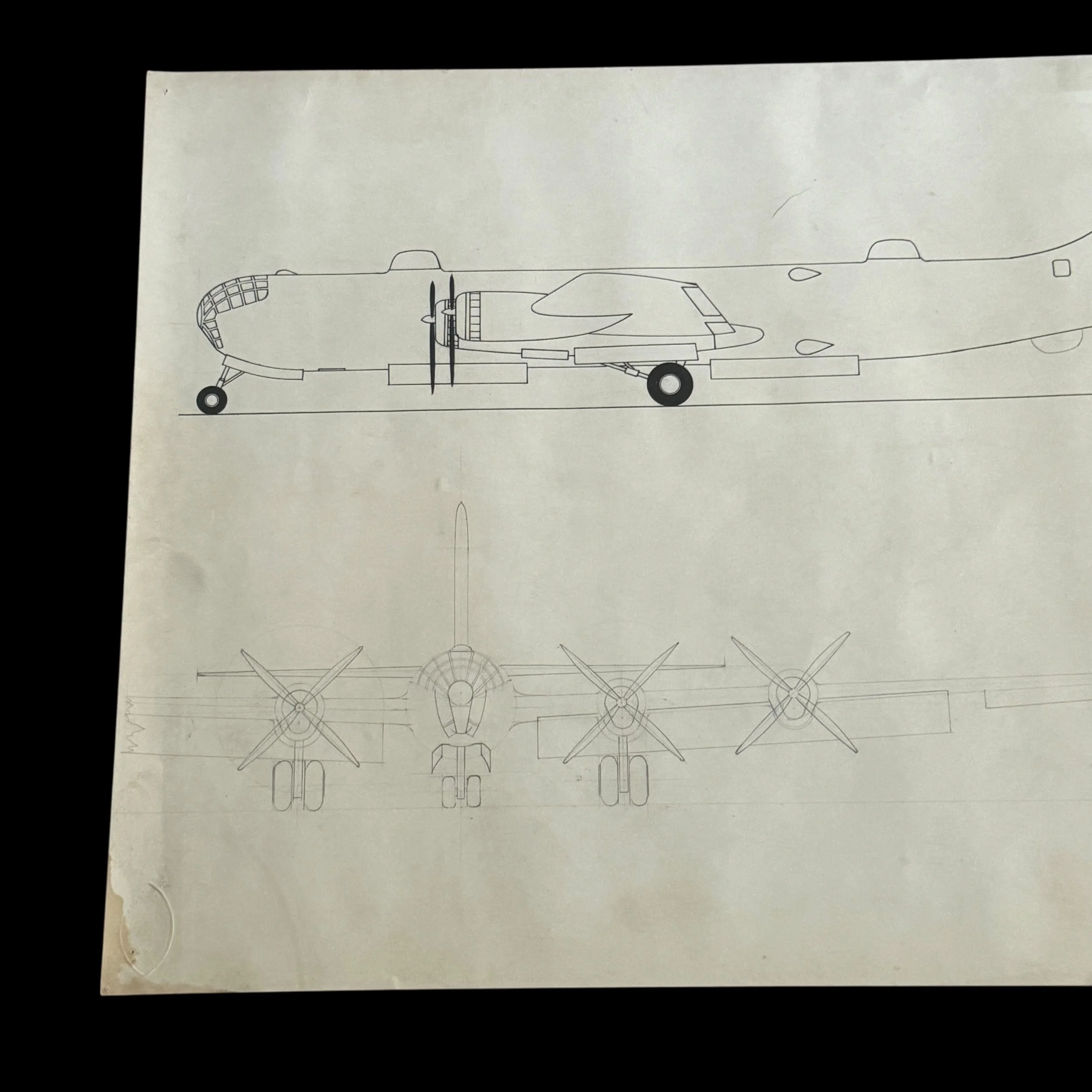

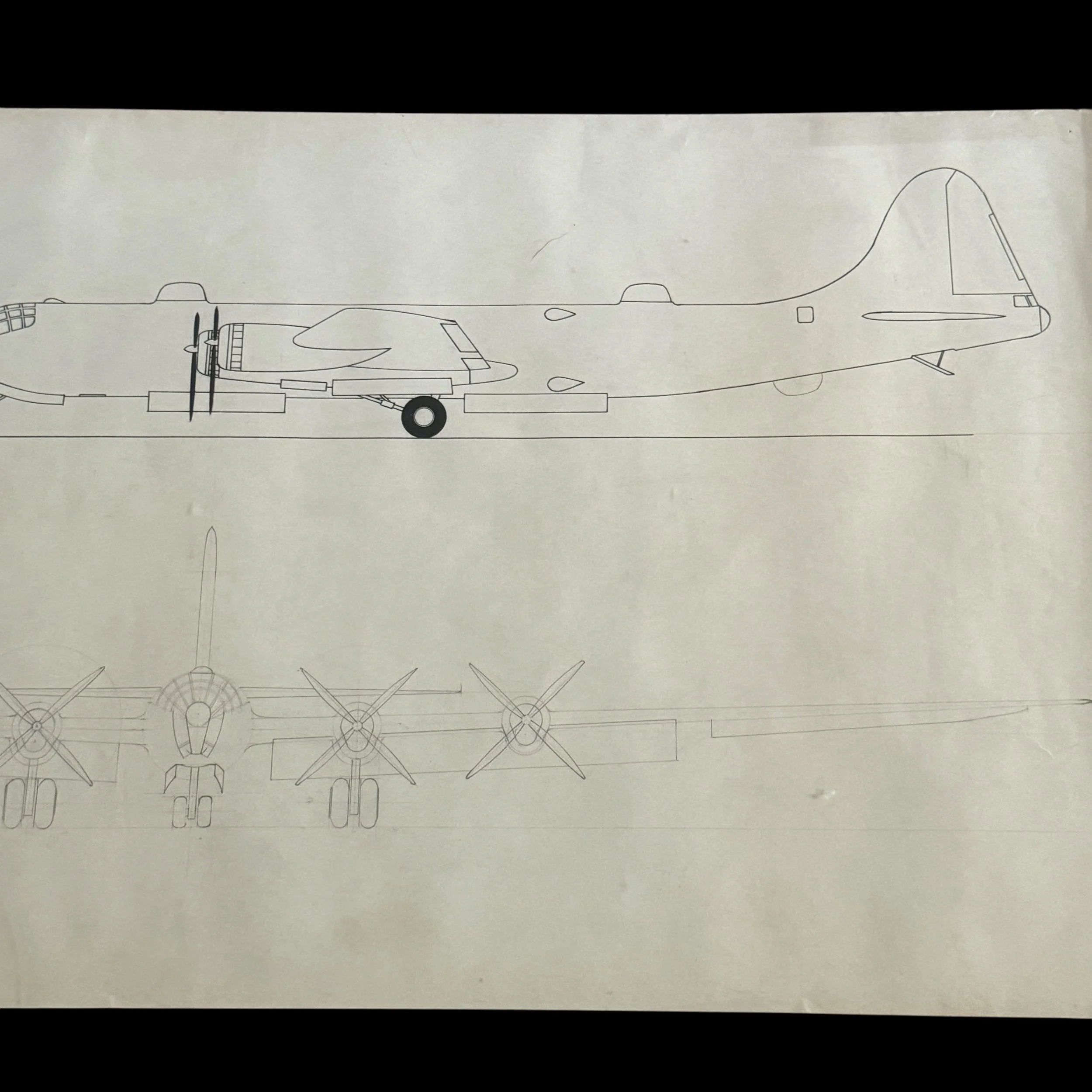

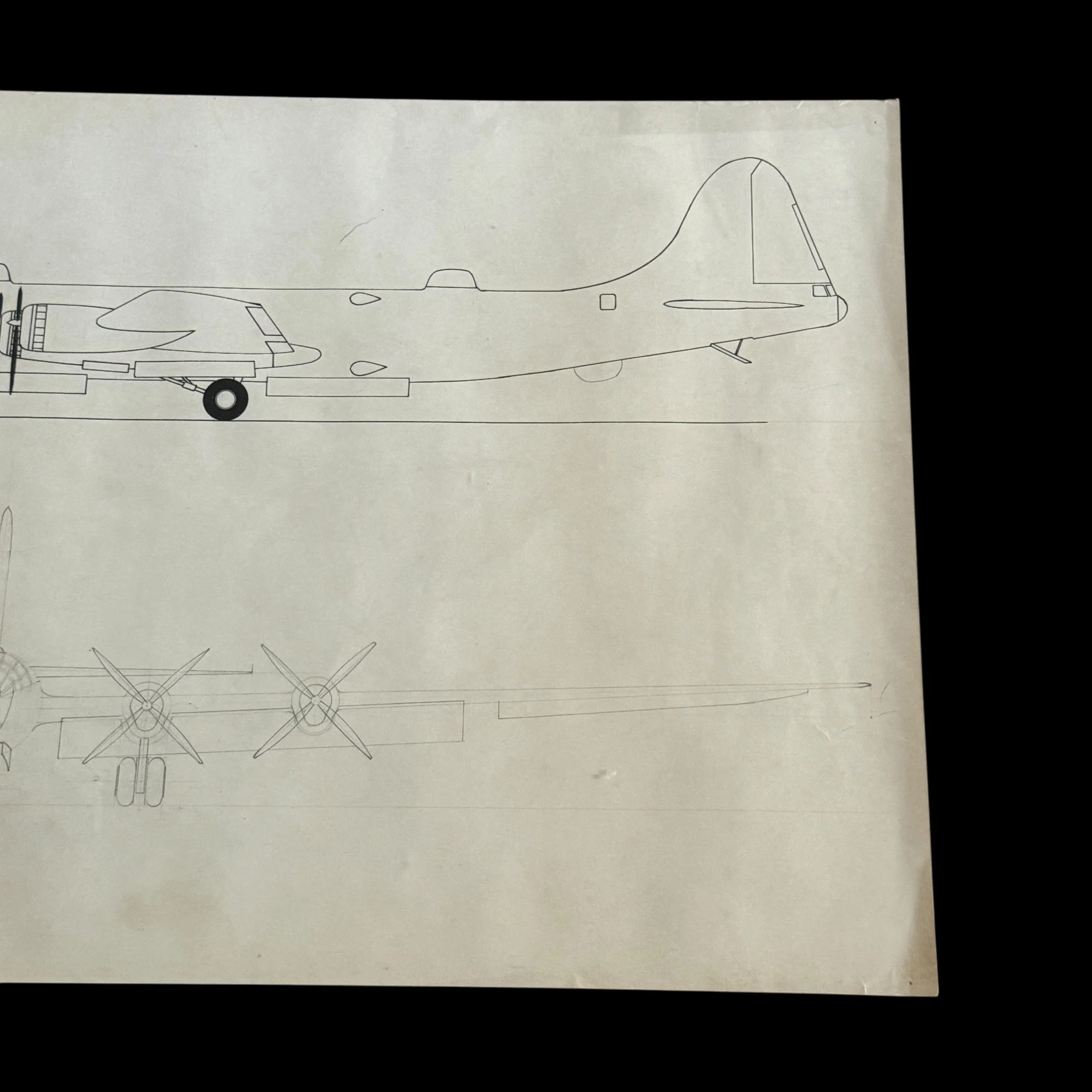

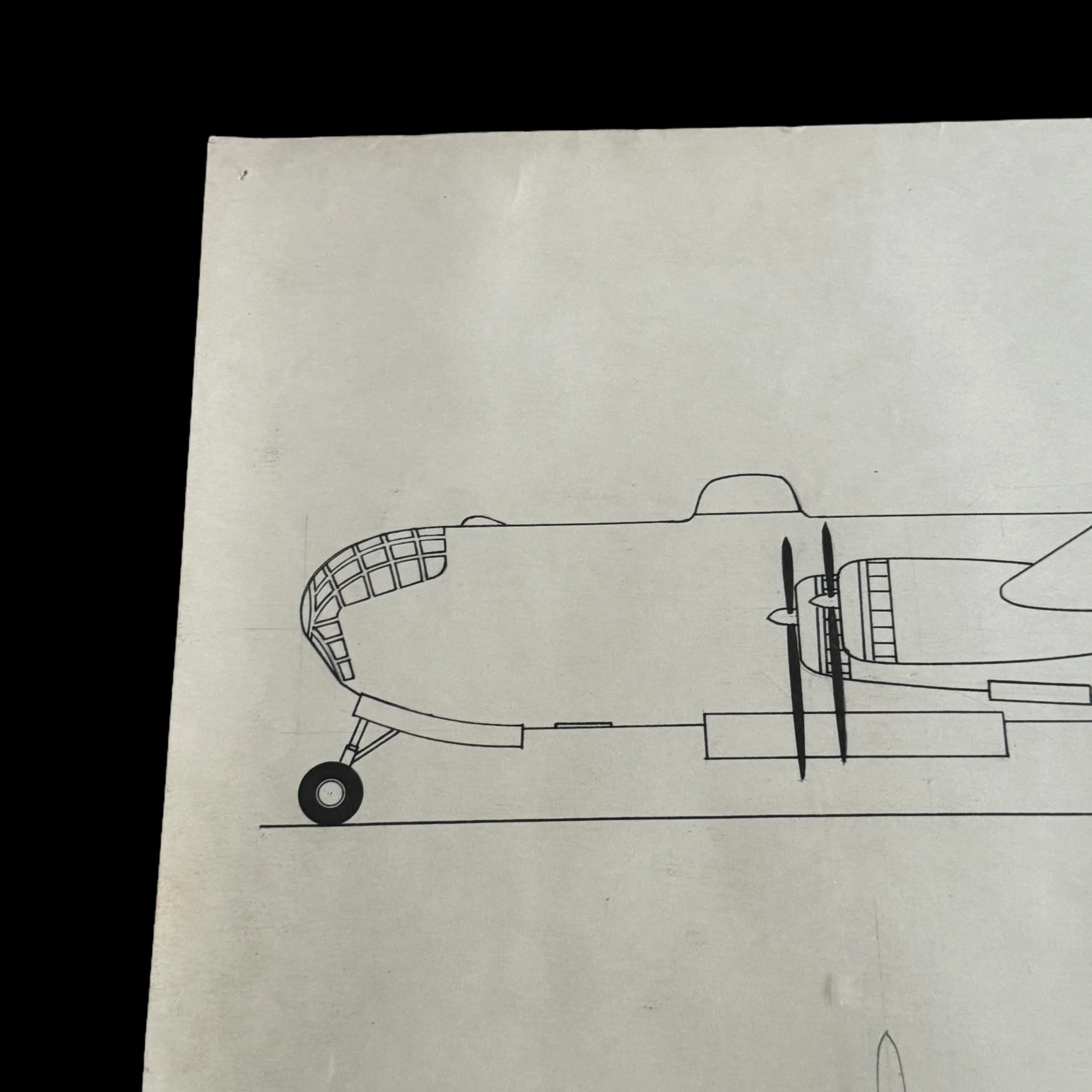

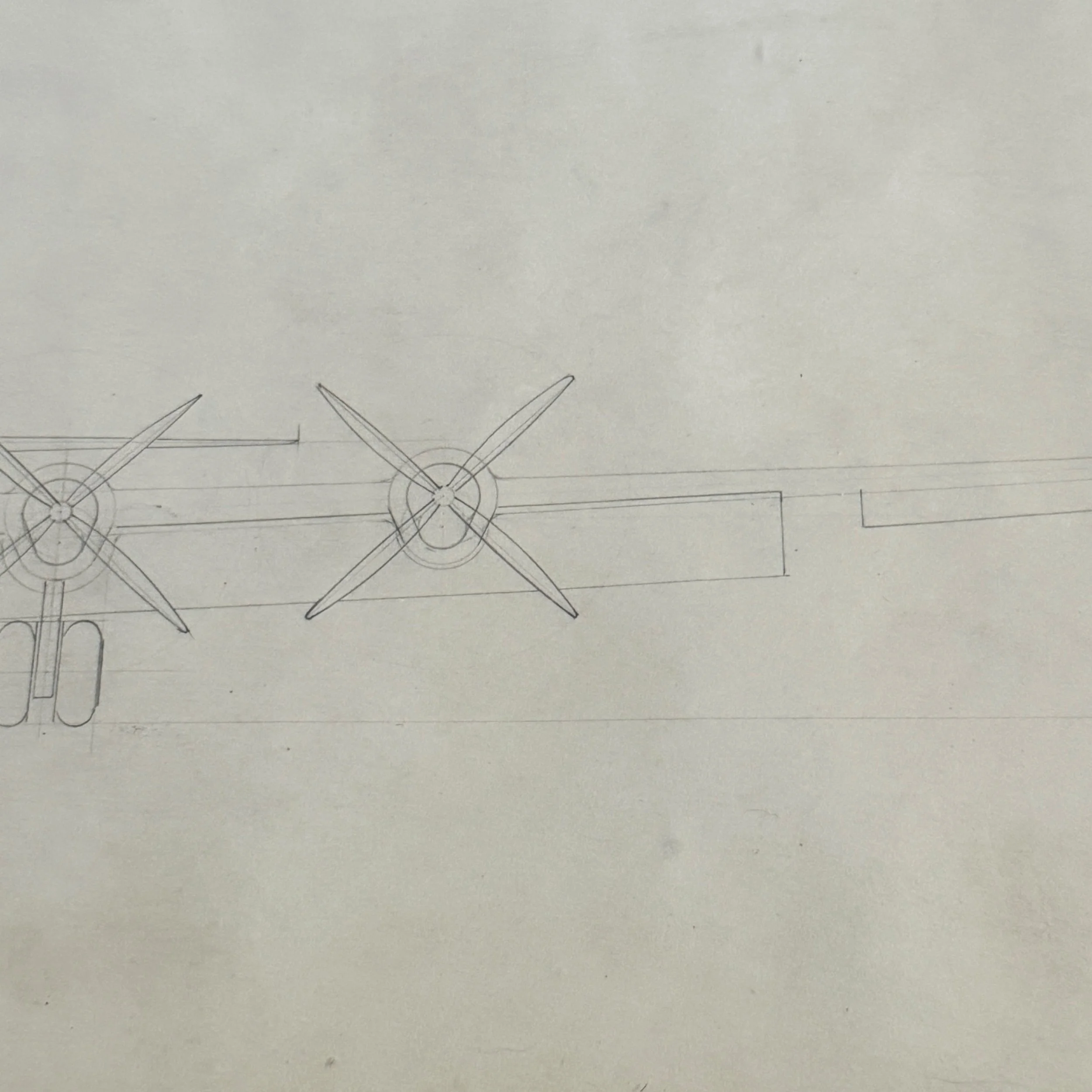

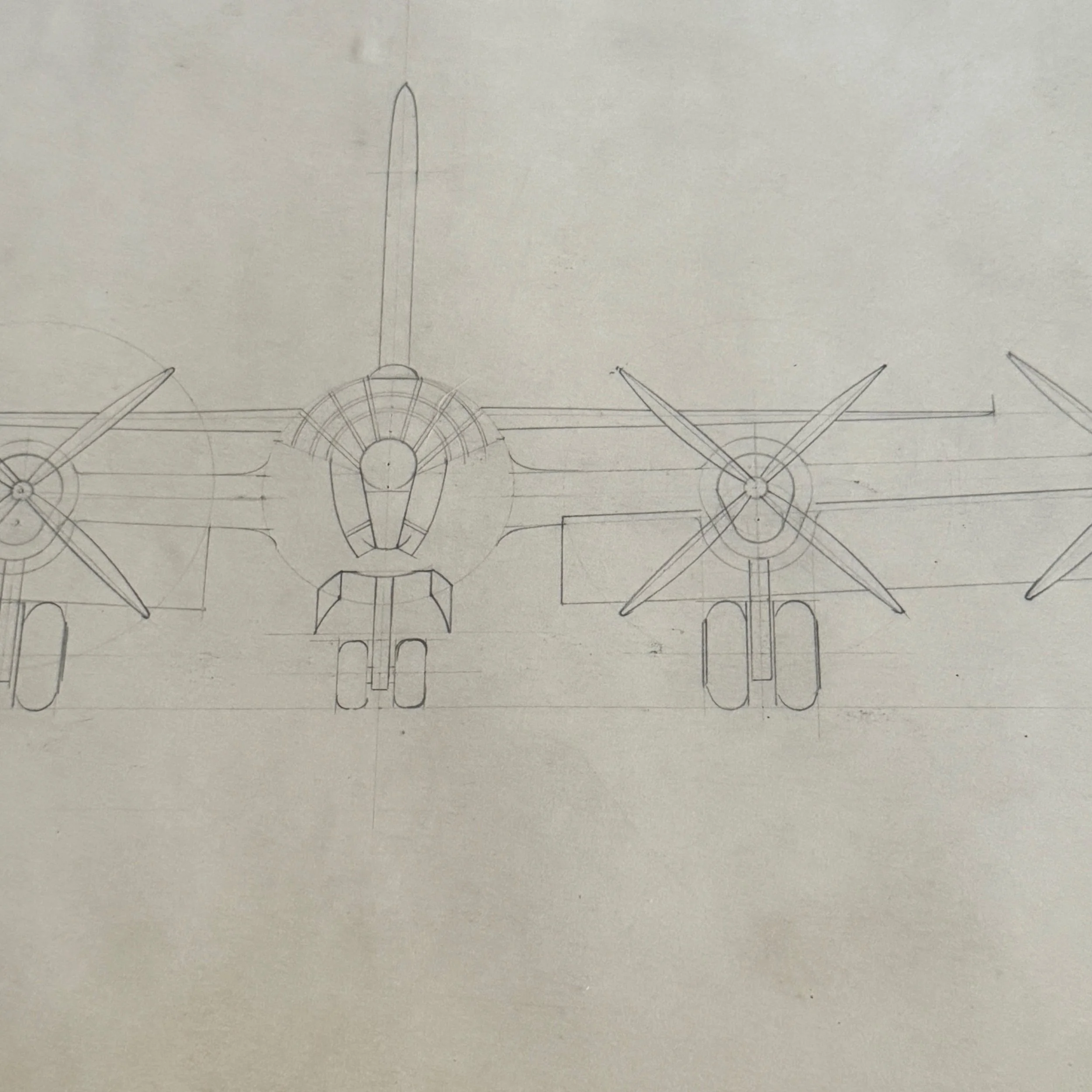

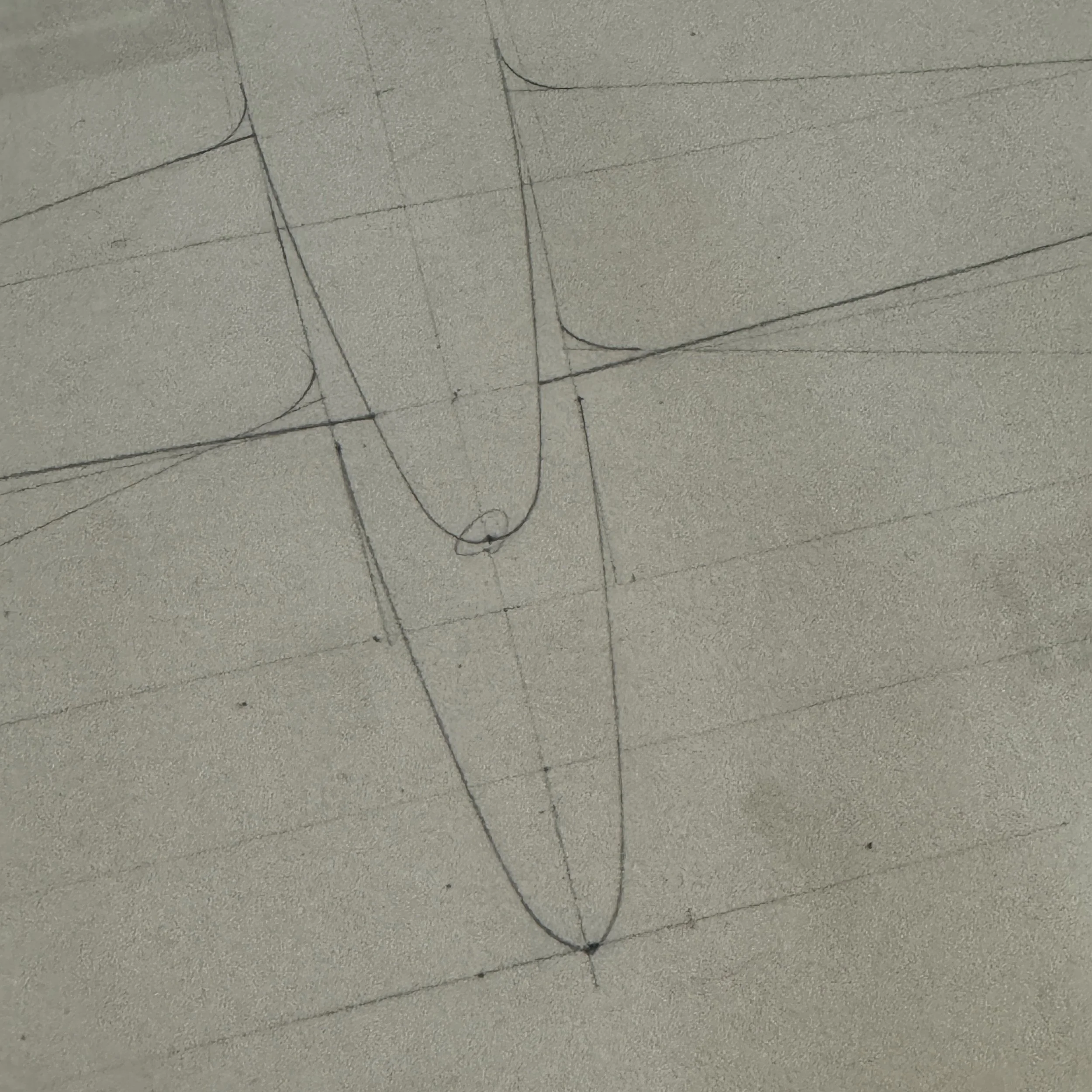

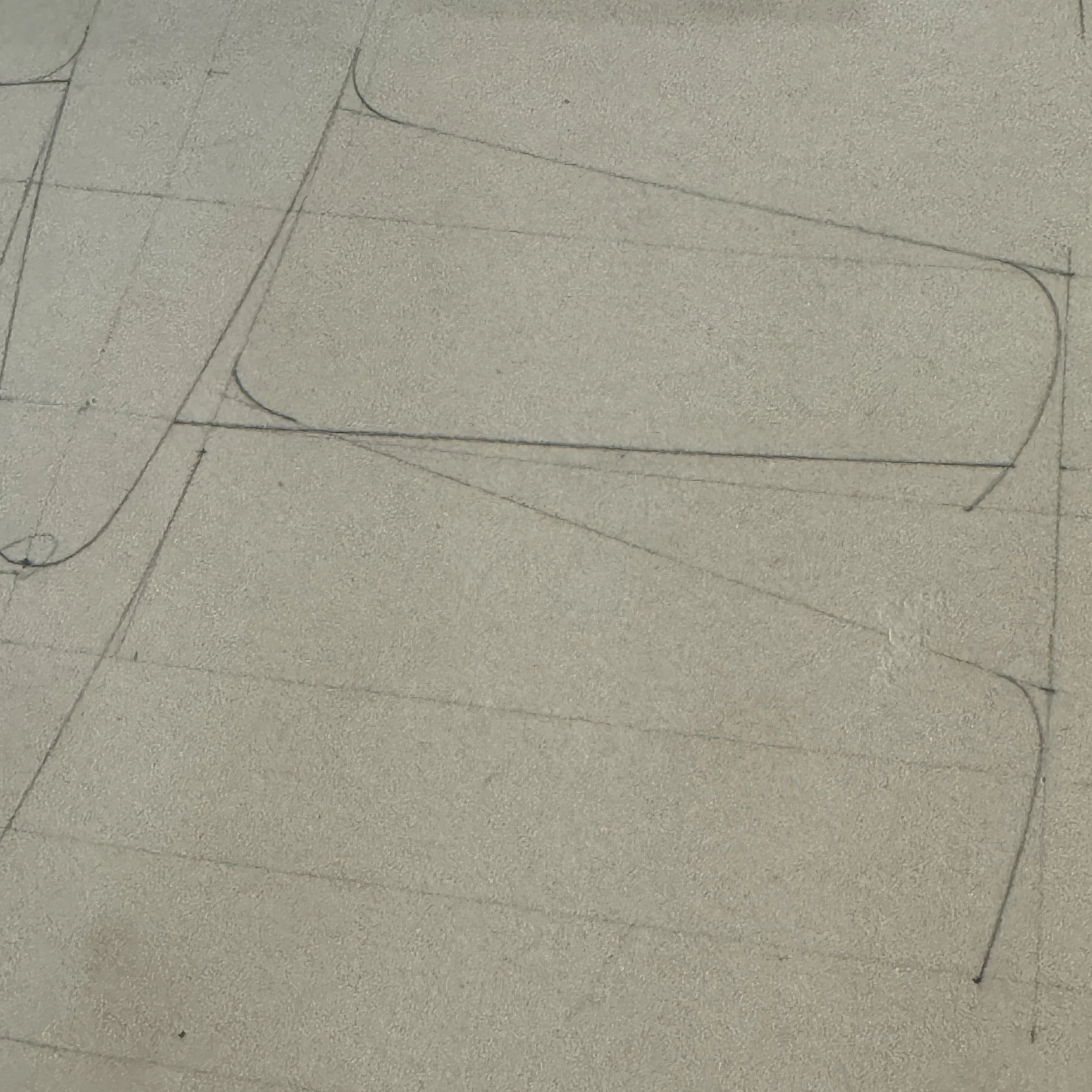

This exceptionally rare and museum-grade artifact is an original, hand-drawn blueprint schematic of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress—produced directly by the Boeing Wichita Division in Kansas, the nerve center of the most ambitious bomber program of World War II. More than just a technical document, this schematic embodies the groundbreaking engineering and relentless innovation that defined America’s strategic airpower in the final years of the war. Drawn at a time when the design of the B-29 was still considered top secret, this blueprint would have been produced under strict security protocols, accessible only to a select group of senior engineers and draftsmen working under immense wartime pressure.

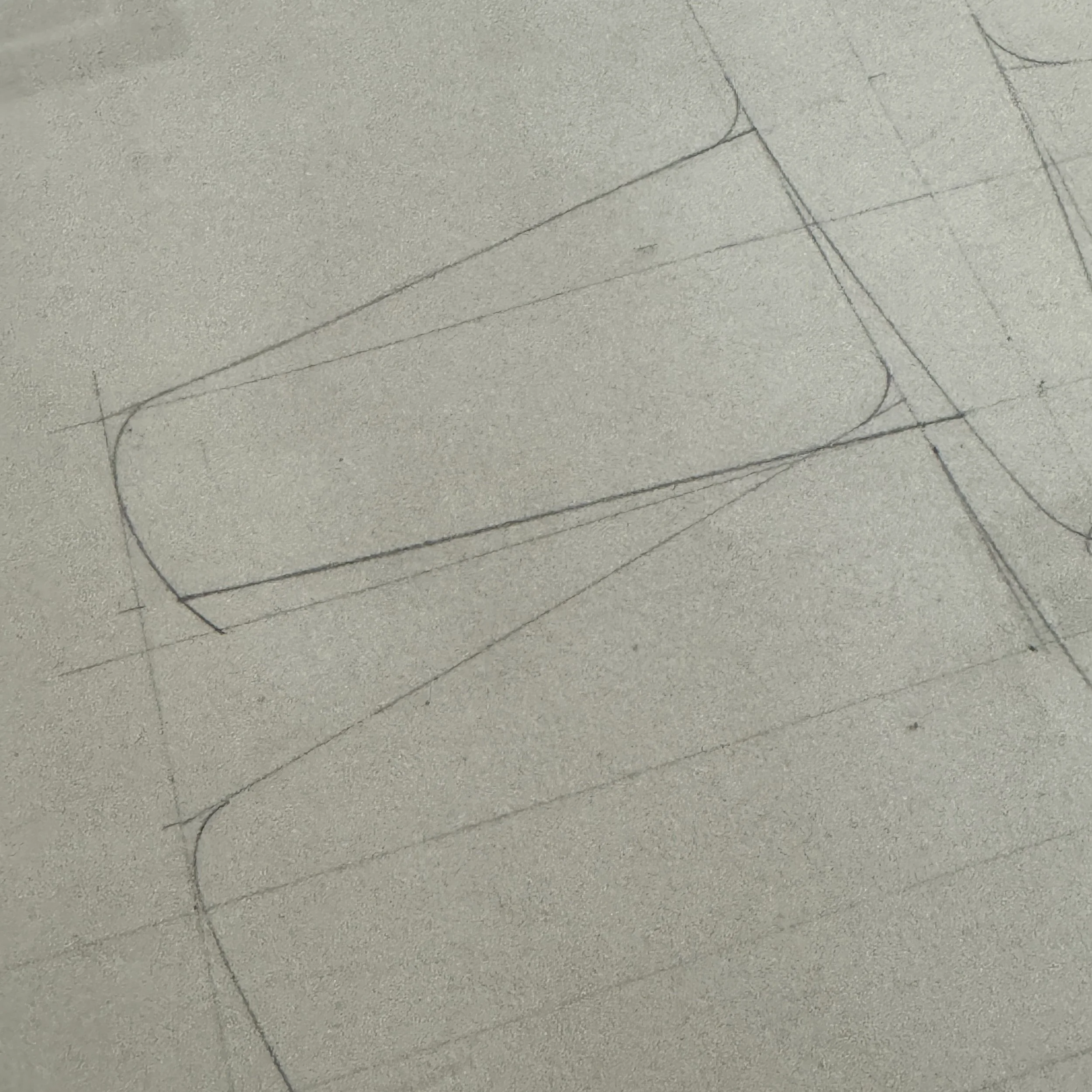

Unlike previous bombers, the B-29 was not a derivative—it was a complete redesign from the ground up. It was engineered to cruise above 30,000 feet, carry a 20,000-pound payload over thousands of miles, and operate with unprecedented speed and survivability. At the heart of this revolution was Boeing Wichita, where entire buildings were transformed into design centers filled with hand-drafting tables and teams of engineers. These blueprints—drawn with pencil and ink, annotated with precise measurements and cutaway views—were the foundational tools that guided the assembly of an aircraft composed of over one million parts and 200 miles of wiring. They were living documents, continuously updated as new systems were developed or refined on the factory floor.

What makes this particular schematic even more extraordinary is its inclusion of a full aircraft overlay showing a comparative silhouette of another well-known World War II aircraft beneath the massive form of the B-29. This scaled comparison—likely created to highlight the unprecedented size and scope of the Superfortress—underscores just how radically advanced the B-29 was in relation to its predecessors. Such overlays were rare and typically used for high-level presentations to military officials or internal engineering reviews, making this a unique glimpse into the way Boeing conveyed the scale and significance of their aircraft to decision-makers during the war.

As the war progressed, Wichita’s engineers were tasked not only with producing thousands of B-29s but also with modifying them in real time. The most famous of these modifications came under the top-secret “Silverplate” program, in which select B-29s were extensively re-engineered to carry atomic weapons. Wichita’s schematics were redrawn to accommodate the uranium-based Little Boy and plutonium Fat Man bombs, requiring changes to bomb bay configurations, release mechanisms, and even aerodynamic profiles—all decisions that originated with meticulous design work like what is preserved in this very artifact.

By the war’s end, Boeing Wichita had produced more B-29s than any other facility, including the Enola Gay, which dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima. But beyond the aircraft themselves, it was the engineering—the blueprints, the calculations, the human minds behind the drafting pencils—that made the B-29 program a success. This schematic is not just a historical document; it is a tangible piece of the process that brought one of the most important aircraft in history into existence. It captures a moment when American innovation, wartime necessity, and industrial might converged—blueprint by blueprint, rivet by rivet—in the heart of Kansas.

Forged for Victory: The B-29 Superfortress, the Atomic Bomb, and the Boeing Wichita, Kansas Division that Built History:

The B-29 Superfortress was not only the most advanced bomber of World War II—it was the aircraft that delivered the most consequential weapons in human history. Developed under immense pressure by Boeing, the B-29 pushed the boundaries of what a bomber could do, culminating in the atomic missions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At the center of this monumental engineering feat was the Boeing Wichita Division in Kansas, the primary production site for the B-29 and home to the aircraft that would ultimately alter the course of the war—and the world.

The need for a long-range, high-altitude, heavy bomber was urgent. The Pacific Theater presented vast distances, making traditional bombers like the B-17 inadequate for sustained operations against the Japanese mainland. The B-29 was the answer: an enormous, pressurized bomber capable of carrying nearly 10 tons of bombs over 3,000 miles. But more than its sheer size or range, it was the platform’s adaptability that made it critical to the Manhattan Project. It was the only aircraft with the speed, altitude, and payload capacity necessary to deliver an atomic bomb.

By early 1943, Boeing’s Wichita plant was at full throttle. Wichita workers—many of them new to aviation—were trained rapidly and thrust into a program unlike any before. The scale of the B-29’s complexity meant that even seasoned engineers were in unfamiliar territory. J.E. Schaefer, Boeing Wichita’s leader and a former West Point classmate of General Eisenhower, described the task with a sense of sober gravity. In letters to both his workers and to Eisenhower himself, Schaefer emphasized that this was a mission for which “no one had experience,” and that success depended on humility, focus, and unity—comparing his factory crew to soldiers on the front lines. “We must be humble and we must work to make good,” he wrote, warning against complacency. The war would be won only through collective effort—“you in the plant, me at my desk, the soldier at the front and the sailor at sea.”

The urgency behind these words became even more critical when, in December 1943, the U.S. Army Air Forces initiated the “Silver Plated Project”—later shortened to “Silverplate.” This highly classified program aimed to modify B-29s specifically for the atomic mission. It began with aircraft 42-6259, flown from Smoky Hill Army Airfield to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. There, engineers stripped the bomber of unnecessary weight, reconfigured its bomb bay, and rewired its release mechanisms to accommodate the first atomic bomb prototypes. These included the 17-foot-long plutonium “Thin Man,” which ultimately proved unfeasible. Still, its failure prompted key design breakthroughs that paved the way for the successful integration of two radically different bomb designs: the uranium-based “Little Boy” and the plutonium-based “Fat Man.”

These weapons demanded precise modification. Little Boy, while shorter than Thin Man at just over 10 feet, weighed a staggering 9,700 pounds—nearly the maximum payload of a B-29. Fat Man, more compact but spherical, required an equally specialized suspension and release system. Standard B-29 bomb bays had to be reinforced, bay doors altered, and internal structure reshaped. Moreover, the Silverplate B-29s were fitted with upgraded engines and stripped-down defenses to increase performance—giving the aircraft the speed and altitude needed to escape the nuclear blast.

Wichita’s role in this process was foundational. Every aircraft used in the first bombing raid on Japan in June 1944 was built there. The most historically significant of them all—the Enola Gay—was rolled out of Boeing’s Wichita plant and later modified under the Silverplate program. On August 6, 1945, Colonel Paul Tibbets and his crew flew the Enola Gayfrom Tinian Island to Hiroshima, where they released Little Boy—the first atomic weapon ever used in warfare. Just three days later, Bockscar, another Silverplate-modified B-29, dropped Fat Man on Nagasaki. The devastating effectiveness of these missions—both launched from B-29s—ushered in the nuclear age and forced Japan’s surrender, effectively ending the war.

Yet behind these headlines was a story of thousands of Americans working long hours in the Kansas heartland—engineers, welders, riveters, and draftsmen—each contributing to a bomber that had no precedent. Many were women, many had never before worked in manufacturing, and nearly all understood the gravity of the aircraft they were building. Schaefer, deeply aware of the stakes, kept morale high through personal letters, wartime speeches, and direct appeals to patriotism and discipline.

The B-29 Superfortress remains, to this day, a singular engineering achievement—a fusion of innovative design, industrial scale, and strategic vision. But it also remains a symbol of the atomic era. Without the B-29, there would have been no effective delivery system for the world’s first nuclear weapons. The aircraft’s pressurized cabin, advanced bomb sights, and long-range capabilities made it the only viable choice. And its legacy was forged not just in the skies over Japan, but in the drafting rooms, machine shops, and assembly lines of Wichita, Kansas.