RARE! WWII August 1945 Type 1 U.S. Army Air Force Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Damage Assessment Aftermath Photograph

RARE! WWII August 1945 Type 1 U.S. Army Air Force Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Damage Assessment Aftermath Photograph

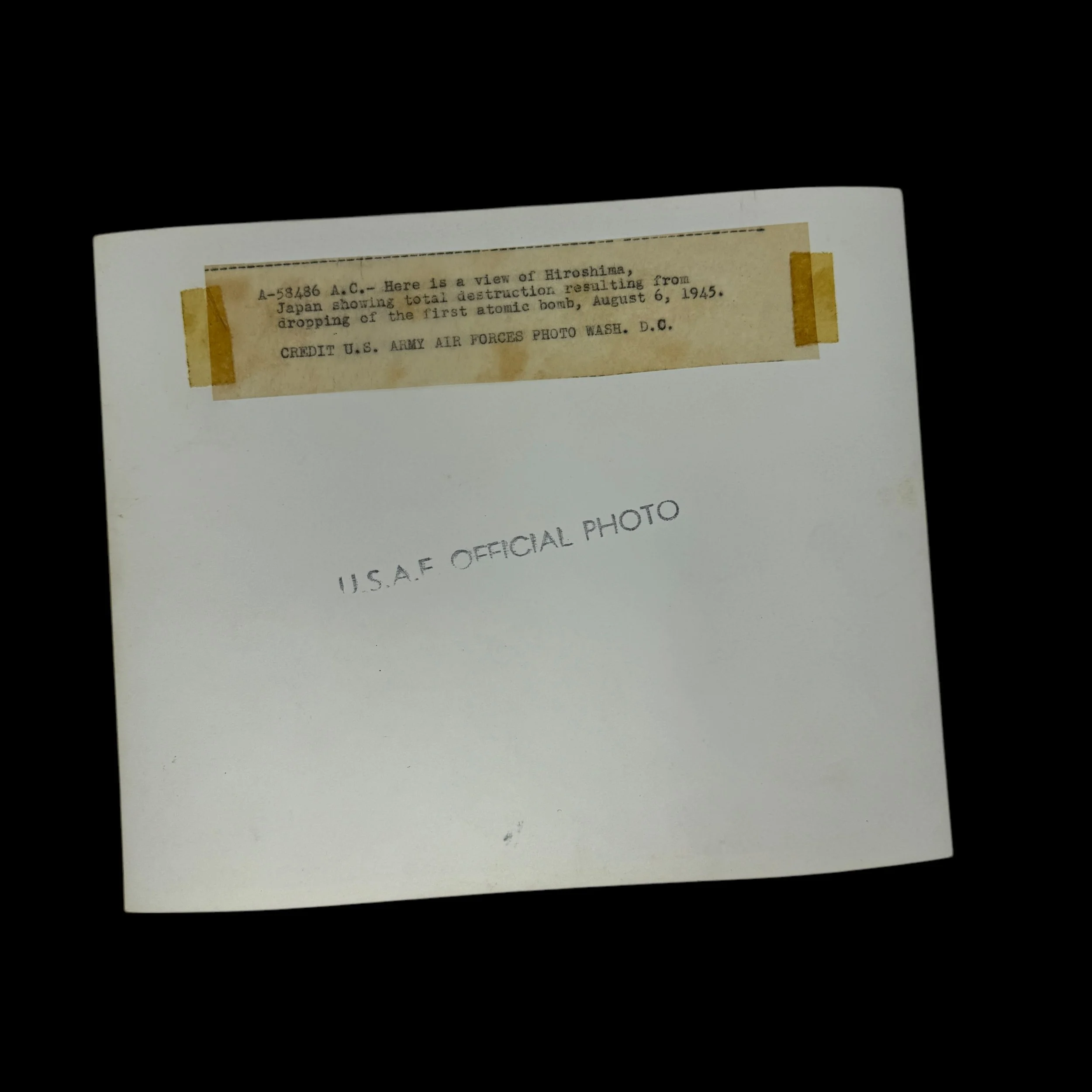

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

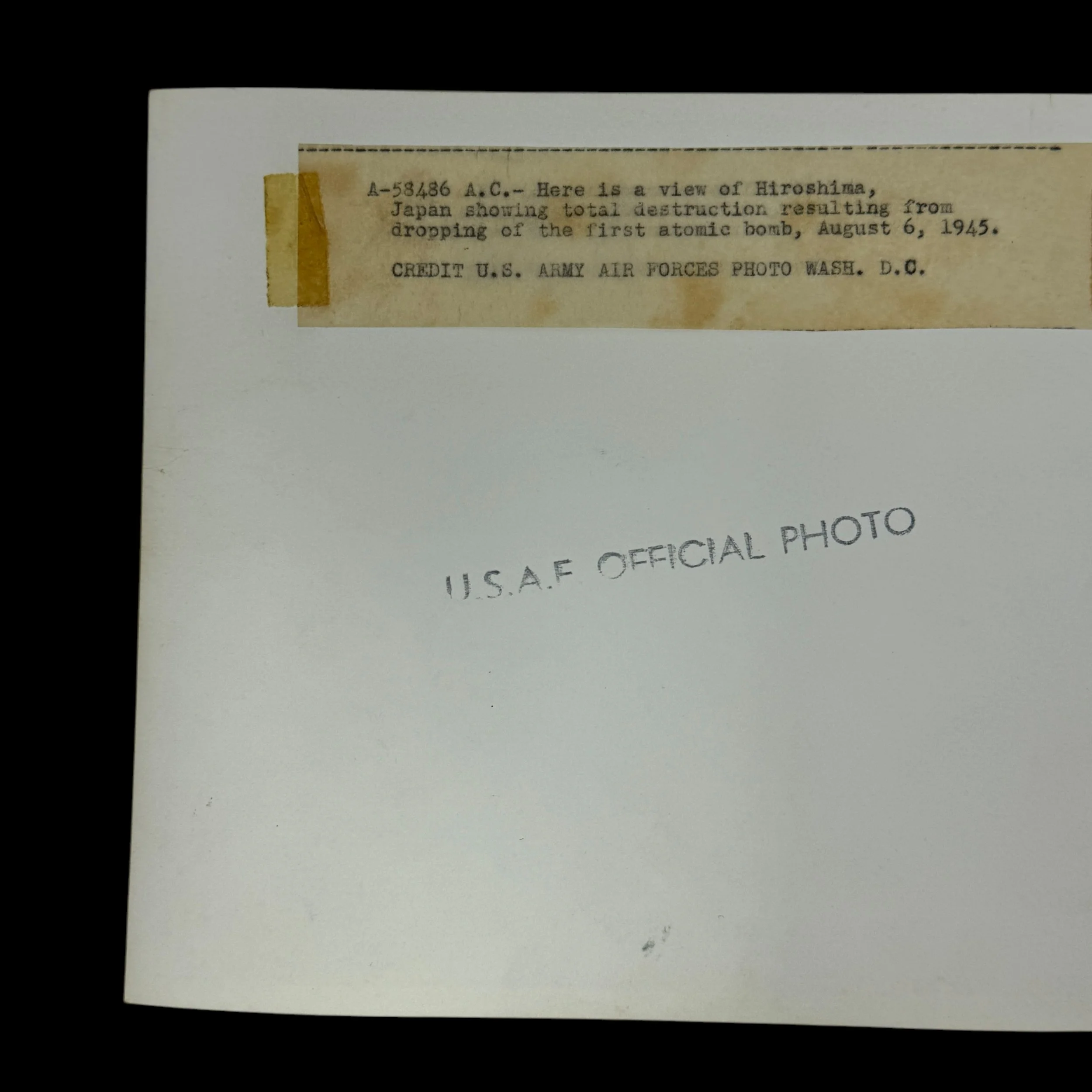

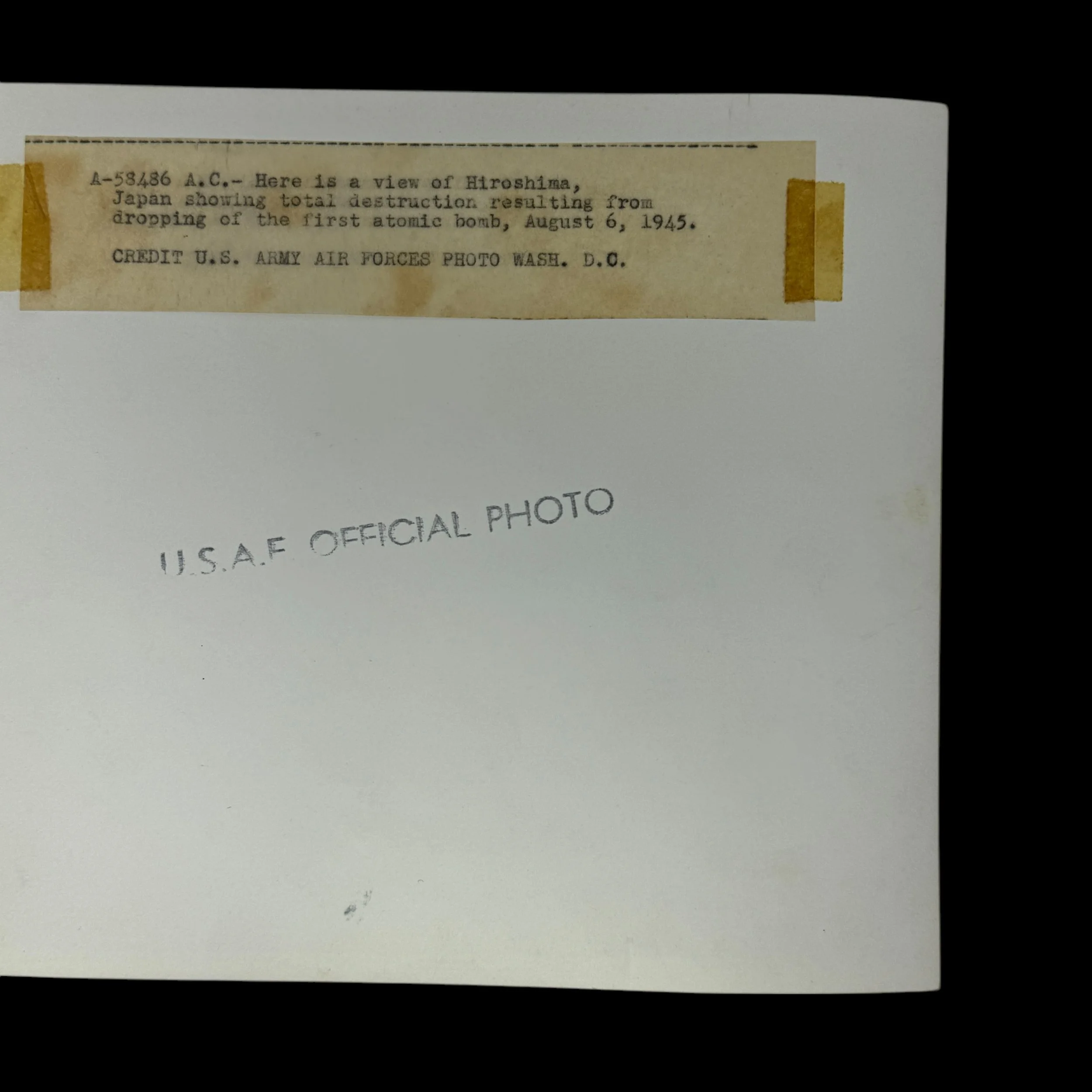

Size: 7 and 1/2 × 9 and 1/8 inches

Type: First Edition - Type 1 Photograph

Subject: Hiroshima Atomic Bomb - U.S.A.F. Damage Assessment Aftermath

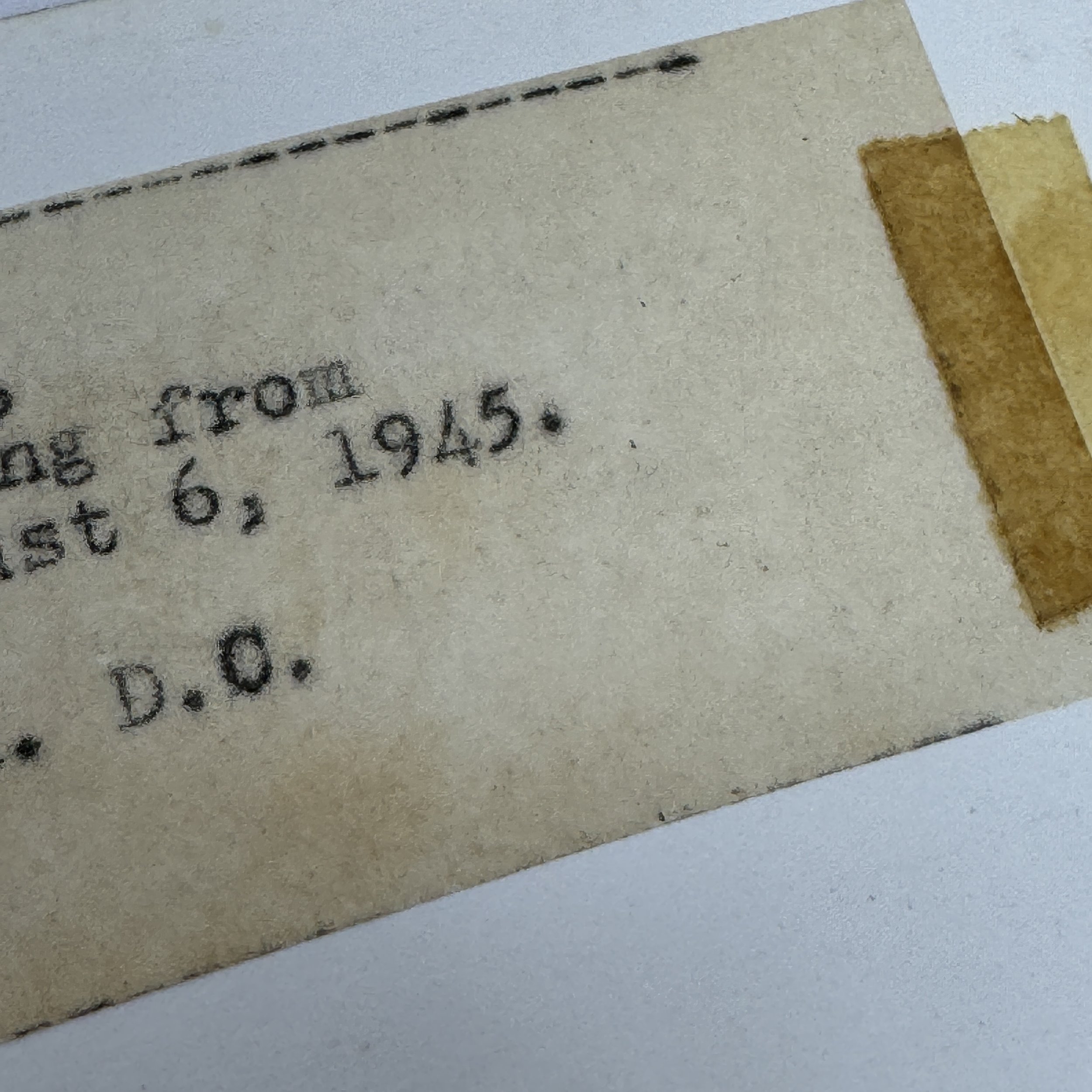

Dated: August 1945

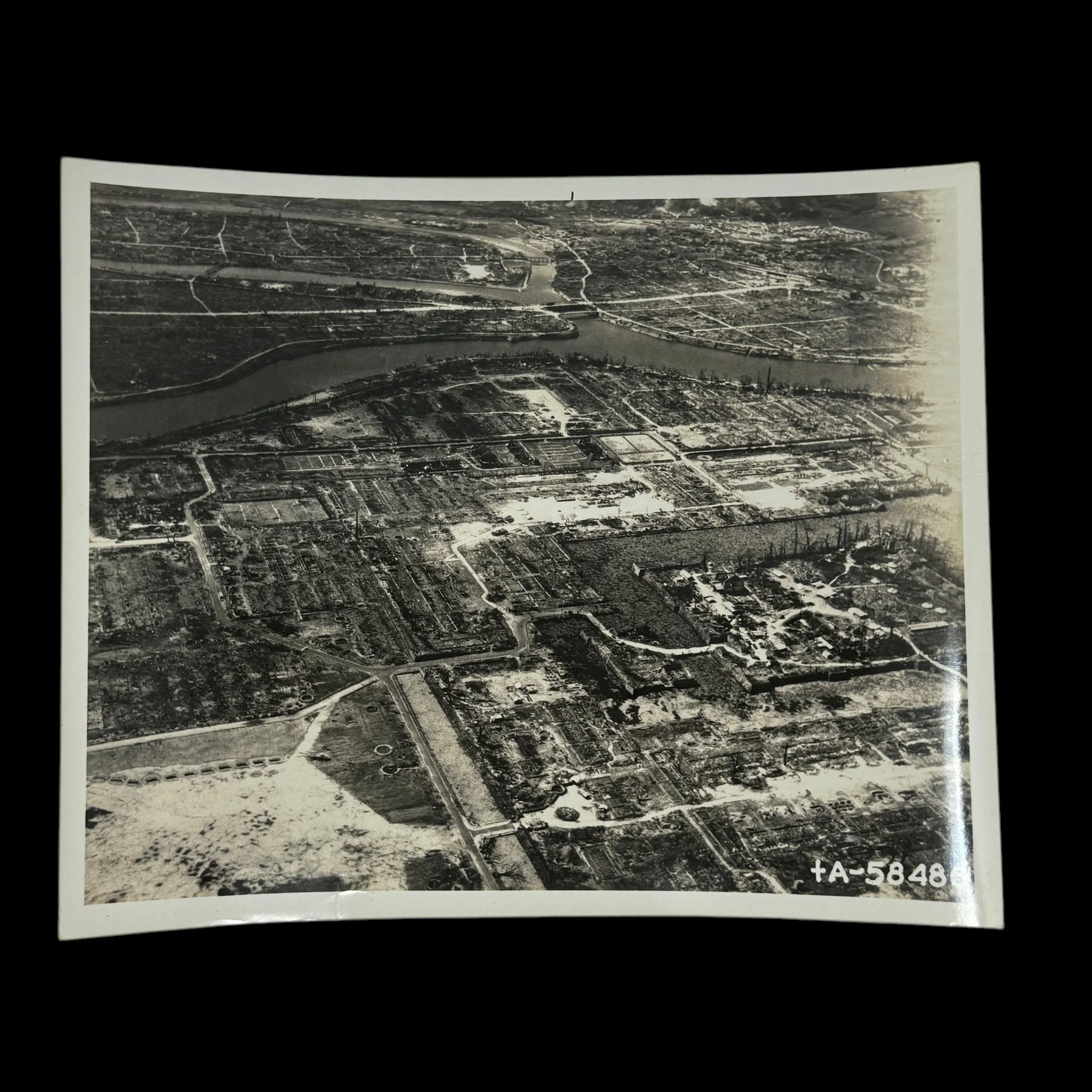

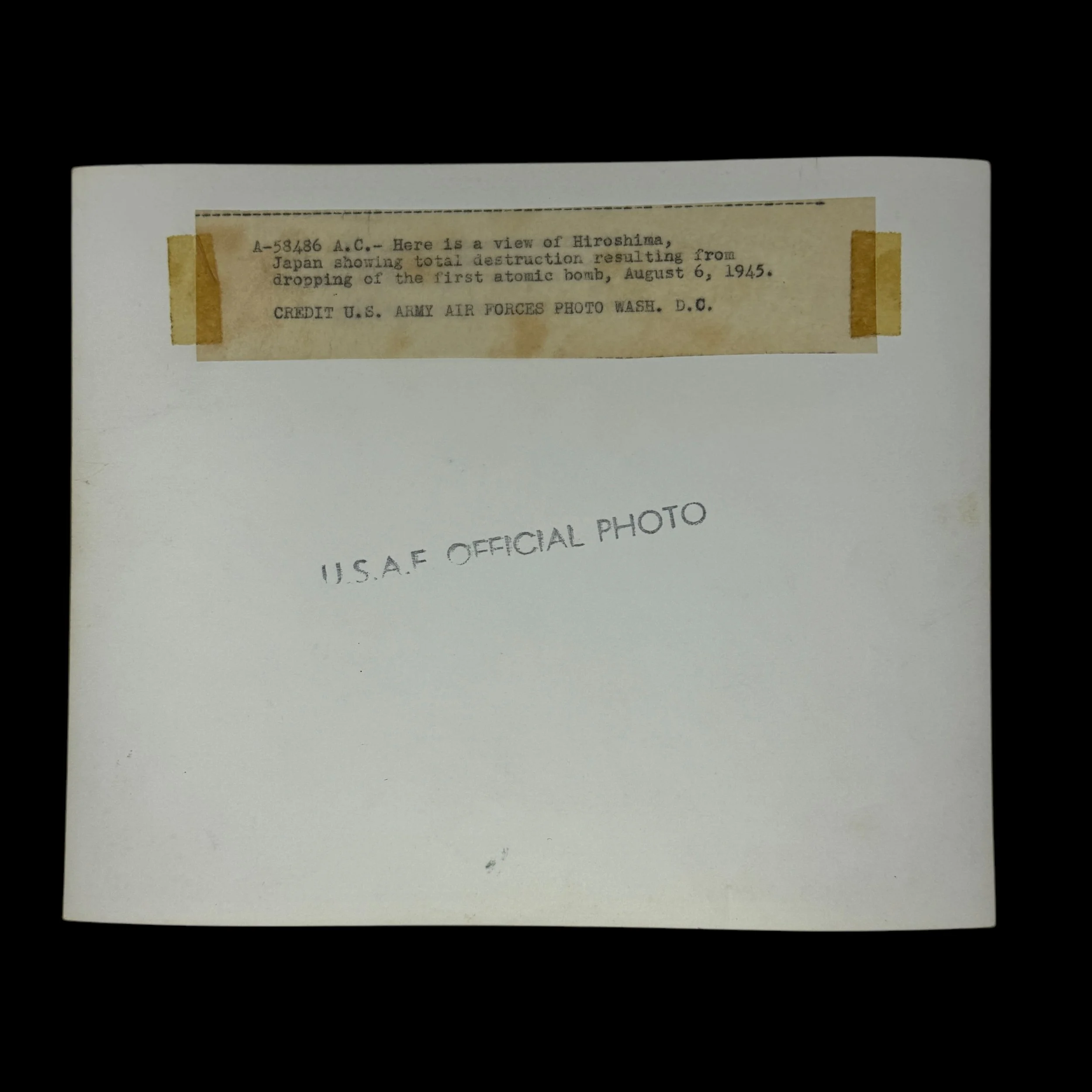

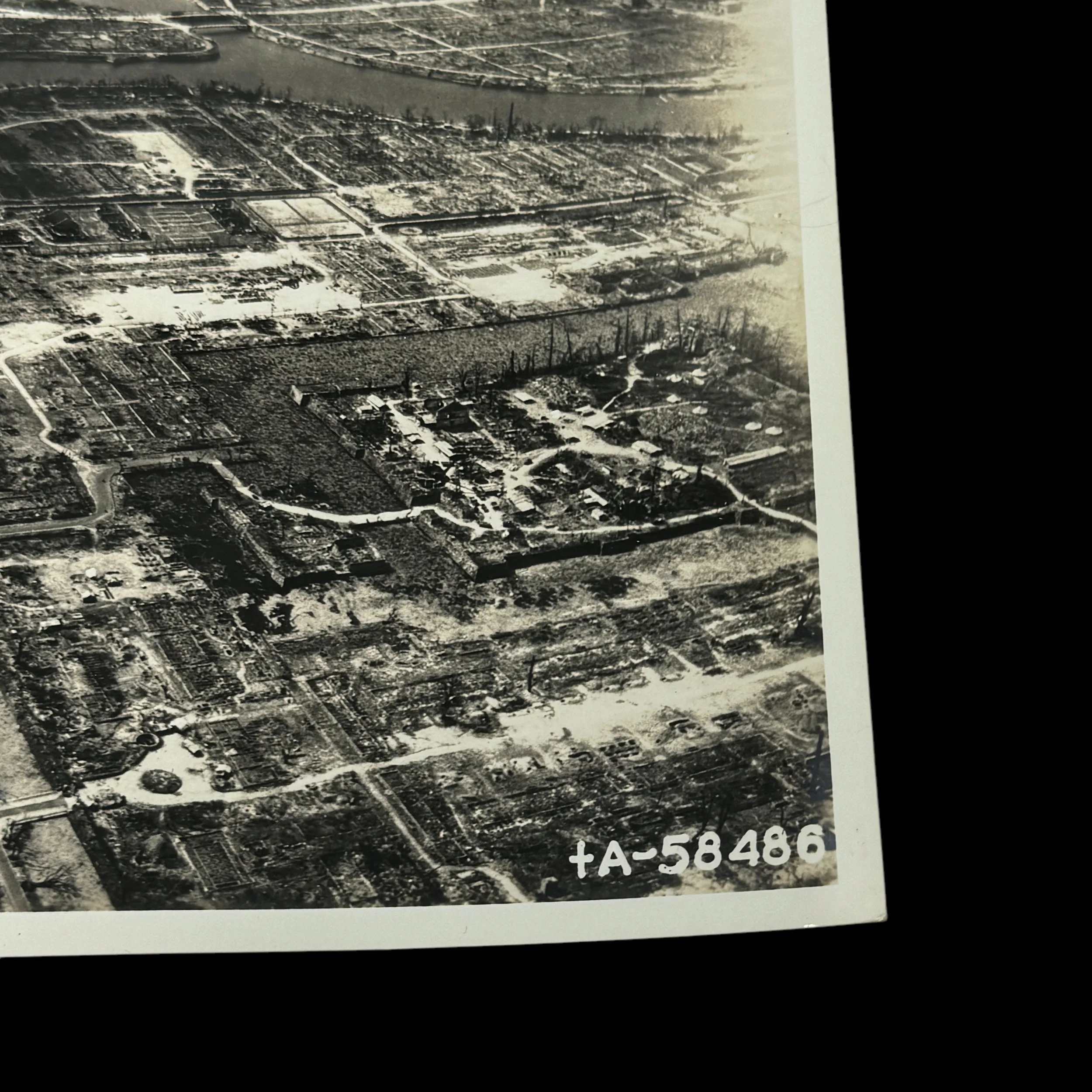

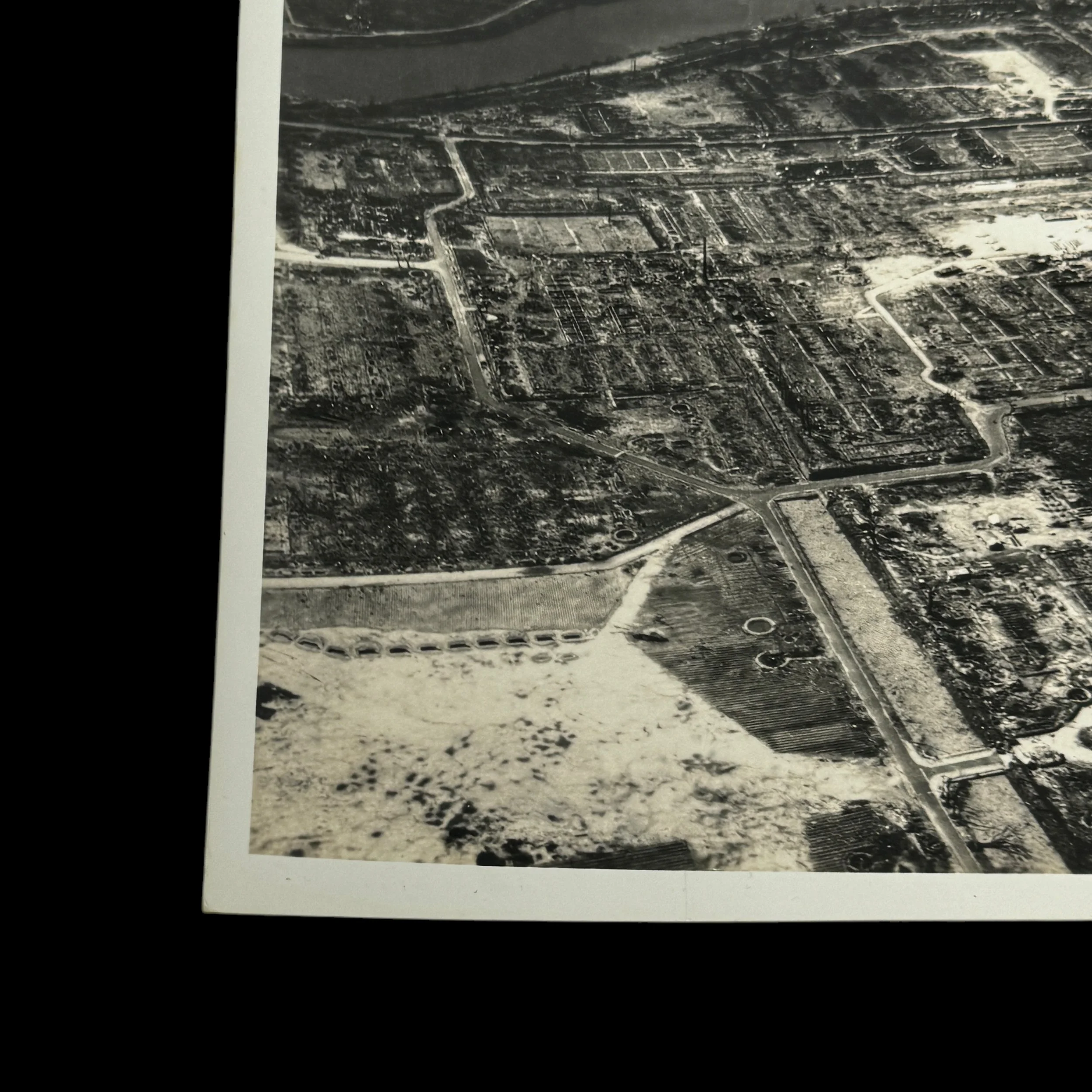

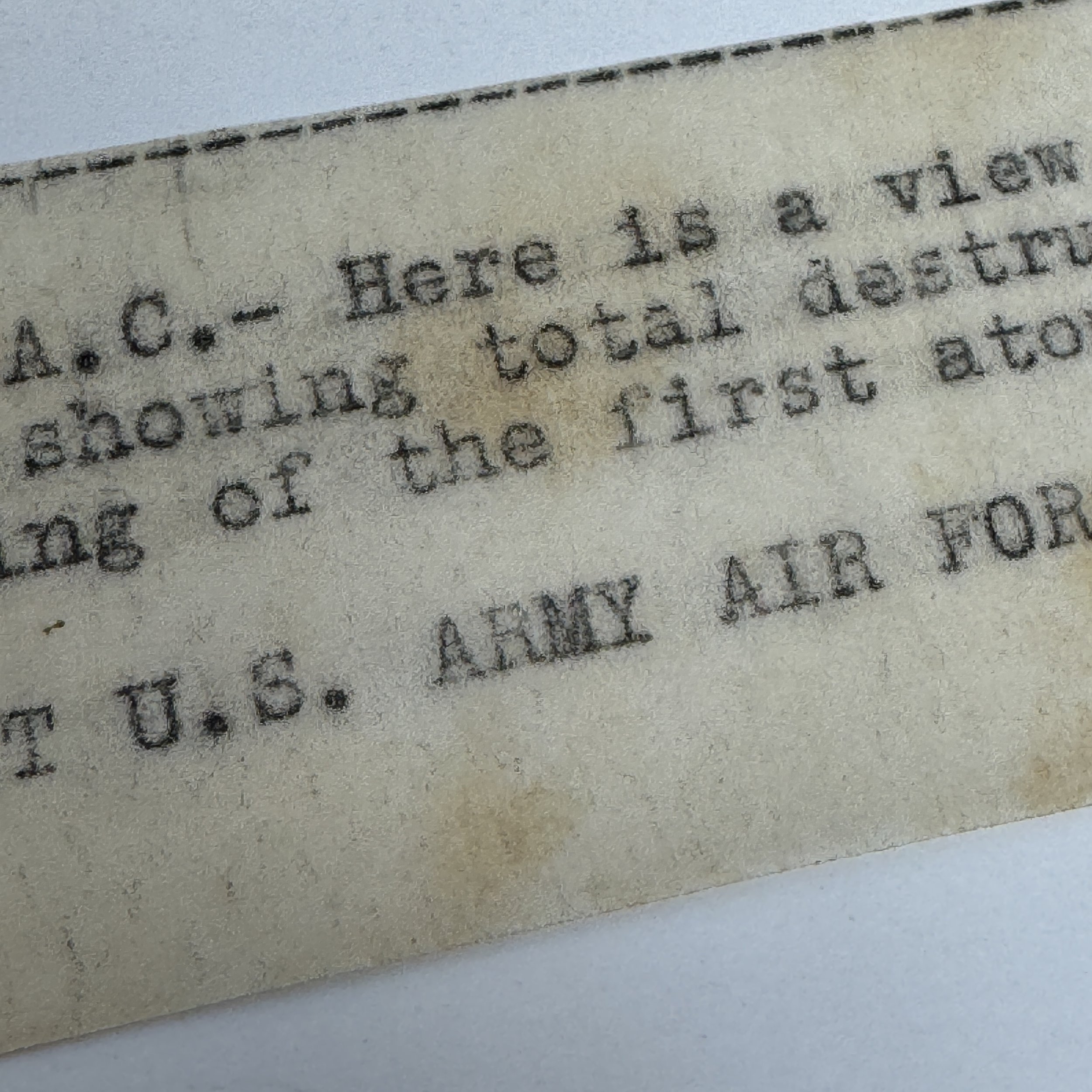

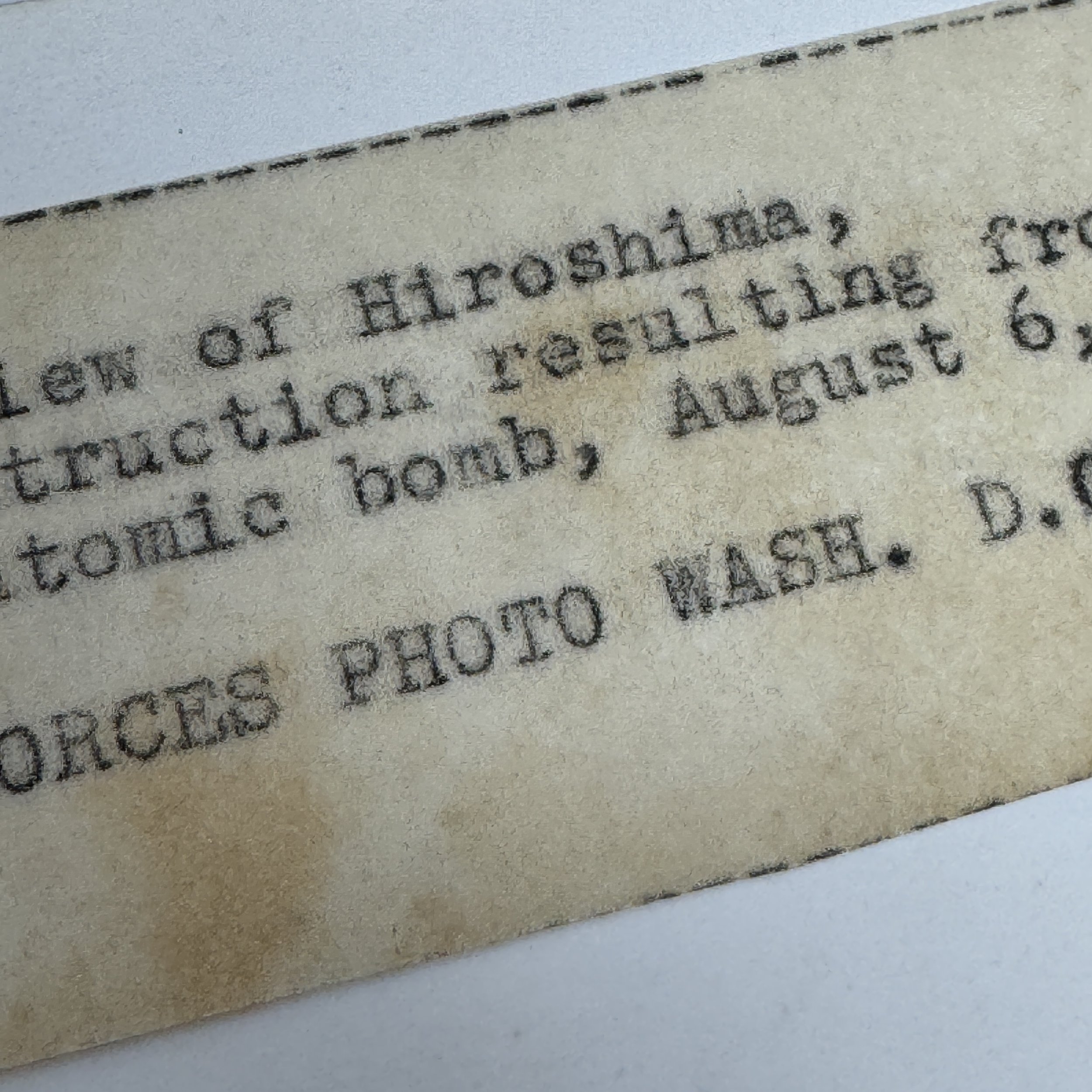

This exceptionally rare and museum-grade World War II artifact is an original Type 1 Hiroshima atomic bomb aftermath photograph, directly from the U.S. Army Air Force (Washington, D.C.). This first-edition 1945-dated military photograph is in near-mint condition and still retains the full “U.S.A.F. OFFICIAL PHOTO” black ink stamp, along with the extremely rare hand-typed fragile paper description affixed to the image. Type 1 photographs are the very first prints made from the original camera negative and were intended as master reference copies from which subsequent photographs were produced. Due to their role in military documentation, these first-generation prints were often restricted in distribution, making them among the rarest of all historical wartime photographs.

Original Hiroshima atomic bomb aftermath photographs like this are exceedingly scarce, as many were never publicly released due to the confidential and secret classification surrounding the atomic bombings. The devastation captured in these images provided critical intelligence for military assessments and historical record-keeping, but only a limited number were ever printed and preserved. Many were locked away in government archives or destroyed over time, further increasing the rarity and significance of surviving examples.

This Hiroshima damage assessment photograph represents a pivotal moment in world history, capturing the unprecedented destruction caused by the second and final atomic bomb used in warfare. Hiroshima bombing on August 6, 1945, played a key role in bringing about Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II, marking a turning point in global military history and the dawn of the nuclear age. Given its historical importance, pristine condition, and provenance, this original Type 1 photograph is a true museum-quality artifact that belongs in the hands of serious collectors, historians, and institutions dedicated to preserving the legacy of World War II.

The Manhattan Project and the Atomic Legacy: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the U.S. Army Air Force’s Pivotal Photographic Record

The Manhattan Project was one of the most ambitious and secretive scientific undertakings in history, resulting in the development of the world's first atomic bombs. Born from a mix of fear and foresight, the project began in earnest in 1939 when leading scientists, including Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, warned President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Nazi Germany might be attempting to build nuclear weapons. By 1942, the U.S. government had launched the Manhattan Project under the leadership of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves. With laboratories established in Los Alamos, New Mexico; Oak Ridge, Tennessee; and Hanford, Washington, the project employed over 130,000 people and cost nearly $2 billion (equivalent to over $25 billion today). The scientific achievement was unprecedented: successfully harnessing nuclear fission in a weaponized form through two different designs—the uranium-based "Little Boy" and the plutonium-based "Fat Man."

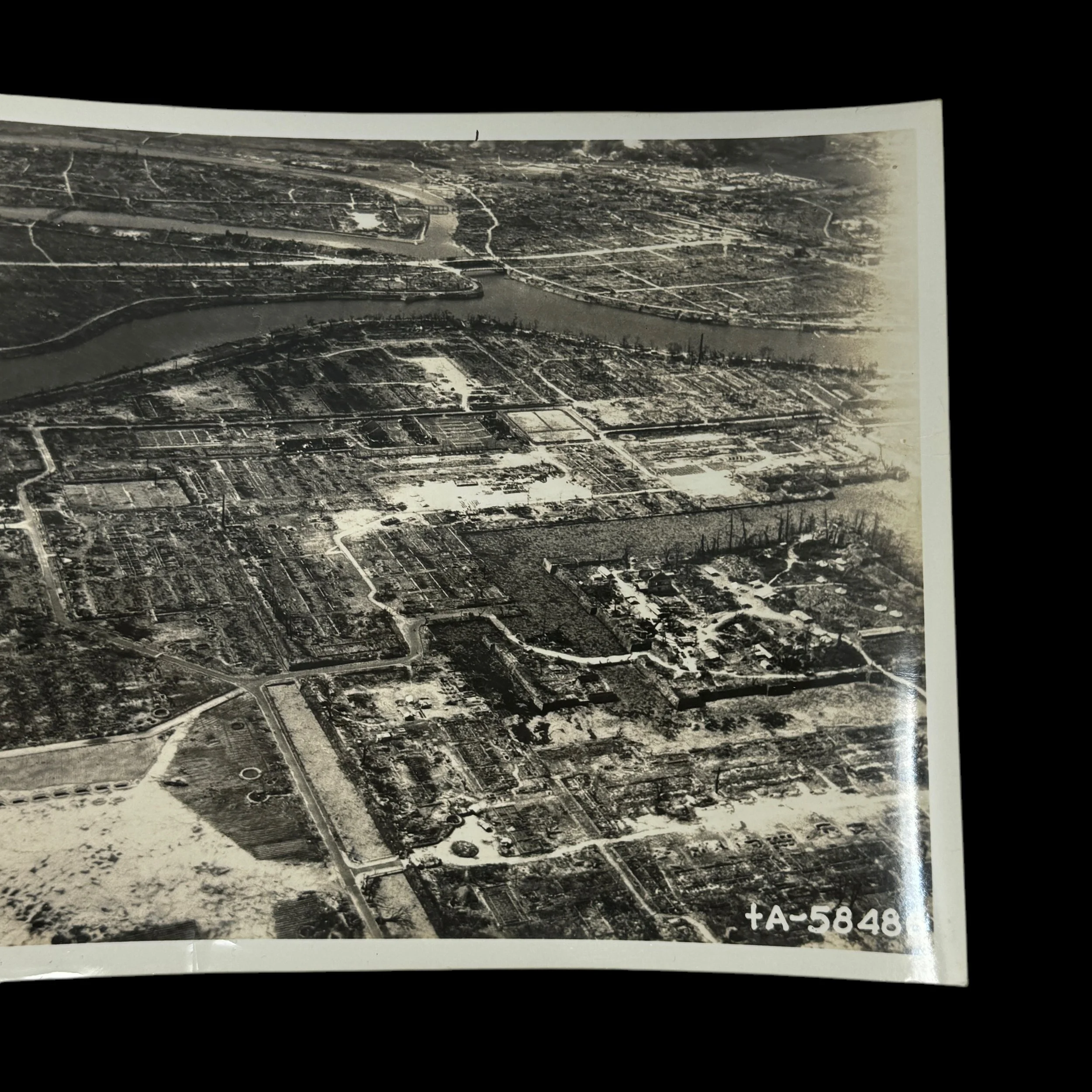

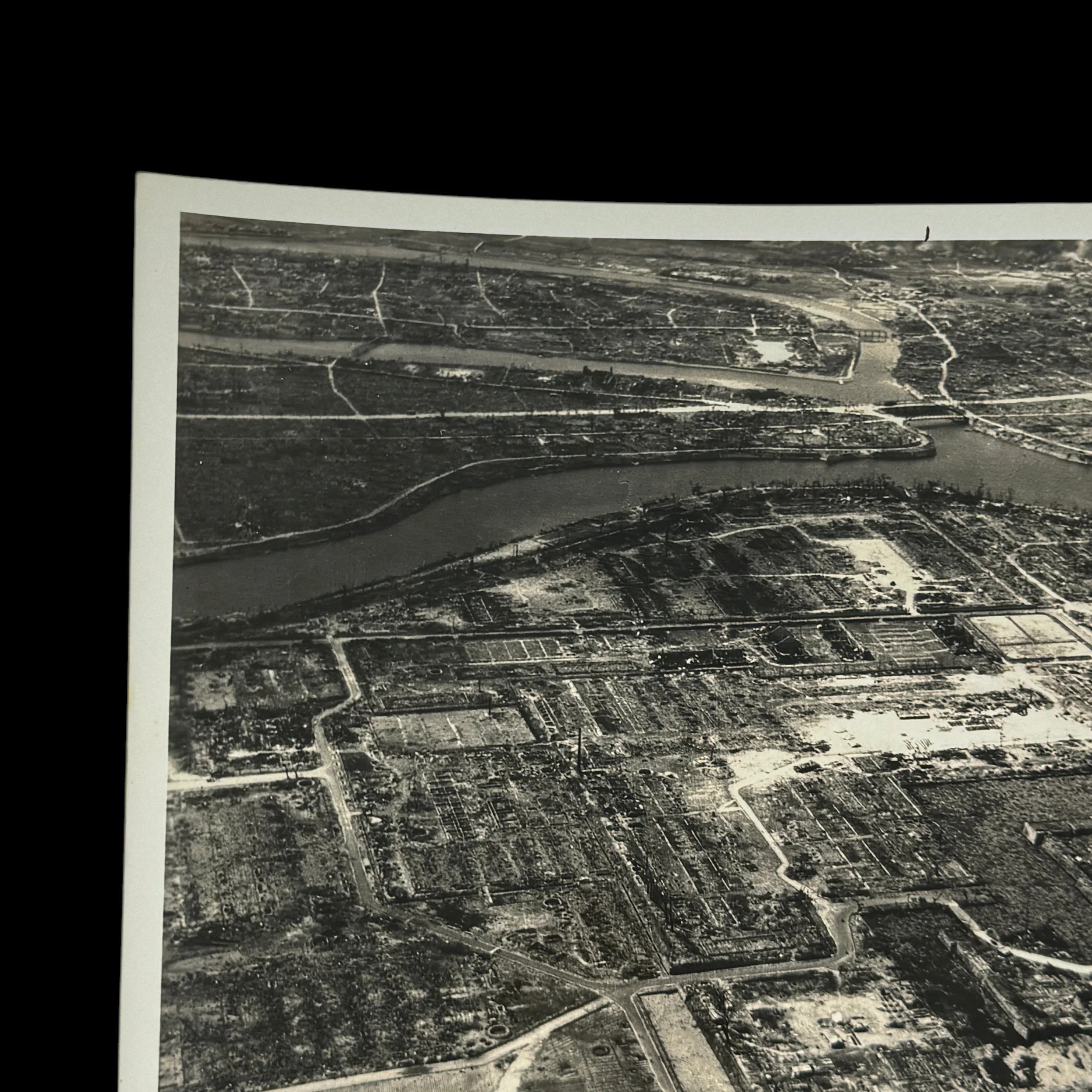

As World War II raged on, the United States faced the daunting prospect of a land invasion of Japan, which promised to be bloody and prolonged. After the successful test of the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Site on July 16, 1945, U.S. military and political leaders, including President Harry S. Truman, were convinced that the use of these new weapons could force Japan into surrender without a costly invasion. On August 6, 1945, the B-29 SuperfortressEnola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets, dropped the "Little Boy" bomb on Hiroshima, a major military-industrial center in western Japan. The bomb detonated approximately 1,900 feet above the city with a yield of around 15 kilotons, instantly flattening more than four square miles of the city and killing an estimated 70,000 people outright, with tens of thousands more succumbing to radiation burns, injuries, and disease in the following weeks and months.

Three days later, on August 9, the U.S. dropped the "Fat Man" bomb on Nagasaki, another strategic target. This bomb, although more powerful—yielding approximately 21 kilotons—was less destructive due to Nagasaki’s more mountainous terrain. Nevertheless, around 40,000 people were killed instantly, with the total death toll eventually rising to around 70,000. The shock of the bombings, compounded with the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan and invasion of Manchuria, finally led Emperor Hirohito to announce Japan’s unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, effectively ending World War II.

Integral to the historical documentation and interpretation of the bombings were the photographs taken by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) from both the air and the ground. These photographs served multiple roles—military intelligence, scientific analysis, propaganda, and post-war historical record. During the bombing missions, specially equipped reconnaissance aircraft flew alongside the bombers to photograph the target areas before, during, and after the detonations. One of the most iconic images from the Hiroshima bombing shows the vast, rising mushroom cloud that loomed over the city moments after detonation. These aerial images were crucial for assessing the bomb’s impact radius, structural destruction, and cloud dispersion patterns, providing immediate data to military scientists and strategists.

In the weeks and months that followed, ground-level reconnaissance teams and scientific survey groups—such as those from the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey—entered Hiroshima and Nagasaki to gather further documentation. They photographed leveled neighborhoods, twisted steel structures, scorched earth, and the haunting shadows of people permanently burned into stone by the intense thermal radiation. These photos, often stark and harrowing, helped quantify the bomb’s effects on buildings, infrastructure, and human life. Some photographs were classified and used internally to understand the bomb’s mechanics, while others were released to the public to illustrate the power of the new atomic age. Their use was also strategic; they were employed to justify the bombings as necessary to end the war swiftly and to act as a deterrent in the early stages of the Cold War.

Perhaps most poignantly, these photographs also played a role in the emerging discourse on nuclear ethics and the morality of atomic warfare. The visual record of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s obliteration—both from above and on the ground—ensured that the horror of atomic war could not be ignored or abstracted. The images captured by the U.S. Army Air Forces are not just historical documents; they are visual witnesses to one of humanity’s most profound and devastating achievements—ushering in a new era of warfare and forever altering the course of world history.