RARE! WWII August 1945 Type 1 U.S. Army Air Force Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Damage Assessment Aftermath Photograph

RARE! WWII August 1945 Type 1 U.S. Army Air Force Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Damage Assessment Aftermath Photograph

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

Size: 7 and 1/2 × 9 and 1/8 inches

Type: First Edition - Type 1 Photograph

Subject: Nagasaki Atomic Bomb - U.S.A.F. Damage Assessment Aftermath

Dated: August 1945

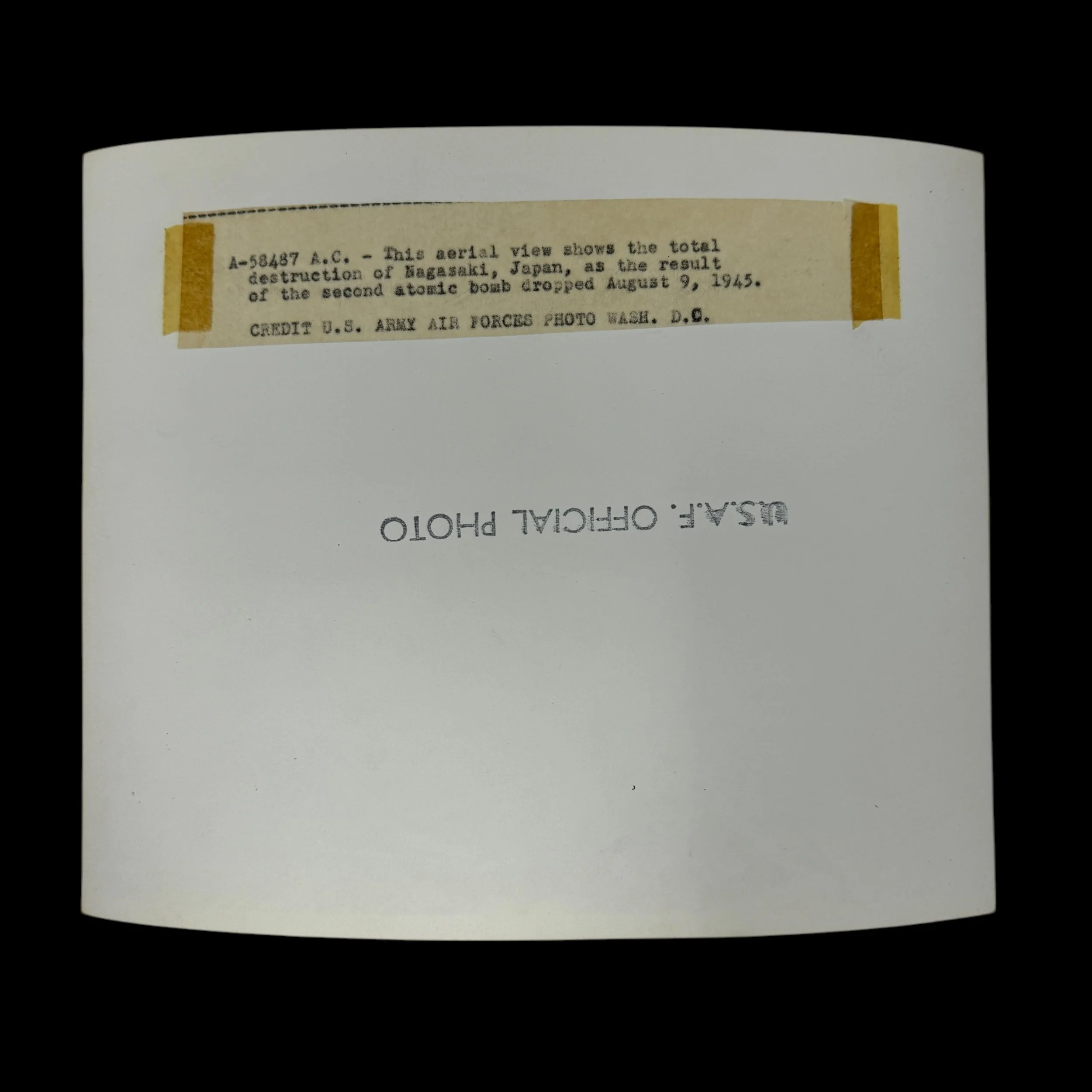

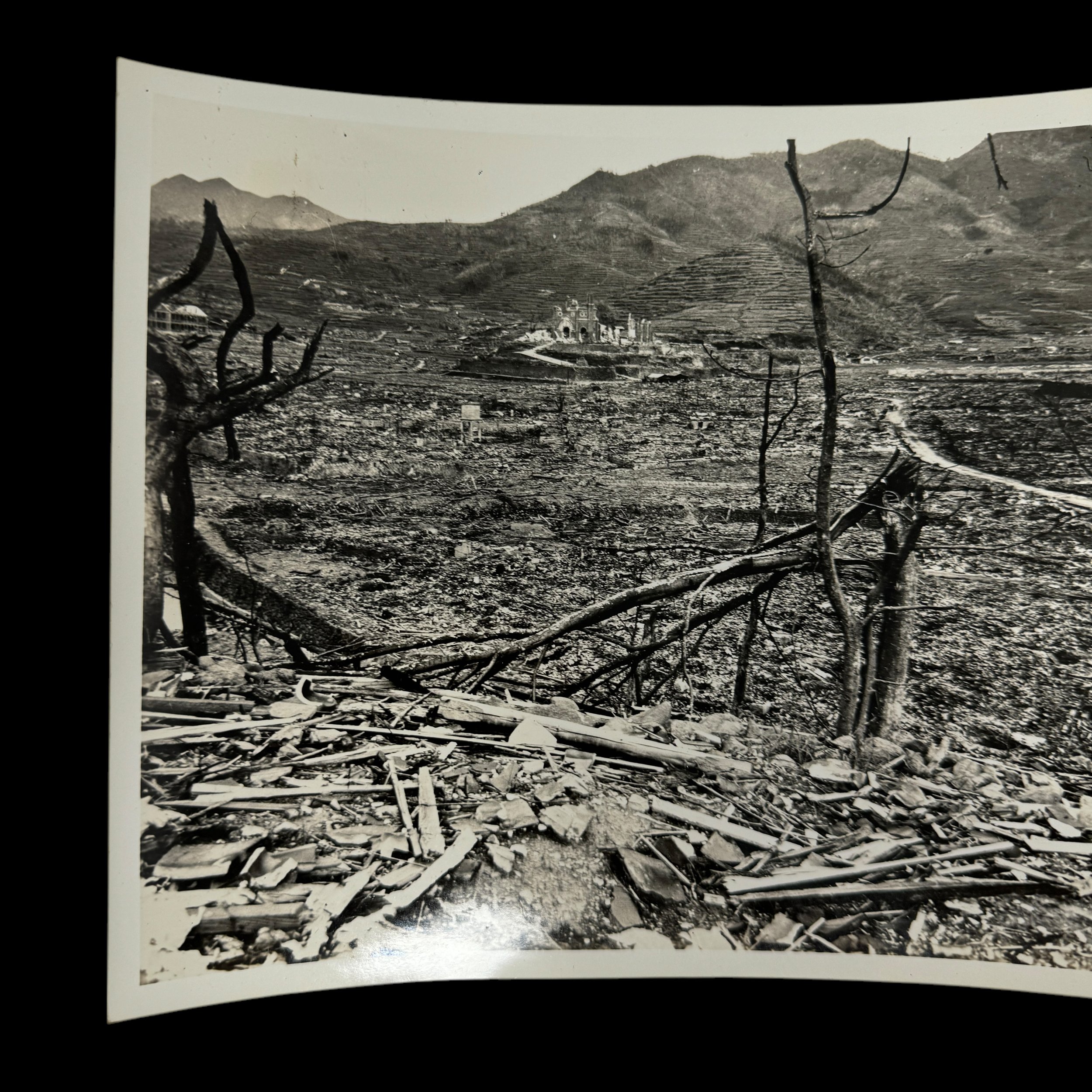

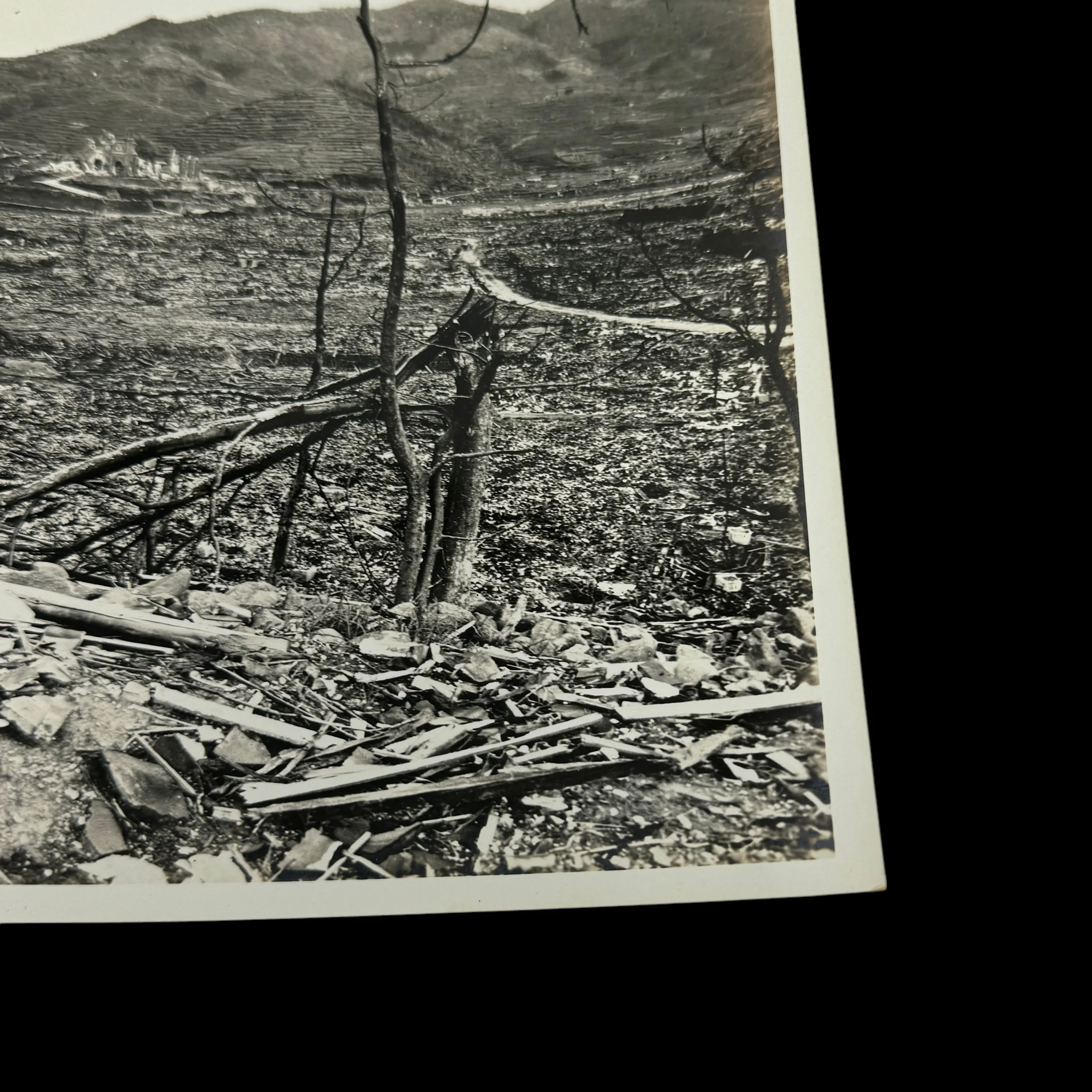

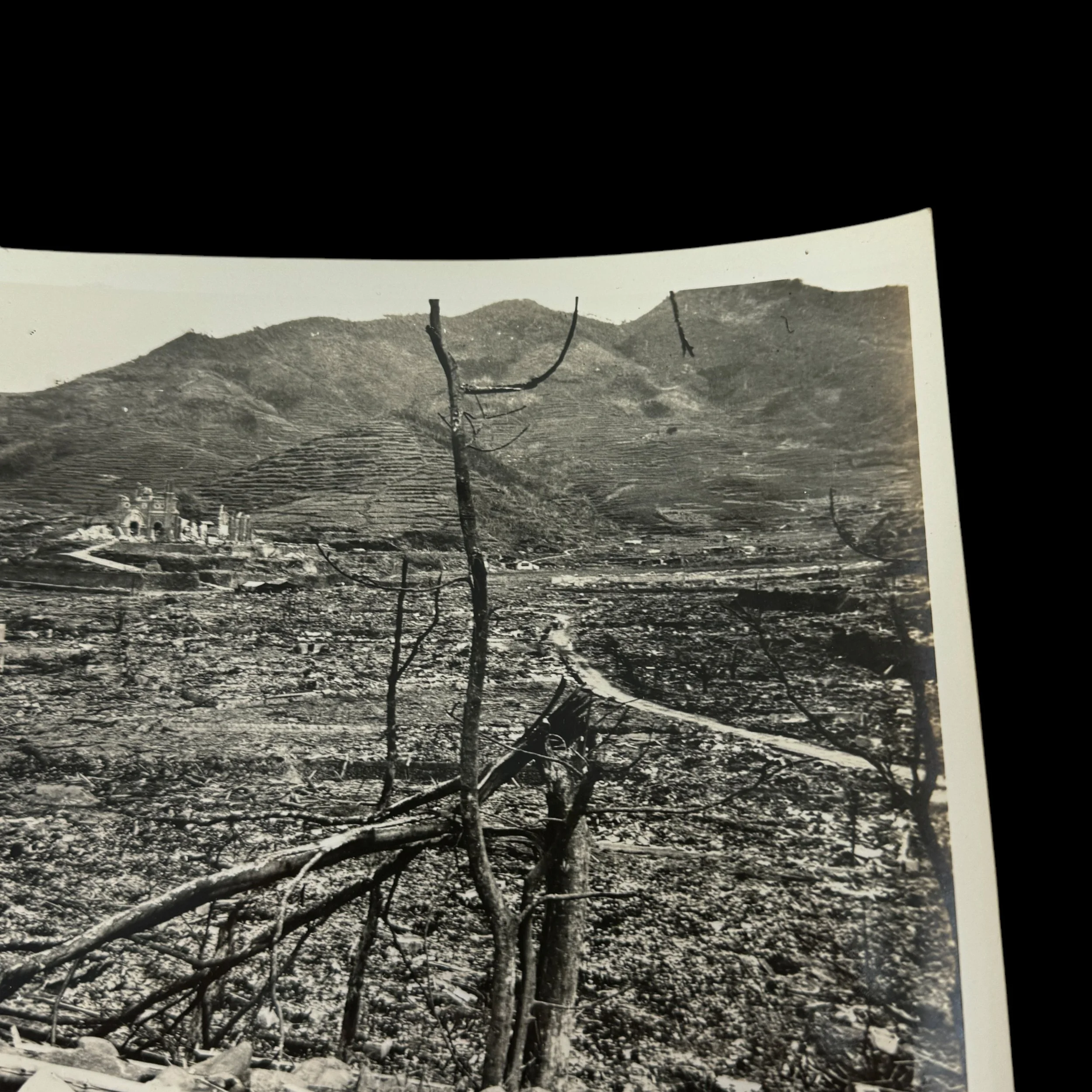

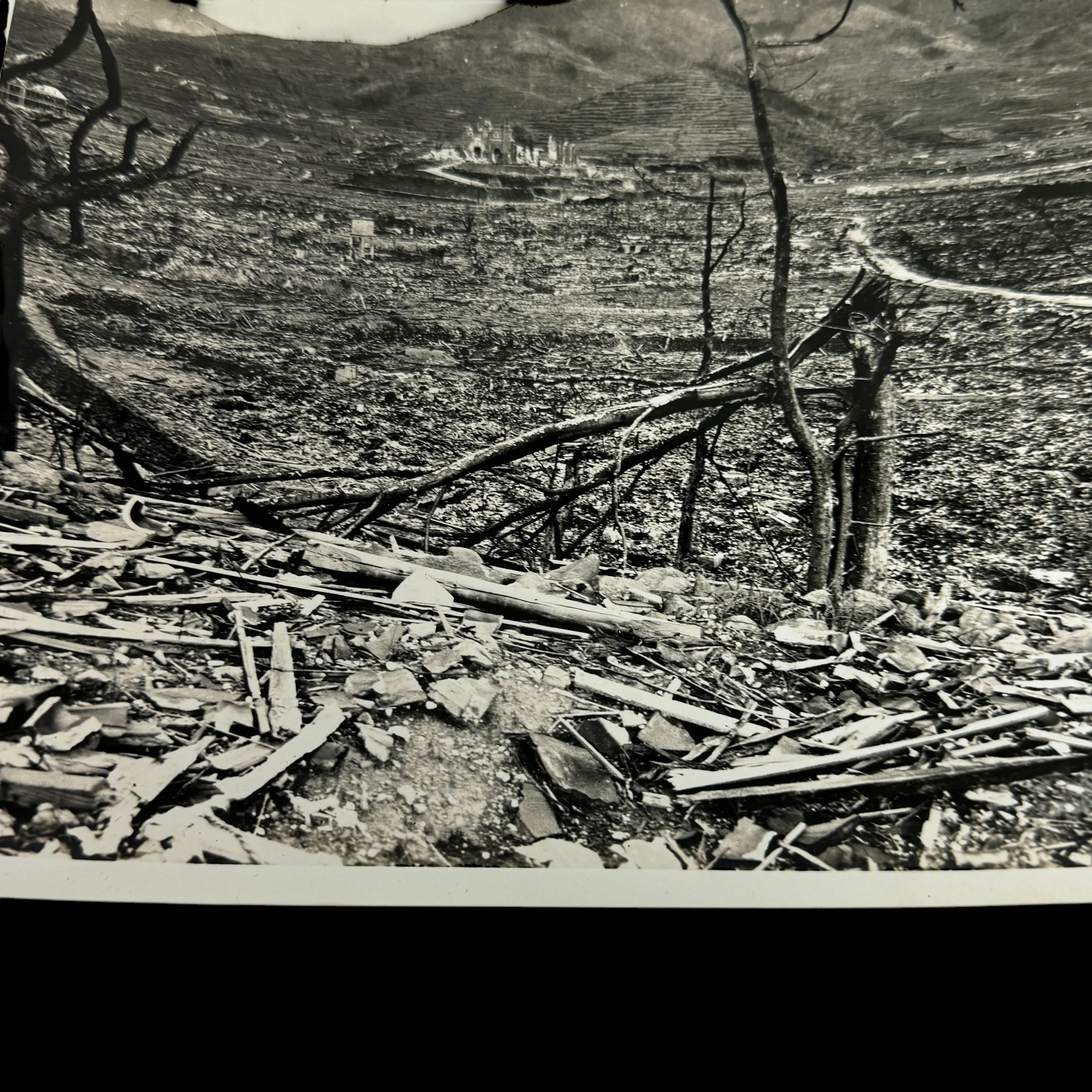

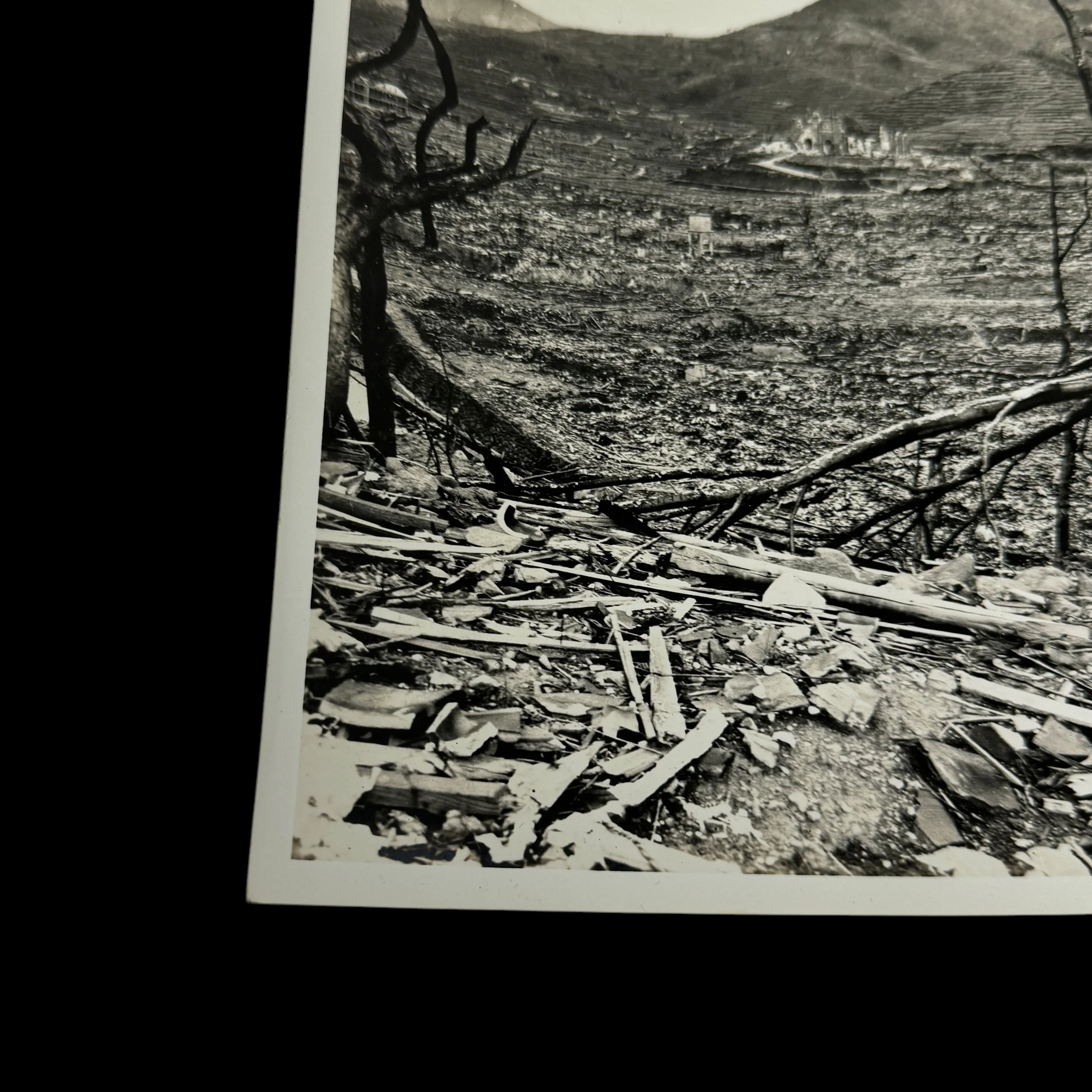

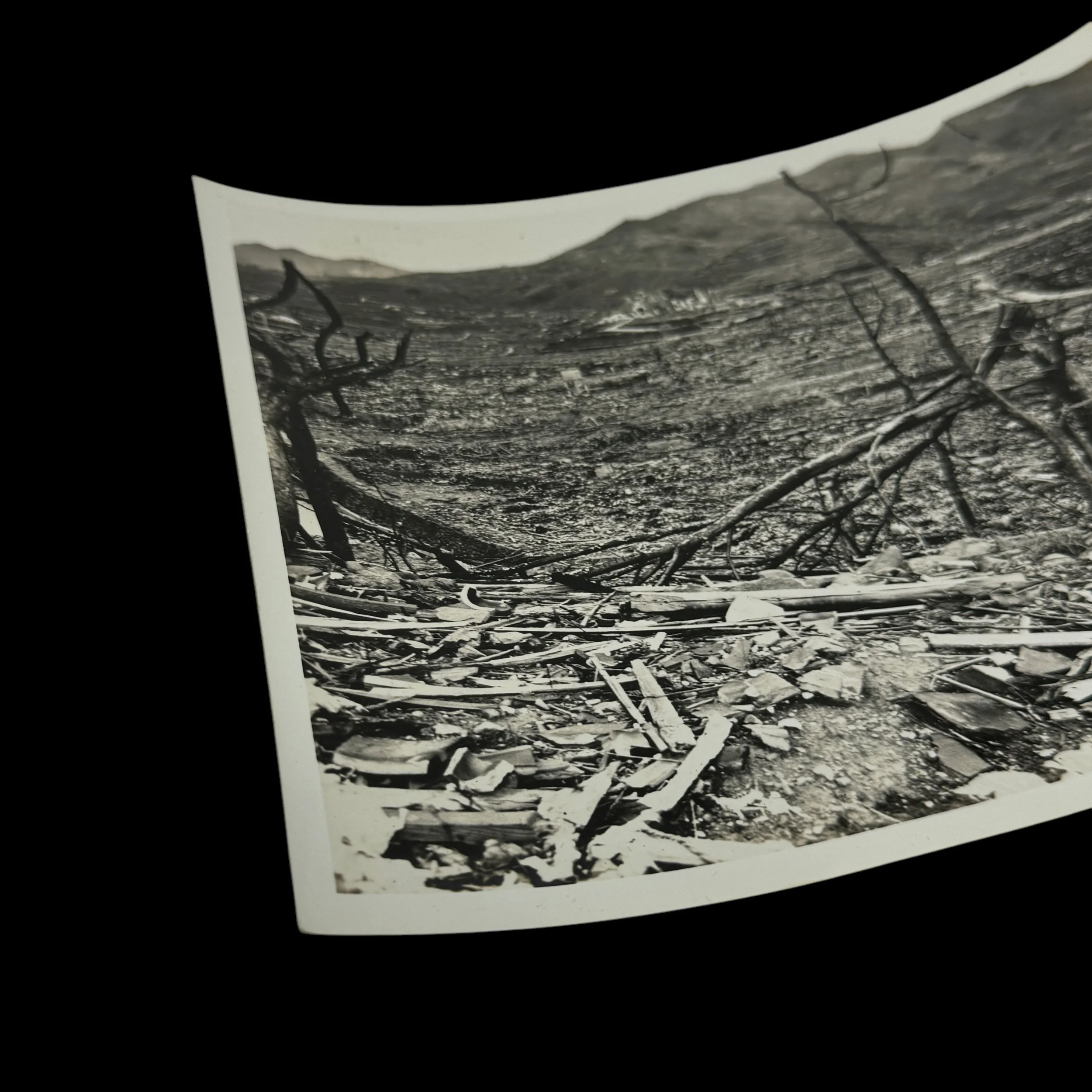

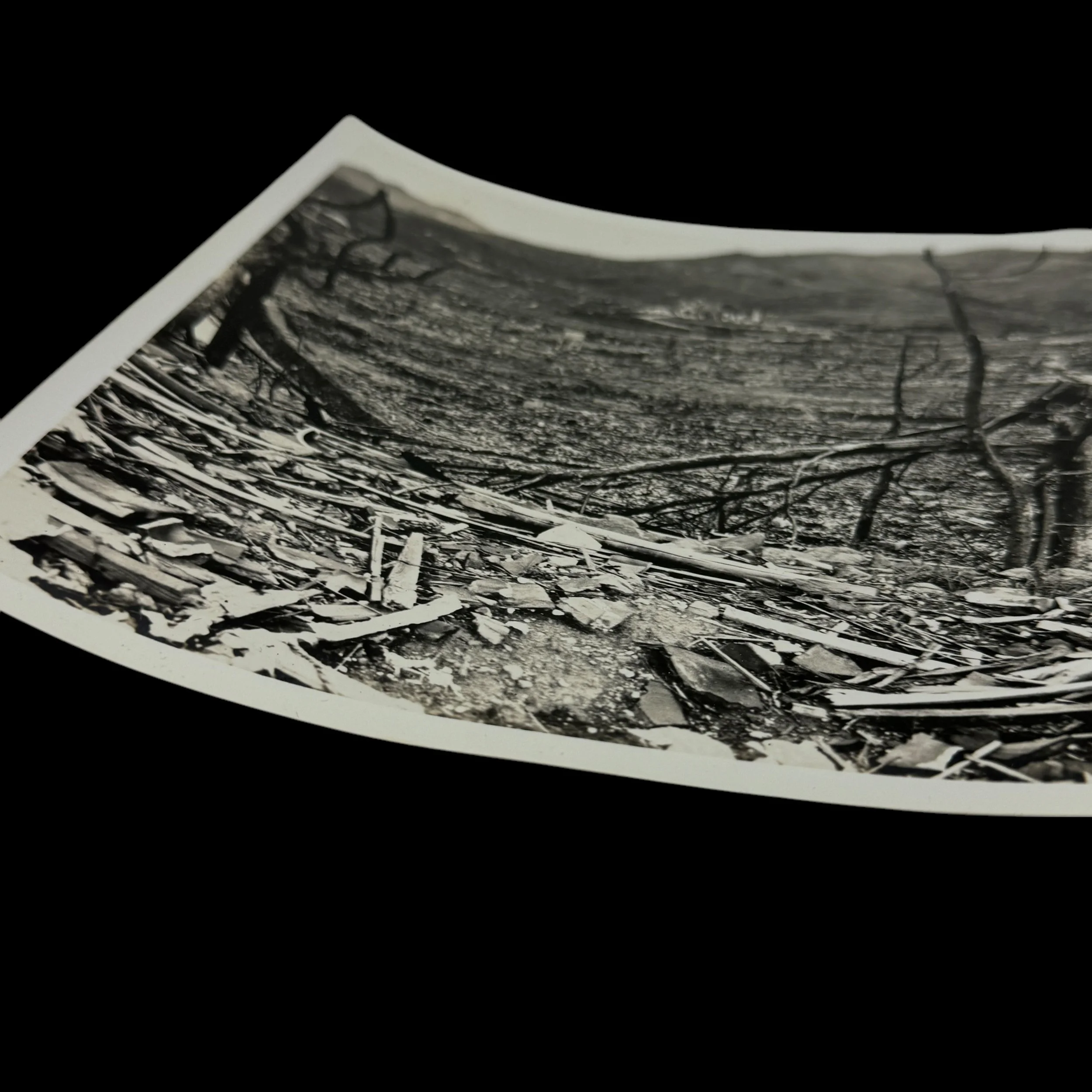

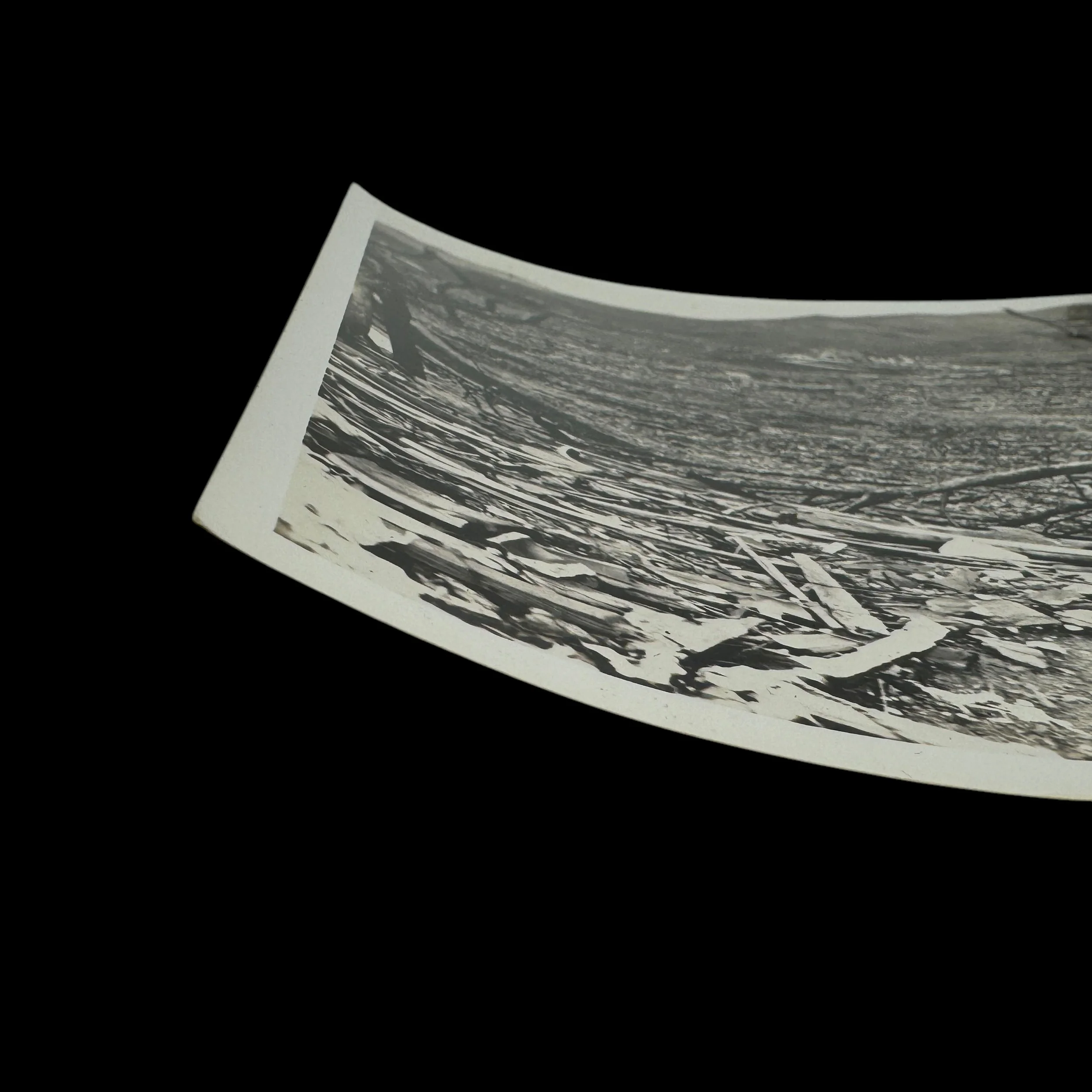

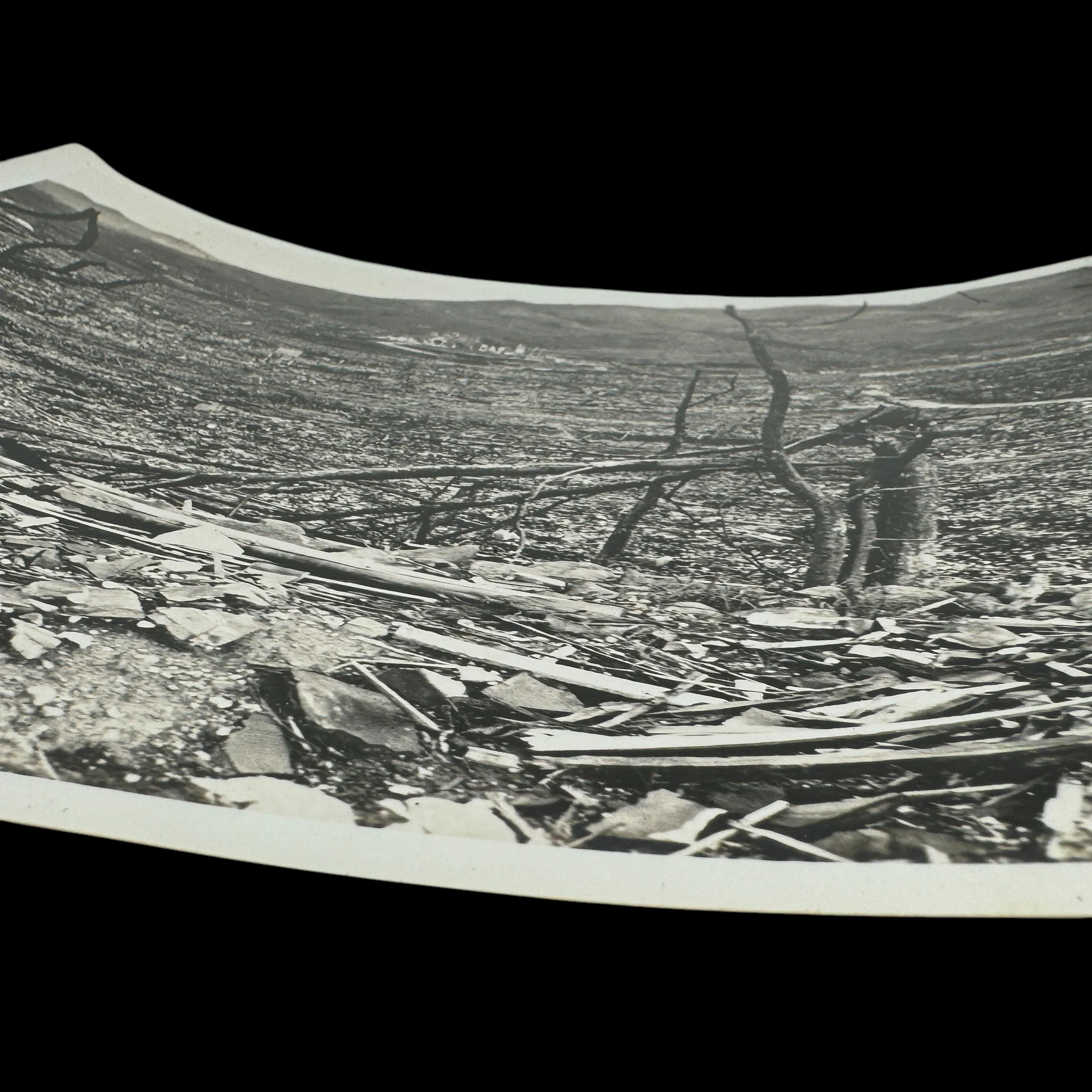

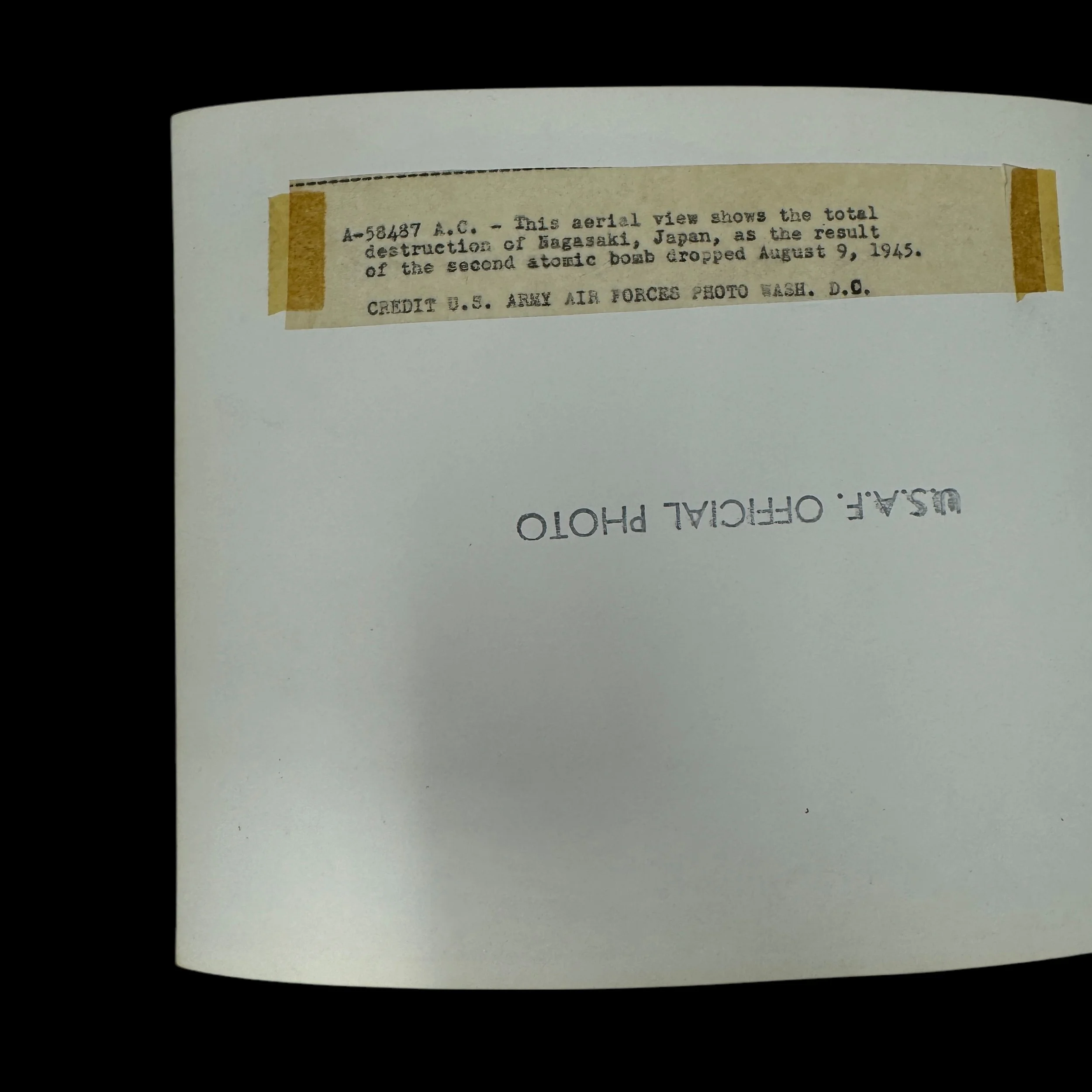

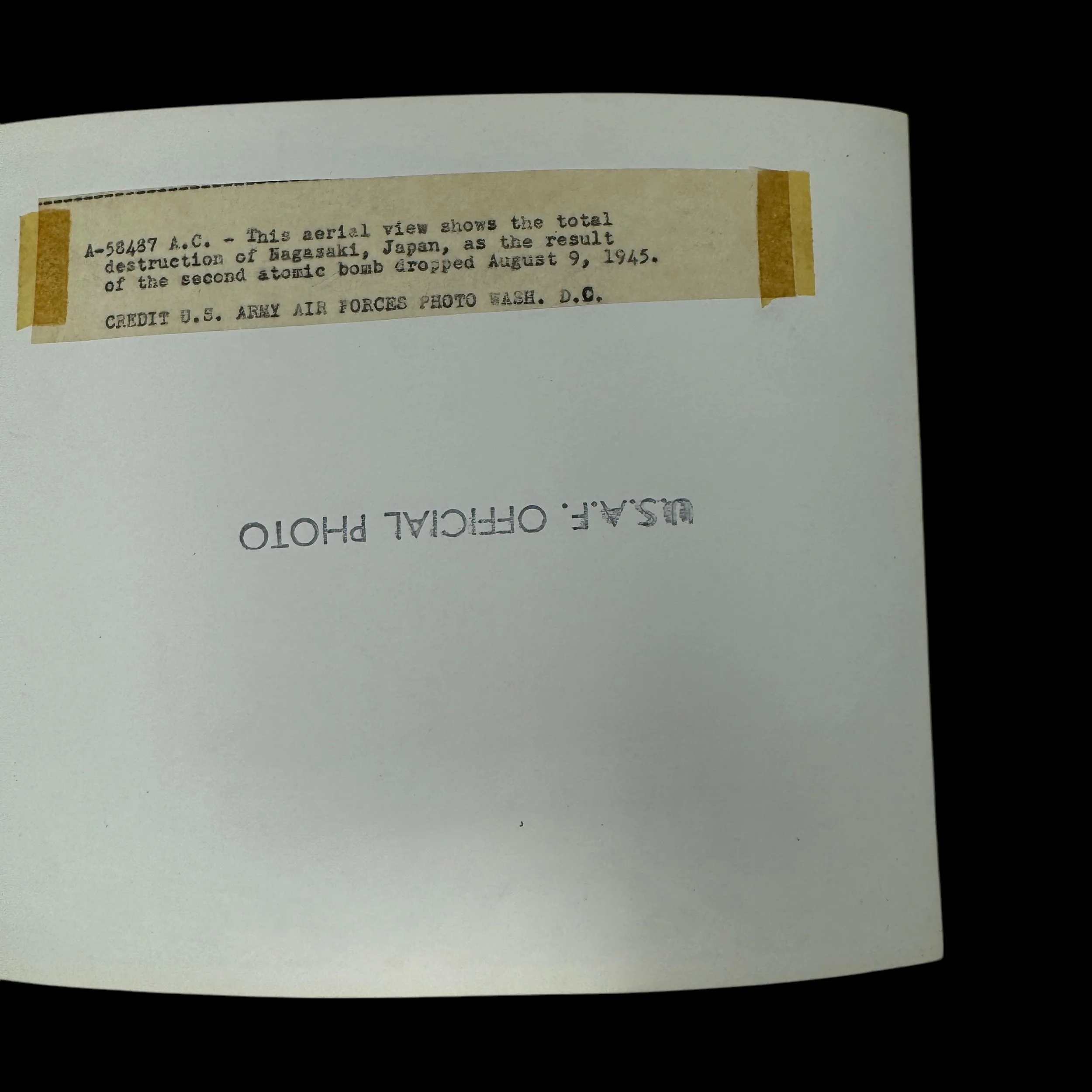

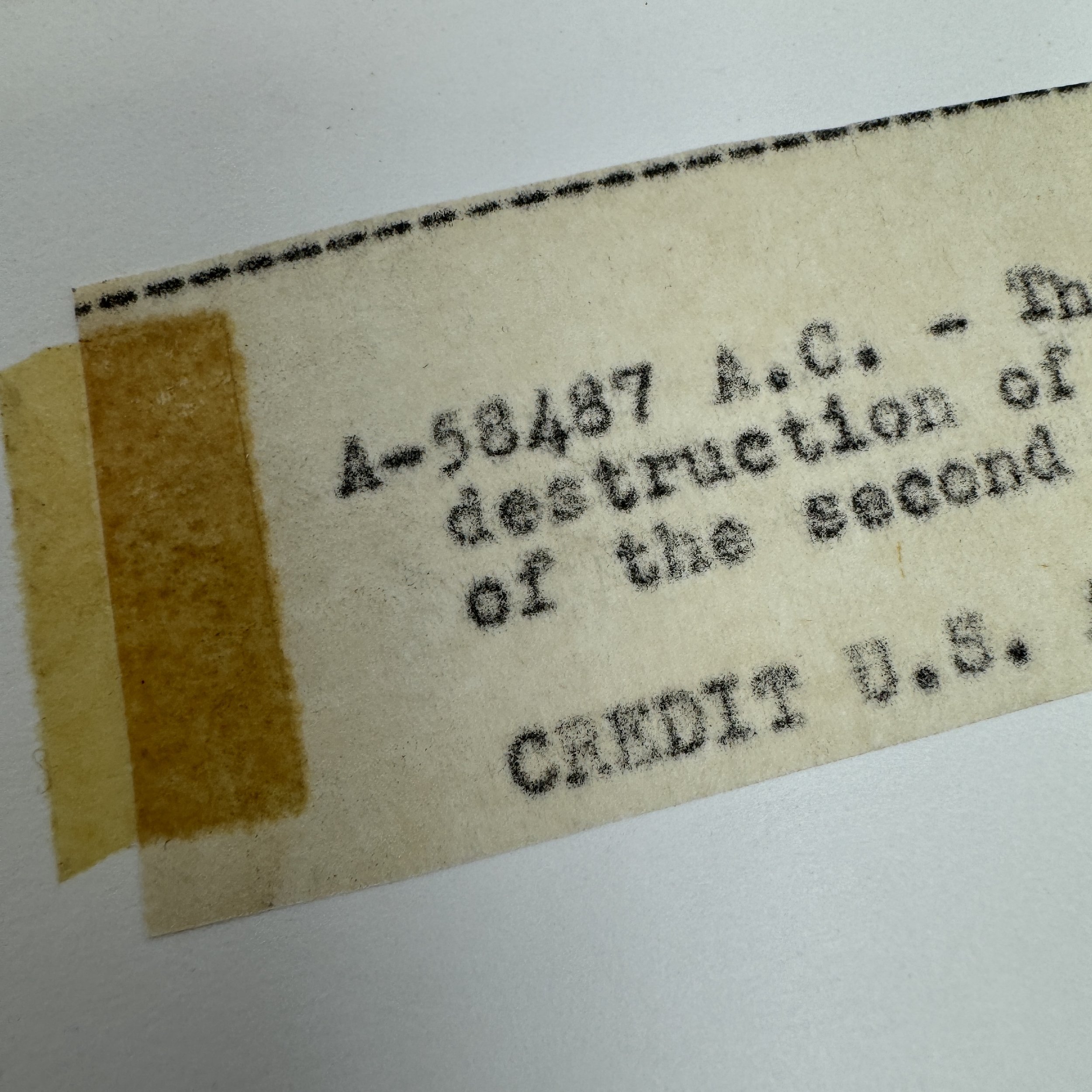

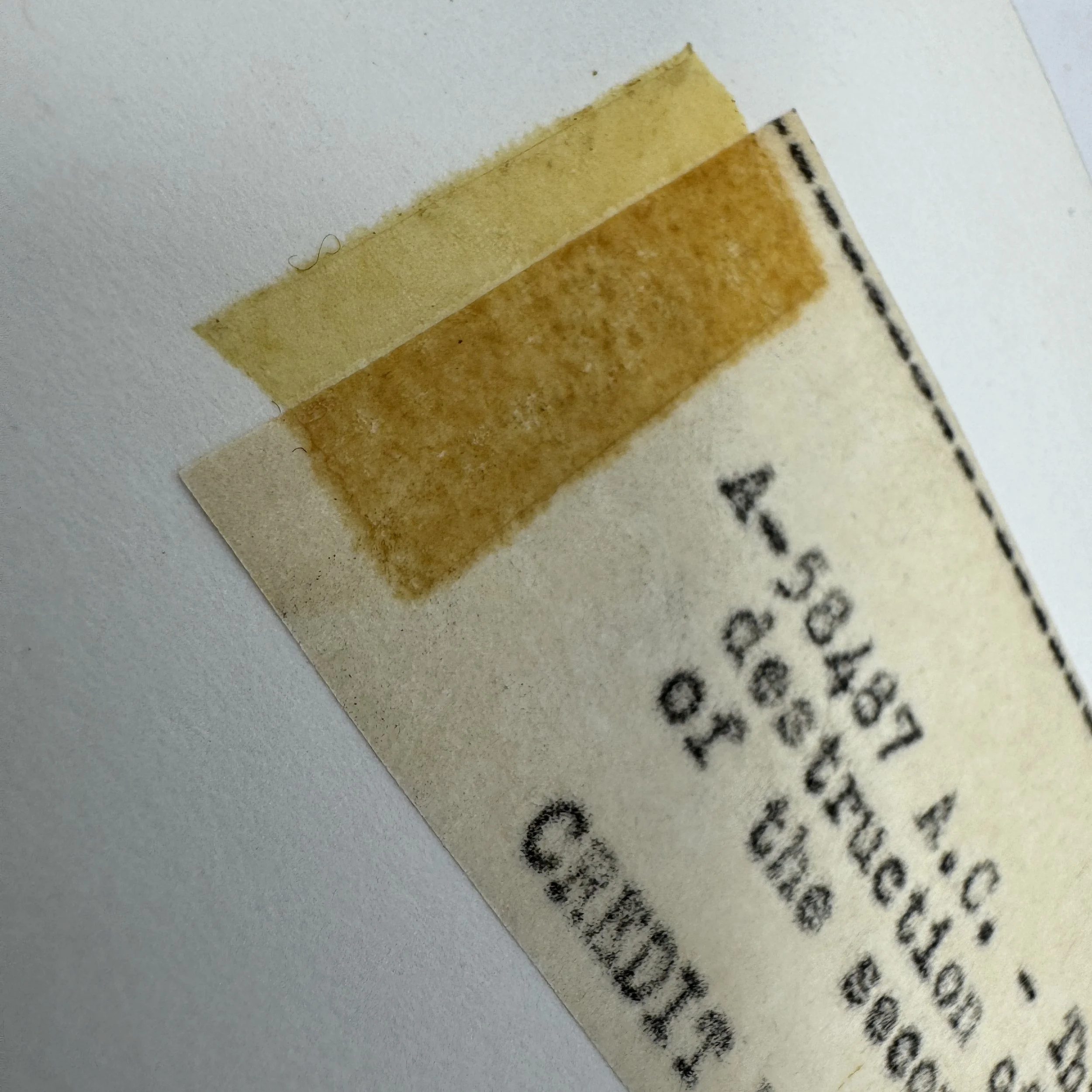

This exceptionally rare and museum-grade World War II artifact is an original Type 1 Nagasaki atomic bomb aftermath photograph, directly from the U.S. Army Air Force (Washington, D.C.). This first-edition 1945-dated military photograph is in near-mint condition and still retains the full “U.S.A.F. OFFICIAL PHOTO” black ink stamp, along with the extremely rare hand-typed fragile paper description affixed to the image. Type 1 photographs are the very first prints made from the original camera negative and were intended as master reference copies from which subsequent photographs were produced. Due to their role in military documentation, these first-generation prints were often restricted in distribution, making them among the rarest of all historical wartime photographs.

Original Nagasaki atomic bomb aftermath photographs like this are exceedingly scarce, as many were never publicly released due to the confidential and secret classification surrounding the atomic bombings. The devastation captured in these images provided critical intelligence for military assessments and historical record-keeping, but only a limited number were ever printed and preserved. Many were locked away in government archives or destroyed over time, further increasing the rarity and significance of surviving examples.

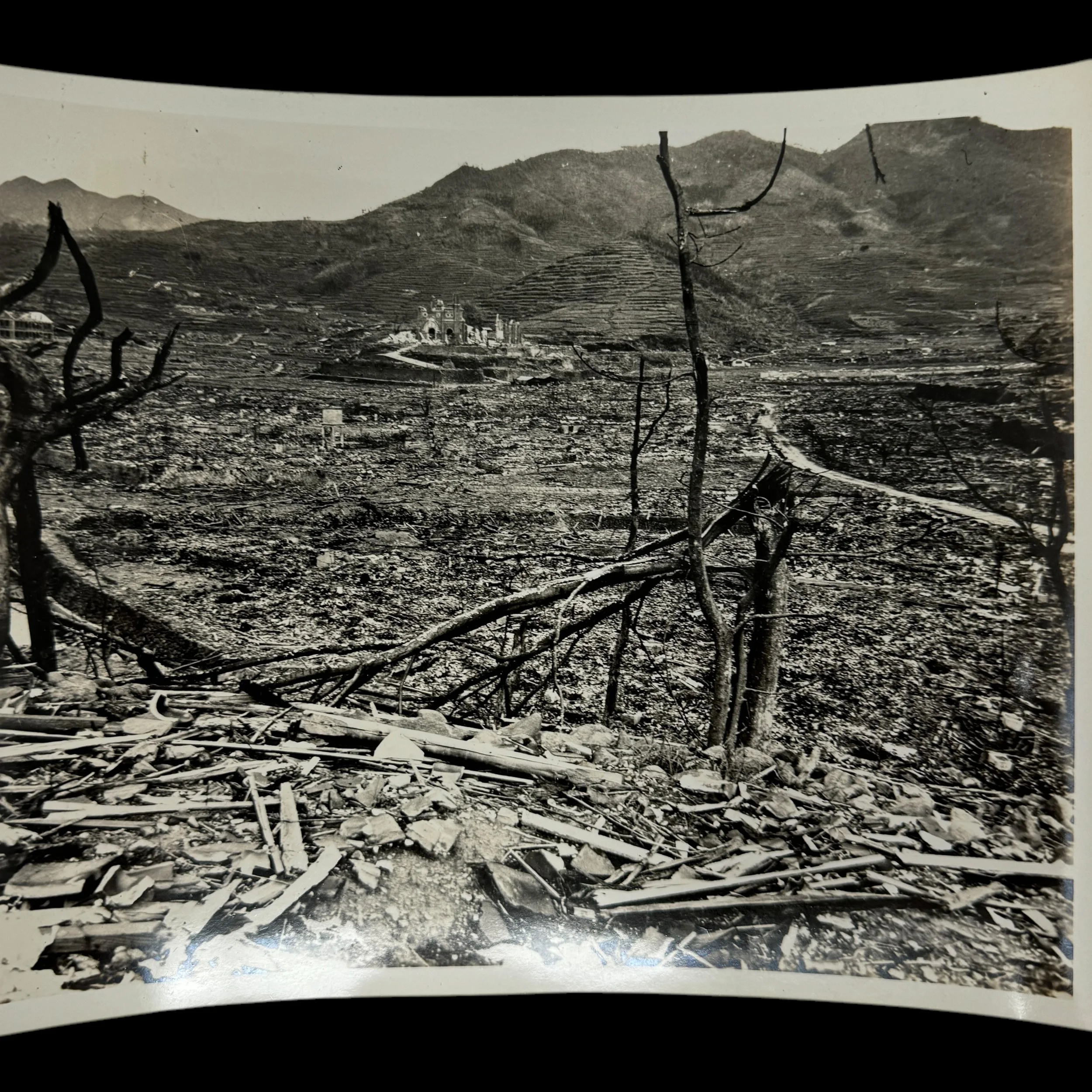

This Nagasaki damage assessment photograph represents a pivotal moment in world history, capturing the unprecedented destruction caused by the second and final atomic bomb used in warfare. Nagasaki’s bombing on August 9, 1945, played a key role in bringing about Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II, marking a turning point in global military history and the dawn of the nuclear age. Given its historical importance, pristine condition, and provenance, this original Type 1 photograph is a true museum-quality artifact that belongs in the hands of serious collectors, historians, and institutions dedicated to preserving the legacy of World War II.

Shadows of Destruction: The Manhattan Project and the Photographic Legacy of Nagasaki:

The Manhattan Project stands as one of the most monumental and controversial scientific and military endeavors in human history. Initiated in 1939 and officially organized in 1942, the project was a secret U.S.-led initiative to develop nuclear weapons before Nazi Germany could achieve the same. With the backing of the U.S. government and participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, the project gathered some of the greatest scientific minds of the time—including J. Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, and Niels Bohr. Its primary research and development facility was located in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where under strict secrecy, a new form of warfare was born. The Manhattan Project successfully produced two types of atomic bombs: "Little Boy," a uranium-based device, and "Fat Man," which used plutonium. These weapons would eventually be dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, changing the course of warfare and global politics forever.

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb, Little Boy, on Hiroshima. The impact was immediate and catastrophic, obliterating nearly everything within a one-mile radius and killing an estimated 70,000 to 80,000 people instantly, with tens of thousands more dying in the following weeks and months due to radiation sickness and injuries. Despite this devastating demonstration of nuclear power, the Japanese government did not immediately surrender. On August 9, 1945, the U.S. dropped a second bomb, Fat Man, on the city of Nagasaki, a critical industrial hub and port. The city’s topography, nestled between mountains and valleys, somewhat contained the blast, but the devastation was still immense. Approximately 40,000 people were killed instantly, with total deaths rising to over 70,000 in the following months. The combined impact of the bombings and the Soviet Union's declaration of war against Japan the same day ultimately compelled the Japanese government to surrender on August 15, 1945, effectively ending World War II.

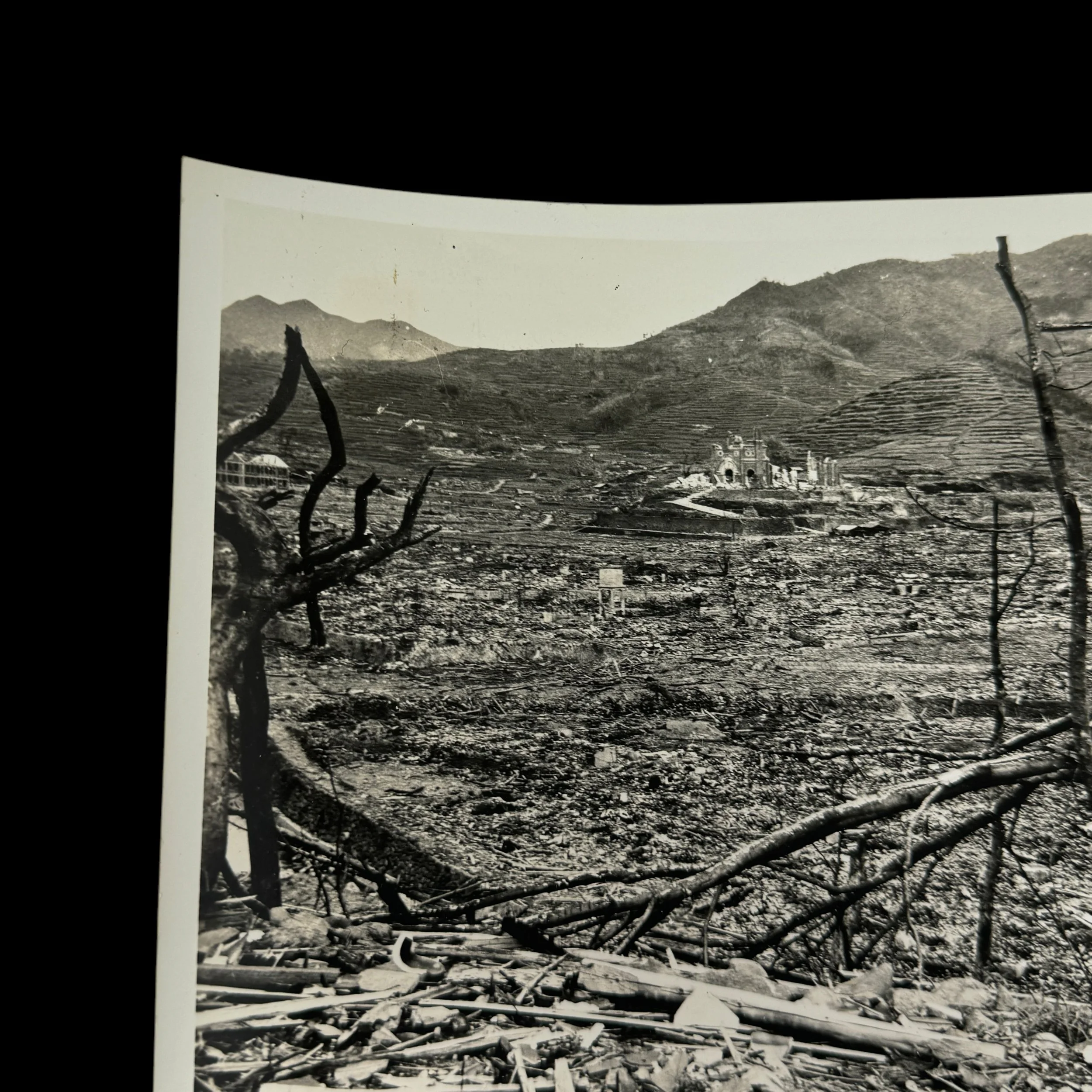

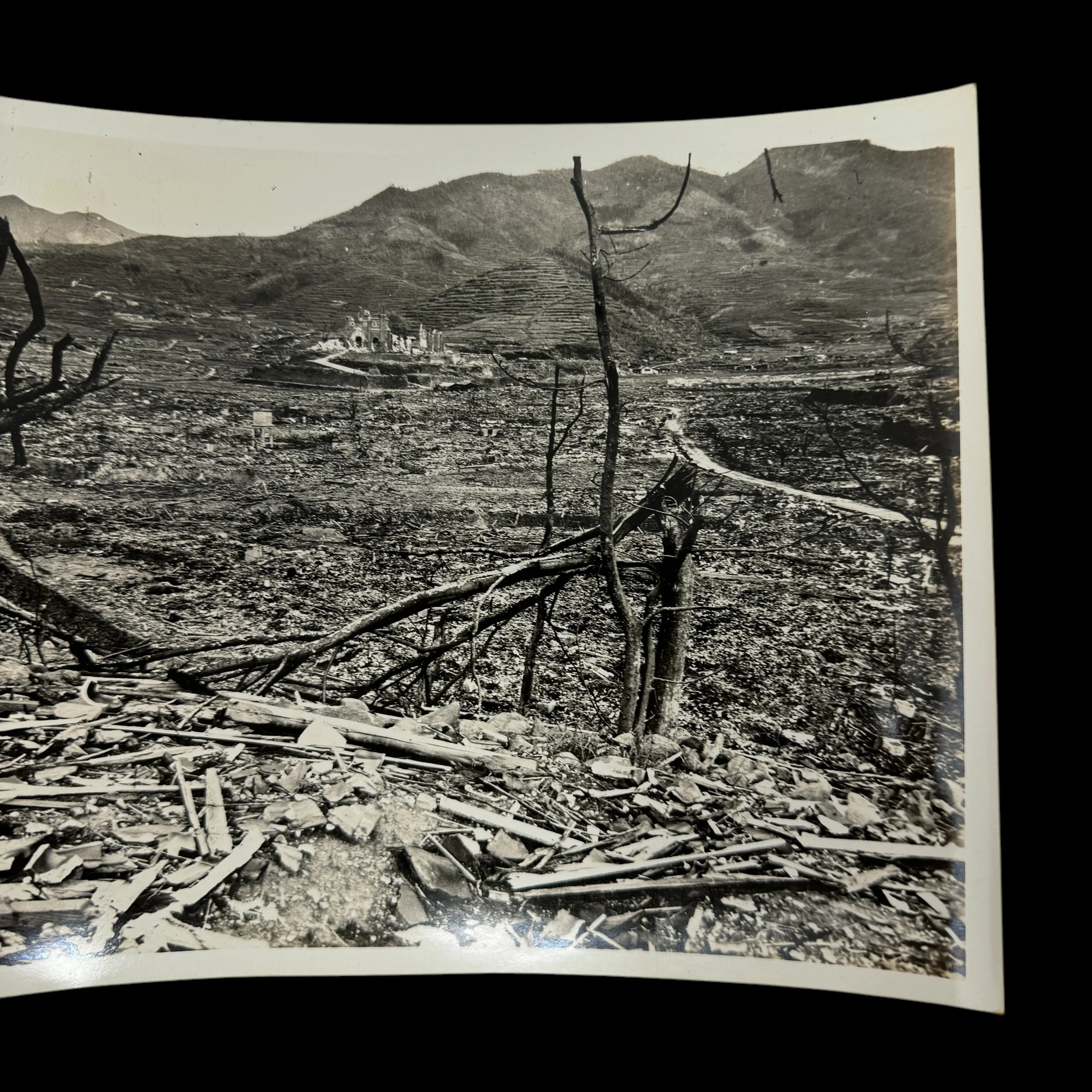

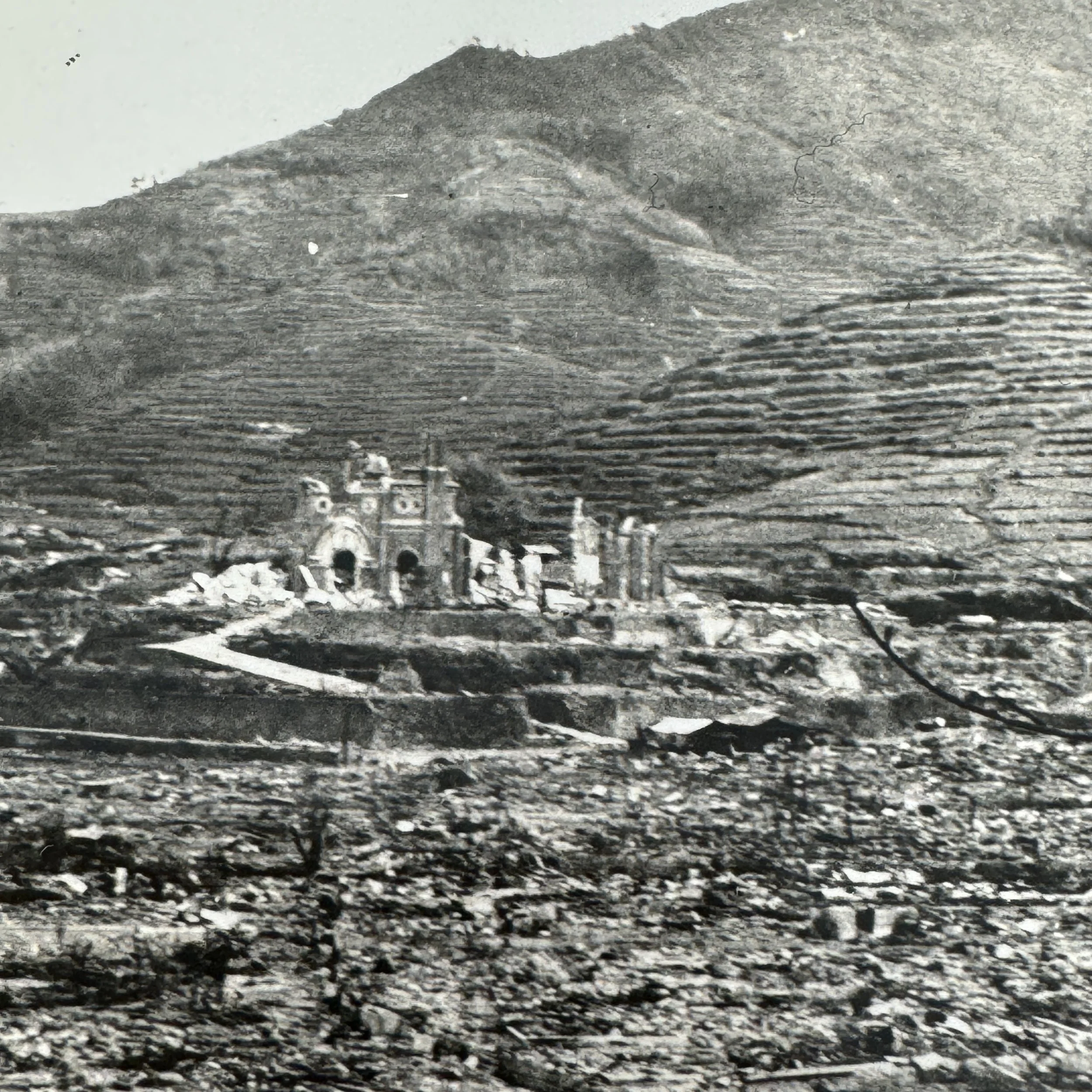

The bombing of Nagasaki, in particular, is often overshadowed by the earlier destruction of Hiroshima, yet it holds a significant place in the narrative of nuclear warfare. The Fat Man bomb was more powerful than Little Boy, utilizing an implosion-type design with plutonium-239. It detonated over the Urakami Valley, where a substantial Christian population lived, including the historic Urakami Cathedral, which was obliterated. The topographical layout of Nagasaki’s hills contained some of the explosion, preventing even greater destruction, but the immediate and long-term impact was harrowing. The city’s industrial infrastructure—shipyards, arms factories, and steelworks—were leveled, while tens of thousands of civilians, including women and children, perished. Unlike Hiroshima, where the bomb exploded in flatter terrain, Nagasaki's hills led to complex damage patterns, with shockwaves funneled through valleys and bouncing off slopes, causing localized but intense destruction.

Photographic documentation played a vital role in understanding and disseminating the consequences of the atomic bombings, especially in Nagasaki. The U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), which conducted the bombings under the command of General Carl Spaatz and the operational guidance of General Curtis LeMay, took extensive aerial and ground photographs of the cities both during and after the bombings. Reconnaissance planes accompanying the Enola Gay and Bockscar, the bombers that carried out the Hiroshima and Nagasaki missions respectively, captured striking black-and-white images of mushroom clouds rising thousands of feet into the sky. These images became some of the most iconic visual representations of nuclear warfare. Aerial photographs taken in the immediate aftermath documented the obliteration from above—grids of urban structures reduced to ash and rubble, bridges destroyed, and urban centers turned into desolate landscapes.

Ground photographs taken by the USAAF and later by members of the Strategic Bombing Survey, which included military personnel, scientists, and photographers, further documented the aftermath. In Nagasaki, these images included panoramic cityscape views of complete devastation, melted steel beams, and shadows of people etched into concrete by the intense heat. Many of these photos were used for military analysis to assess the bomb’s effectiveness, gauge the blast radius, and study structural damage. Scientists used them to understand the behavior of nuclear explosions in urban environments, while military strategists reviewed them to inform future targeting and weapon development strategies. These photographs were also used in governmental and diplomatic briefings to justify the use of atomic bombs and to underscore their power as a deterrent.

Beyond their military application, these images eventually served a broader educational and political purpose. In the postwar years, select photographs were declassified and released to the public, appearing in newspapers, newsreels, and later, history books. They provided an unflinching view of the scale of destruction and human suffering, shaping public discourse about nuclear weapons. In some cases, however, the U.S. government censored more graphic imagery to maintain public morale and control the narrative around the bombings. It wasn’t until decades later that more complete photographic archives were made available, allowing historians and the public to more fully understand the extent of the bombings’ human cost. The photographs of Nagasaki—both from the air and the ground—have since become vital primary sources in the historical record, offering evidence not only of the bomb’s destructive power but also of its ethical and humanitarian implications.

In conclusion, the Manhattan Project was a groundbreaking yet controversial turning point in modern history, culminating in the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While both cities endured unimaginable suffering, the bombing of Nagasaki, with its unique terrain and immense industrial significance, remains particularly complex in both its physical effects and historical interpretation. The photographs taken by the U.S. Army Air Forces—immediate aerial shots of the mushroom clouds and post-blast ground images—played a crucial role in assessing the damage, understanding nuclear weapons, and ultimately shaping both military policy and public perception of atomic warfare. These haunting images remain powerful reminders of the destructive capacity of human innovation and the profound consequences of war.