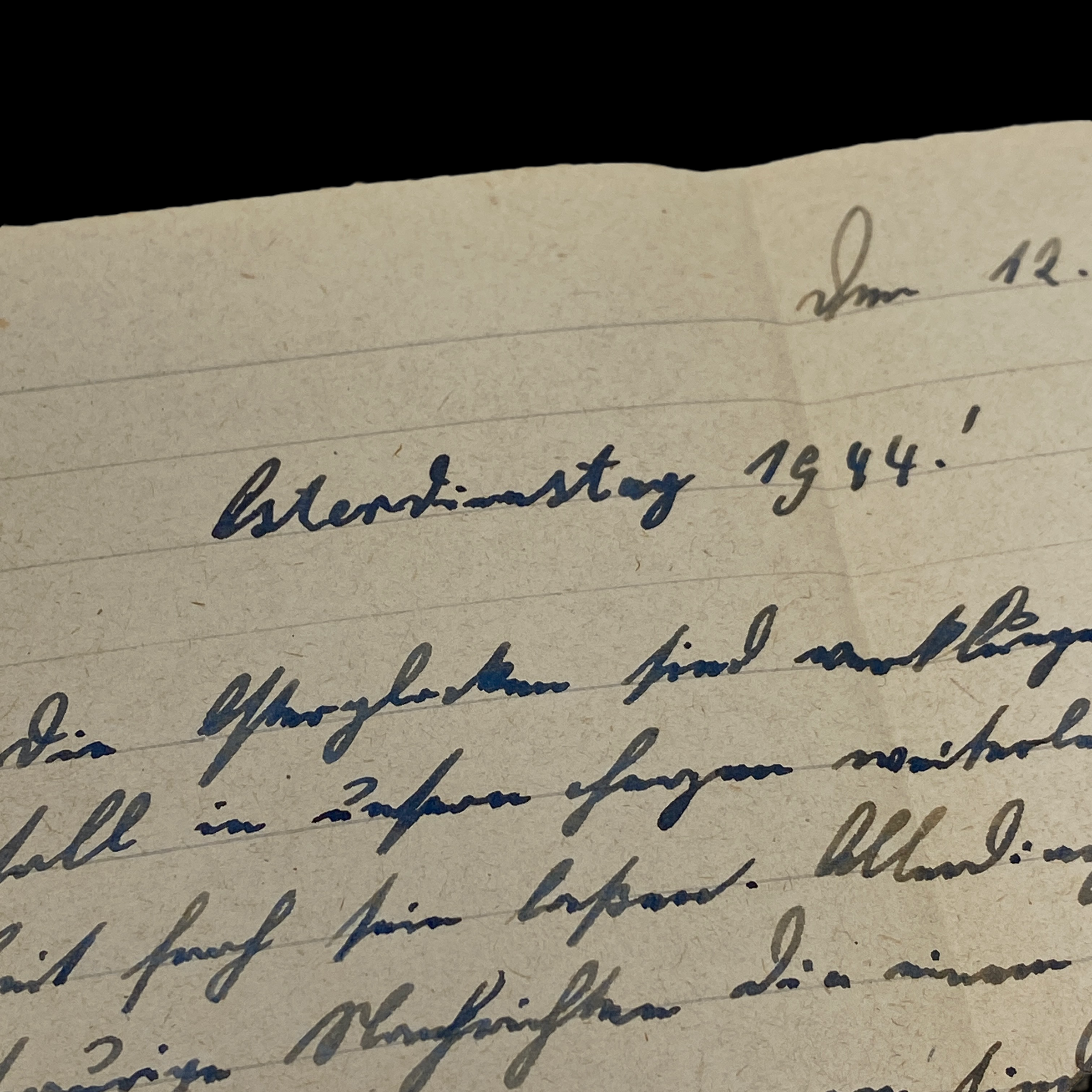

WWII April 1944 German Soldier's Letter from Cherbourg France (2 Months Before Normandy D-Day Landings)

WWII April 1944 German Soldier's Letter from Cherbourg France (2 Months Before Normandy D-Day Landings)

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

This incredible WWII 1944 dated letter was written by a German soldier stationed at the vital port of Cherbourg along the Normandy coast. What makes this letter very interesting is that it was written in April 1944, just two short months prior the infamous Allied D-Day beachhead landings on the Normandy coast on in June 1944.

It is unclear whether this specific German soldier remained station at Cherbourg during the Allied D-Day landings or if he was moved closer to the initial beachhead landing spots within those two months. Regardless, this German soldier was one of the first defenders of some of the most intense fighting in the initial stages of the European Theater campaign.

The specific German soldier that wrote this letter has not been identified so it is unclear whether or not he survived, was a prisoner of war, or ultimately was killed in action during the Battle of Normandy.

Cherbourg and the Battle of Normandy:

The battle of Cherbourg (19-30 June 1944) saw the Americans capture the first major port to fall into Allied hands after D-Day, but although Cherbourg fell fairly quickly, the Germans had still managed to almost cripple the port facilities.

When Normandy had been selected as the target for Overlord, the plan was to land supplies over the beaches and using the two Mulberry harbours, but also to capture the port of Cherbourg, which was expected to act as a major supply base. The planners for Overlord believed that the capture of an intact major port was essential if they were to be able to build up their forces faster than the Germans, and Cherbourg was the only such port in the Normandy area. The Germans were also aware of this, and had strongly fortified every major port in the possible invasion areas, in the hope that this would allow them to overwhelm the Allies on the beaches. The task of taking Cherbourg was given more urgency by the great storm that broke out on 19 June and lasted for four days. This storm destroyed the Mulberry harbor on Omaha Beach, and almost stopped the Allied build-up until 23 June.

Since the American beachheads had been secured and connected by the capture of Carentan, their next main target was Cherbourg. The plan was to push west across the Cotentin peninsula, then turn north towards Cherbourg. At first progress was slow, as the Americans had to fight their way through the strong German defenses in the east of the peninsula. However when they began to push west from their bridgehead across the Merderet, in the center of the peninsula, they shattered the resistance of the only German division in the area. Hitler’s refusal to allow troops to be moved from the defensive lines north of Utah Beach to fill the gap meant that the Americans reached the west coast on 18 June, after an unexpectedly rapid attack.

Cherbourg was protected by a ring of defences on the land side (the Cherbourg Landfront), built into three ridges that led to the port, as well as a number of forts around the city itself (including the formidable Arsenal). The land defences were between 4-6 miles from the port, and were well positioned on commanding ground. They covered all of the best lines of approach, and took advantage of natural features to create anti-tank barriers. The infantry was supported by anti-aircraft batteries deployed in positions where they could also act attack surface targets.

The defences were manned by the equivalent of four infantry regiments, formed from a mix of those units that had been able to retreat to Cherbourg after the fighting further south in the Cotentin, the actual garrison of the port and the many other troops caught up in the disaster. On the German right (in the west) was Kampfgruppen Mueller, made up of the survivors of the 243rd Division, and the 922nd Regiment. In the south-west was Kampfgruppen Keil, built around the 919th Regiment. In the south-east was Kampfgruppen Koehn, with the 739th Regiment. Finally on the German left (in the east) was Kampfgruppe Rohrbach, built around the 729th Regiment.

The defence was commanded by General Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben. He had fought on the Eastern Front, before being given command of the 709th Static Infantry Division in 1943.He estimated that he had about 21,000 men to defend the Port, but lacked officers. One fifth of his troops were Poles or Russians.

The defence of the city might have lasted for long if Hitler had allowed the troops fighting in the Cotentin to retreat north earlier. Instead he insisted on an attempt to defend a line further south, which ended in the destruction of most of the troops involved. Some survivors from the 77th and 243rd Divisions made it into Cherbourg, but von Schlieben believed that they were more of a ‘burden than a support’. Having forced Schlieben into an unwinnable defence, Hitler sent the obligatory encouraging message, insisting that it was his ‘duty to defend the last bunker and leave to the enemy not a harbour, but a field of ruins.’

Advance to Cherbourg:

The leading American troops reached the west coast of the Cotentin on 18 June. The newly activated 8th Corps was given the task of protecting the southern flank of the US position, while General Collins’s 7th Corps was ordered to push north. This would be an easier task than expected. The Germans still had an intact defensive line on the eastern part of the peninsula, but it ended about half way across, so the westernmost American troops would be advancing through almost undefended country.

On 19 June the 4th, 9th and 79th Divisions carried out a reconnaissance in force. The rapid push to the west coast had actually carved a hole in the German lines on the Cotentin, and General Schlieben was well aware that any attempt to make a stand in the east, where his lines were more intact, could only end with complete destruction of those troops as they were outflanked from the west. As a result that evening the Germans abandoned their last major positions south of the city, at Valognes (ten miles to the south of Cherbourg) and Montebourg, four miles further to the east, and withdrew into the fortifications. At the end of the day the US 9th Division, on the left, had already reached the outer defences of Cherbourg, while the other two divisions had covered about half of the distance.

On the morning of 20 June the Americans thus found the area immediately in front of them generally undefended. On the right the 4th Division occupied Valognes without a fight, and then reached their final objectives, to the south east of Cherbourg, by nightfall. At the end of the day they occupied a line from the Bois de Roudou north east to le Theil. In the centre the 79th Division pushed north to a line that ran from the Bois de Roudou, west to St. Martin-le-Greard. Both divisions then ran into the outer line of defences, and paused for the night.

On the left the 9th Division had more ambitious objectives for 20 June. They were ordered to attack towards Flottemanville-Hague and Octeville, two villages that were between the main port and the German outer defences, and if possible cut the road from Cherbourg to Cap de la Hague, the north-western tip of the peninsula. In theory the second task could have been the easier of the two, as there was a gap between the western side of the fortifications and Cap de le Hague, but the route chosen for the 60th Infantry Regiment cut across the defended area. The first task was given to the 48th and 39th Infantry. The 47th was to follow the 60th Infantry north, then attack east from Vasteville towards the Bois du Mont du Roc, south-west of Cherbourg. The 39th Infantry would support the 47th’s attack, and then attack on its left flank, towards Flottemanville. All went well until noon. The 60th Infantry was then held up by heavy artillery fire just short of its first objective, Hill 170. Enough progress had been made to allow the 47th to attack east, but their advance was quickly stopped by fire from the German defences. The 39th Infantry attack was cancelled, and the 60th was ordered to attack east towards Flottemanville, but this attack also failed.

The Main Siege:

The Americans spent most of 21 June getting ready for the main attack into the city. The 4th Division still had to push forward to reach the German lines, but the other two divisions were able to spend the day preparing for the assault.

On the night of 21 June Collins broadcast a demand that the Germans surrender, but without success.

The main attack began on 22 June. It was preceded by a large scale air attack. First four squadrons of rocket armed Typhoons from the RAF 2nd Tactical Air Force attacked. They were followed by six squadrons of RAF Mustangs, then by twelve groups of fighter-bombers from the US 9th Air Force, followed by all eleven groups from the US 9th Bomber Command. Between them these aircraft dropped around 1,100 tons of bombs.

The plan for 22 June was for the 9th and 79th Divisions to attack into Cherbourg, while the 4th Division blockaded the city from the east. The 9th’s divisions main target was Octeville (to the south-west of the city) while the 79th Division was to advance towards Fort du Roule, to the south of the city. In both cases the Americans ran into stiff resistance, and they made much less progress than expected. The 9th Division ended the day still some way short of Flottemanville and the Bois de Mont du Roc. The 79th Division managed to get past the German strongpoint at les Chevres, but was stopped south of the anti-aircraft position at la Mare a Canards. At this stage in the battle each pillbox had to be blasted out, and Collins' men developed a slow but relatively safe method of dealing with these fortifications. Artillery and dive bombers would force the Germans into their concrete defences. A light bombardment would keep them pinned down while the infantry advanced to within 400 yards of the pillbox. The infantry would then take over, pouring heavy fire into the embrasures, while combat engineers worked their way around to the rear, blew the doors open and then threw explosives or smoke grenades into the pillbox.

On 23 June the Americans pushed into the main German defences. On the left the 9th Division captured the Flottemanville area, and the high ground at the western end of the Bois du Mont du Roc, thus capturing a ridge of high ground between the original Landfronte and the port. In the centre the 79th was still unable to take la Mare a Canards, but were able to outflank the position to the west, ready for a renewed attack on the following day. On the right the 4th Division began to push north-west towards Tourlaville and the high ground south-east of the port.

On 24 June Schlieben reported that he had committed all of his reserves including a number of non-combatants equipped with old French weapons, but that the fall of Cherbourg was inevitable and the only question was how long he could delay it. He also handed out a large number of Iron Crosses that had been dropped in by parachute, in an attempt to boost morale. On the American side the 9th Division pushed on to the north-east, reaching the western edge of Octeville. In the centre the 79th Division finally cleared la Mare a Canards, and got close to Fort du Roule, but German fire from Octeville to the west stopped them getting any further. On the right the 4th Division got close to Tourlaville, which was then evacuated by the Germans, allowing the Americans to occupy the village on the night of 24-25 June.

On 25 June the Allies carried out a massive naval bombardment, using three battleships, four cruisers and a number of destroyers. On land the 9th Division finally captured Octeville, and got into the western suburbs, capturing the German fort at Equcurdreville. They reached the beach west of the city, but then pulled back a short distance for the night.

In the centre the 79th Division began to attack Fort du Roule, which dominated the harbour area. This was a two level fortress, built into a rocky outcropping overlooking the city, with the coastal guns in the lower level. The upper level contained the land side defences. By the end of 25 June the Americans had captured the upper level of the fort, but the lower level was still in German hands.

On the right the 4th Division captured a German coastal battery to the north of Tourlaville, and was then given permission to push west into Cherbourg. They were able to occupy the eastern streets fairly easily, but it took until the following morning for German pillboxes on the coast east of Fort des Flamands (at the eastern end of the inner harbour) to be cleared.

By now Schlieben knew that the battle was lost, and actually asked Hitler for permission to surrender. Unsurprisingly this was refused.

The crucial breakthroughs came on 26 June. At 11.00am the 22nd Infantry Regiment (4th Infantry Division) attacked Maupertus airfield, to the east of the city. The airfield fell after a day long battle. The 22nd then moved north to take Batterie Hamburg on the coast east of Cherbourg, capturing 990 men and four 240mm guns. Elsewhere the 79th Division completed the capture of Fort du Roule, taking the lower levels. This allowed other troops to move into the centre of the port without coming under fire from its guns.

Schlieben himself surrendered on 26 June, after destroying his papers and codes. He was captured in an underground shelter at St Sauveur, just to the south-west of the main city, with 800 men. The General had been trapped in the tunnels since the previous day, when his command post had come under heavy artillery fire. Although he surrendered in person, he refused to order a general surrender of the garrison, although another 400 Germans surrendered at the city hall after they discovered he had capitulated.

The arsenal, in the north-west of the city, was still in German hands. The Americans were preparing for a massive attack on 27 June but luckily a psychological warfare unit was able to convince the defenders to surrender. This force was 400 strong, and was commanded by Generalmajor Robert Sattler, deputy commander of the fortress. When Collins sent his Psychological Warfare Unit to the Arsenal, Sattler indicated that he would surrender if the American tanks would fire a few shells at the fortress. The shells were duly fired, after which Sattler and 400 men marched out with their bags packed!

The Germans still held some of the harbour forts, but they surrendered on 29 June after coming under attack from tank destroyers and dive bombers.

There was some British involvement in the attack. The most significant was the use of British warships to support the main attack. Less well known is the mission given to Royal Navy Commando 30 Assault Unit, which was given the task of capturing the Kriegsmarine’s naval intelligence HQ in the Octeville suburb to the south-wets of Cherbourg.

The fall of Cherbourg didn’t quite end the Cotentin campaign. Around 6,000 Germans still held out in the north-western corner, the Cap de la Hague, but they too surrendered on the final day of June.

Although the city didn’t hold out for as long as Hitler had hoped, the German defence lasted long enough for Konteradmiral Wilhelm Hennecke to carry out the planned demolition of the port facilities, starting on 7 June. This was acknowledged by Colonel Alvin G. Viney, the American engineer who wrote the plan to restore the port, as ‘the most complete, intensive and best-planned demolition in history’. The outer breakwater had been cratered, the quay walls damaged, essential cranes destroyed, the harbour blocked with sunken ships and hundreds of mines scattered across the harbour. Teams of British engineers spent weeks painstakingly deactivating these mines, while American engineers cleared the physical damage, and the first deep-draught cargo ships were able to enter the outer harbour on 16 July, but it was months before anything like the expected amount of supplies could travel through Cherbourg. It took until mid August for the Allies to clear the port. On 12 August the US Army Transportation ship S160 was able to dock, unloading a mixed cargo of steam and diesel locomotives. However the port wasn’t able to operate at close to its full capacity until the autumn. Luckily it turned out to be possible to move vast amounts of supplies across the Normandy beaches, through the British Mulberry harbour, and using the smaller ports that fell into their hands almost intact.