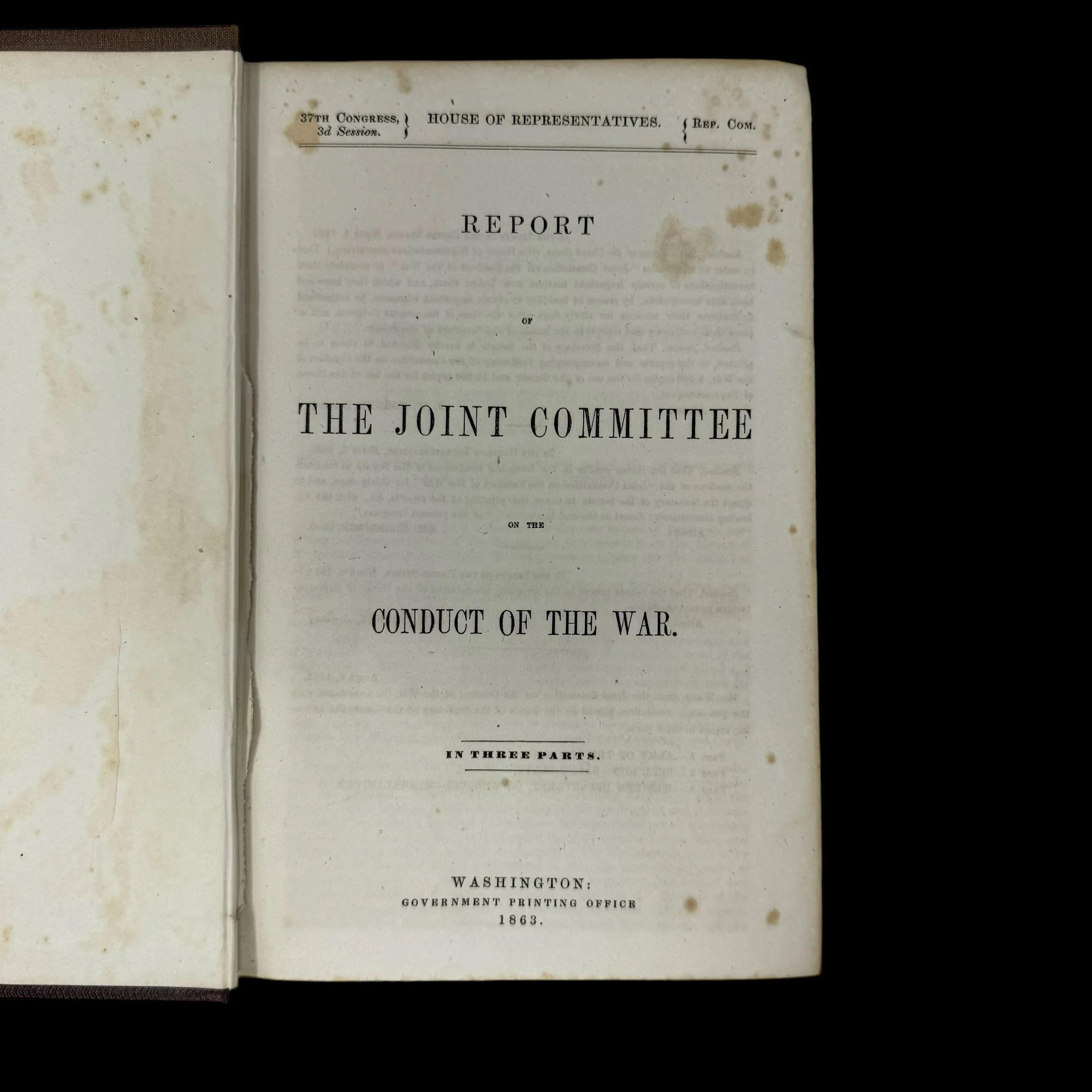

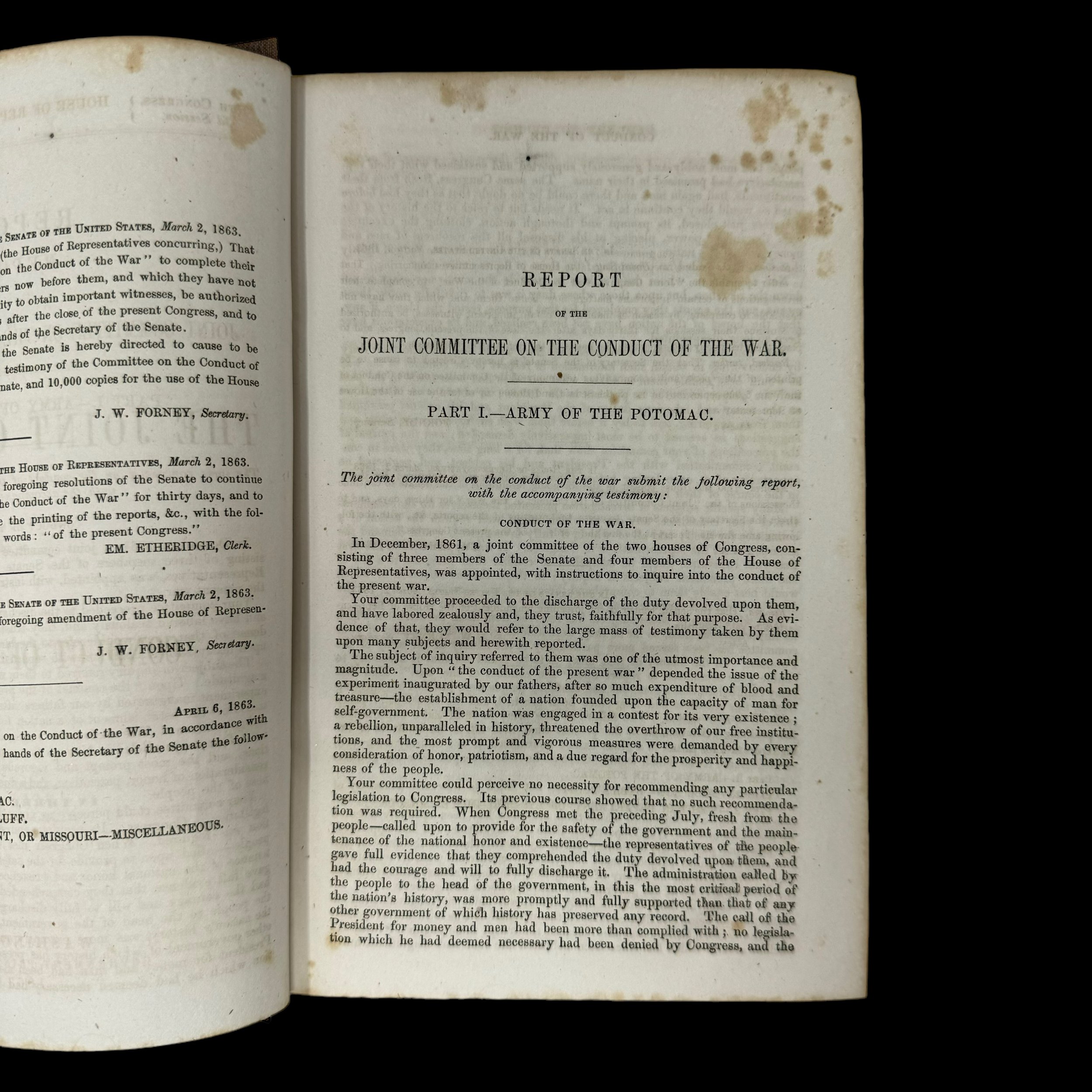

EXTREMELY RARE! 1863 Civil War Report - House of Representatives 37th Congress - SECRET Joint Committee "Conduct of the War"

EXTREMELY RARE! 1863 Civil War Report - House of Representatives 37th Congress - SECRET Joint Committee "Conduct of the War"

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

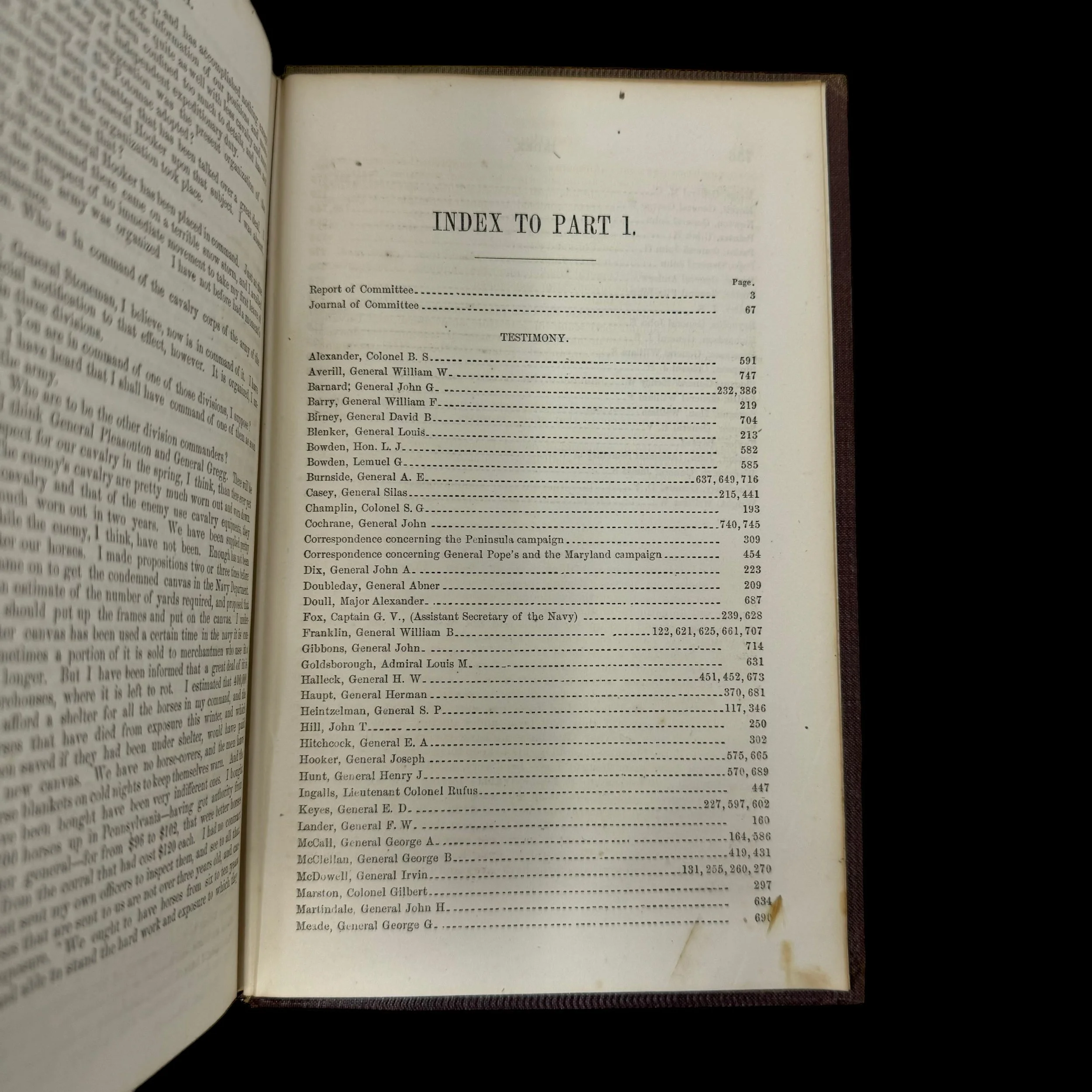

Page Total: 756

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was a United States congressional committee started on December 9, 1861, and was dismissed in May 1865. The committee investigated the progress of the American Civil War against the Confederacy. Meetings were held in secret, but reports were issued from time to time.

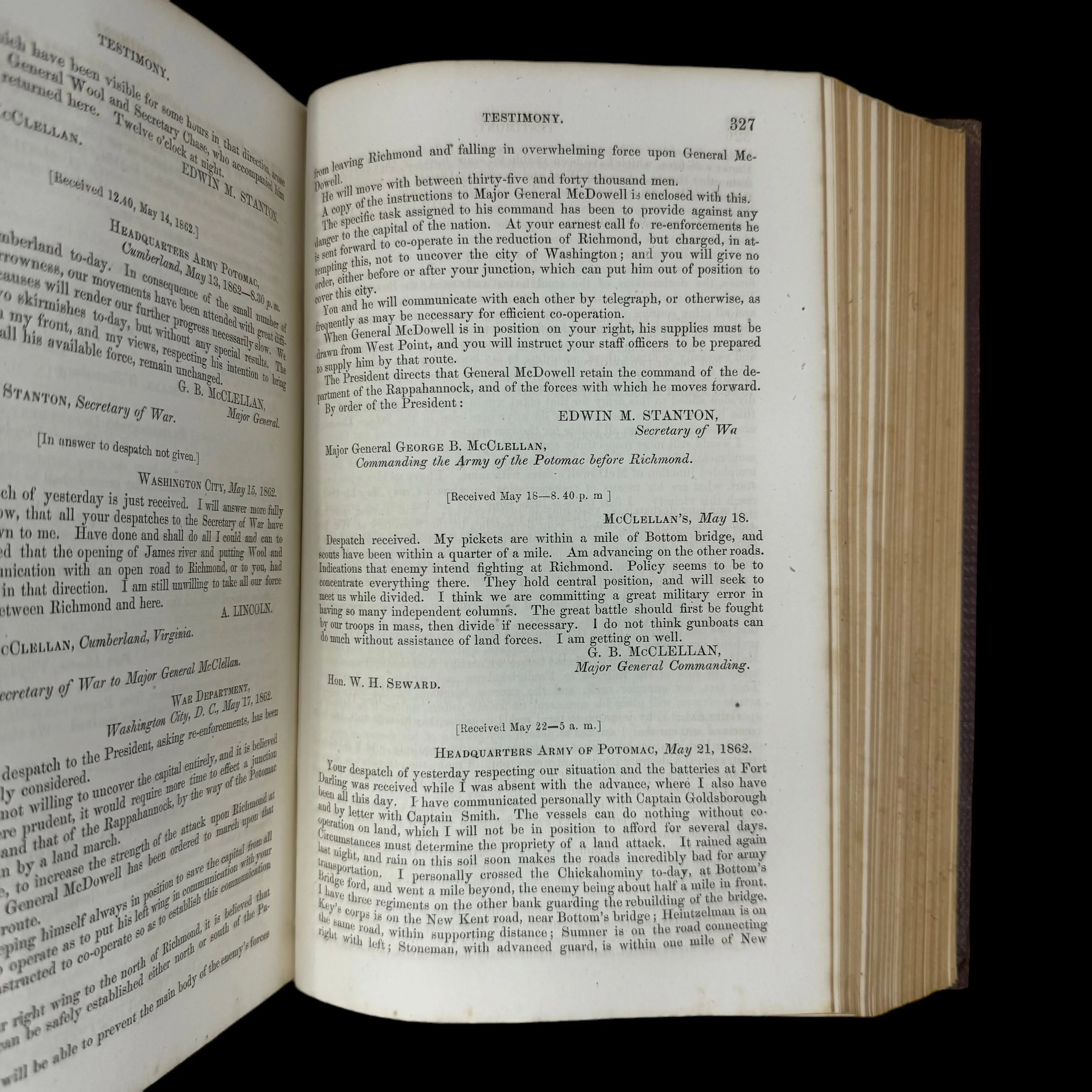

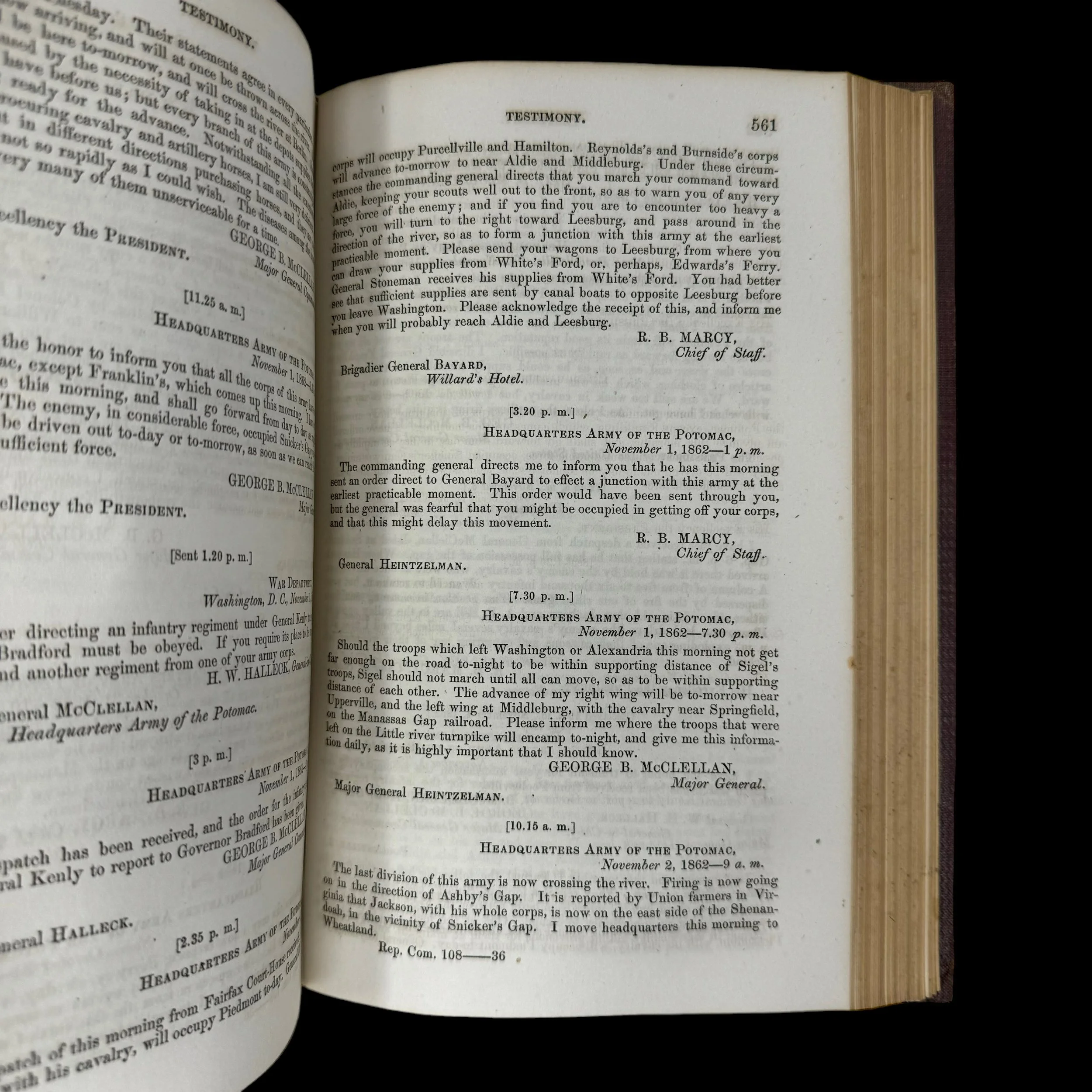

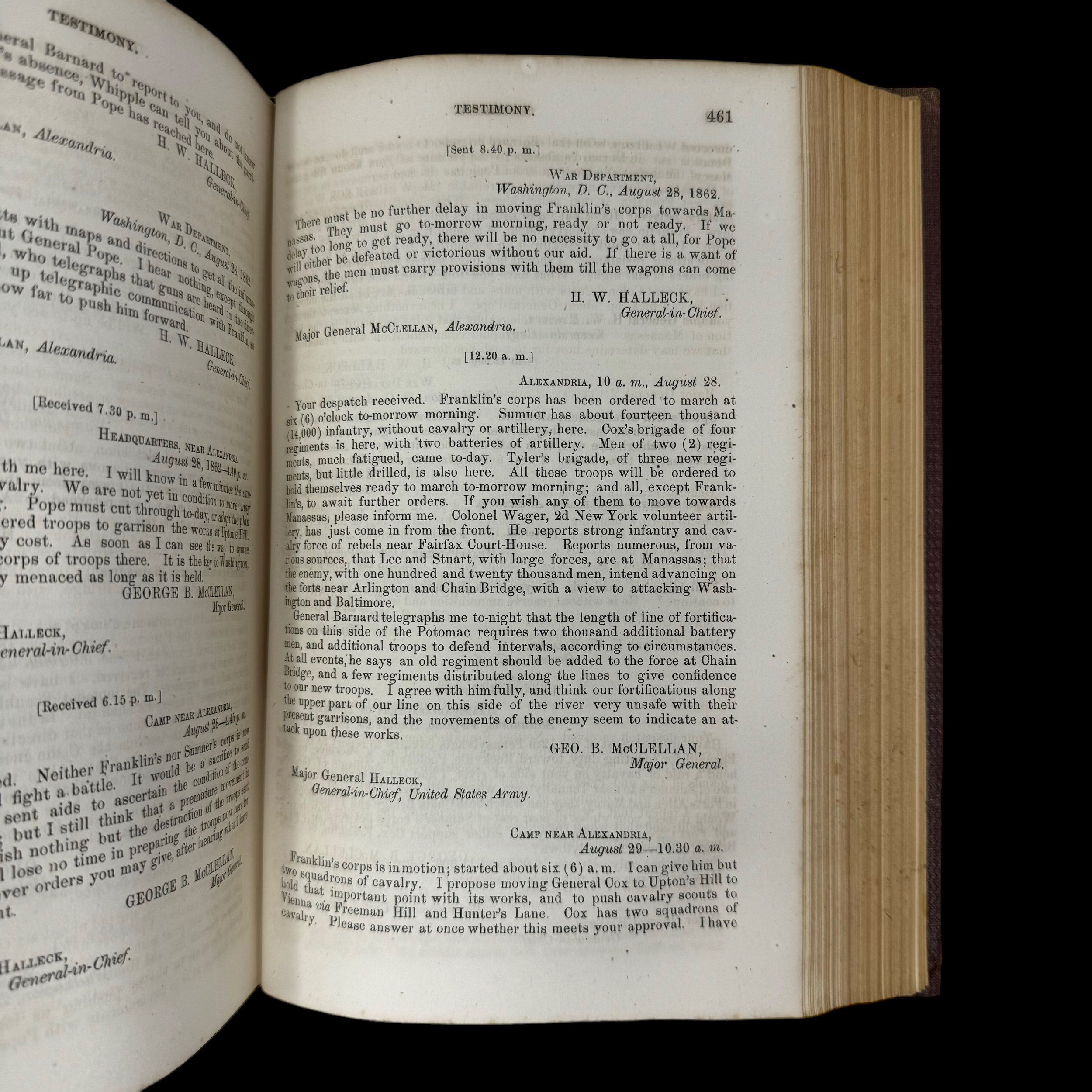

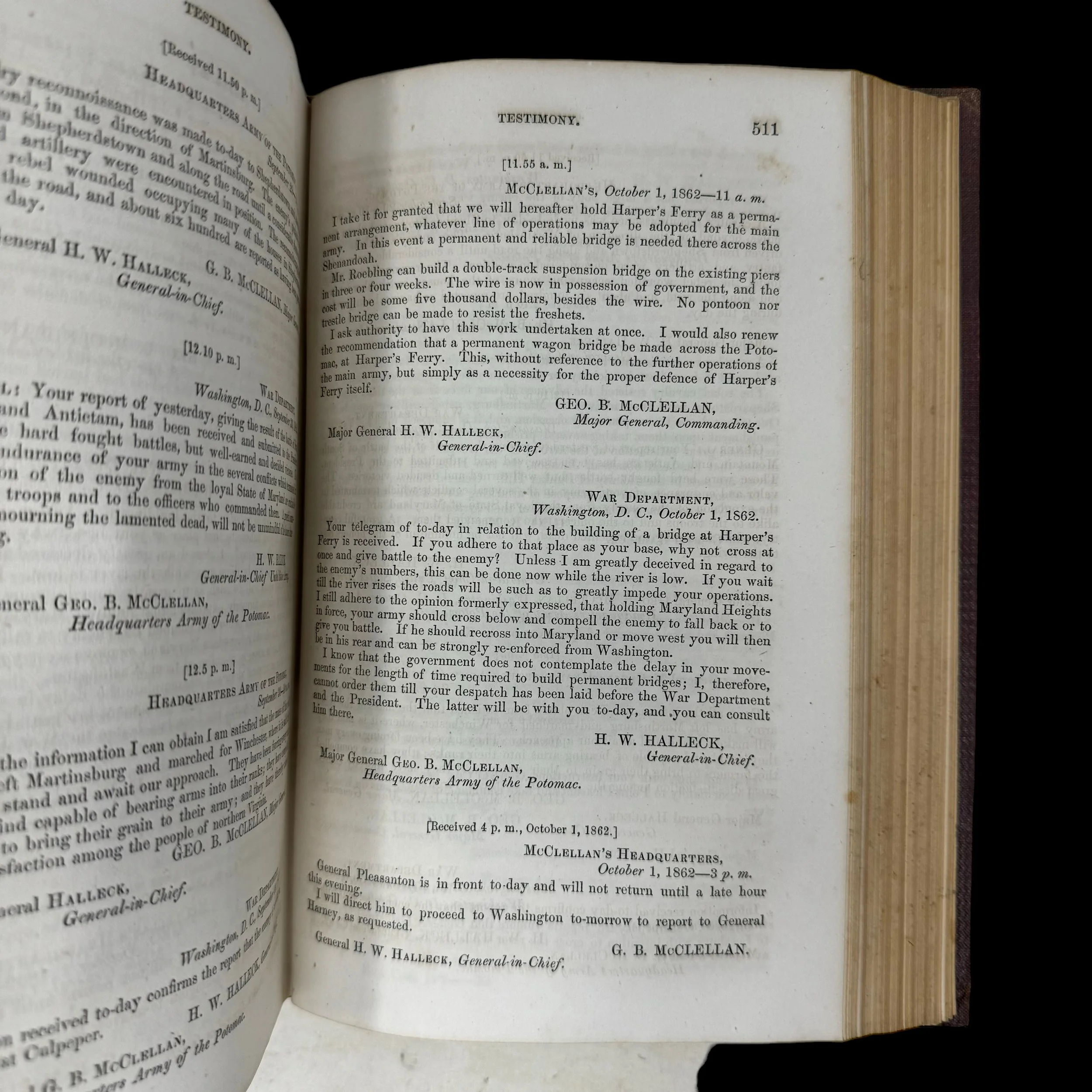

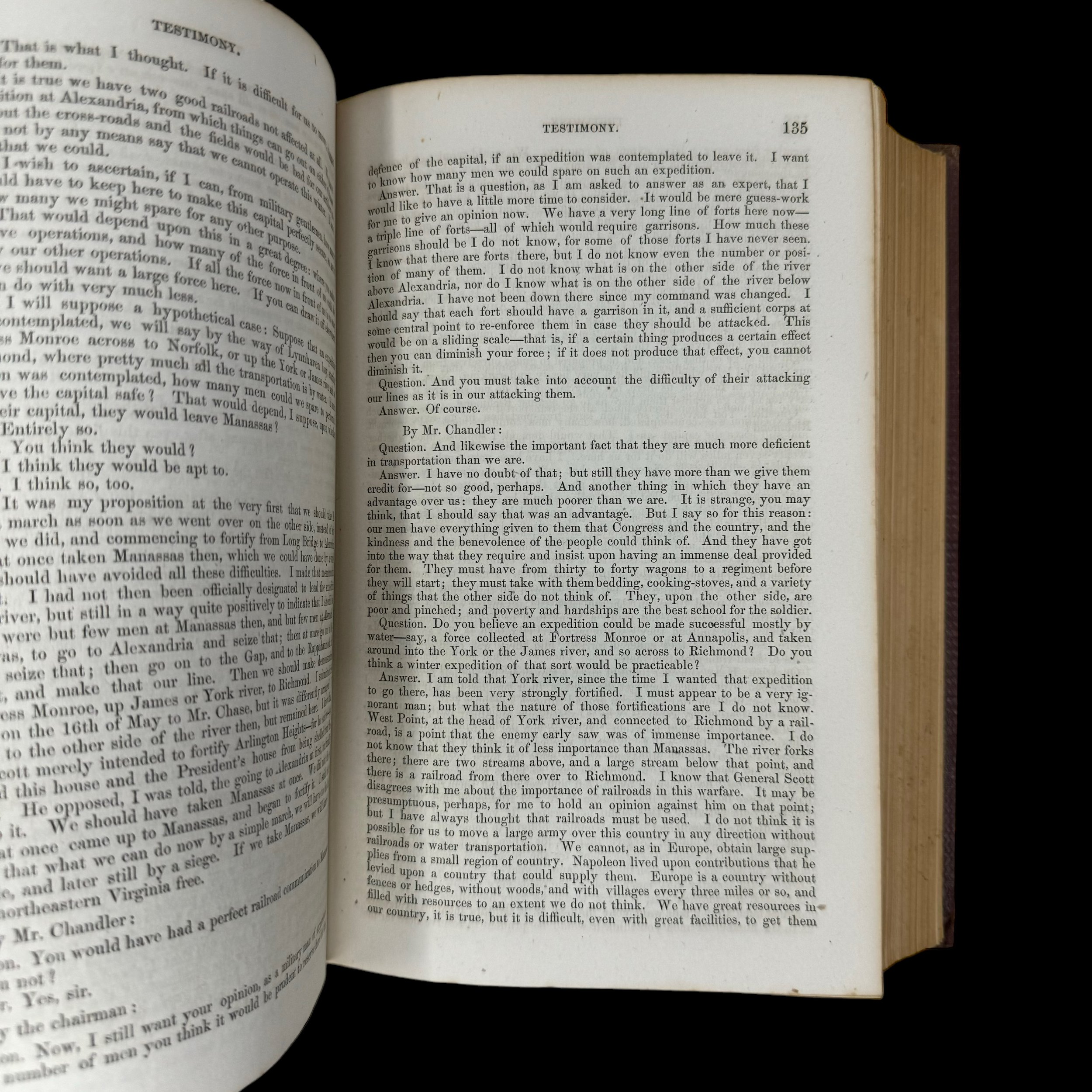

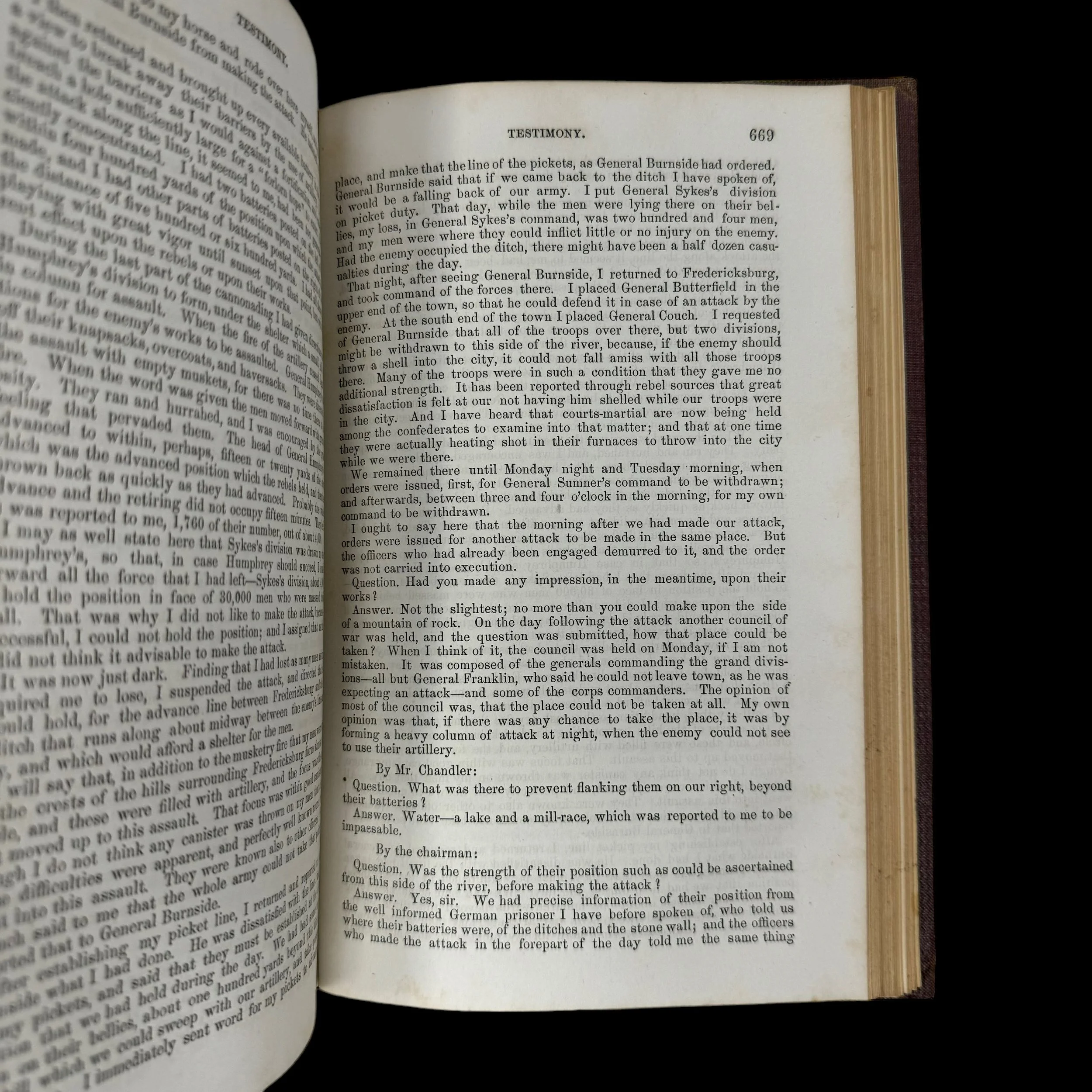

It's extremely rare and museum-grade Civil War report was printed by the Washington Government Printing Office in 1863 during the American Civil War. This extremely rare congressional report was printed for the “House of Representatives” as the 37th Congress 3rd session. This special “Joint Committee” held 272 meetings and received testimony, in Washington and other locations, often from military officers. Though the committee met and held hearings in secrecy, the testimony and its related exhibits were published at irregular intervals in the numerous committee reports of its investigations.

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was a United States Congressional investigating committee created to handle issues surrounding the American Civil War. It was established on December 9, 1861, following the Union defeat at the Battle of Ball's Bluff, at the instigation of Senator Zachariah T. Chandler. The committee continued until May 1865. Its purpose was to investigate such matters as illicit trade with the Confederate States, medical treatment of wounded soldiers, military contracts, and the causes of Union battle losses. The committee was also involved in supporting the war effort through various means, including endorsing emancipation of slaves, the use of black soldiers, and the appointment of generals known to be aggressive fighters. Chairman Benjamin Wade and key leaders were Radical Republicans, who wanted more aggressive war policies than those of Lincoln.

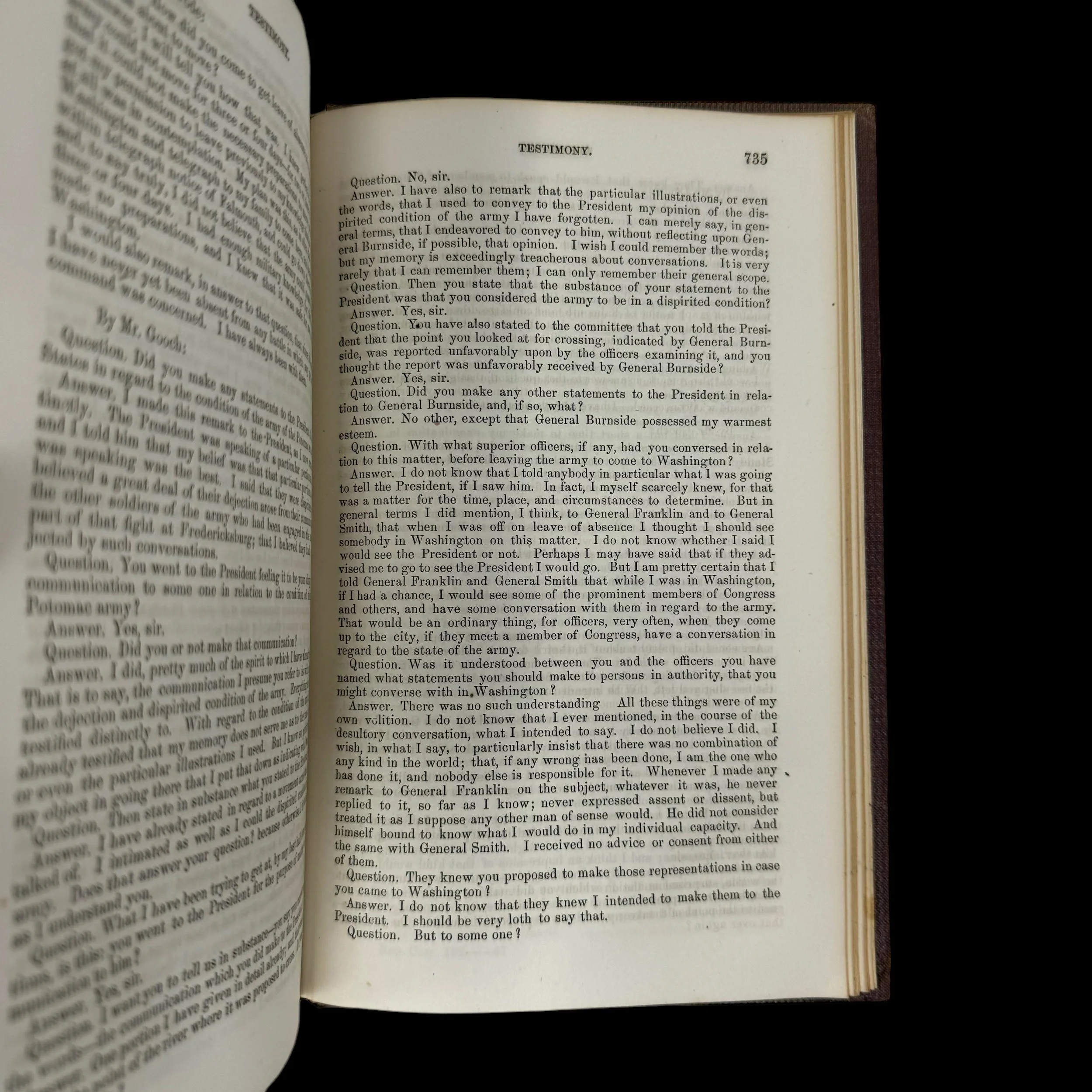

Union officers often found themselves in an uncomfortable position before the committee. Since it was a civil war, pitting neighbor against neighbor, the loyalty of a soldier to the Union was simple to question. Also, since Union forces had performed mostly badly against their Confederate counterparts early in the war, particularly in the Eastern Theater battles that held the attention of the newspapers and Washington politicians, an officer could easily be accused of being a traitor after he lost a battle or was slow to engage or pursue the enemy. The politically charged atmosphere was very difficult and distracting for career military officers. Officers who were not known Republicans felt the most pressure before the committee.

The committee held 272 meetings and received testimony, in Washington and other locations, often from military officers. Though the committee met and held hearings in secrecy, the testimony and its related exhibits were published at irregular intervals in the numerous committee reports of its investigations. The records include the original manuscripts of certain postwar reports that the committee received from general officers. There are also transcripts of testimony and accounting records regarding the military administration of Alexandria, Virginia.

One of the most colorful series of committee hearings followed the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, when Union Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles, a former Representative, accused Maj. Gen. George G. Meade of mismanaging the battle, planning to retreat from Gettysburg before his victory there, and failing to pursue and defeat Robert E. Lee's army as it retreated. It was mostly a self-serving effort on the part of Sickles, who was trying to deflect criticism from his own disastrous role in the battle. Bill Hyde notes that the committee's report on Gettysburg was edited by Wade in ways that were unfavorable to Meade, and the evidence was even distorted. The report was "a powerful propaganda weapon" (p. 381), but the committee's power had waned by the time that the final testimony, that of William T. Sherman, was taken on May 22, 1865.