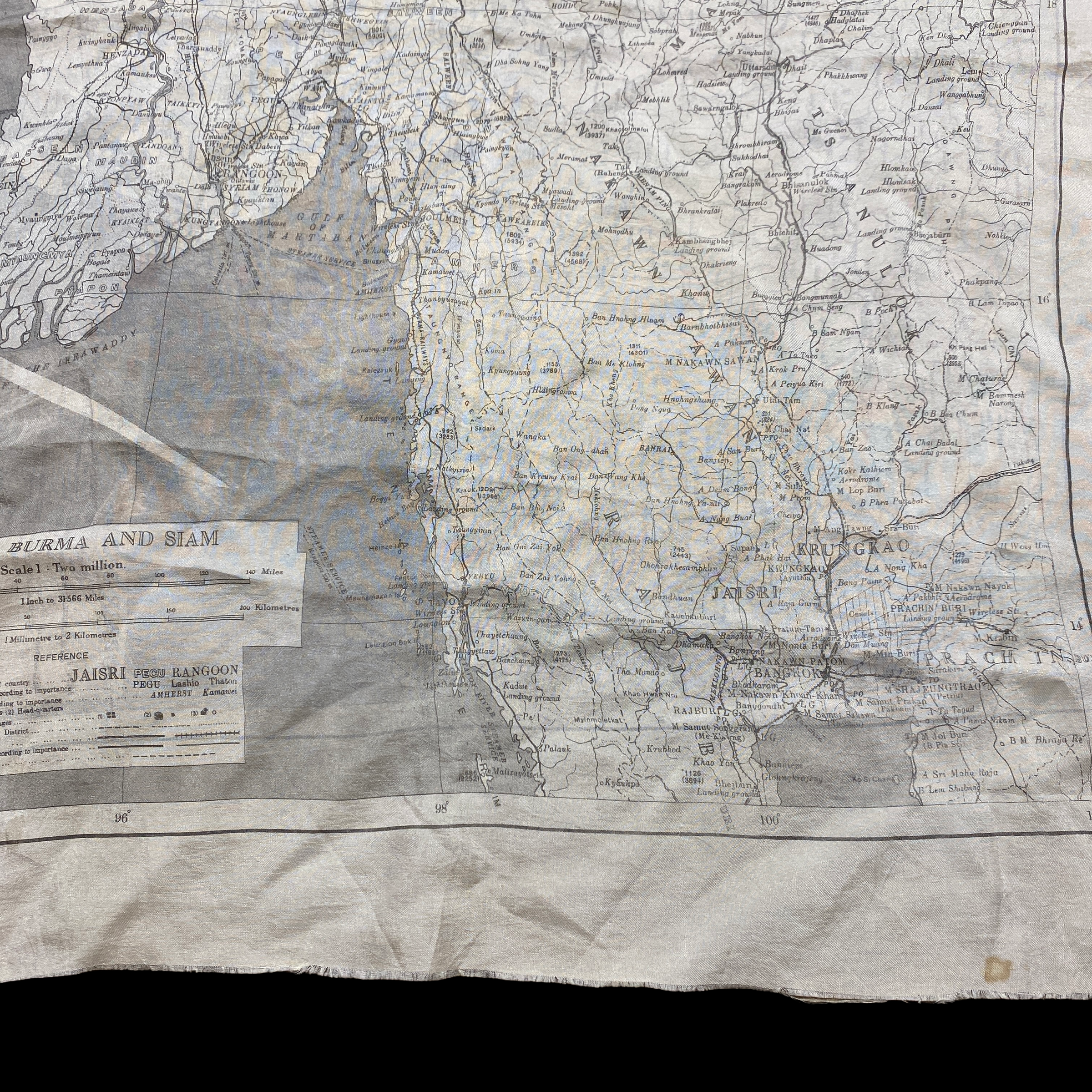

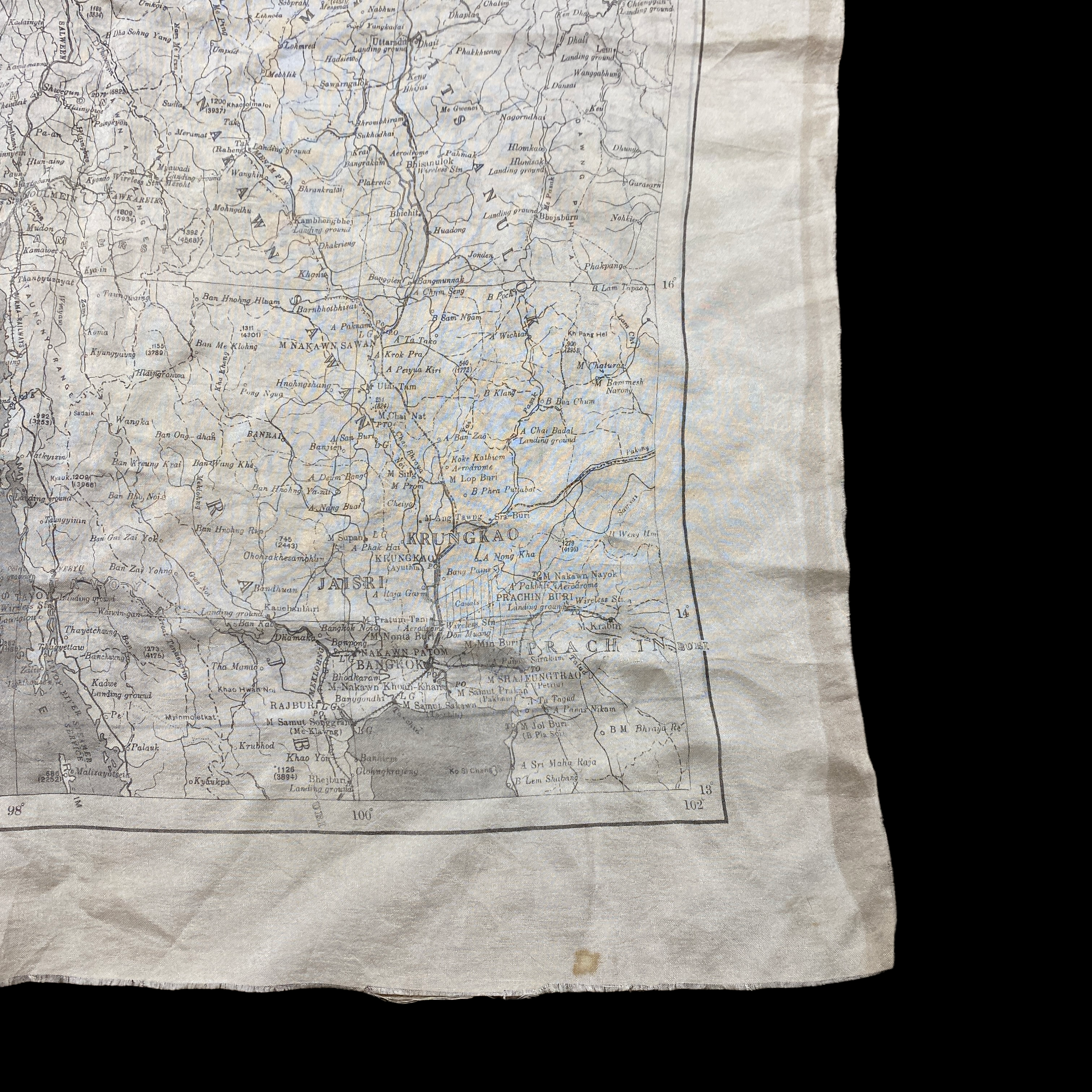

WWII Burma Campaign British American Pilot Bailout Silk Survival Map Pacific Theater

WWII Burma Campaign British American Pilot Bailout Silk Survival Map Pacific Theater

Comes with hand-signed C.O.A.

This incredible and museum-grade WWII double sided pilot’s bail out silk map is shows “LOWERE BURMA” and “UPPER BURMA”. This large Pacific Theater pilot bailout survival map was used during the Burma Campaign during WWII against Japanese forces. This very delicate silk cloth chart does show signs of theater use and would have been carried by British and American pilots participating in the Burma Campaign.

These cloth charts were worn as neck scarves or stuffed in the pant/jacket pockets by pilots during WWII as part of their survival gear. During WWII these silk bailout maps were produced in varying quantities by the Allied forces on thin silk (waterproof) material. The idea was that if an Allied pilot’s plane was shot down behind enemy lines they should have a map to help him find his way to safety if he escaped or evade capture.

WINGS OVER BURMA - Air Support in the Burma Campaign:

AC-47 careens through a narrow jungle-covered valley bordered by towering mountains. The crew finally spots the ground signal, and after determining that the drop zone (DZ) is correct, the “kickers” push the cargo out the door. First, bags of rice free fall to the ground. As they land with a thud, the airplane circles for another pass. Ammunition and other supplies float to earth under multi-colored parachutes. The airplane then makes a beeline for home, keeping low to the ground while the crew watches for Japanese fighters. This was a daily event in north Burma during WWII. The following article gives a brief overview of how aerial resupply overcame the logistical difficulties of north Burma operations, and then explains how it was utilized by a specific unit, the paramilitary Detachment 101 of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). It is relevant today because the pioneering efforts in the skies over north Burma influenced how aerial resupply would be done in numerous post-WWII conflicts.

The rugged, trackless, jungle-covered terrain that dominated north Burma made aerial resupply necessary. The lack of roads made it the best solution to meet the American-led Northern Combat Area Command’s (NCAC) logistics requirements. This was despite the Japanese air threat, which was significantly reduced when NCAC forces captured the Myitkyina airfield on 17 May 1944.1 North Burma was the one major American operational theater where aerial resupply to non-airborne ground forces was a routine practice. Cargo was delivered by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) in three ways; by landing and unloading an airplane at an airstrip; by free-dropping supplies; or by parachuting cargo bundles. By 1945, the ability to conduct aerial resupply in north Burma was so well-developed that the USAAF drop squadrons sustained five Chinese and one British division, the MARS Task Force, numerous service troops, and 10,000 OSS-led guerrillas.

The USAAF accomplished this difficult task by applying modern industrial assembly-line principles. Drop crews simply could not customize each supply run. Instead, most drops consisted of standard packaged loads based on the number and type of troops. Differing food items for each of the multi-ethnic Allied groups fighting in north Burma required separate rations for each. For instance, Hindu troops would not eat beef, Muslim troops would not eat pork, Chinese troops required large amounts of rice, and American troops ate pre-packaged rations. Regardless of the nationality or ethnic group they were intended for each ration had basic components. They were nutritionally balanced and had the equivalent of a grain, a vegetable or fruit, and a meat or protein. These ration loads were loaded separately into the drop aircraft depending on the receiving unit and in the order that they went out of the airplane.3 Free-dropped items were loaded last so they could be dropped first and not foul parachute dropped supplies.

Aircraft were loaded overnight so they could take off early the next day, drop their load, and return to conduct a second supply mission if time allowed. Not only did this enable more supplies to get into the field, but it also maximized the use of scarce drop aircraft. First Lieutenant (1LT) Bernard M. Brophy, serving with OSS Detachment 101, recalled the grueling schedule. To load the aircraft he said, “we would be down at the airstrip at about four or five o’clock in the morning.” By the time that they returned he said, “you could be out fifteen hours a day.”4 While the aircraft were loaded, ground crews performed maintenance checks and refueled them. Around the clock operations were necessary. The number of troops requiring support, the limited number of cargo aircraft, and the unpredictable weather—especially during the monsoon season—dictated that supplies reach the field whenever possible.

Corporal George W. Patrick of the 475th Infantry Regiment of the MARS Task Force, recalled that they received air drops every three days.5 But, the efficiency of the USAAF made aerial resupply look easier from the ground than it was. Getting the supplies out to the field on time was even more crucial because most drop planes flew by day. Although done occasionally, the cargo aircraft did not have the navigational systems necessary for low-level night flights in the uncharted mountains.

The main resupply aircraft was the venerable Douglas C-47 Skytrain. Developed as the pre-war DC-3 airliner, the C-47 became the U.S. Army’s major troop carrier in WWII and remained in service long after the war. The aircraft was so well-engineered and robustly built that numerous DC-3/C-47 airplanes are still commercially operated or serving foreign militaries almost seventy-five years after the first model was flown. The other major cargo aircraft was the Curtiss C-46 Commando. Originally designed to replace the C-47, it was rushed into wartime production. The airplane had numerous design flaws and was not as stable as the C-47. Although the C-46 could carry nearly twice the payload of a C-47 (6,000-7,000 pounds) pilots much preferred the latter.6 For special missions, the small, fast, .50 caliber-armed North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber was used, but the smaller cargo capacity limited its usefulness. On occasion, B-24 Liberator heavy bombers were employed. Several kinds of parachutes were also critical to safely airdrop supplies.

American-made “silk” (usually nylon or rayon because natural silk was scarce) parachutes performed the best. But, they were expensive and often not recoverable. At seventy dollars each—a substantial sum when a U.S. Army private during WWII made approximately $50 a month—they simply could not be used for every item. Only fragile or explosive items such as ammunition, radios, and medical supplies, were dropped using these parachutes.

Much cheaper locally-produced parachutes made of jute (burlap) were substituted to make air resupply as simple and economical as possible, especially when heavy loads required more than one parachute. Lieutenant General William J. Slim, commander of the British 14th Army, explained that since Burma was at the bottom of the priority list for just about everything, and because the world’s jute was grown in India, it was easy for the military to work with the cloth manufacturers. Within a month, they had designed a prototype parachute made entirely of jute—including the parachute lines—that proved to be “eighty-five per cent as efficient and reliable as the most elaborate parachute, at a twentieth of the cost.” Cheaper parachutes were not the only challenge. The NCAC needed to devise ways to properly pack the supplies for air-drop.