RARE! WWII "ARGYLE" Operation Boston New Guinea Campaign 8th Photo Squadron 5th Air Force Combat Map

RARE! WWII "ARGYLE" Operation Boston New Guinea Campaign 8th Photo Squadron 5th Air Force Combat Map

Comes with a hand-signed C.O.A.

This rare and museum-grade WWII Pacific Theater combat operations map was used during the infamous New Guinea Campaign (1942-1945). New Guinea was an important strategic island to both the Allied and Japanese Imperial Forces during World War II. Located east of Indonesia and just north of Australia, between the Coral Sea and the South Pacific Ocean, New Guinea is the second-largest island in the world. For the Americans, New Guinea served as a strategic point in the second stage of their offensive against the Japanese at Rabaul on the southwest Pacific Island of New Britain.

The New Guinea offensives were the single largest series of connected operations Australia and Allied forces in the Pacific have ever mounted. While the supreme command was, of course, American, and while the campaign depended upon American air and naval support, the New Guinea battles were Australia’s own. They involved tens of thousands of troops, both in combatant units and in the massive logistic infrastructure that jungle warfare demanded. From 1942 to August 1945, New Guinea was the location of some of the most infamous land, air, and naval battles in the Pacific Theater. It was here where US, Australian, British, and Netherlands soldiers fought against the Empire of Japanese. From 1942 to 1945 it is estimated that nearly 42,000 total Allied soldiers were KIA and 202,100 were KIA for Japan (127,600 on New Guinea's main island, 44,000 on Bougainville, 30,500 on New Britain, New Ireland, and the Admiralty Island).

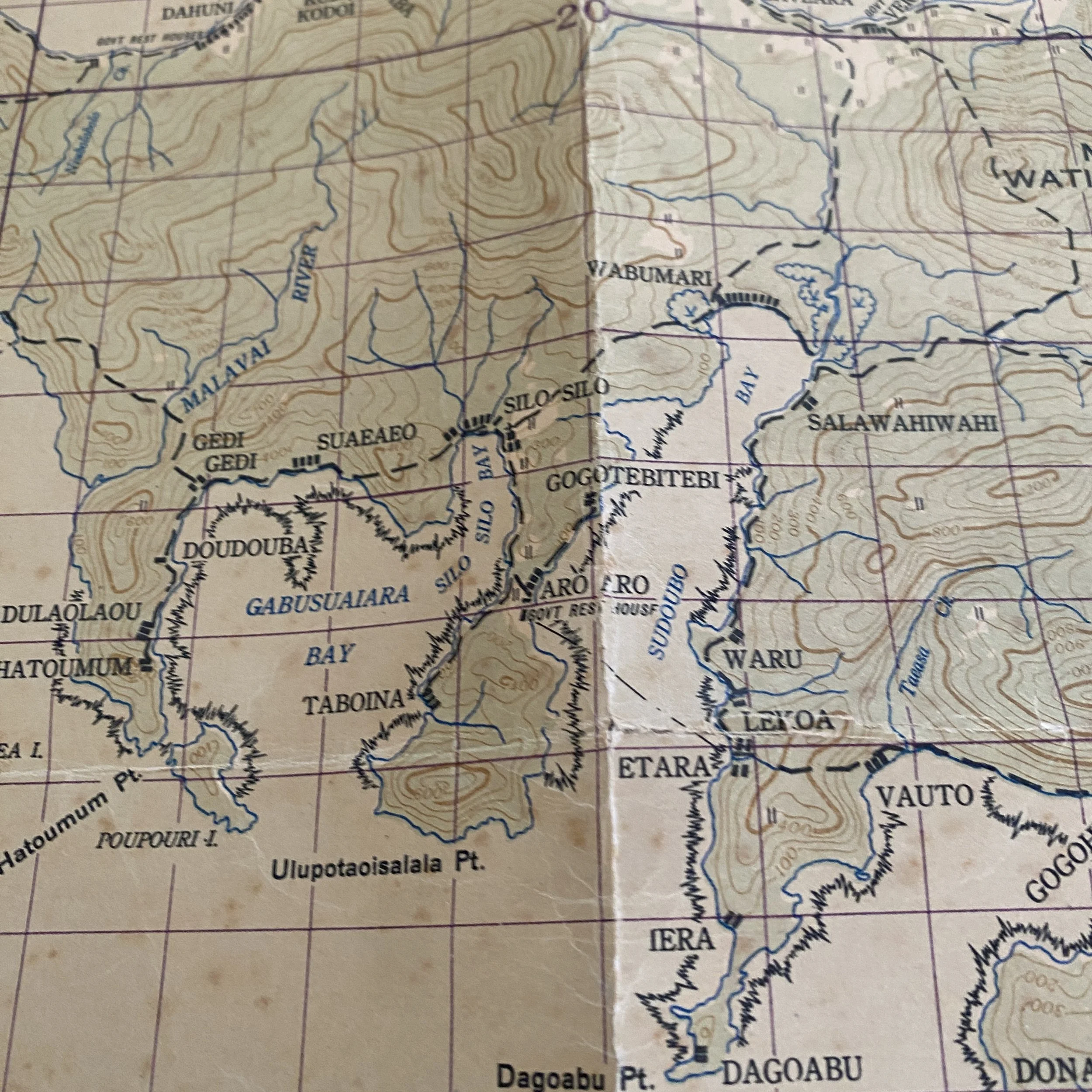

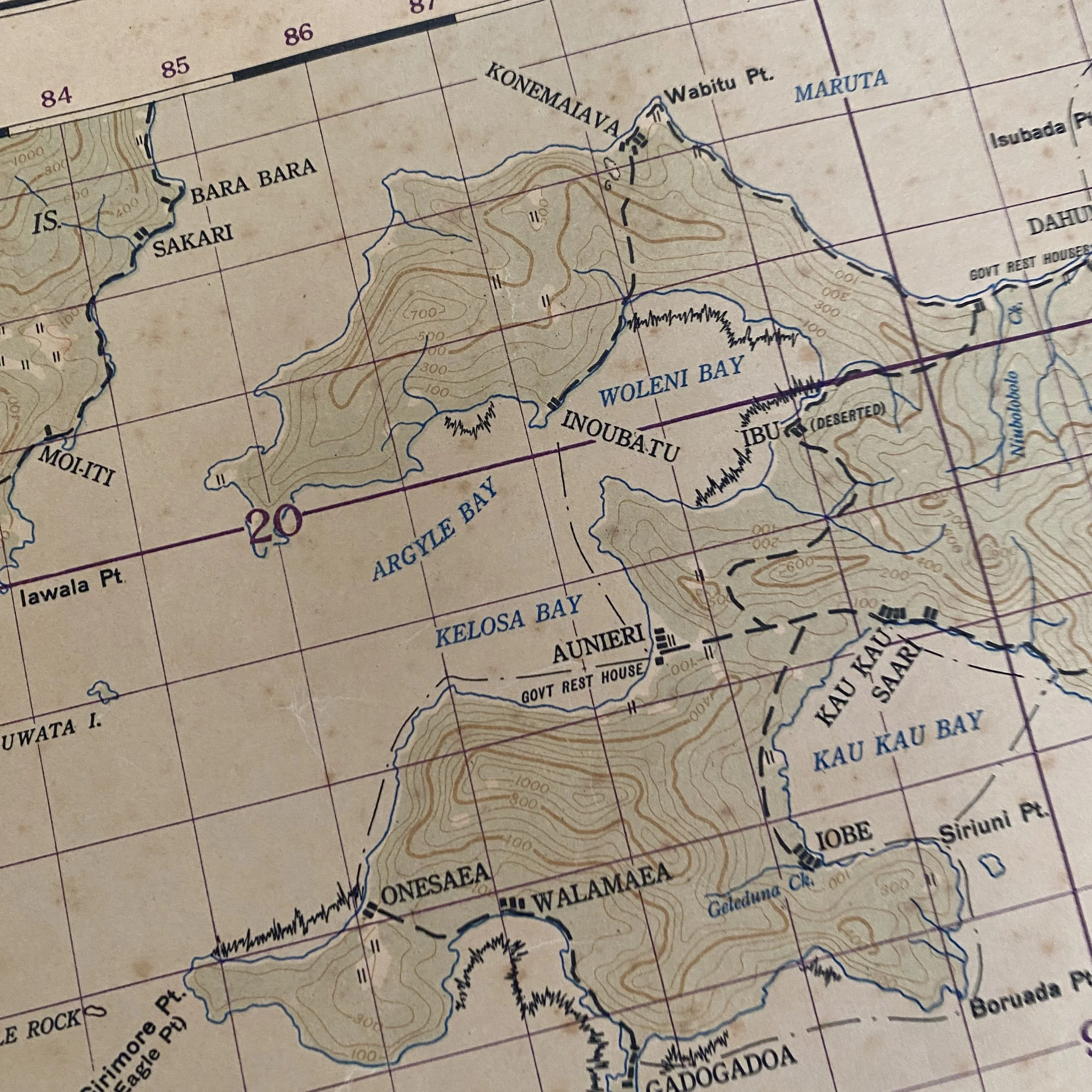

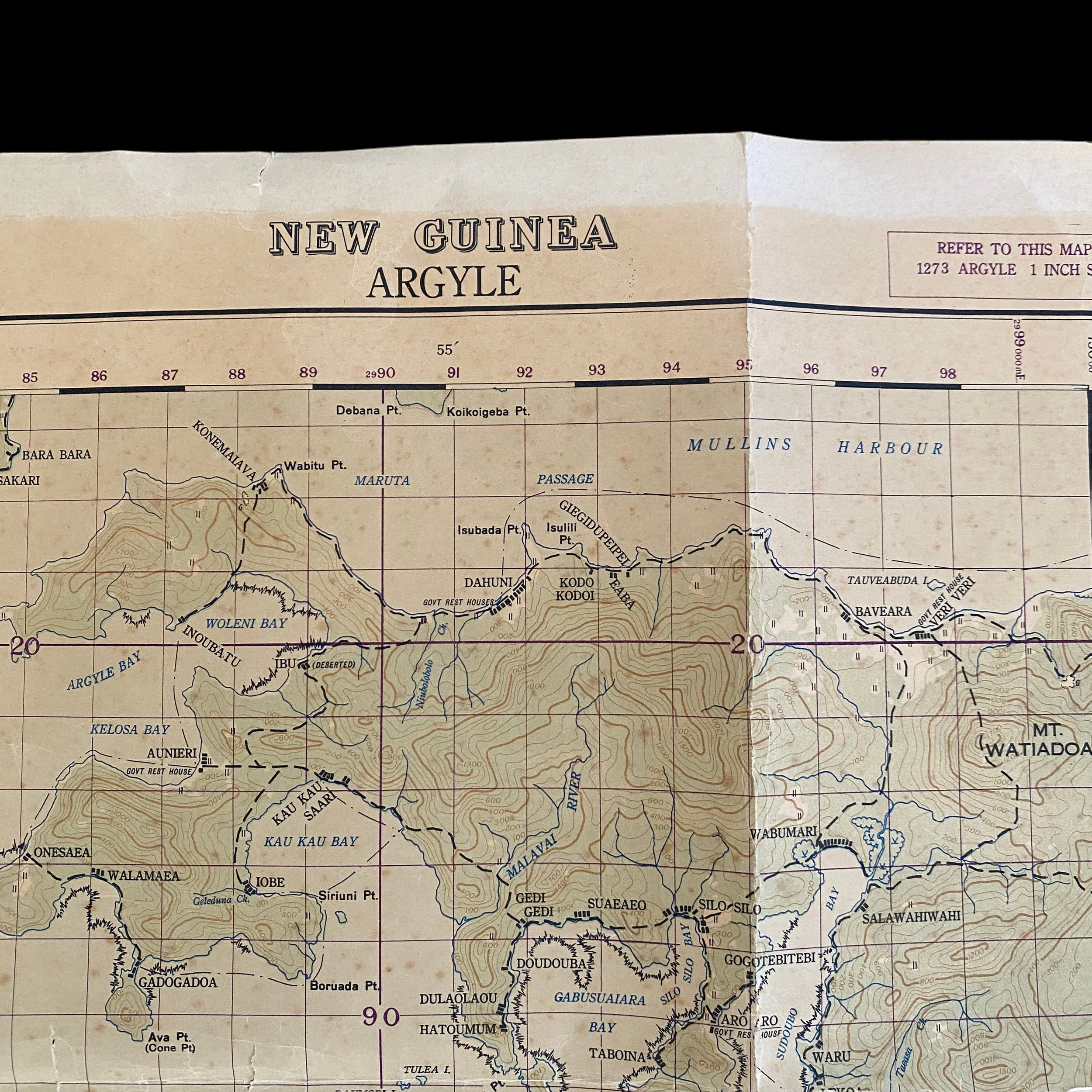

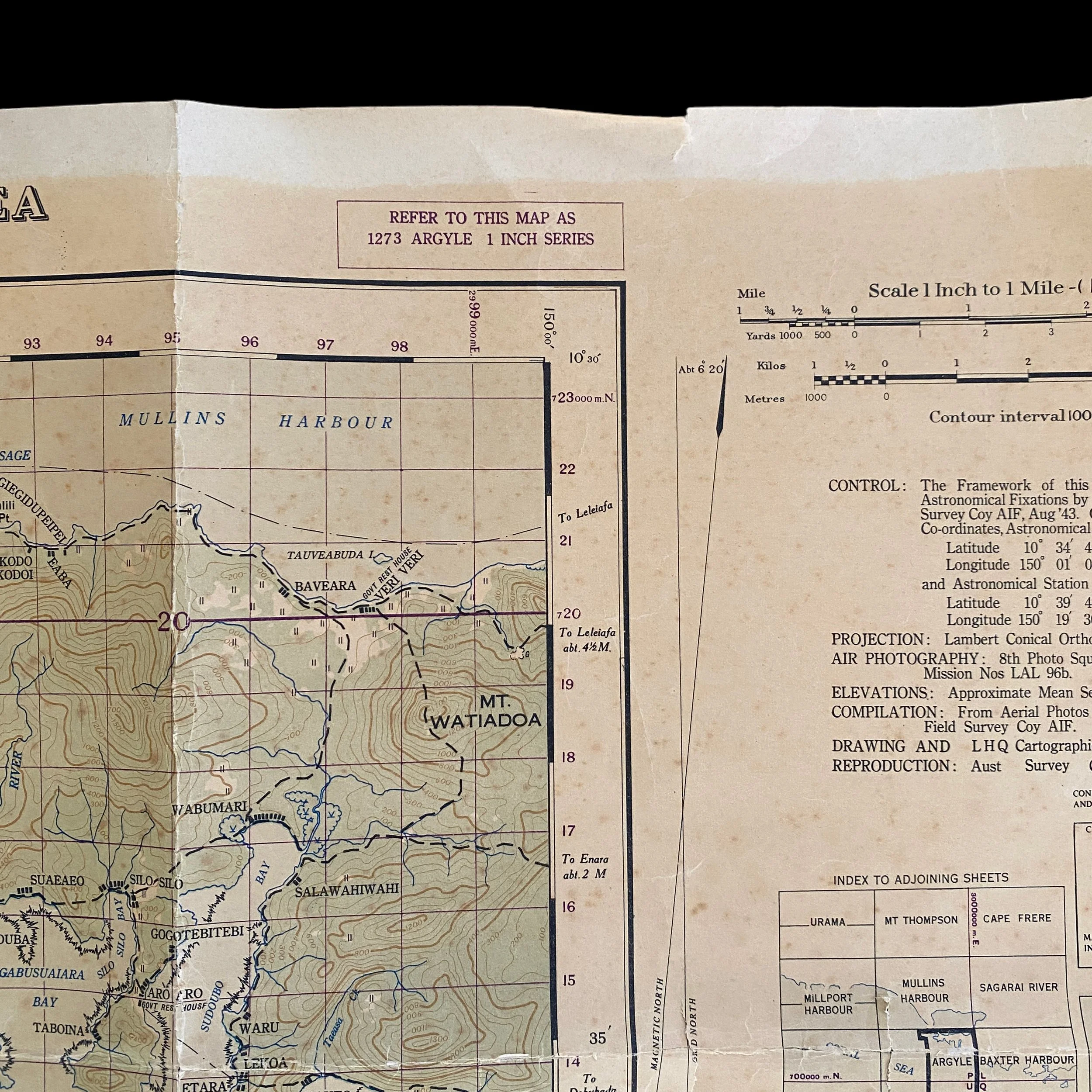

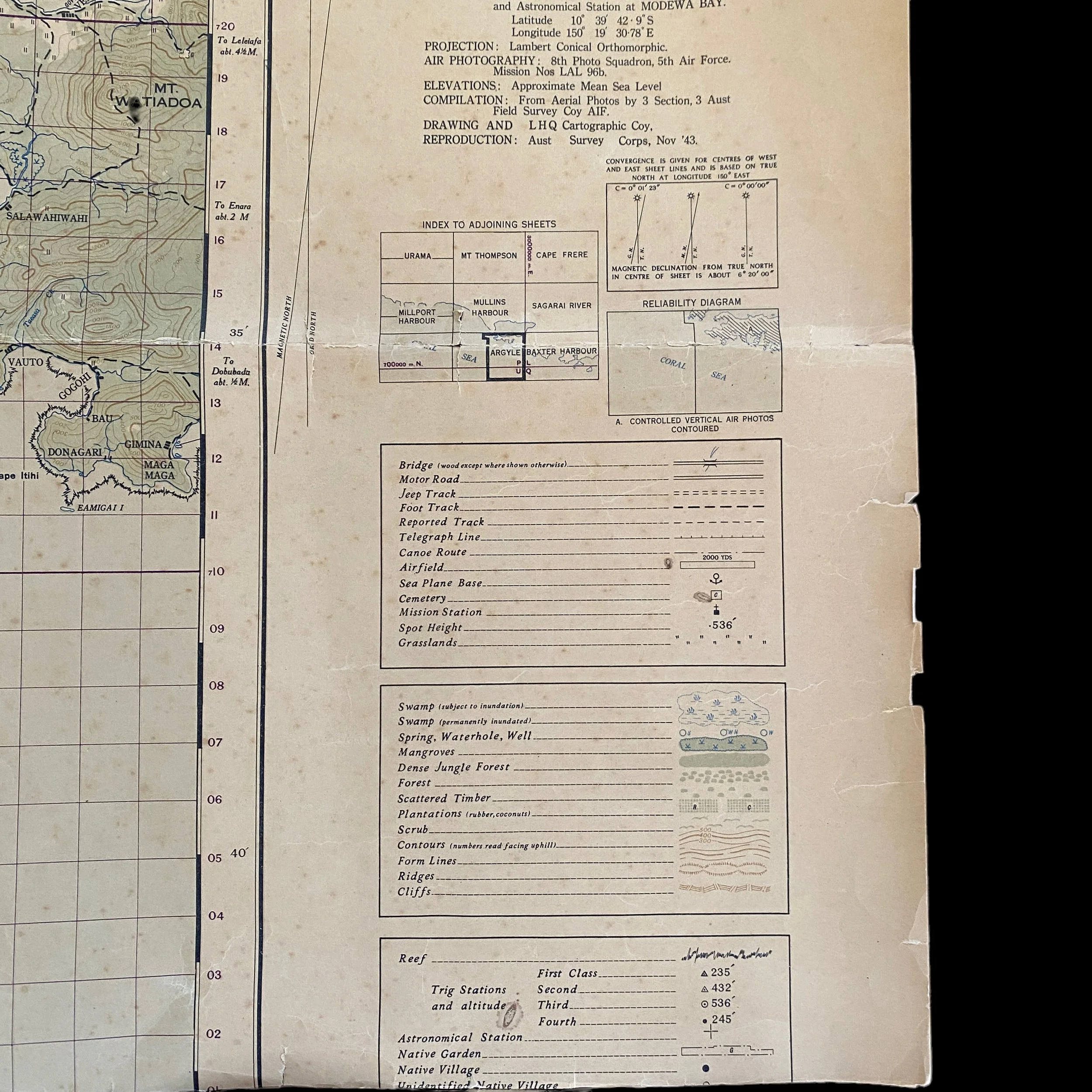

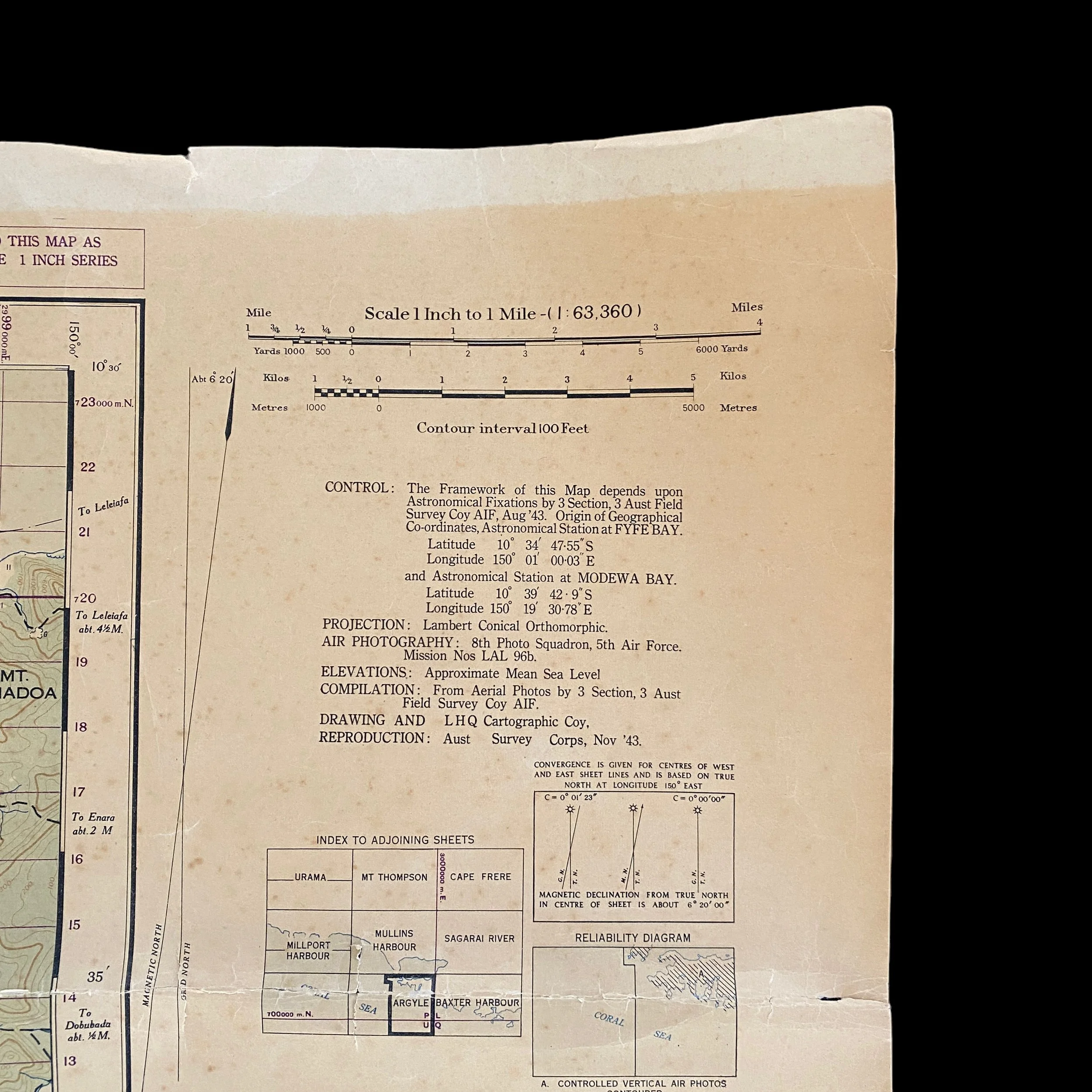

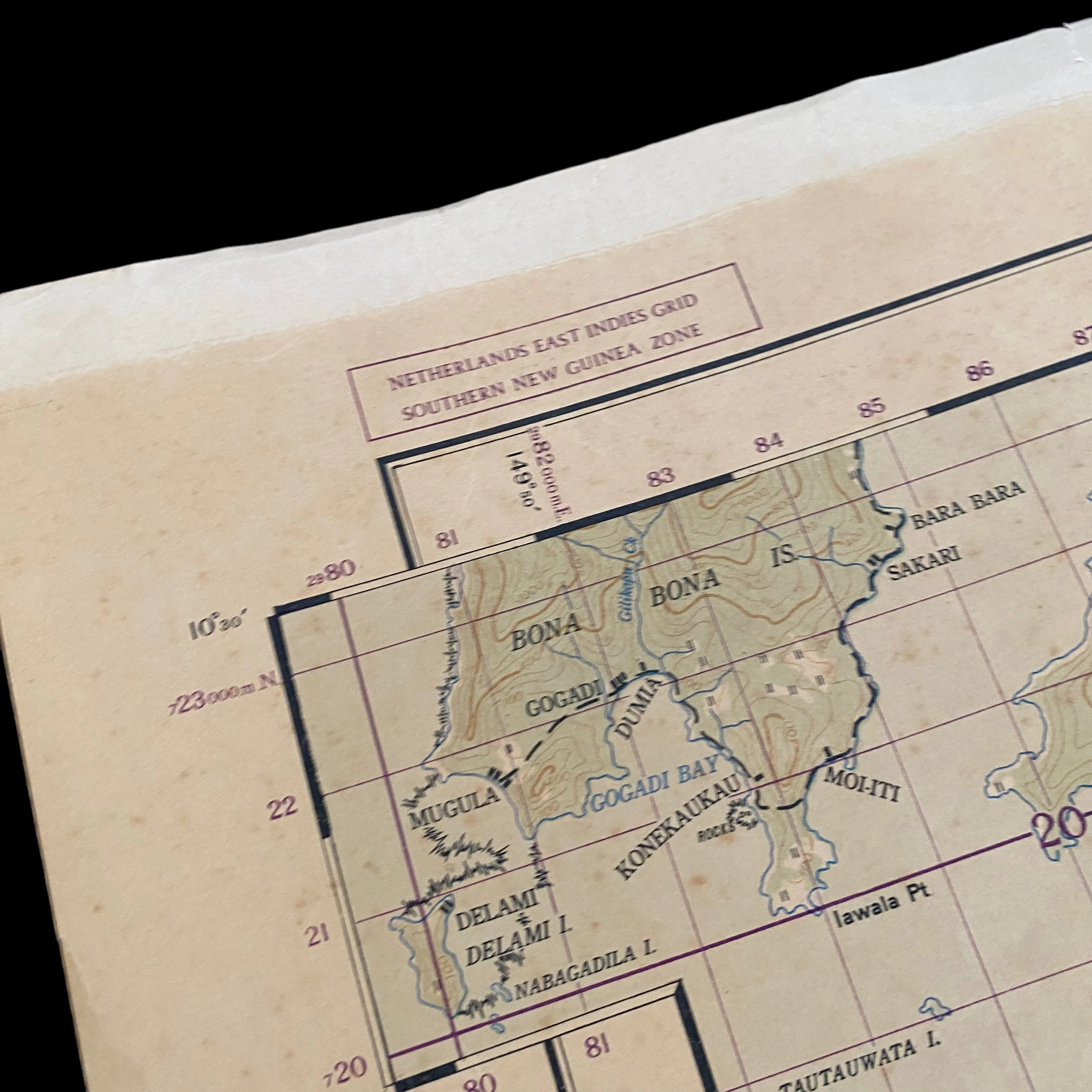

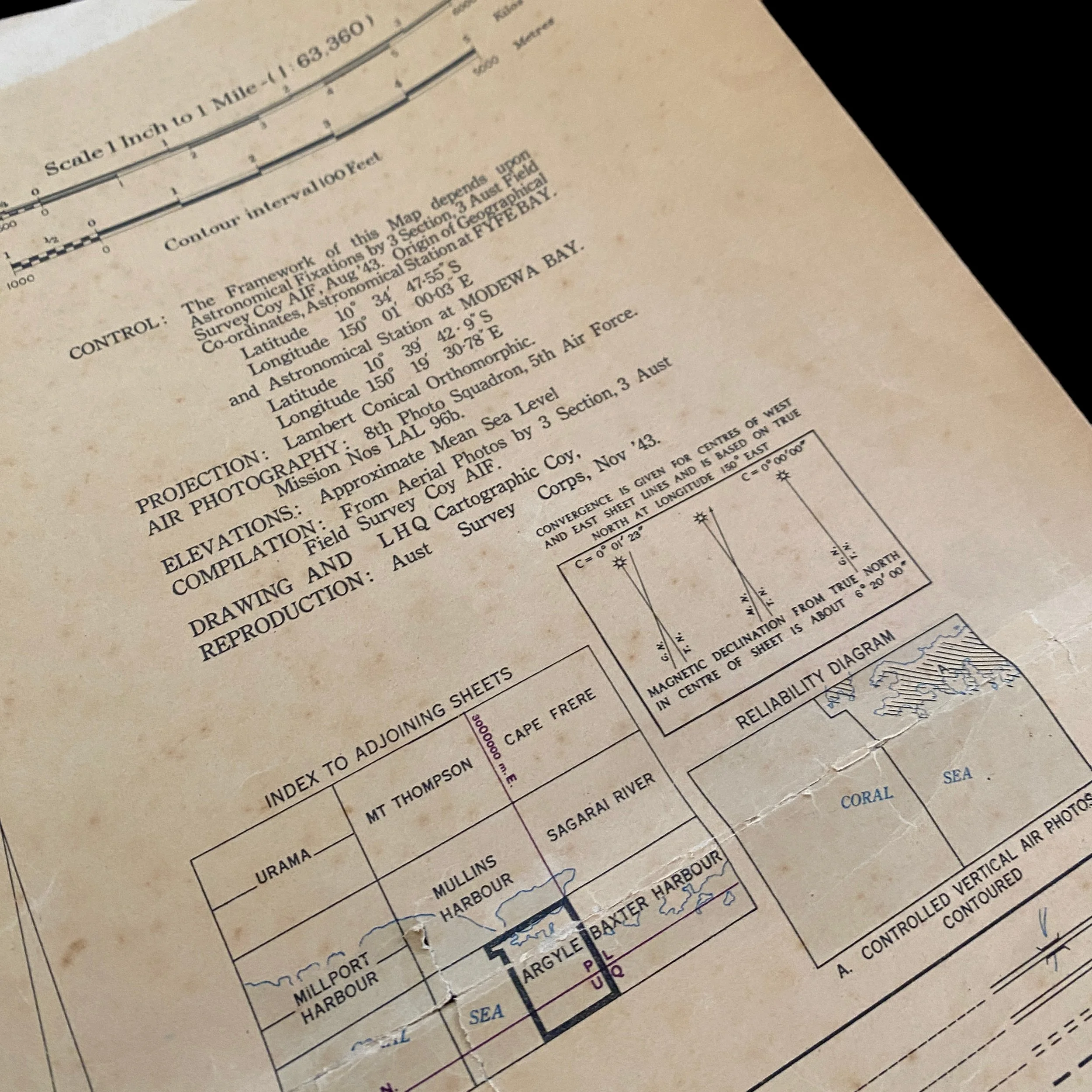

Titled “ARGYLE - NEW GUINEA” this combat map was created using aerial recon photos from the U.S. 8th Photo Squadron, 5th Air Force and shows the region near the infamous Mullins Harbour. and was used during Operation Boston.

'Operation Boston' was a US and Australian unrealized plan for the recapture of the Abau and Mullins Harbour area on the south-eastern coast of New Guinea for the construction of an airfield from which the advance of General Douglas MacArthur’s South-West Pacific Area command could be supported (20 May/11 June 1942).

The South-West Pacific Area command believed strongly that the Japanese would strike at Port Moresby with at least one infantry division and a combination of carrierborne and land-based aircraft some time soon after 10 June 1942, and MacArthur and his staff launched an immediate quest for the best means to secure the area with the forces currently available to them. These forcing were increasing. On 14 May Major General Edwin F. Herring’s US 32nd Division reached in Australia in company with the last elements of Major General Horace H. Fuller’s US 41st Division. One day later, the 3,400 men of Brigadier W. E. Smith’s Australian 14th Brigade Group began moving to Port Moresby with 700 attached Australian anti-aircraft troops.

One of the lessons of the Battle of the Coral Sea (7/8 May 1942) had been that efficient coverage of Port Moresby’s eastern approaches required the basing of Allied warplanes on or near the south-eastern tip of New Guinea. Moreover, while a base in the low-lying regions in that area would indeed shield Port Moresby’s uncovered eastern flank, it would also provide Allied warplanes with a staging post for attacks on Japanese bases to the north and north-west. Another advantage of such a base, moreover, was that its aircraft would be operating largely over the sea and/or low-lying islands, and would therefore not have to face the turbulence and other operational hazards that hampered missions over the Owen Stanley mountains. Ultimately, of course, such as base would provide a launch point for a land advance along the south-east coast.

In a letter of 14 May to General Sir Thomas Blamey, the commander-in-chief of the Australian forces, MacArthur wrote that a careful study of weather and operating conditions along the south-east coast of Papua had resulted in his decision to establish new airfields in this area for operations against Salamaua in Papua, Lae in North-East New Guinea and Rabaul on New Britain island. Noting that suitable sites appeared to be available in the coastal strip between Abau and Samarai near the south-eastern tip of Papua, MacArthur asked Blamey if he had the ground troops and anti-aircraft units with which to protect these bases. After Blamey had responded that he had the troops, on 20 May MacArthur authorised the construction of a landing strip. 50 ft (15 m) wide and 1,500 ft (460 m) long, at 'Boston', the Allied codename for the area of Abau and Mullins Harbour, which was a largely unexplored coastal area requiring an immense amount of development. The new airfield was to be constructed 'in a location susceptible of improvement later on to a heavy bombardment airdrome'.

On the same day that he authorised the construction of the 'Boston' airfield, MacArthur issued a comprehensive plan for the reinforcement of combat capabilities in north-eastern Australia and New Guinea. In this plan the air forces at Port Moresby were to bring their fighters elements up to full strength, and US anti-aircraft troops at Brisbane in Queensland were to be transferred to Townsville, Horn Island, and also to Mareeba, Cooktown and Coen, the bases along the Cape York peninsula. These bases, Port Moresby, and the new 'Boston' base were to be upgraded with full inventories of aviation supplies, bombs and ammunition so that, in the vent of an emergency, Allied warplanes would be able to use the bases, without any delays, the interdiction of any Japanese advance through the Louisiade islands group and along the south-east coast of New Guinea. The plan also demanded the acceleration of the programme to build or improve the airfields in north-eastern Australia and in New Guinea, and the transport to them of reinforcements and supplies.

When completed, the new air bases in north-eastern Australia and the York peninsula would push the basing of Allied bombers to the north by as much as 500 miles (805 km), deepening by that distance their radius of operation into Japanese-held areas. It would also bring the bombers as close to Port Moresby as was physically possible without actually basing them there, and located them well for defensive and offensive action. Moreover, the new fields and dispersal areas at Port Moresby would facilitate bomber operations staging through them to overfly the mountains for attacks on the Japanese bases in North-East New Guinea and New Britain, and would also make it possible for larger numbers of fighters and light bombers to be based there. The new 'Boston' airfield would facilitate offensive flying operations, and at the same time help to defeat any further Japanese attempt to take Port Moresby from the sea.

On 24 May the Allied Land Forces command selected the garrison forces for 'Boston', but a measure of doubt about this garrison force’s ability to hold its area of responsibility in the event of a Japanese attack, the ALF headquarters informed the garrison force that it would be responsible for ground defence only against minor Japanese attacks: if the Japanese began a major attack against 'Boston', the garrison force was to pull back, but only after ensuring that it had destroyed all the weapons, supplies and matériel that might otherwise be of use to the Japanese.

In the event the 'Boston' airfield was not built. When an aerial reconnaissance of the eastern tip of New Guinea was ordered on 22 May, it was discovered that there were better sites in the Milne Bay area. On 8 June a 12-man party of three US and nine Australians, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Leverett G. Yoder, the commander of the US 96th Engineer Battalion, left Port Moresby for Milne Bay in a Consolidated Catalina twin-engined flying boat to undertake a further reconnaissance of the area, and found a good site, suitable for several airfields, in a coconut plantation at the head of the bay. The plantation had a number of buildings, a road net, a small landing field, and several small jetties.

The importance of Yoder’s report was immediately perceived, for it offered the possibility of a base which, if properly garrisoned, could probably be held. Immediate construction was ordered as an alternative to 'Boston' airfield, whose construction was cancelled on 11 June. On the next day authorisation was given for the construction of an airfield, with the necessary dispersal strips, at the head of Milne Bay. A landing strip suitable for fighters was to be built immediately, and a large airfield for heavy bombers was to be developed at a later date.

History of the New Guinea Campaign During WWII:

New Guinea was an important strategic island to both the Allied and Japanese Imperial Forces during World War II. Located east of Indonesia and just north of Australia, between the Coral Sea and the South Pacific Ocean, New Guinea is the second largest island in the world. Prior to World War II, its eastern half, the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, was governed by Australia, while its western half was under Dutch control.

For the Americans, New Guinea served as a strategic point in the second stage of their offensive against the Japanese at Rabaul on the southwest Pacific Island of New Britain. Taken from the Australians in January 1942, Rabaul had been transformed by the Japanese into their most important defense base in the Southwest Pacific region. By the summer of 1943, about 100,000 Japanese troops were stationed there. With New Guinea in their grasp, Japanese forces could also cut communications between the US and Australia. It could also easily dominate other neighboring islands.

US troops fought alongside Australian soldiers in hopes of halting Japan’s advances in the Southwest Pacific. Teams of Military Intelligence Service (MIS) Nisei accompanied both Australian and American forces first at Buna, a major air base on the northern coast of New Guinea, and then at every battle that occurred along the island’s coasts. The Nisei linguists were at the forward area as well as at the rear, furiously translating captured documents and interrogating POWs amid grueling conditions.

The island’s jungle climate proved inhospitable to soldiers, who endured heavy rains, heat and humidity, swampy mangroves, and debilitating tropical illnesses like malaria and dengue fever as well as dysentery. With sixty pounds of gear on their backs, infantrymen trudged through the muck amidst the stifling jungle climate. An astounding number suffered from psychoneurosis and malnourishment. The thick undergrowth allowed for poor visibility, making ambushes common.

In the first year of the second stage of the campaign, from January 1943 to January 1944, the Allied forces suffered nearly 24,000 casualties, with the large majority of these, about 16,800, Australian. In the latter part of the second stage leading up to the recapture of New Guinea, battle casualties were about 9,500, mainly American.

Battles were also fought on several islands along the coast, with particularly fierce jungle warfare in western New Guinea. Roughly four MIS linguist teams, approximately 20-30 men, were shipped to New Guinea.

Just prior to his landing at Lae in September 1943, Staff Sergeant Kazuo Kozaki, one of the original graduates from the Fourth Army Intelligence School and then under the 9th Australian Division, was caught by strafing which killed more than a hundred Allied soldiers. He hit the deck but was struck on his backside. He saved one officer’s life during the incident, and endured the pain for three days before finally seeking medical treatment. For his bravery, he earned a Silver Star, the first for a Nisei soldier in World War II, and a Purple Heart.

The MIS translated a cache of documents discovered on an abandoned lifeboat off Lae, including a list of every officer in the Japanese Imperial Army assigned to a unit after October 1942. A few months after its discovery, in May 1943, the MIS was able to construct a document that gave a detailed, accurate profile of the Japanese Army. At Lae, Allied forces also captured more than 1,500 Japanese documents, enabling ATIS (Allied Translator and Interpreter Section) to compile a complete history of the Japanese garrison.

At Nassau Bay, Nisei MIS linguists accompanied both Allied and American forces in the jungle. They performed translations and interrogated POWs at the front lines. Technician Third Grade Albert Y. Tamura became the first Nisei to be awarded a Combat Infantryman’s Badge for his service under the 41st Infantry Division in September 1943.

Nisei linguists participated in the landings at Aitape and Hollandia, in the Netherlands New Guinea, beginning in April 1944. Two divisions with a Nisei team each were at Hollandia. The 41st Infantry Division had a team led by two Caucasian officers and a senior Nisei officer, Staff Sergeant John M. Tanikawa, a 42-year old World War I veteran who had been an instructor at Camp Savage. At Hollandia, the MIS Nisei translated scores of captured documents and helped as interpreters for the thousands of Japanese POWs that were kept in the prison compound constructed there. By December 1944, Hollandia had developed into a “miniature ATIS,” with nearly 50 officers and 150 enlisted.

On June 23, 1944, Technical Sergeant Yukitaka Terry Mizutari, a Hilo, Hawaii, native who led the language team with the 112th Calvary Regimental Combat Team at the landing on Arawe, took a bullet to the chest while defending his team from a surprise attack at the command post. Mizutari was the first Nisei to die in combat in the Pacific. For his bravery, he was posthumously awarded a Silver Star.

After two years of battle in New Guinea, Allied forces in both the South and Southwest Pacific were in position for a final assault on Rabaul. Instead of a direct attack on Rabaul, Allied forces encircled the area in a plan that was codenamed “Operation Cartwheel.” They secured other islands along the Admiralty Islands located north of New Britain Island and New Guinea, thus isolating Rabaul. As a result, thousands of Japanese troops were cut off, as were communications and supply lines. The offensive against Rabaul was complete.